The Ambassador Bridge arcs over the Detroit River, connecting Detroit to Windsor, Ontario, the southernmost city in Canada. Driving in from the Canadian side, where I grew up, is like viewing a panorama of the Motor City’s rise and fall, visible on either side of the bridge’s turquoise steel stanchions. On the right are the tubular glass towers of the Renaissance Center, headquarters of General Motors, and Michigan Central Station, the rail terminal that closed in 1988. On the left is a rusted industrial corridor — fuel tanks, docks, abandoned warehouses. I have taken this route all my life, but one morning this spring, I crossed for the first time in a truck.

I was in the passenger seat of a Cole Carriers freight hauler driven by Al Prevett, a craggy and chatty fifty-five-year-old Canadian with spiky white hair and scuffed black steel-toe boots. He had been driving back and forth over the Ambassador for seventeen years. We swapped stories of bumper-to-bumper traffic, cross-border bargain hunting, and surly American immigration officers. Prevett recalled an agent stomping into his RV, inspecting the fridge, and confiscating a tomato and a green pepper. “You can take a whole truckload across if you have the paperwork, but you can’t just take one,” he said. “Still, I find the border treats you the way you treat it.”

We were headed to a warehouse in Detroit to fetch four 18,000-pound coils of flat steel, which we would bring back to Canada to be stamped into hoods, doors, and other car parts. “They expect us to be on time, but then you might sit there waiting for hours,” Prevett said. The job requires patience and efficiency. Some drivers — not him — wear adult diapers and take amphetamines to avoid stopping.

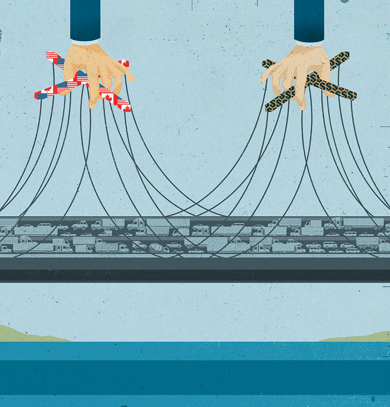

Illustration by Richard Mia

And then there’s handling the bridge itself, which is in bad shape. Riding up high in the truck, I could see the Ambassador’s condition as I had never been able to from my car. In some spots, the perimeter was lined with metal barriers; Prevett pointed out where the railings had rusted to flakes. There were holes in the curb so big you could see fishing skiffs bobbing on the waves below. Chunks of concrete, some almost two feet wide, had been known to drop from the underside. The bridge should accommodate four lanes, but repaving crews were there nearly every day, so it was now down to three.

Safety inspections have determined that the Ambassador, at eighty-eight years old, is safe enough. In an ideal world, it would be temporarily closed for repairs, but that is not an option. It is the fastest and cheapest route between the manufacturers on either side, and in 2016 truckers like Prevett used it to haul about $150 billion worth of goods — a quarter of all US-Canada trade. There is a tunnel under the river, but it’s too small for many tractor trailers. A truck ferry that scoots across the water can carry only 400 each day; it’s mostly used to deliver hazardous materials, which Michigan’s Department of Transportation won’t allow on the bridge. Taking the Ambassador out of commission would imperil thousands of American jobs.

There is another reason why the bridge has been left to deteriorate: it is the only major crossing into the United States owned not by a government but by a private company, which means that, as concerns go, it’s not apparent that public safety ranks above profit. There are 419 privately owned bridges in America (one of them is a pedestrian bridge between California and Mexico), but none are of the Ambassador’s size and importance.

Its owner, Manuel Moroun, is a ninety-year-old billionaire from Detroit who has devoted half his life and tens of millions of dollars to thwarting politicians who want to gain control of the border, and stymieing commercial competitors who want to break his monopoly. At age eighty-four he spent a night in jail for refusing to comply with a judge’s order that he complete ramps from the Ambassador to nearby expressways. He has donated to the campaigns of Michigan politicians and made alliances with unlikely bedfellows: Americans for Prosperity, the Koch brothers’ lobbying group; Detroit’s New Black Panther Party; and Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters. Moroun’s family corporations have sued or been sued dozens of times; bridge litigation alone has spawned some twenty cases. Bruce Heyman, who recently returned to the United States from a three-year post as ambassador to Canada, joked to me, “I had heard that just talking to him was reason enough for him to sue you, so I didn’t do that.”

There are many public officials in Detroit and Windsor who haven’t seen Moroun in years, or even met him. He avoids events and interviews (including with me), and it’s unclear how much power he has already passed to his heir, a forty-four-year-old son named Matthew (who also declined to talk). In pictures, Moroun looks like a squat, liver-spotted grandpa. A shopkeeper in Windsor told me, “He’s got this lively little face, with eyes like a leprechaun.”

Most people call him Matty. Forbes recently reported that he is worth $1.59 billion, but that is merely an estimate. In addition to the Ambassador — the tolls are believed to bring in about $60 million annually — he owns real estate operations, insurance firms, and customs brokerages. The family also runs several trucking companies, one of which made at least $700 million last year. Most of Moroun’s businesses are not listed on the stock market, so he has to share few details about what he does and earns. Headquarters is a converted middle school in suburban Detroit with no sign outside.

On paper, Moroun fits Donald Trump’s formula for infrastructure development, based on “unleashing private-sector capital and expertise.” He also reveals how problematic the result can be. The Ambassador is evidence that much can go wrong when public works belong to private owners — and beyond the bridge itself, the neighborhoods on each end have fallen into decay.

Prevett, who lives in Windsor, doesn’t have much choice but to keep driving across. We traversed the bridge without incident — there was nothing to declare or inspect on the empty trailer, and traffic that day was light. As we approached Michigan, however, he started to make me nervous. “When it’s packed on here, the whole thing starts to shake a little,” he said. He glanced over at me. “If it were really unsafe, I’ve got to believe they wouldn’t let us be driving over it.”

For decades before one was built, people wanted a bridge over the Detroit River, but neither the United States nor Canada had the cash. In 1921, the two governments passed laws allowing a private developer to control the project. In 1927, after funding was secured, construction on the Ambassador began. Moroun was born that year. His family, immigrants from Lebanon, had recently moved across the border from a Windsor neighborhood called Sandwich. Their house had been demolished to make way for the bridge.

Erecting the Ambassador took two years, and its opening coincided with the Great Depression. People celebrated anyway — in 1930 the actress Dottie Reid danced across it followed by a five-piece band; brides and grooms exchanged vows at its peak. Its builder, Joseph Bower, a Detroit native working on Wall Street, saved himself from bankruptcy by selling shares of the Detroit International Bridge Company to his creditors and listing it on the New York Stock Exchange.

Over the next decade, as the economy recovered and truck traffic rose, the Ambassador began to generate a profit. The Moroun family owned a gas station in Detroit, and business was good. When one of their customers, a two-truck delivery business, racked up a bill too large to pay, Tufick, Moroun’s father, took over the company. This was the start of what is today a transit empire (which includes Central Transport) with a fleet of trucks ten thousand strong, operating on both sides of the border.

In the late Seventies, Joseph Bower died, and his family decided to sell their controlling stake in the Ambassador. Moroun, by now running his family’s business, reasoned that they should buy; tolls would be dropped in their pocket. But he faced two obstacles: Warren Buffett was buying shares and could afford far more, and Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister, was determined to stop private investors from claiming ownership. Since the Ambassador was built, governments around the world had been increasing restrictions on private-sector investment in infrastructure, typically through a clause that transferred possession to the public after the investor made profits — an arrangement that has further evolved into what’s known as a public-private partnership.

For Trudeau, the Bower family’s exit was a chance to bring the Ambassador at least partially under Canada’s control. He insisted that any prospective buyer relinquish the Canadian half to the government within twenty-five years. Yet the Bowers were selling on the New York Stock Exchange; Canadian law applied only to the Canadian side. In 1979, Buffett, unwilling to accept Trudeau’s conditions or to bother fighting him in Canadian court, decided to sell his stake, $8 million, to Moroun. The rest of the shareholders followed. Moroun spent $32 million acquiring the Ambassador; when the purchase was complete, he checked the archives of the Canadian Transit Company for the deed to the old family house in Windsor, and presented it to his father.

As promised, Canada fought Moroun over the bridge. It took a decade for the two sides to reach a settlement. The terms were not made public, but Mickey Blashfield, Moroun’s spokesman, said that Canada agreed to recognize the family’s right to own the Ambassador in exchange for upgrades to customs booths and inspection facilities.

In the United States, Moroun sued for the right to sell duty-free gas at the base. Only cars traveling to Canada can fill up there, but he makes a considerable profit — likely as much as fifty cents a gallon. He doesn’t have to report sales, though in 2011 the Michigan Senate relied on an estimate from the Detroit Free Press: if each pump at his place were used once an hour instead of others elsewhere in the state, that would divert $14.4 million annually in would-be tax revenue to Moroun. Steve Tobocman, a former Michigan state representative who has dealt with Moroun, told me, “The bridge is a license to print money.”

By the turn of the century, more than 2 million drivers were crossing the Ambassador each year. On September 11, 2001, border security turned the usual traffic into a choke point. Vehicles piled up from the American customs plaza back over the river, through Windsor, and for another thirty miles beyond. A roadside economy appeared, with portable bathrooms and gas trucks for stalled cars. “There were pizza-delivery guys out there giving it away, and others charging triple the price,” Al Prevett recalled.

The companies that the drivers worked for were stuck, too. Manufacturers often request parts on an as-needed basis, rather than store them in warehouses. General Motors, for example, would place small orders for seats several times a day from a company in Windsor and expect them to show up five hours later. This can save money, but when there are delays, production can be suspended. If the Big Three were to close some factories temporarily, there would be a chain reaction throughout the American economy. “We created a war room to spot trucks in the line carrying auto parts and get them to the front of it,” Dan Stamper, the president of the companies through which Moroun owns the Ambassador, said. The truck ferry switched to a round-the-clock schedule, and this, along with a customs officer who was willing to work overtime, made it possible for GM to avoid sending home 1,449 employees.

Weeks later, when the backlog finally cleared, the American and Canadian governments realized how great the economic danger was, especially if the bridge itself became a terrorist target. They decided that a new crossing was necessary, to upgrade the route and to provide a backup during emergencies. Such projects begin with traffic, environmental, and engineering studies. Canada took the lead: How many cars and trucks would pass through in the next fifty years? How much greenhouse gas would come how close to how many homes?

Moroun also took note of the traffic jam, but he was quick on the draw. He launched into construction on a second bridge of his own, next to the Ambassador, that might stop the government from trying to build one or at least delay any competition. Without permission, he began work, filing lawsuits all the while to slow Canada’s progress. He was already among the biggest landowners in Detroit and Windsor, and now set out to buy more — in some cases demolishing properties soon after he purchased them. The residents who remained found themselves living among crumbling buildings and empty lots. Moroun’s mentality is that you don’t make money when you sell, a source close to him told me, you make money when you buy.

By 2009, Canada had its plan: a new bridge two miles south of the Ambassador, with six lanes, larger areas for customs and immigration inspections, and better safety precautions for trucks carrying hazardous materials. It would connect directly to highways instead of clogging city streets. Even if the tolls were set higher, the researchers believed, about 75 percent of the Ambassador’s traffic could be expected to favor the new bridge. Residents of Windsor wanted a bike path, so that was added to the design. Finally, the bridge was given a name: the Gordie Howe International Bridge, after the Canadian hockey great who led the Detroit Red Wings.

Canadian officials delivered this proposal to the relevant American authority, the Michigan Legislature. Moroun, on the other hand, made campaign contributions in Lansing; during the 2009–10 election cycle, his family gave at least $515,000 to state-level politicians. Sure enough, the legislature said no to the Gordie Howe plan, refusing to spend any money, citing the drop in tax revenue due to the recession. A year later, Canada returned, offering to pay for the whole thing. Mike Bishop — the Senate majority leader, whose political action committee had received $50,000 from the Moroun family the previous October — promised a vote, but it never happened. Jennifer Granholm, the governor at the time, said that the legislature’s ignoring a pitch for a free bridge was “Exhibit A for why Michigan needs campaign finance reform.”

Rick Snyder, who became governor in 2011, found a way around the legislature: the state’s constitution allows his office to cut a deal directly with a foreign government. “Sometimes people complicate things with politics,” he told me. “But common sense suggested a path, and we took it.”

He arranged for Canada to pay for everything, including ramps to I-75 in Detroit. Michigan would help acquire land on Canada’s behalf. The Gordie Howe would be built and operated by a private company for some thirty years, in a public-private partnership, and be co-owned by Canada and Michigan. (The state of Michigan has taken its lack of financial responsibility so seriously that the time Jeff Cranson, the spokesman for the Department of Transportation, spent talking to me for this story was covered by Canada’s monthly bill.)

Despite this development, Moroun wasn’t about to give up his own plans for a second bridge. In 2012, he sponsored a ballot proposal asking Michigan voters whether the state constitution should be changed to require their approval for any new bridge or tunnel to Canada. He spent $33.5 million on a campaign that implied, falsely, that the Gordie Howe would be built with taxpayers’ money.

One of Moroun’s allies in this effort was Malik Shabazz, the leader of Detroit’s New Black Panther Party. Before Election Day, The Daily Show sent Al Madrigal, a correspondent, to Detroit, where he asked, “So the leader of the Black Panthers is protecting an eighty-five-year-old white billionaire?” Shabazz replied, “In this town, I kick the ass. Not kiss the ass. Kick the ass.” When I spoke to Shabazz, he said that he and Moroun were natural allies, sharing a common opposition to Snyder, who is one of the least popular governors in America. “We’ve had our cities and our court systems and our schools taken over,” Shabazz said. “Folks can say what they want about the Morouns, but I’ll take them in a wheelchair over Snyder.”

The ballot proposal failed. Afterward, Moroun made a rare media appearance on Fox’s Detroit affiliate. Defending himself against opponents and the suggestion that he was a Dickensian villain, he said, “I stand for our country. If I was dressed up in the American flag, everything would be fine. I am the American flag.”

More recently, at public hearings, Moroun’s representatives have tried to convince members of the community that his bridge plan would serve them better than the Gordie Howe. Opponents accuse him of corrupting the democratic process. Last year, a reverend admitted to a local TV reporter that he’d accepted seventy-five dollars to speak in support of Moroun’s bridge. After a meeting, the reporter followed him to a gas station and filmed him receiving an envelope stuffed with cash.

My inquiries about who was recruiting “concerned citizens” led me back to Shabazz. He said that he had attended some public meetings but denied orchestrating phony testimonies. There was another group behind that, he told me, people targeting Detroit’s drug addicts. He added, though, that no one looking for quick cash was so different from the companies and elected officials seeking profits from a new bridge: “The politicians take their junkets, so what’s wrong with the little guy getting involved?”

Americans for Prosperity, the Koch organization, has also attempted to sway public opinion, posting fake eviction notices on houses in the Detroit neighborhood of Delray. The Koch brothers oppose government investment in infrastructure; in March, Freedom Partners, a group through which Americans for Prosperity is funded, released a memo lamenting “unnecessary regulations, mismanagement, and cronyism” common to federal spending on public works. “There is a right way and a wrong way to repair and modernize our infrastructure,” the statement read, “and it’s time Washington learned from its mistakes.” In Delray, where the Gordie Howe would land, notices advised residents to call the mayor’s office and oppose construction. Americans for Prosperity has denied ties to Moroun and wouldn’t disclose whether it had accepted money from him for the campaign, saying only, “It was meant to startle people.”

One morning, Drew Dilkens, the mayor of Windsor, drove me through Sandwich, the neighborhood on the Canadian side of the Ambassador. Dilkens and I went to high school together. Most of our classmates figured that he’d be mayor one day; from his post on the student council, he’d run our campus vending machines. When I reminded him of this, he replied, “Make sure you note that that was revenue-positive for the school.”

Now forty-five, he has angular features and wears thick-rimmed black glasses. He served on the city council for eight years before becoming mayor, in 2014, which has given him more than a decade of experience dealing with Ambassador-related matters. He has never met Moroun himself — the family usually sends his son Matthew to meetings. He’ll be polite, Dilkens explained, “but then a few weeks later we’ll be served papers in yet another lawsuit.”

As we approached the bridge, Dilkens pointed at rows of wooden planks bolted to the bottom, which were there to catch concrete before it fell on the road. They hovered over the site of the demolished Moroun homestead. Turning onto Wyandotte Street, we arrived at one of the ramps that Moroun’s company had begun building and then abandoned upon Canada’s order to stop work. There was one on the American side, too, now partially removed. These are known to critics as Dukes of Hazzard ramps. Dilkens joined the city council shortly after Moroun declared his intention to build a ramp to improve traffic flow. “Later we realized it was going to be part of his new bridge,” he said.

There are about 400 properties in Sandwich, Dilkens told me, of which Moroun’s companies own at least 163. In 2014, as houses emptied of families, J. L. Forster Secondary School closed because of low enrollment. Moroun now owns the building, bought through a third party. Stamper told me that the company wanted to improve its relationship with locals — in part since Matthew has been taking over executive power from his father — and that they’d converted the space into free offices for community groups. “We’ve had some self-inflicted wounds, and I understand there are people who wish we would go away,” Stamper said. Nevertheless, Moroun is tearing down thirty-three more houses in the neighborhood. Six residents have sued him for his damage to Sandwich, seeking $16.5 million.

I asked Dilkens whether he thought his town’s relationship with the Moroun family could ever improve. He shook his head. “There’s no conversation with Matty Moroun unless he gets a hundred percent of what he wants,” he said. “I don’t trust them.”

Later, I went to a bakery inside a historic two-story Georgian on Sandwich Street. There is an English-themed tearoom on the main floor, and Mary Ann Cuderman, the proprietor, lives upstairs. Cuderman, who resembles a wry Mrs. Claus, is the head of the Olde Sandwich Towne Business Association, and has been leading the local resistance against Moroun. Once, she told me, he paid her a visit.

“Matty walked in here with Skip McMahon, one of his guys,” she said. “He’s all of about five foot one or so. And I had a map on the wall. He points to the map and asks Skip, ‘So is this where the ramp goes?’ He must have been playing mind games with me — he knew where it was going to go! A week later, I got a call from a real estate agent asking how much I would want to sell my house. I said I’d never sell.” She went on, “If I ever win the lottery, I’m going to buy the house next door to Matty Moroun. And I’ll let the weeds grow.”

Until late summer, few people expected that the Canadian government would approve Moroun’s plan for another bridge. But in September, finding his paperwork to be in order, the federal transportation authority in Ottawa announced that it was granting him a permit. Cuderman and her neighbors were aghast; a round of newspaper editorials railed against Moroun’s scheming and questioned the government’s competence in allowing him to continue. Yet the permit was unusual, in that it came with a list of twenty-eight conditions that could make it unfeasible for Moroun to actually build a second bridge — including a mandate to tear down the Ambassador once the new one is completed. Brian Masse, who represents Windsor in Canada’s parliament, suspects that the permit was timed to assure political officials and private contractors before bids were made on the Gordie Howe. The transportation authority, he said, “needed to provide some certainty or nobody would bid on it. Now they have certainty that they’ll be competing against one bridge and not two.” Governor Snyder weighed in with a blog post, writing, “This approval does not impact the Gordie Howe International Bridge project, which is moving full-steam ahead.”

Even if Moroun meets all the conditions in the permit and obtains the last piece of property he needs in Detroit, Canada has essentially been cleared to build. In July, the City of Detroit announced its sale of properties, worth $48 million, to make way for the Gordie Howe. Mike Duggan, the mayor, said that he plans to use half the proceeds to buy out 450 homeowners in Delray. The area, now largely an industrial wasteland, may be developed into a logistics hub.

In Trump, a professed private-infrastructure enthusiast, Moroun has not found as much support as he might have hoped. While Duggan was wrapping up negotiations on city land, the White House was running Infrastructure Week — an ill-conceived program that served as an opportunity for Trump to fulminate against America’s permit system. Trump said that he wants to spend $200 billion on transportation projects, raise another $800 billion from commercial interests, and create a council to assist builders in securing whatever permits they need. But he outlined no specifics and has hired few administrators to realize that vision. His sole comment on the Ambassador Bridge debacle was a joint statement with Justin Trudeau, the Canadian prime minister, in February. “Given our shared focus on infrastructure investments, we will encourage opportunities for companies in both countries to create jobs through those investments,” they said. “In particular, we look forward to the expeditious completion of the Gordie Howe International Bridge, which will serve as a vital economic link between our two countries.”

Details about design and development are expected to be announced in 2018 by the Windsor Detroit Bridge Authority, the Canadian agency overseeing the project, which will select from among the three firms bidding to build and operate the Gordie Howe. Canadian officials have estimated that the project will cost around $4 billion, create 10,000 jobs in construction, and be done by 2023, though that may be optimistic — Amarjeet Sohi, the minister of infrastructure, said in October that he couldn’t be sure whether the bridge would be open ten years from now. “If we were building it ourselves this would be simple,” Masse told me. “But with a private partner it gets a lot more complicated.” So far, $2 billion has been spent on preparations. “We will build this project,” Sohi told Canada’s CBC News. “We need to make sure that we’re putting structures in place and that we build this bridge in a timely fashion and in a responsible way.” Snyder told me of the preliminary arrangements, “By doing all this work at the front end, you’re making sure you don’t end up with problems later.” He wouldn’t comment on Moroun directly, except to express frustration with “misinformation and information from other parties out there.”

If Moroun can’t stop the Gordie Howe, he will be unlikely to proceed with his own bridge; at a hearing in September, one of his lawyers said that would be “economic madness.” The next move for the family might be to cash in. Canada has offered to buy the Ambassador in the past, though Stamper has maintained that those talks were never serious. It remains to be seen how much longer Moroun will keep pressing ahead and resisting the big sale. “If they want it so much, they can come here and make us an offer,” Stamper said. “But otherwise we’re willing to risk it to keep going down this road.”

One morning, I drove to the dock of the Detroit–Windsor truck ferry. When I arrived, I entered a small immigration building and asked for Gregg Ward, the ferry’s owner. He spotted me and ambled over. He is fifty-six, six foot three, and ruddy. He wore stonewashed jeans and a fleece jacket. “Nice to finally meet!” he said, offering a big, swinging handshake. Apart from Moroun, Ward is the only person who stands to lose business upon the opening of the Gordie Howe; because it will accommodate trucks carrying hazardous materials, there will be no need for a ferry. Still, Ward is one of the bridge’s biggest supporters. “Stand back and look at the greater good,” he told me. “You build a new bridge to meet the needs of your economy, not the whims of this old man. Are you really going to base your economic vitality on one bridge that was built in 1929?”

He led me onto the ferry. A 158-by-55-foot deck barge attached to a tugboat, it hauls trucks back and forth along a one-nautical-mile route just south of the Ambassador. Ward can take eight trucks at a time, but when I arrived for the ten o’clock service, there were none, so we had plenty of space to lean against the tailgate of his white Ford and chat as we set off. In the bed of the truck were rolled-up blueprints for the Gordie Howe.

“It’s ridiculous that we even have to argue over whether we should build it,” Ward said. “A bridge is a utility that moves people and goods — that’s just the basic work of government. We’re in the heart of manufacturing here.” Ward told me that he was once a globe-trotting logistics consultant, but he can’t travel now. His ex-wife moved to Iceland along with their daughter, leaving him the sole caretaker of their adult son, who has autism. Running the ferry provides a steady income, and he can get home every evening at the appointed hour.

Sometimes he misses his old job — “It’s great experience to be out there,” he said — but he recently developed a ship-tracking system for the Great Lakes, and imagines that the Gordie Howe will bring more global economic interest to Detroit. “I’ve been here almost thirty years,” he said. “It’s a pretty rough place.”

To Ward, Moroun is a harmful distraction; he’d rather see the government focus on where thousands of workers will park their cars every day, and where to put the diggers and cranes and piles of rock. “This is the largest project ever in Michigan and Ontario,” he said. “This is the kind of stuff they should be thinking about. Not Moroun.”

Hardly anyone on either side of the water seemed to have the luxury of viewing things that way. But as we floated along, Ward seemed calm and certain. “This is going to be a new horizon for the economy,” he told me. “I’ll be able to find something else to do.”