When last we heard from Isabel Archer, she was on her way from London back to Rome, where her husband, the cruel, cosmopolitan aesthete Gilbert Osmond, was waiting. That’s how Henry James wrote it, anyway. Recall, if you will, the outline of The Portrait of a Lady: a spirited young woman from Albany, New York, arrives in England, inherits sixty thousand pounds, rejects two suitors, and, catastrophically, marries a third. In short order, Isabel, who had possessed “a certain nobleness of imagination” and whose ideal had been “the free exploration of life,” is ground down in “the house of suffocation.” The big reveal comes when she discovers that her stepdaughter is the love child of her husband and the blond Brooklynite Serena Merle, who together concocted the scheme to trick the wealthy naïf into matrimony. In the final pages of the book, a shattered Isabel defies her husband’s command and journeys to England to attend the funeral of her beloved cousin. On the eve of her return to Italy, she is clear-eyed about the suffering that lies in store. “It won’t be the scene of a moment,” she explains, “it will be a scene of the rest of my life.”

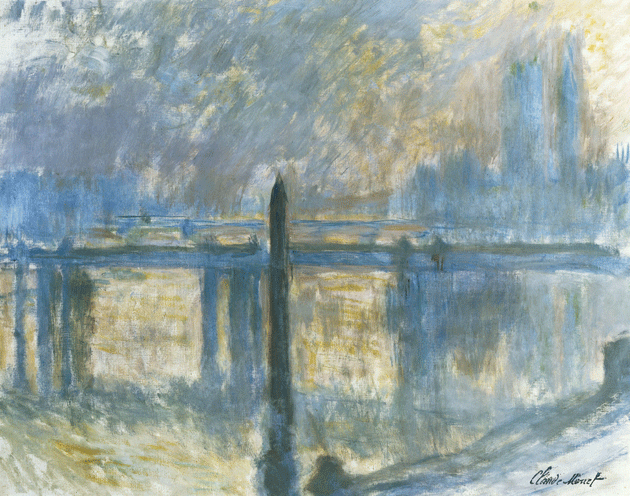

Cleopatra’s Needle and Charing Cross Bridge, by Claude Monet © Private Collection/Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

“The obvious criticism of course will be that it is not finished,” James wrote in his notebook in 1881, “that I have not seen the heroine to the end of her situation — that I have left her en l’air.” In fact, some reviewers of the first edition wrongly concluded that Isabel had left Osmond for the passionate industrialist Caspar Goodwood, and accused James of immorality and worse. “A lamer conclusion to a brilliantly written story could ill be concocted,” was The Dial’s verdict. James added a paragraph to the 1908 New York Edition that ought to have cleared up any lingering doubts, but for those who can’t stop wondering what if or keep themselves from screaming, like some deranged moviegoer, “Don’t go back inside the house!” John Banville has written MRS. OSMOND (Knopf, $27.95), a sequel that picks up the day James’s novel closes. Ours is a televisual age, after all, when every good story gets renewed for a second season.

After more than a dozen novels — he won the Man Booker in 2005, for The Sea — perhaps Banville is tired of coming up with new characters. A few years ago, in the crime-fiction guise of Benjamin Black, he published a Philip Marlowe mystery (with the blessing of the Chandler estate). Now he is doing his best impression of James. Banville is an expert stylist, and his talent for ventriloquism comes as no surprise, least of all to him. Mrs. Osmond is not “as intricate as James,” he admitted in an interview, “but if you were to look at it superficially, you could mistake it for James.” This is true as far as it goes. Mrs. Osmond is stuffed with high-octane vocabulary, winding sentences, extended metaphors, and calm, assured free-indirect passages. “Her aunt was looking at Isabel now with an expression of large surmise, in the fashion of one suddenly seeing craft and cunning where before there had seemed dullness only”: the use of “large” is very Jamesian. There is even a visit from the master himself, who shows up in a pince-nez and a blue-and-yellow waistcoat. (“Did he know her, had they met at some time, somewhere?”) But Mrs. Osmond does not expand our sense of the original. It is highbrow fan fiction, and does at once too much and too little with the source material.

We learn, for example, that Osmond did not just happen to benefit from the first Mrs. Osmond’s convenient expiration; he put her in death’s way by taking her, when she was already ill, to a plague-ridden city. Such surplus villainy is cartoonish — Osmond was bad enough without being a wife murderer — but helps justify Isabel’s decision to leave him. Banville also has Isabel grapple with the responsibility of her wealth, though in a hammy way, by agonizing over not having given money to a beggar at Paddington station. I think he is trying to show that she has learned to be more human, but as a moral awakening it’s more Dickensian than Jamesian.

The overriding reason Mrs. Osmond fails is that Banville sidesteps the questions that worry the readers of Portrait. The problem of James’s ending is not that we don’t know what Isabel does — it’s that we must answer why. Why is it that she, as James has it, “can’t escape unhappiness”? For what end, or for whom, is she living? What meaning can she wring from her disillusionment? Banville waves a wand and these questions vanish. His is a rescue mission, not a literary one. (You might as well show up in Jude the Obscure and start passing out contraceptives.) He has the sense not to marry Isabel off to someone else, but doesn’t know what to do with her. James gave Isabel’s life an arc and a destiny, however tragic. Banville restores her to the condition in which we first met her: a single, uncommitted heiress who wants to be free. But freedom, as Portrait shows, is hardly an end in itself.

Mrs. Osmond is not the only novel to be published this month about a woman who couples up with a monster. O happy day, the reissue of Rachel Ingalls’s MRS. CALIBAN (New Directions, $13.95)! Thirty-five years old, it is fresher than most things written yesterday. I wish I could say that I have always known about it. Instead I confess to the zeal of a new convert. Every one of its 128 pages is perfect, original, and arresting. Clear a Saturday, please, and read it in a single sitting.

Dorothy is a housewife. Years ago her son died during a routine appendectomy. Her next pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. Then the dog died. Her husband, Fred, had an affair; he broke it off, but now she suspects he is taking up with someone new. For the past three weeks, she’s been getting messages from voices on the radio that only she can hear. They tell her that she’ll have another baby, or report on unlikely subjects, such as a violin-playing chicken (“the Heifetz of the hen-coops”). On the day Mrs. Caliban begins, Dorothy hears a program about Aquarius the Monsterman, who has escaped from the Jefferson Institute for Oceanographic Research. Guess who turns up, seeking refuge, in her kitchen?

“Roman Forum, Rome, Italy” © colaimages/Alamy Stock Photo

The frog-man’s eyes are large and dark. His hands and feet are webbed. He stands six foot seven and has a bulbous but not unappealing head. Call me Larry, he says. (He speaks English with a “bit of a foreign accent.”) Dorothy hides him in the spare room. Under cover of darkness, she and Larry take drives, explore the neighborhood, and go to the beach. They talk about the torture he suffered at the institute and compare notes re: life on land versus life in the ocean. Their mutual attraction is strong and immediate. They do it on the living room floor, the dining room sofa, the kitchen chairs, and in the bathtub. Also on the beach. Also on the bed. Dorothy’s husband doesn’t understand why she is buying so many avocados (Larry’s favorite).

Ingalls’s narrative is a miracle of economy and grace. (Most of her books are novellas, which might explain her obscurity.) She writes straightforwardly, without winking, dropping only occasional hints that Dorothy’s tether on reality might be frayed. When Dorothy’s aquatic paramour worries that any child of theirs would be labeled a monster, for example, she gives this head-scratching response: “Born on American soil to an American mother — such a child could become President.” Larry’s connection to Caliban is clear enough — he is a frightening other to be feared, enslaved, and, when that fails, exterminated. As a romance, the book is tender; as a portrait of depression, exquisite and tragic. Dorothy can’t swim against the tides of grief and melancholia. Does Larry really exist? “This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine” is not a statement that Mrs. Caliban ever utters.

“This was the noblest Roman of them all,” declares Antony over Brutus’ dead body in the last scene of Julius Caesar:

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mixed in him that Nature might stand up

And say to all the world “This was a man!”

As Kathryn Tempest reminds us in BRUTUS: THE NOBLE CONSPIRATOR (Yale University Press, $28.50), the historical Antony is unlikely to have made any such remarks; yet there was, in Marcus Brutus’ lifetime and among the ancient commentators, a widespread belief that the liberator was “an honorable man.” The most famous assassin of the dictator perpetuo was a student of philosophy who acted, it was said, not out of personal greed but out of concern for the republic. He was the descendant on his father’s side (or so he claimed) of Lucius Brutus, who had driven the last king out of Rome, and, on his mother’s side, of Servilius Ahala, who in 439 b.c. killed the would-be autocrat Spurius Maelius. It was this lineage that inspired the graffitists of 44 b.c. Someone inked utinam viveres (“If only you were alive”) beneath the statue of Lucius Brutus. The praetorian tribunal where Marcus Brutus worked was also tagged. brutus, are you asleep, you’re no brutus. Etc.

“Avocados, 1936,” from the monograph Paul Outerbridge, by Manfred Heiting and Elaine Dines-Cox, published by TASCHEN. Photograph by Paul Outerbridge Jr. © 2017 G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, Beverly Hills, California

The people of Rome may have clamored for “another Brutus” and resented Caesar’s monarchical aspirations, but unlike the elites, who studied Greek philosophy, they did not think the imperator was a tyrant and did not go in for tyrannicide. It proved easy to kill Caesar, and impossible to kill Caesarism. Life in Rome got worse after the assassination (a bloody civil war culminated in the triumph of Augustus, né Octavian, the first Roman emperor), but did Brutus deserve the punishment concocted by Dante — to be mashed in the teeth of Lucifer alongside fellow conspirator Cassius and brother-in-treachery Judas Iscariot in the lowest circle of Hell? It depends on your source. Shakespeare was influenced by Plutarch, who held up Brutus as an exemplar of virtue; Dante read Lucan, Appian, and Virgil, who hailed Octavian as “the young champion” and the rescuer of “a generation turned upside down.” But it is Cicero who had the greatest influence on Brutus’ reputation, causing generations to view him as a brave idealist who forgot to make a plan for what would happen on March 16.

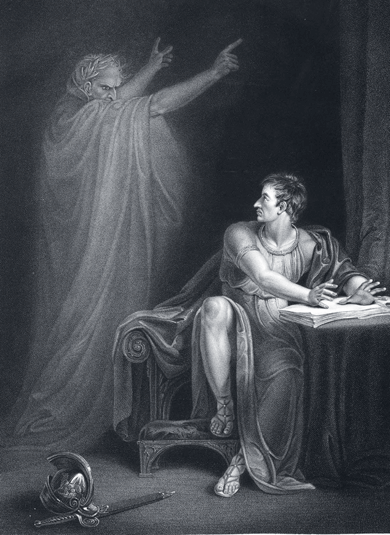

Brutus and the Ghost of Caesar © British Library Board/Bridgeman Images

“By all means, we must fly. But with our hands, not our feet,” Brutus is reported to have said before committing suicide after the second battle of Philippi. Death scenes were of special importance to the Romans. In Suetonius’ account of Caesar’s assassination, the ruler dies with only a groan, emphasizing the surprise nature of the attack. His famous last words — Kai su, teknon (“Even you, my child”) — may have been concocted by Brutus’ detractors, who started the rumor that Brutus was Caesar’s illegitimate child, and thus a patricide as well as a killer of the pater patriae. (There is no historical evidence for this. Brutus’ mother did have an affair with Caesar, but it happened when Brutus was an adult.) The versions of the legend that have Caesar issuing final words carry a different meaning than the plaintive sorrow of the literal translation, or Shakespeare’s “Et tu Brute?” Kai su, teknon is the first half of a Greek proverb that suggested Brutus would get his comeuppance — “Even you, my child, will have a bite of my power.” It was less a lament than a curse. “Back at you, kid!” is how Tempest puts it. The scholar Jeffrey Tatum gives it a more contemporary gloss: “See you in hell, punk!”