In February 1947, Harper’s Magazine published Henry L. Stimson’s “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb.” As secretary of war, Stimson had served as the chief military adviser to President Truman, and recommended the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The terms of his unrepentant apologia (excerpt here) are now familiar to us: the risk of a dud made a demonstration too risky; the human cost of a land invasion would be too high; nothing short of the bomb’s awesome lethality would compel Japan to surrender. The bomb was the only option.

Seventy years later, we find his reasoning unconvincing. Entirely aside from the destruction of the blasts themselves, the decision thrust the world irrevocably into a high-stakes arms race — in which, as Stimson took care to warn, the technology would proliferate, evolve, and quite possibly lead to the end of modern civilization. The first half of that forecast has long since come to pass, and the second feels as plausible as ever. Increasingly, the atmosphere seems to reflect the anxious days of the Cold War, albeit with more juvenile insults and more colorful threats. Terms once consigned to the history books — “madman theory,” “brinkmanship” — have returned to the news cycle with frightening regularity.

In the pages that follow, seven writers and experts survey the current nuclear landscape. Our hope is to call attention to the bomb’s ever-present menace and point our way toward a world in which it finally ceases to exist.

CONTRIBUTORS

Rachel Bronson is the executive director and publisher of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Mohammed Hanif’s third novel, Red Birds, will be published next year by Bloomsbury.

Lydia Millet’s next book, the short story collection Fight No More, will be published in 2018 by W. W. Norton.

Theodore Postol is a professor emeritus of science, technology, and national security policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Elaine Scarry is a professor of English at Harvard University. She is the author of Thermonuclear Monarchy: Choosing Between Democracy and Doom (W. W. Norton).

Eric Schlosser is the author of Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety (Penguin).

Alex Wellerstein is a professor of science and technology studies at the Stevens Institute of Technology, and a principal investigator at the Reinventing Civil Defense project.

Final Countdown

By Rachel Bronson

Thanks for scaring the shit out of my eleven-year-old daughter,” read one of the angry emails that I received in January. I have an eleven-year-old daughter myself. It was a terrible email to open.

A few days earlier, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, where I serve as the executive director, had fixed its Doomsday Clock at two and half minutes to midnight. It had not been set so late since 1953, after both the United States and the Soviet Union tested hydrogen bombs, bringing mankind to the brink of its own destruction. Only eight years after World War II, nuclear weapons had become hundreds of times more powerful than the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Surely the world in 2017 was better off than it had been back then. Perhaps my angry emailer had a point. Perhaps, even in these perilous times, the clock had been set too close to midnight.

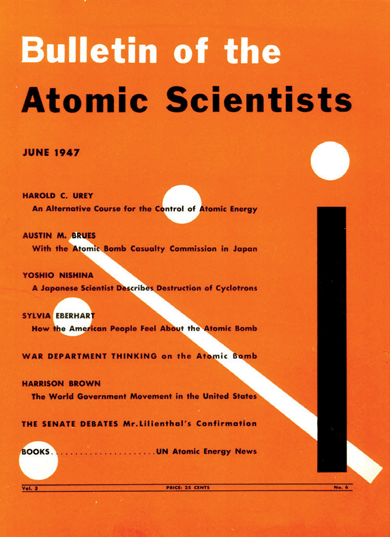

The Doomsday Clock was created in 1947 by the landscape artist Martyl Langsdorf at the request of her husband, the physicist Alexander Langsdorf. Two years earlier, he had been part of a group of Manhattan Project scientists at the University of Chicago who put together the six-page, black-and-white Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists of Chicago in response to the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan. These scientists had played a role in unleashing nuclear power, and now they resolved to mobilize the public to insist on policies that would prevent such weapons from ever being used again. The bulletin became a must-read for anyone concerned with managing scientific advancement, but it still needed a riveting cover. Enter Martyl, who created the Doomsday Clock for the June 1947 edition. It was set at seven minutes to midnight.

Since the clock first appeared, the minute hand has moved forward and backward, as close as two minutes to midnight in 1953 and as far away as seventeen minutes in 1991 — when, at the end of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which promised deep cuts in the arsenals of both countries. The Doomsday Clock has long since become a resource for the public to demand better policies and diplomacy from its leaders, to push ourselves farther from midnight.

Today, as a result of diplomatic efforts, the United States and Russia have cut their stockpiled nuclear warheads to fewer than a combined ten thousand. Confidence-building measures designed to reduce tensions have been in place for decades and have proven effective. Why then has the Doomsday Clock ticked forward to two and a half minutes to midnight?

Cover of the June 1947 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists depicting the Doomsday Clock, by Martyl Langsdorf. Courtesy Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Over the past two decades, as the American public happily convinced itself that atomic weapons were no longer a worry, new nuclear powers emerged, posing new threats. Beyond the known nuclear states — the United States, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom — and the undeclared but long-recognized weapons program maintained by Israel, other countries have entered the fray. India and Pakistan began actively testing new nuclear weapons in a tit-for-tat race starting in 1998, and Pakistan now has the fastest-growing arsenal on the planet. Lest anyone think that a nuclear exchange between these two countries would confine its carnage to the subcontinent, research shows that it would likely send plumes of smoke from firestorms into the atmosphere, leading to a global nuclear winter that would destroy crops around the world and lead inevitably to famine. What happens there — what happens anywhere — affects us all.

Farther north, President Trump’s reckless language at the United Nations and in recent tweets is making the already dangerous standoff with North Korea even worse. The country has conducted no fewer than six nuclear tests, and Kim Jong-un claims to have developed a hydrogen bomb, making his arsenal considerably more powerful than what intelligence analysts believed was possible just a few years ago.

The United States and Russia, therefore, are no longer the only actors driving today’s nuclear reality, though they still have an important role to play given that they control around 90 percent of the world’s nuclear stockpiles. What looked earlier this year to be a warm relationship between the Trump and Putin Administrations seemed to promise the ratcheting-down of tensions, but we’ve seen the opposite taking place. This fall, the Russians staged military exercises that rehearsed the use of nuclear weapons. The United States plans to invest a trillion dollars over thirty years in a new arsenal, one that could require a new round of testing in violation of long-established norms and agreements. This past August, the US Air Force announced a $1.8 billion plan to develop a nuclear-tipped stealth cruise missile, and will donate nearly $700 million to begin replacing our arsenal of aging Minuteman missiles.

Just days after I received the original email, I received another, from a thirtysomething woman in Philadelphia. Rather than question the Doomsday Clock’s setting, she thanked us. The clock reflected her belief about today’s nuclear reality, and it gave her some comfort that experts agreed. She hoped that the 2017 clock would focus global attention on the world’s increasingly precarious state.

Though a symbol like the Doomsday Clock evaluates the prospect of nuclear annihilation, it can also be a source of hope. With American public support and engagement, we can pressure our decision makers to take action to move the clock’s hands away from midnight rather than let them tick toward it. With widespread and organized efforts, we can persuade our leaders to do the hard work needed to reverse course with Russia, protect the Iran deal, limit the power of the president to authorize a first-strike nuclear attack without a congressional declaration of war, and reallocate scarce capital away from a new nuclear arsenal. Perhaps we can finally stop scaring eleven-year-old girls who have plenty of other things to worry about. We have reversed the hands of the Doomsday Clock before. We can do it again.

“Subsidence Craters, Northern End of Yucca Flat, Nevada Test Site,

1996” © Emmet Gowin. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York City

Nuclear Citizenship

By Elaine Scarry

A nuclear weapon, like any weapon, has two ends: the end from which it is fired and the end through which it inflicts injury. But in the case of nuclear weapons, there is a unique disproportion between the two ends. The injuring end has the capacity to kill hundreds of thousands of people instantly. The firing end, by contrast, requires only the will of a single person — or at most a set of persons whose numbers are infinitesimal compared with those who will be harmed.

In theory, laws are already in place to invalidate nuclear weapons. International laws explicitly restrict what happens at the injury end. The Geneva Protocol prohibits weapons that inflict disproportionate suffering. The Hague Conventions prohibit weapons whose lethal effects can spread to neutral regions and affect innocent populations. The UN Convention on Genocide prohibits acts committed with “the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” Other treaties — such as the Rio Declaration and the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer — name the earth itself, rather than people, as the injured party.

At the other end, the firing end, individual constitutions provide constraints that also ought to forbid the use of nuclear weapons. Some constitutions stipulate that the country cannot initiate war unless a large number of citizens agree that the putative enemy has done something to warrant it. Furthermore, they require that the demonstration of this consent be individually burdensome and costly, something more than the click of a mouse or an anonymous poll.

The Constitution of the United States is one such document. It places two impediments in the way of initiating war. The first is well known: the requirement for a declaration of war by Congress. The cost to lawmakers is the obligation to deliver open arguments, subject to rigorous testing, and climaxing in a roll-call vote that makes the yea voters responsible for whatever follows. The other impediment is less familiar but is implicit in the Second Amendment: confirmation by the population, which is given agency over the weapons. The cost to them is the risk of death if one agrees to fight, and the risk of ostracism or jail if one declines. Giving a voice to the citizenry as well as to legislators is key. In the debates surrounding the creation of the Constitution, the Founders repeatedly stressed that people of all ages, economic groups, and regions must be given authority over arms.

The US Constitution is not unique in stipulating such constraints. The constitutions of several other nuclear states — France, Russia, and India — assert that the legislature, not the executive, has responsibility for authorizing the country’s entry into war. And the Russian constitution includes a provision that is a close cousin of the Second Amendment’s right to bear arms: it states that all adult Russian citizens bear responsibility for defending the country.

Despite the international and domestic frameworks that would seem to outlaw the existence of nuclear weapons, a handful of individuals — Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, and Kim Jong-un among them — currently possess the ability to condemn entire populations to sudden extinction. How did this come to pass? Given the stark incompatibility of nuclear weapons and legislatures, citizens, constitutions, and international laws, how have such weapons persisted and flourished?

One usual answer is that nuclear weapons cannot be unmade. But that is obviously false. The nine nuclear states are confined to the Northern Hemisphere; the Southern Hemisphere is blanketed with treaties making those continents and countries free of nuclear weapons. It wouldn’t be difficult for nuclear-armed nations to accomplish the same. A Scottish study, for instance, has established a concrete timetable for disassembling the United Kingdom’s nuclear arsenal. Some parts of this work (dismantling the nuclear triggers) would take hours, other parts (bringing the submarines into port), days, but the UK could ditch its nuclear weapons entirely in four years. Compared with global warming, unmaking these bombs is simple and straightforward.

Nuclear weapons have persisted not because they resist dismantling, but because they have infantilized and miniaturized our political institutions. Ever since the atomic bomb and its successors enabled leaders to wipe out millions instantly, US presidents have not bothered to seek a congressional declaration when initiating a conventional war (Korea, Vietnam, the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Afghanistan) or carrying out an invasion (Panama, Haiti). Congress, when it acted at all, issued enfeebled forms of authorization or conditional declarations. Deprived of its single greatest constitutional duty (what Justice Joseph Story once called the cornerstone of the Constitution), Congress became irrelevant at best.

During the first three decades of the nuclear age, the citizenry remained more involved than Congress, simply because the population was still needed to carry the weapons onto the battlefield. But once conscription was eliminated after the Vietnam War, and a voluntary army could be supplemented by contractors who served as the president’s private military, the citizenry, too, forgot that it was responsible for authorizing the use of the country’s arms, and finally concluded that its only responsibility was to watch executive-ordered violence unfold on television.

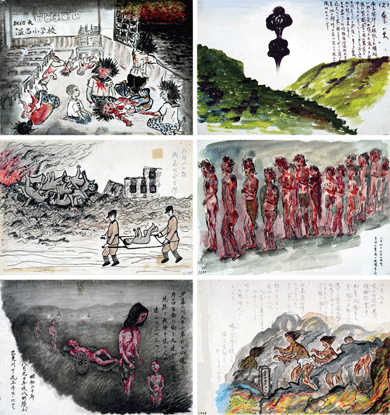

Clockwise from top left: drawings by Takeda Hatsue, Takemoto Hideko, Yamashita Masato, Murakami Misako, Furukawa Shoichi, and Yokota Haruyo, who survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Courtesy the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

When the Founders described the right to bear arms as the “palladium of liberty,” they were not speaking of our right to carry a gun into a drugstore or a university classroom. They were speaking about the population’s collective power to say yes or no to war. Similarly, when John Locke described the legislature as the “soul” of any democratic government, he was speaking first and foremost about the constraints that the legislature imposed on the executive impulse to go to war.

Over this seven-decade affair with nuclear weapons, we’ve forgotten that we still have the constitutional tools to eliminate them. We have both the moral responsibility and the legal means to enable legislatures and citizens to recover their rightful stature, and to rid the world, finally, of these obscene instruments of devastation.

Countermeasures

By Theodore Postol

Those who touch us will not escape death! threatened one. a revenge attack of annihilation! promised another. strike the united states with nuclear thunderbolts! The language on the signs at a mass rally this August in Pyongyang, North Korea, was familiar: for decades, the pugnacious state has had a taste for hyperbolic threats, while its actual ability to strike the US homeland has lagged far behind. No matter how apocalyptic the rhetoric, Americans could take comfort in the fact that North Korean missiles weren’t going to rain down on the West Coast anytime soon.

A month before the rally, however — on July 4 — the regime launched a new ballistic missile, more sophisticated than the duds that used to plummet ineffectively into the Sea of Japan. The Hwasong-14 landed less than 600 miles away from its launch site, but analysts nevertheless predict that it could carry a small payload to Seattle. It remains unclear whether the new missile could successfully deliver a nuclear warhead, but at North Korea’s current pace, the technology could be in the not-too-distant future.

Officially, of course, we have nothing to fear from such attacks. After a much-touted test in May of the $40 billion Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, designed to intercept intercontinental ballistic missile warheads in the near-vacuum of space, Jim Syring, then the director of the US Missile Defense Agency, declared that “we have a capable, credible deterrent against a very real threat.” In October, President Trump put his own estimate of the interceptors’ success rate at 97 percent.

There is little basis for this optimism: in the real world, the system is a flop. Despite being tested under highly choreographed and artificial conditions, the GMD has failed 55 percent of the time since coming online in 2004. In a real combat situation, it is highly likely the system’s failure rate would be considerably worse: not exactly favorable odds when nuclear annihilation is at stake.

Once fired, an ICBM goes through three distinct phases of flight before it reaches its target. The first phase, known as the boost phase, lasts between three and five minutes, after which the missile’s engines shut off. The warhead then detaches from the rocket and enters the midcourse phase known as free flight, cruising through space for roughly twenty-five minutes under the dual influence of gravity and momentum. Finally, there is reentry: the warhead plunges back into the dense lower atmosphere and, if all goes well, wreaks its havoc at ground zero.

Since the threat of a long-range attack first emerged in the 1950s, the United States has focused on ground-based anti-ICBM systems designed to intercept missiles during free flight. Nike-X (canceled in 1967 because of its exorbitant costs and ineffectiveness), Sentinel (canceled in 1969 after complaints about proposed launch sites in suburban neighborhoods), and Safeguard (canceled in 1976 after being operational at a single base for less than a year) all functioned according to the same principle.

The fundamental problem with these systems is that they are easily fooled. An interceptor homes in on its target by means of infrared sensors. To these devices, an incoming ballistic missile is virtually indistinguishable from other objects until the final two to three seconds before impact. During the rest of its trip, the interceptor sees only undifferentiated points of light. This makes the system vulnerable to simple countermeasures. An adversary might confuse the interceptor’s sensors by deploying balloons along with a warhead, or by breaking the trailing upper rocket stage into a multitude of fragments.

Even if the interceptor lucks out and happens to lock on to the proper target, it has to strike the warhead with extreme accuracy, often within a range of several inches. The smallest error leads to total failure. Given these weaknesses, a baseline of psychological comfort is really all a system like GMD has to offer.

So what might a workable missile defense system look like? To begin with, it would have to destroy its target during the boost phase, before the ICBM is able to exit the atmosphere and commence its smoke-and-mirrors routine. Assuming Pyongyang makes further improvements to the Hwasong-14, the defense system would have only four minutes in which to detect the launch, fire interceptors, and destroy the North Korean missile. The interceptors, in other words, would have to be based close to the peninsula. Ground-based missiles, in addition to being politically thorny, are immobile, and require considerable defenses of their own. Sea-based interceptors are more flexible and less vulnerable, but could fall victim to a submarine attack.

The most viable option, then, is to position our interceptors in the sky itself. A fleet of airborne drones, equipped with fast-accelerating interceptors, may be the only way to reliably prevent a successful North Korean ICBM attack. Patrolling at high altitudes, these drones can stay aloft for thirty to forty hours. Each can carry two anti-ICBM interceptors, which can also be used to shoot down satellite launches.

A drone-based program that is already under development at the Missile Defense Agency is reliant on aircraft designed to carry heavier payloads at higher altitudes. These drones have yet to be built, however, and are intended to be equipped with lasers that no one quite knows how to engineer. Given the urgency of the North Korean threat, we need a weapons system grounded in current technology rather than science fiction.

The vision of a panoptic drone army hovering over the Sea of Japan might strike some as dystopian, imperialist, or simply quixotic — to say nothing of the alarm it would cause in Moscow and Beijing. Handled sensitively, however, an air-based system would be a far more technologically effective way of shielding the West Coast from an incoming Hwasong-14. More to the point (assuming the Trump Administration desires a peaceful resolution), the presence of such a system might prod Kim Jong-un into pursuing a diplomatic solution to the current standoff. With its missile program rendered impotent, North Korea might be willing to approach the bargaining table with an eye toward de-escalation. Offense, as the saying goes, might actually be the best defense — and the only way to avoid a catastrophically destructive war.

Our Bomb

By Mohammed Hanif

Our bomb — the Pakistani bomb — isn’t just a weapon constructed in a nuclear lab by a bunch of overqualified scientists. It’s an extension of our foundational myth, according to which Pakistan wasn’t merely the result of an anticolonial political struggle but an act of God. Our myth of the bomb involves a Dutch-trained metallurgist, A. Q. Khan, who became a national hero and was christened the Father of the Bomb. He was later disgraced on national television for selling our nuclear secrets. It involves a popular prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who pledged that we would make our bomb even if we had to eat grass. Bhutto was hanged. The myth also involves a military dictator, Mohammed Zia-ul-Haq, who innocently asked, “What bomb?” The Americans knew that Pakistan was developing an atomic weapon, but they needed Zia for their proxy wars, so they looked the other way while we quietly begged, borrowed, and stole to build our bomb.

Pakistan’s nuclear program was born a year after the country’s breakup, a trauma so intense that we have almost erased it from our history. After decades of misrule and a world-class massacre, East Pakistan — now Bangladesh — declared independence in 1971. Our archenemy India intervened, and three divisions of the Pakistan Army surrendered in Dhaka. Its celebrated soldiers became POWs. Pakistan’s elite, who had fed the population stories of our martial prowess, found it hard to live with the fact that our old foe had inflicted a fatal wound. And if India could do it once, what would stop India from doing it again?

Soon after our soldiers returned home from their ordeal in prison, India carried out its first nuclear test. The enemy had made its intentions clear. The enemy was developing the instrument of our total humiliation. This was our moment to eat grass and make our bomb.

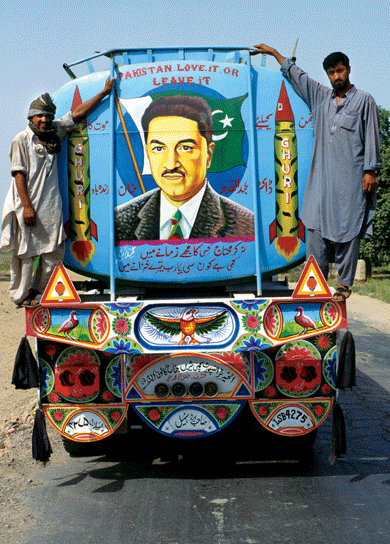

A portrait of A. Q. Khan, the father of Pakistan’s nuclear program, painted on a tanker © Piers Benatar/Panos

It was between that moment and Pakistan’s first test, twenty-four years later, that our nuclear mission became part of our national mythology. At least some of these myths were perpetuated to bolster our fragile egos. When the West described Pakistan’s nuclear program as an attempt to build an Islamic bomb rather than a nationalistic enterprise, we rejoiced that we were finally the Muslim world’s undisputed protector. It fed into our narratives about our promises to liberate Kashmir, Afghanistan, Palestine, even Chechnya. It didn’t bother us that we hadn’t brought any of them closer to their respective ideas of freedom. We had ensured ours. But at what cost?

We are not quite eating grass, but we are severely malnourished. Twenty-three million of our children are out of school. Hundreds of women are killed each year in the name of honor. But we know that there is a big bad world out there. And that world can’t touch us because we have our bomb. It gives us the power to think like a superpower.

Sometimes, however, we worry that our bomb hasn’t quite given us the all-encompassing protection we need. We have taken more than eighty thousand casualties in the so-called war on terror — domestic and otherwise — over the past fifteen years. We can hardly use the bomb against the men hiding in our own cities, blowing up our own citizens. Our bomb is for others.

Sure, as soon as there is a scare on the borders, there are sleepless nights in Western capitals because of our bomb. Diplomats rush back and forth between Delhi and Islamabad trying to calm our nerves. There is always this fear — a fear that we relish — that if we feel an existential threat to our country, we might use our bomb.

But we have an even greater fear: someone might steal our bomb and use it against us, or our friends, or our enemies. Western countries like spreading this fear. Every few months, there is a think tank report or a newspaper analysis that asks: Is Pakistan’s nuclear program safe? Can rogue elements get access to Pakistan’s weapons? Can one of Pakistan’s many enemies destroy their bomb? On these questions we are united. Those who love the bomb and those who feel squeamish about it all agree that our bomb is as safe as your bomb. It’s actually safer than any bomb in the world. Many newspaper stories in the Western press refer to Islamabad as that place forty miles from Pakistan’s nuclear facilities — as if they have our bomb’s postal code. They don’t know what they’re talking about. We can’t really tell anybody, let alone our own citizens, how safe our bomb is, or what pains we have taken to keep it that way. If we told you how we’ve made it safe, then what would be the point?

Sometimes the doubters among us wonder if ours is the only nuclear deterrent in the world that, rather than protecting us, needs our protection. In a perverse kind of way, we are always pledging to keep our bomb safe. We don’t really feel like the owners of an amazingly destructive power, it seems, but like a poor widow who has only one family jewel and believes everybody is out to rob her.

Some of us who don’t love the bomb as much as they should wonder if the bomb really has made us safe. They seem to think that it has protected militants who intend to harm our neighbors, and sometimes our own people. Nobody is going to come after them, because they are operating out of a sovereign country with a bomb, and we keep reminding the world that we’ll use this bomb if our sovereignty is threatened. Sometimes we have to stretch the definition of our sovereignty in order to keep our bomb safe. We are still not sure whether it was Osama bin Laden who violated our sovereignty by taking refuge here, or the Americans, by barging in one night and killing him. Sovereignty is a complex notion. Our bomb is much simpler. Let us keep it that way.

That simplicity was channeled by one of our most influential media moguls, Majid Nizami, who said that his last wish was to be tied to our bomb and dropped over India. He died of old age a couple of years ago. But his dream, like our national mythology, lives on. If our bomb can’t save us from our daily mayhem, it can still put the fear of God into our enemies’ hearts. It can definitely teach India a lesson, even if that lesson means our shared destruction.

Haywire

By Eric Schlosser

The first atomic bombs in the American arsenal were built by hand. The Mark 3 model, which was used to destroy the city of Nagasaki, was difficult to assemble. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific director of the Manhattan Project, called it a “haywire contraption.” It contained about 14 pounds of plutonium, 250 pounds of uranium, 5,000 pounds of conventional high explosives, and dozens of cables linking fuses to detonators. The plutonium core couldn’t be left inside the bomb for too long because the heat it radiated would melt the explosives. The Mark 3 was powered by a car battery that took three days to charge and died within a week. If you wanted to change the battery, you had to disassemble the bomb.

During the late 1940s, the complexity of America’s nuclear weapons and the limited range of its bombers meant that a full-scale nuclear attack on the Soviet Union would take weeks to complete, if not months. A decade later, nuclear weapons were being mass-produced. They came in a variety of sizes, shapes, and explosive yields. Technological innovations — boosting, composite cores, thermal batteries, thermonuclear fuels, and other byproducts of high-speed computing — allowed the manufacture of powerful, ready-to-use “wooden” bombs. They could be stored for long periods without any maintenance, safe and inert, like planks of wood. The introduction of jet engines and aerial refueling soon enabled the bombers of the Strategic Air Command to strike the Soviet Union within hours. A nuclear war would probably end within days.

Technological advances continued to compress time and increase the risk of a nuclear catastrophe. In 1957, the launch of Sputnik, the world’s first man-made satellite, aroused fears in the United States that the Soviet Union had taken the lead in rocketry and high-tech research. While the public focused on the problems with science education in American elementary schools, the Pentagon worried about a much graver threat. The same sort of launcher that put Sputnik into orbit could be fitted with a nuclear weapon and turned into an intercontinental ballistic missile. It might deliver a Soviet warhead to American soil in about half an hour. By the 1960s, the time frame of a nuclear attack had grown even shorter. American submarine-launched ballistic missiles could hit Moscow in about fifteen minutes. By the 1980s, American medium-range missiles based in West Germany could hit it in about six.

A survivor with radiation burns, Hiroshima. Courtesy the National Museum of Health and Medicine/Science Source. © Photo Researchers Inc.

The increased speed of a nuclear attack placed enormous pressure on high-level decision-making. During an international crisis, a leader no longer had weeks, days, or even hours to choose a course of action. Amid concerns about surprise attacks, “decapitation” strikes against civilian leadership, and attempts to disable military command-and-control centers, there was a perverse logic to striking first. It encouraged a belief in the need to “use it or lose it.” False alarms, miscalculations, mistakes, accidental launches, accidental nuclear detonations, and even accidental nuclear wars became more likely. Faced with an international crisis, how could anyone be expected to make the right decision in just five or ten minutes with the fate of the world at stake? In retrospect, the fact that the Cold War ended without a single city disappearing in a nuclear explosion seems nothing short of miraculous.

Today, the time frame of an attack has been reduced to mere seconds. It once took three or four nuclear warheads aimed at every silo to render an adversary’s missiles useless, a redundancy thought necessary for certain destruction. Intercontinental ballistic missiles may now be made inoperable with a single keystroke. Computer viruses and malware have the potential to spoof or disarm a nuclear command-and-control system silently, anonymously, almost instantaneously. And long-range bombers and missiles are no longer required to obliterate a city. A nuclear weapon can be placed in a shipping container or on a small cabin cruiser, transported by sea, and set off remotely by cellular phone.

A 2006 study by the Rand Corporation calculated the effects of such a nuclear detonation at the Port of Long Beach, California. The weapon was presumed to be two thirds as powerful as the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima in 1945. According to the study, about 60,000 people in Long Beach would be killed, either by the blast or by the effects of radiation. An additional 150,000 would be exposed. And 8,000 would suffer serious burns. At the moment, there are about 200 burn beds at hospitals in California — and about 2,000 nationwide. Approximately 6 million people would try to flee Los Angeles County, with varying degrees of success. Gasoline supplies would run out. The direct cost of that single detonation was estimated to be about $1 trillion. In September, North Korea detonated a nuclear device about thirty times more powerful than the one in the Rand study.

Technological advances can’t easily be reversed. But strict controls can be placed on dangerous technologies. New inventions may someday reduce the nuclear threat by improving early-warning systems, preventing cyberattacks, detecting bomb-making materials, improving communication between adversaries during a crisis, and aiding in the verification of arms-control agreements. Relying on technology to safeguard humanity against technology does not, however, seem like a safe bet. Because of the greatly accelerated speed of nuclear warfare, we are literally running out of time.

Old-fashioned personal interactions may be our last, best hope of averting disaster, and international diplomacy may achieve what microchips cannot. Dialogue, confidence-building, regular meetings between the military and civilian leadership of nuclear states may not only prevent international crises, they may ensure that a misunderstanding won’t swiftly lead to mutual annihilation.

Sleeping Giants

By Lydia Millet

Once there were eighteen of these sunken giants in a ring around Tucson, Arizona — eighteen underground silos surrounding this desert city. Each housed a Titan II missile more than ten stories tall, tipped with the most powerful nuclear warhead ever deployed by the United States.

They were massive weapons, named for a race of ancient gods, but their life span was brief, from the height of the Cold War, in 1963, to 1987, when their now-obsolete technology cost too much to maintain. The missiles were promptly dismantled and the silos blown up, caved in, sold off to private parties — all except one. That one, south of the city, on a highway that runs down to Mexico, was turned into a museum. Today I’ve driven there in 110-degree heat to tour it with my nine-year-old son.

The parking lot is all bare sand and concrete, plus a kind of tepee-shaped antenna I’ve never seen before. Beyond a chain-link fence, a Plexiglas pyramid is visible — from which, says a fellow tourist as we wait for the doors to open, we’ll be able to look down at the missile in its 150-foot shaft. The pyramid reminds me of the Louvre.

After we buy our tickets and join a tour group, we’re led across the hard, bright sand to a hatch in the ground. Our guide, Scott, is a gray-haired man in a hard hat and a light-blue shirt. He tells us that the Titan IIs were tipped with the nine-megaton W53, whose explosive force was about 600 times that of the bomb that leveled Hiroshima. They weren’t considered first-strike weapons, he says. You could destroy a whole nation with our local collection of Titans — to say nothing of the three dozen around Wichita and Little Rock — but only after the other guy started it.

There were always four crew members in the launch-control complex, Scott tells us, and for most of the 1970s, he was one of them. He never would have thought, back then, that he’d return here of his own free will. He never would have thought that he’d choose to spend his far-off retirement as a tour guide in this hole in the ground. But almost forty years later, here he is.

He seems mildly puzzled about it. He says: “Here I am.”

We descend some flights of metal stairs. A coolness envelops us. The walls are concrete and four feet thick, and everything is painted an institutional green. There’s a door that weighs three tons but swings open easily. Stenciled on the wall beyond are the words no lone zone. two man policy mandatory. One person alone could not be trusted when it came to nine-megaton warheads.

In the control room are banks of pale-green metal cabinets with rows of quaint analog buttons, chunky and obvious as Fisher-Price toys. They must be satisfying to push, I think. We hover around the edges of the room on the brown carpet, gazing expectantly at Scott, who rattles off his narrative of daily life in the silo. There was a kitchen, but the crew rarely cooked. “Cooking wasn’t an issue,” he says. “It was cleaning up afterward. I tell you, Pepsi and Twinkies make great alert food.” He was twenty-three when he started here.

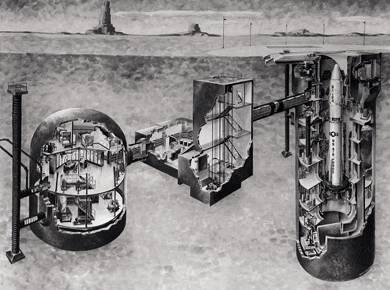

Illustration of a Titan II silo. Courtesy the Titan Missile

Museum/Titan Missile National Historic Landmark

I’m not angling for it, but Scott chooses me to act as commander, along with a young mother who has an infant strapped to her chest. When the signal is given, we’ll turn the paired keys to pantomime a launch. I sit down at a Formica-topped desk in front of an array of buttons. The two of us tell everyone our names. And, obligingly, the array tells me its name: launch control console.

The buttons say ready to launch. launch no-go. umbilicals not connected. target 1, target 2, target 3. “Crew never knew what the targets were,” says Scott. “Didn’t want to, either.” My little boy detaches himself from the crowd and plunks down onto my lap. He sits there as Scott talks, occasionally kissing my cheek softly in sudden, public affection. “Women joined the crew in the 1970s,” Scott tells us. In fact, the director of the museum was one of the first women to ever pull a Titan II alert. It’s clear he’s proud of the role women played in the story of mutual assured destruction.

On Scott’s signal, the younger woman and I, both with our boys clutching us, obediently turn our keys. A Klaxon blares. Chunky buttons light up and flash red and green and yellow. After we’ve all predictably flinched, the system shuts off.

There’s a silence. Is it a letdown? The flatness of the mundane? A form of sadness? It was easy to turn the keys. As easy as nothing.

And now there’s nothing left to do. If the exercise had been real, the launch would have taken about a minute. With a gentle push from me, my son clambers off my lap. “This is, like, history,” says a guy next to me as we file out. He’s the only one talking, here in the anticlimax.

History, sure, but history isn’t done. In other silos dotted across Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming, 450 newer, sleeker missiles wait in their hidey-holes. The Minuteman IIIs, scheduled for phaseout in 2030, are smaller than their ancestors and carry three warheads, more modest than the W53 but still good to deliver at least twenty Hiroshimas. ICBMs by the hundreds ready to fly, still and always.

As I shuffle out, holding my son’s hand at the back of the crowd, I have the subdued feeling I’ve had leaving funerals. And even weddings. Sermons, movies. We emerge into the baking sun and file past Scott, who’s presiding over our exit rocked back on his heels, his hands clasped behind his back like a statesman.

I smile at him uncertainly and want to say: Why are you still here? Why did you come back? They must have been tedious and lonely, those long, long shifts he pulled in front of the Fisher-Price doomsday button. But I can’t summon the courage to ask.

What We Lost When We Lost Bert the Turtle

By Alex Wellerstein

You may be in your schoolyard playing when the signal comes. That signal means to stop whatever you are doing and get to the nearest safe place fast. Always remember: the flash of an atomic bomb can come at any time, no matter where you may be. . . . Sundays, holidays, vacation time, we must be ready, every day, all the time, to do the right thing if the atomic bomb explodes.

Such was the message given to American schoolchildren in the 1950s, an introduction to a new world in which the United States no longer had a monopoly over nuclear weapons. It was a message that aimed to prepare, not frighten, though it spoke of nuclear war not only as an if but as a when. The name given to this educational effort was Civil Defense, and its mission was to reduce the mortality rate in the event of a nuclear war and prepare the survivors for a swift recovery.

The Federal Civil Defense Administration, established in 1950, took on a range of tasks, coordinating efforts to identify spaces that could be repurposed as fallout shelters and persuading suburban homeowners to construct their own bunkers. The goal in all cases was to save lives downwind of the hundreds of anticipated ground zeros.

But the FCDA is now remembered mostly for drills in which elementary school students took cover under desks. Other simple rules of thumb included backing away from windows if one saw the blinding light of a mushroom cloud on the horizon, to prevent injuries from shattered glass.

The best known of these efforts may be Duck and Cover, a nine-minute film released in 1951. Its star was an animated turtle named Bert. The film was aimed at schoolchildren, and its message was simple: nuclear war could erupt at any time, and if it did, survival might depend on whether students could rapidly find shelter — from hunkering down in public blast shelters to hiding under tables, in doorways, or in gutters. (Or, in Bert’s case, retreating into his own shell.)

Could hiding under a desk really save one from a nuclear attack? Depending on the type of attack, the type of shelter, and the distance of the detonation, it could indeed make a difference. But the ostensible futility of the survival techniques was enough to make the FCDA a subject of derision by the late Cold War, especially as the quantity and megatonnage of the Soviet arsenal grew to apocalyptic proportions. For the antinuclear crowd, it was at best a reassuring sideshow, an attempt to fool people into thinking nuclear war was survivable. At worst, it was warmongering: if you think you can live through nuclear war, maybe you will wage it.

The Civil Defense critics won out; Duck and Cover and city evacuation plans were just too easy to take potshots at. Faced with rapidly diminishing support, the drills stopped in the late 1980s. The Federal Emergency Management Agency, the successor to the FCDA, concentrated its efforts on natural disasters. When the Obama Administration looked into creating nuclear-terrorism guidelines for civilians in 2010, they were met with skepticism and snarky references to Bert the Turtle’s smug paternalism. And so schoolchildren still train for earthquakes, tornadoes, and active shooters, while nuclear matters have dropped off the radar.

But perhaps we’ve underappreciated the value of the Cold War mind-set nurtured by Civil Defense. Throughout much of the period, Americans felt that the risk of nuclear war was, as political psychologists would say, salient. This means that even if we can’t see a risk directly and with our own eyes, we believe in the danger intuitively and allow that belief to drive both our everyday behavior and our political positions. In the case of nuclear weapons, the actual, physical bombs were generally out of sight, hidden by military secrecy, but they were never out of mind. Nuclear war could happen at any moment, and many felt that it would happen, potentially in their lifetime. In 1983, some 24 percent of Americans identified, without being prompted, nuclear war as the most important problem facing the country — more important than the economy, unemployment, crime, or morality. The generation that Bert taught to hide from the bomb was a generation that took nuclear risks seriously.

Stills from Duck and Cover. Courtesy Prelinger Archives/Archive.org

Today, it is hard to imagine a world in which Americans thought nuclear war was more pressing than crime, despite the fact that the crime rate has been steadily declining and the risks of nuclear war seem to be rising. Brinkmanship on the Korean Peninsula brings these issues to the front pages and induces momentary concern, but it is quickly subsumed by other controversies and fears in our ever-changing news cycle of horrors.

Consequently, we no longer have any sense of nuclear salience — no sense of nuclear risks being real. The message of Duck and Cover, after all, was only partially about hiding under a desk: most of it was about orienting one’s mind to the idea that nuclear detonations are a part of the world in which we live, like car accidents, influenza, and muggings.

It’s worth wondering, then, what we could get out of a reinvention of Civil Defense in the twenty-first century. If the American public had a sustained and realistic sense of nuclear risks, and the policies and choices that could exacerbate or ameliorate them, what might be possible? The proposal is one that Americans of all political stripes, and all positions on nuclear weapons, would be able to embrace. If you think sensible Civil Defense measures could save lives in the event of a nuclear attack, then that prospect alone might make it seem worth pursuing. If, on the other hand, you think Civil Defense is worthless as a safety measure, you might still value a renewed focus on nuclear threats, which could revitalize efforts to reduce their risk.

The trick, as always, would be in the doing. How would such a strategy avoid polarization, partisanship, and the evils of alarmism and complacency? How, when trust in government has been waning for decades, should such messaging be handled, and through what media? The goal, in the end, must be to banish the apparent absurdity of Bert the Turtle while restoring the sense of lingering existential danger that lurked just outside his shell.