Discussed in this essay:

Manhattan Beach, by Jennifer Egan. Scribner. 448 pages. $28.

It’s always tempting, but almost never fun, to try to see what one looks like from the outside. There’s a glimpse of an American future near the end of Jennifer Egan’s fuguelike novel A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010), and it’s looking pretty bleak. We don’t know quite what year it is, but time has passed, lives have been lived, and disappointments have been swallowed. The air is darkening as ever higher skyscrapers rise all around and surveillance helicopters drone overhead. Communication, even between those in the same room, now feels easier via device, in an increasingly truncated textspeak that has begun to infect thought as well. Entertainment must be calibrated to appeal to the broadest spectrum possible, especially to very small children, of whom there are an inordinate number because, as a parent thinks to himself, “if thr r children, thr mst b a fUtr, rt?” None of this would make perfect sense as a prediction, but like many depressing fantasies of the future, by turning up the dial on some of the sadder, pettier, more undignified aspects of the present, it does have a certain power to make us uncomfortable.

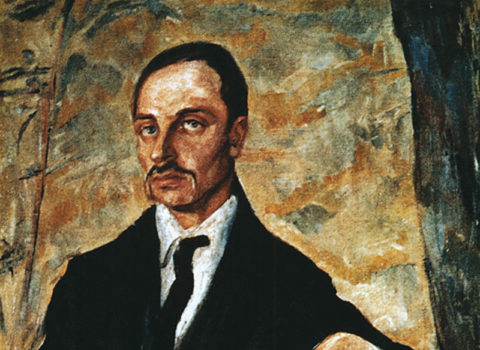

“Speed Graphic View Camera, circa 1940,” by Susan Dobson. Courtesy the artist and Michael Gibson Gallery, London, Ontario

Most of Goon Squad takes place in the recentish past, yet gives the same slightly unsettling sense of peering in from elsewhere at what should be people like yourself — the effect is akin to seeing old photographs or rereading an ancient diary and thinking, What happened? Did I really feel that way about it? Time is the “goon” of the title — or Egan herself is, exploding a whole bunch of imaginary lives into little scenes and fragments and then letting us piece them back together haltingly and imperfectly. Many characters are only sketched in, and the narrative skips back and forth in time and among people, full of abrupt switches and lacunae. The years lost to a drug addiction go by in a sentence or two; several marriages and their acrimonious ends are dealt with in a paragraph; and ambitious, promiscuous young sellouts are suddenly gone-to-seed nostalgists struggling to regain the occasional hard-on. The characters themselves aren’t given much room to marvel over these turns and transformations, but there are exceptions, as when a down-on-his-luck janitor visits an old friend, now a swanky record exec, to ask, “What happened between A and B?” “A is when we were both in the band, chasing the same girl,” he reminds the exec. “B is now.” (Silently, he translates the question: “We were both a couple of asswipes, and now only I’m an asswipe: why?”)

The central brilliance of Goon Squad is its cheeky ability to turn what could have been weaknesses into strengths. It’s a trick Egan manages through her mastery of rhythm, which is to say by echo and repetition and by leaving out most of what lies between A and B — and, of course, Z. Set amid the music industry’s 1970s heyday and decline, the book includes an analysis of the uses of the pause in pop songs. Like an album, the novel is structured by its own artful pauses, which provide leeway for the expressions of heightened feeling in between. What might seem sentimental becomes an insight into the workings of people’s sentiment; figures who could be mere stereotypes become real, self-conscious creatures striving to live up to those stereotypes, or simply souls whose more complicated interior worlds, like everyone’s, are hidden from those around them; what might have been a lazy wrapping-up of a plot strand becomes a vivid evocation of how people affect us and then vanish, the rest of their stories permanently obscured. In other words, what is cheap grows resonant, what is absent becomes something to savor. The gaps and sudden metamorphoses can in themselves produce a startling effect of reality — the more paltry and cliché the frustrated hopes, the more recognizable they seem. The book offers a formal rendering of themes Egan has been drawn to throughout her career: the performance of the self; a prenostalgic longing for some more authentic experience; a chronological claustrophobia in which the American promise of a wide-open vista of possible lives is always already broken.

Egan’s new book, Manhattan Beach, plays things much straighter, at least on the surface. A historical novel beginning during the Depression, it soon becomes a wartime romance, albeit one between a woman and the deep blue sea. Anna Kerrigan, its restless Irish-American heroine, longs to join the war effort as a diver repairing Navy ships, a job that’s strictly reserved for men. Growing up poor with her severely disabled sister, Lydia, Anna was used to being taken along on her father’s shady work assignments, but before long, Eddie Kerrigan has vanished, perhaps killed, and Anna joins a phalanx of young women measuring battleship parts in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The story is narrated in a close third person that inhabits a handful of characters: we mostly follow Anna, but also look in on Eddie in his younger days and on one of his associates, Dexter Styles, an Italian-American nightclub owner who Anna suspects may know something about her father’s disappearance. For the most part, time moves only in the expected directions: there’s the odd dreamy flashback or a journey into someone’s childhood to fill in how he got here, but unlike in Goon Squad, there are no midsentence fast-forwards into the future, no compressing of decades and lives into paragraphs or skipping back to catch a glimpse of the same people from a surprising angle. As in a period film, events follow a graceful track and, wherever the camera turns, everybody looks just right.

Egan has always been intrigued by how what we look like constrains who we are — quite a few of her previous characters recall those Sopranos mafiosi eagerly taking tips from The Godfather. The mobsters in Manhattan Beach are full of motivations that, if not always appealing, are reliably picturesque. The aptly named Styles punishes an underling to demonstrate his supremacy, but also because the underling has insulted a woman. (Styles’s respect for women is a bit of a theme.) His father-in-law, a banker smilingly predicting a victory in the war followed by the rise of American hegemony, has made sure to insist, as a condition for his approval of their marriage, that Styles be impeccably faithful to his daughter. The men who run things, both the explicitly criminal and the supposedly legitimate (who are, naturally, aware that they’re symbiotic parts of a system), operate according to a strict honor code that we already understand — their loyalties and sensibilities can be precisely and elegantly traced. In the third person, though, it’s not always clear how unfiltered the thoughts we hear are supposed to be, or whether what we see is only the face these men want to show one another.

Egan’s preoccupation with faces, with seeing and being seen and the intricate network of traps that both involve, goes back a long way. Even the two epigraphs to her first novel, The Invisible Circus, embody what she presents as a central American tension: Ludwig Feuerbach’s diagnosis of the present as an age in which only illusion is sacred, Emily Dickinson’s image of bursting through the illusory everyday (“Exultation is the going / Of an inland soul to sea, / Past the houses — past the headlands — / Into deep eternity —”). In Egan’s short stories, people are always anxiously observing themselves and their lives at a remove. “Someday I’ll know I was lucky to be here,” a girl thinks; a striving young man observes that New York City is “a place that glittered from a distance even when you reached it.” Egan is drawn to characters whose jobs and circumstances make them emblematic of an age both hypermaterialistic and bafflingly dematerialized. There are con men and fashion models and stylists and P.R. gurus and disgraced financiers and demographic consultants and a man who photographs food for a living, using Elmer’s glue instead of milk to get the seductive whiter-than-white that will spark viewers’ desire. (Foreigners note with awe and resentment the whiteness of American milk and the orangeness of American oranges.)

Egan’s best book is perhaps Look at Me (2001), though that novel can’t quite sustain the intensity of its convictions all the way to the end. It offers the most explicit treatment of these problems, and shows her satirical and humanistic impulses at their most finely balanced. The novel follows a model, her career already in decline, whose face is radically altered in a car crash and who is offered a series of compromised redemptions (meaning: ways to regain the public’s attention). She is joined by a college hero who becomes a lone crank railing against the information age and a would-be terrorist making his home amid the McDonald’s and TV and other comforts that once signaled defeat to him. Egan’s work performs a historically specific balancing act: so many of her people are either fakers or stuck in surroundings that feel fake (or both), and still we must believe in them and their struggles enough to lend the story its propulsion and emotional heft. The interactions among her characters frequently offer the reader the shock of the real, and yet this is in part because they exist as if trapped behind glass — a feeling we recognize as drawn from life.

Anna Kerrigan is an odd hybrid. On the one hand, she is the most recognizable kind of period-piece heroine, combining old-fashioned virtues like pluck and singlemindedness and loyalty with those a more modern girl must display lest she seem too much of a prig. On the other hand, she’s an ambiguous trickster, always subtly shifting and lying her way out of trouble. There are suggestions that the attraction to the sea she shares with both her father and Styles goes along with a slippery, changeable quality: just as Eddie is valued by his bosses for his ability to move in and out of different spaces and social contexts without being noticed (especially useful when ferrying bribes between people who’d rather remain apparently unconnected), she’s someone who can fit in when necessary, deflect attention, talk her way around any problem. “You could be a spy or a detective,” Nell, her Betty Grable–type girlfriend at the Navy Yard, says. “No one would know who you really are or who you work for.” This skill extends to physical dexterity: we hear in several contexts about the feats Anna can perform with her hands, eyes closed.

It’s often in the moments when she does this that the novel’s relationship with time begins to seem more complicated — she feels it slip and slow and speed around her. There are passages in which the mechanics of plot and even character appear to slide by in a familiar lull while the real life of the book goes on elsewhere, in little explosions of the sensual. (In this respect, it’s not unlike Goon Squad, so much of which takes place between the lines.) Even as a child, Anna experiences lives within lives: moving between the worlds of home and her father’s work, she feels she has “shaken free of one life for a deeper one,” forgetting each in turn “until it seemed there was no place further down she could go. . . . She had never reached the bottom.” In a way, it’s the experience of someone who doesn’t very often need to lie but can simply navigate a situation according to its requirements, untroubled by the reality of the past year or even the past five minutes.

Manhattan Beach is clearly lovingly researched, and Egan has folded in pieces of real stories — for which several people are thanked in the acknowledgments. But despite the sparing delicacy with which she uses period detail, the heart of the novel lies elsewhere. The book is most centrally concerned with a particular feeling, one frequently evoked in Goon Squad too: an almost erotic yearning to transcend limits, to escape oneself.

The sea is the focus of much of this yearning, but it also appears in other places. A heightened and aestheticized physicality runs throughout the book, with some sharp beauty or swooning pleasure evoked on every page. Borrowing a bicycle from Nell on her lunch break, Anna finds she can fly:

Motion performed alchemy on her surroundings, transforming them from the disjointed array of scenes into a symphonic machine she could soar through invisibly as a seagull. She rode wildly, half laughing, the sooty wind filling her mouth.

The first test Anna is given by the divers, on the assumption that she’ll fail and then can be easily fobbed off, is to untie an elaborate knot while weighted down by two hundred pounds of equipment. The description of her finding a vulnerable point is tinged with eroticism, which helps make time go slow-quick-quick-slow:

She felt the knot’s weakness, like the faint, incipient bruise on an apple, and dug her fingers in. . . . The knot made a last clutching effort to preserve itself, its reluctance to yield making it seem almost alive. Then it surrendered, the cords loose in her hands.

Most striking of all is the languor and gorgeousness associated with Lydia, the sister who can’t stand or talk, and whose murmurings also seem to connect her to the sea: “Anna danced holding Lydia until her sister’s floppiness became part of the dancing. All of them grew flushed; their mother’s hair fell loose, and her dress came unbuttoned at the top.” The experience of bathing Lydia has none of the sadness and difficulty one might expect — it is otherworldly. As they lift her out of the water, there are “bubbles gleaming on the unexpected twists of her body — beautiful in its strange way, like the inside of an ear.”

For this elemental quality, it helps that Egan has chosen World War II, a period in which normal social rules were more or less suspended: identities can be shed more easily, and even nice girls can get away with far more than they could before (or after). It’s also a period visually and aurally familiar to us, layered with previous versions of itself, which adds to the undertow of sensuous unreality. (At one point Anna watches some young couples clutching each other as “I’ve Heard That Song Before” plays.) There’s a light, foamy gratification to be found in every detail.

By the same token, the stakes feel oddly low. You sense that everything will work out well, or at least neatly, prettily. Even the pains and disadvantages of womanhood, though they come up a good deal, don’t seem to affect Anna — they become almost part of a backdrop of comical old-world charm. (The same is true of race: the evocation of the experience of Marle, a black diver, for instance, is notable for its gentleness.) Rose, a married friend at the yard, warns Anna that the other girls are beginning to talk about the special treatment she is getting from their supervisor: “A reputation lasts. . . . It follows you.” In the world of the novel, this kind of warning turns out to be just true enough to spark a bit of mild drama, and yet nothing and no one really puts up much of a fight against Anna. The dive boss comes around so thoroughly that he forgets he ever doubted her; in fact, she captivates most of the men she meets, and she gets what she wants without having to sleep with any of them. The sex she does occasionally have is, despite the prevailing cultural assumptions, charmingly egalitarian.

It’s not just Anna — at least one other character escapes what seems certain death not once but twice — and yet she’s the figurehead, at times more like a force than a person. “Loosening a knot,” she thinks during her test, “always seemed impossible until it was inevitable,” and that’s how most things go for her. Anna longs to show her sister the “strange, violent, beautiful sea” that “touched every part of the world, a glittering curtain drawn across a mystery.” Egan expertly evokes the longing for something mysterious, and yet never quite wants to make it happen. There’s more beauty here than strangeness, and the violence never bursts its bounds. An unmistakable smoothness is given to what could have been rougher and more frightening, on or off land. The past is not so much a foreign country as a movie set. You slide into bright waters, but there’s no danger of getting hurt, no chance of drowning.

While all this could sound like a failure of imagination or ambition on the part of the author, it strikes me, in the end, as something rather eerier. Stripping away a layer of anxious generational irony, Manhattan Beach only hints at the conflicts that animate Goon Squad and are the explicit subject of Look at Me. Egan’s powers of microscopic social and psychological observation here occupy the foreground, and her critique of postwar American culture is turned down to a whisper — readers who start with this book could be forgiven for missing it altogether.

All her previous work has contended with recent society as shaped by American power, which, both crude and insidious, continually co-opts and exhausts any creative energies in its path. By contrast, the imagined world of the new novel feels oddly frictionless. As an analyst of the shallows, Egan must always gesture toward depths that she imagines might have been reachable before. But it feels too late for her — or for us — to escape into them. Both Goon Squad and Look at Me end with a quick leap forward in time, a jump that forces the reader to look back from a dystopian future that feels naggingly like the moment we now live in. In Manhattan Beach, Egan doesn’t describe it again — she doesn’t need to. That future is where we’re reading from, and every aspect of this novel (so well disguised as retro-futuristic) is marked by it.