Discussed in this essay:

The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick, edited by Darryl Pinckney. NYRB Classics. 640 pages. $19.95.

Elizabeth Hardwick was drawn to the stifled shriek of the psyche in a world ruled by force. She saw how force works: how it stomps, cuts, beats, kills — and coddles, tickles, dances, flirts, holding out its bitter pleasures and dreary consolations to the striving, the deluded, and the weak. “The weak have the purest sense of history,” she once wrote. “Anything can happen.” But Hardwick is merely remembered, when she’s remembered, as a stylist, a glamorous irrelevance fashioning her slanted prose. It’s a tempting image; the prose is luminous. Novels, stories, reportage, criticism — every Hardwick artifact is instantly distinguished by her insistence on elaborate syntax, her sentences pitted with controlled eccentricities and sly blurs of phrasing. An unnamed South American writer strides into an essay from 1963:

His fingernails and his careful, neat dress tell you of all the polish, the care, the melancholy mending done at home by mothers and sisters. This man was one of those whom struggle had drained dry. He had arrived, by hideously hard work, at an overwhelming pedantry, a bachelorish violence of self-control. The pedantry of scarcity.

“The pedantry of scarcity”: the phrase is clipped but elliptical; the abstractions startle when juxtaposed. But what is the “violence” here, which taints the spirit and stalks its “self-control”?

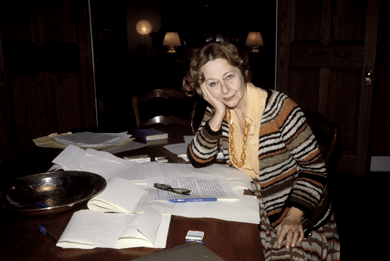

Photograph of Elizabeth Hardwick by Inge Morath

© The Inge Morath Foundation/Magnum Photos

It’s all like this: sentences swiveling to probe and devour themselves, reveling in the bleary astonishment of experience. The first page of Sleepless Nights, Hardwick’s last, best, and most autobiographical novel, calmly presents its task as “this work of transformed and even distorted memory” — and the final page proclaims that this distortion, the act of pitching life into prose, packs a hazardous thrill: “Sweet to be pierced by daggers at the end of paragraphs.”

Many have been pierced. Wayne Koestenbaum’s collection My 1980s contains an essay titled “Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sentences,” and Brian Dillon has written a brilliantly sensitive study of a single one. Susan Sontag pronounced her the “queen of adjectives” — a salute to how Hardwick’s modifiers grip and twist their referents to release some flashing trickle of implication: “bachelorish violence,” “melancholy mending.” This is the stuff of fact, thought, sensation, arguments grinningly disciplined by style.

A new volume, The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick, augments her reputation by proving what that style could do: not simply assess literary texts or narrate the story of the self but grasp the relentlessness of collective existence. We see her charge at the world, armed with the perspicuity and compassion of her analysis, arriving at insights that together make up a mural of her age. Literary reputations are established and revised: Hardwick is a deft interpreter of letters and memoirs, listening closely for what’s muzzled, masked, deferred. (She thinks that Hart Crane may actually have lived quite happily! And that Byron’s lovers are “afflicted with the wrinkles of class arrogance.”) Jagged ruptures in culture — like the sexual revolution — are scrupulously judged: “The body, the young one at least, is a class moving into the forefront of history.” Civil rights, Vietnam, the new left, and second-wave feminism rumble through the book like tanks.

Ten years after her death, this book brings together literary commentary, reporting, and social criticism — often for The New York Review of Books, which she helped found in 1963 — to place Hardwick not simply in her clique or her generation but in her world: the tense, slashing, insurgent world of postwar American arrogance and crisis.

She came from the South. Born to a large Kentucky family in 1916, “Lizzie” was the daughter of a Lexington plumbing contractor. After completing her undergraduate degree at the state university, she enrolled in — and dropped out of — graduate school at Columbia. New York pleased her. With just a few interruptions, she lived there for the rest of her life, allowing Kentucky to recline into the distant, wistful past. The young heroine of an early short story, “Evenings at Home,” from 1948, visits her family down South and notes how even the warmth and solidity of her old world grates against the fantasy of the literary life: “It is awful to be faced each day with love that is neither too great nor too small . . . each smile is a challenge, each friendly gesture an intellectual crisis.”

Better to be striking and severe. Hardwick installed herself boldly among the New York Intellectuals, a largely Jewish group of writers preoccupied by modernism and riveted by politics. The Family, as the group was sometimes called, was a pit of erudite vipers, many of the members lapsed Marxists who snapped into a compulsory anticommunism at the start of the Cold War. The journal Partisan Review provided the perfect stage for their postures and disputes: in its pages Philip Rahv, Irving Howe, Edmund Wilson, Hannah Arendt, and Lionel Trilling sharpened their reputations as critics and polemicists, gong-banging arbiters of literature and the left.

Among them Hardwick was considered a pretty, gentile sophisticate with a taste for le mot juste. But as a literary critic she proved herself a master of articulate contempt. “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” her 1959 essay for this magazine, would come to serve as a sort of declaration of independence for The New York Review of Books. The whole literary press, waddling behind The New York Times Book Review, had allowed criticism to grow polite and “listless,” and that listlessness, to Hardwick, was a crime: “Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns.” Books themselves, no longer written about with rigor, were fated for their own decline. The whole arrangement was successful only in “denying whatever vivacious interest there might be in books or literary matters generally” as the culture slouched toward banality.

Hardwick’s approach to the literary essay has a charming particularity. On the page, she’s less an exegete than a portraitist, lavishing attention on the writer’s suffering, attitudes, environs, and fate. Origins obsess her, as do landscapes: literature, especially American literature, matters because it’s part of the unfolding experiment of a specific place, in a specific time — with its ironies and cruelties.

“America and Dylan Thomas,” an essay from 1956, presents the poet as a British tchotchke, praised for his genius and fetishized for his demons. He is portrayed as a rude, brilliant, womanizing alcoholic. In the end, “his drinking had made him, at least superficially, as available as a man running for office.” A sick romance attends his final years, as American audiences lap up his “fabulous difficulty” and, “sinking sensuously into their own suspicious pity, flattered and allowed and encouraged right to the brink of the grave.” Thomas in America was a poète maudit, martyred by our cynical love.

Loss transfixed her. In her criticism, Hardwick displays a fondness for elegy, so that even at her most cutting or incorrigible there is a tender appreciation of the ambivalences and compromises that plow through human life. The role of literature seemed to be to slow down the pain, to pore over it in a kind of wise, excruciating delectation. George Eliot once described Macbeth as a play that pits the “clumsy necessities of action” against the “subtler possibilities of feeling” — a battle Hardwick wages with conviction in her work. Fitting, then, that Eliot, with her moral patience and rolling, virtuous sentences, is given the most sensitive portrayal in this collection:

She was melancholy, headachy, with a slow, disciplined, hard-won, aching genius that bore down upon her with a wondrous and exhausting force, like a great love affair in middle age.

But that genius wasn’t enough for her peers: she was considered dowdy and provincial, pitifully incapable of glamour. In assessing the attitudes of contemporaries such as Leslie Stephen and Edmund Gosse, Hardwick lands on a word that conveys the weakest, dreariest, most grudging kind of admiration: “respect.”

How, Hardwick wants to know, does a person freeze into a persona? And what, precisely, is the relation between the inner torment and the public self? Her studies of writers — both her predecessors and her contemporaries — confront the question of reputation, of celebrity: that is, of the place and purpose of the writer in the world. For all his private suffering, Robert Frost was marked by “the clamorous serenity of his old age,” his aura of bucolic wonder. Nathanael West, who after his death enjoyed “an impressive stream of recognition,” was so in love with his failures that he put the “critics in the position of a crusading doctor reviving the moribund.” Whereas Sherwood Anderson “brought to literature almost nothing except his own lacerated feelings,” Henry James wrote removed, stately works of fiction that “do not have the atmosphere of autobiography, do not hint at the author’s life.” This is a disappointment. James’s novels, replete with ornate effects and sparkling refinement, are cast as extended exercises in detachment, “a bachelor’s cool eye on the common sentiments.”

His foil is Philip Roth. Hardwick sees Roth’s raging flourishes in novel after novel as a boyish need to broadcast his assaults on convention. Sex, for him, has been ripped away from love, becoming “a penitential workout on the page with no thought of backaches, chafings, or phallic fatigue.” But Hardwick is wry in the face of all this naughtiness. She finds Roth’s jarring American Pastoral to be “rated PG,” nostalgic as it is for an idyllic vision of family. The book isn’t a flaming prediction of our brave new world but a tender tribute to a vanished one. Her review is titled “Paradise Lost.”

That slicing acuity would serve Hardwick well in Cold War America. It was a time full, somehow, of both euphemism and hyperbole. She was a twitchingly attentive reader of manipulative foolishness — or “public discourse” — and many of her essays cock their head at the latest abuse of language.

In 1965, the riots that followed the beating of a black motorist by the Los Angeles police inspired a muddled official report released by something called the Governor’s Commission on the Los Angeles Riots with the title Violence in the City: An End or a Beginning? Hardwick’s “After Watts” ran in the New York Review in 1966, and was indeed presented as a review. So the report was subjected to Hardwick’s appraisal, her fastidious ear for technique and effect:

Still, the Watts Report is a mirror: the distance its bureaucratic language puts between us and the Negro is the reflection of reality. The demands of those days and nights on the streets, the smoke and the flames, are simply not to be taken in. The most radical re-organization of our lives could hardly satisfy them, and there seems to be neither the wish nor the will to make the effort. The words swell as purpose shrinks.

Of all the New York Intellectuals, Hardwick wrote most convincingly, with the most affecting effort, about the black struggle. To the state’s rubber-stamped paragraphs she replied with a rattling portrait of LA and its history. Those “days and nights of the Watts community,” paved over by the city’s official prose, are returned to us as Hardwick invokes the dislocations of the Great Migration: “Alabama and California are separated by more than miles of painted desert.” A picture emerges of a black communal life, wiped of dignity or self-understanding (if one can separate the two), left to melt in the smeared desolation of Los Angeles. Within that shapelessness, shape had to be made: “The Watts riots were a way to enter history, to create a past, to give form by destruction.”

Revolt, then, devolves to a question of aesthetics — of the hunger for “form.” This is not trivial. The form, in Watts, was rage; only through rebellion could people achieve greater comprehension of who and what they were. Hardwick sees Watts as a wish to act on the world, a world stuffed with stony, indisputable facts — but also glimmering, shifting, draped with feeling. Hardwick’s melancholy acceptance of feeling’s sublime, electrifying force makes her political writings sing. She understands history as the story of how people relate to their lot: they lunge, full of desire, at the silhouette of an imagined world.

But politics is a narrative like any other, demanding its symmetries and settings and soaring, gripping themes. Sometimes the narrative is so turgid, so throbbing with significance, as to be uncanny — as in Memphis after the murder, but before the funeral, of Martin Luther King Jr.:

The deranging curfew and that state of civic existence called “tension” made the town seem to be sinister, again very much like a film set, perhaps for a television drama, of breakdown, catastrophe. Since films and television have staged everything imaginable before it happens, a true event, taking place in the real world, brings to mind the landscape of films. There is no meaning in this beyond description and real life only looks like a fabrication and does not feel so.

“The Apotheosis of Martin Luther King,” from 1968, recorded the taut posture of a city as it was hit by the exigencies of its moment. But Hardwick also captured how the civil rights movement was an address to and a development of antagonisms lodged so deep in the South that they came to feel rehearsed, almost hokey. From “Selma, Alabama: The Charms of Goodness,” published in 1965: “Life arranges itself for you here in Selma in the most conventional tableaux. . . . The ‘crisis’ reduces the landscape to genre.”

Looking on this stage set, however, Hardwick isn’t content to smugly appraise the actors, because she counts herself among them. She was born in the South and had observed the dark satisfactions of upholding “tradition.” (“Look at the voting records,” the narrator tells us in Sleepless Nights, “inherited like flat feet.”) In Selma, a young man — white, poor — tells her outside the courthouse that the sight of whites mixing with blacks makes him sick. Hardwick recognizes in him and his comrades a kind of sociological inevitability and a gaping psychic hole: “This group of Southerners has only the nothingness of racist preoccupation, the burning incoherence.” Grasping for a response, she realizes that there’s nothing to say — suggest a social worker, a therapist, a doctor? — but she manages to tell him, softly: “Pull yourself together.”

The moment is at once gentle and abrupt. The voice that narrates the essay, a voice that has thus far been boldly unfurling its idiosyncrasies and intelligence, is yanked back, shuddering, into the heat and fear of the encounter. Made to speak, Hardwick is crushed in that moment by what she’s forced to see: that the boy is a symbol and a person, a psyche and a political actor. She is not sure what she owes him. So her voice, challenged by the impossible synthesis, goes soft — while trying, in its righteous way, to correct.

The bracing little riposte was a staple of the women of the Family. They all seemed to glitter with a puckish strength which may have helped them to weather the swirling explosions of marriage. Edmund Wilson punched and kicked Mary McCarthy while she was pregnant, Diana Trilling was tormented by Lionel’s psychotic fits, and a few of Robert Lowell’s howling manias climaxed with his removal to a mental ward, where he languished in a muddled, gloomy exile. Hardwick brought him his books.

Their first encounter, at Yaddo in 1949, vibrated with sexual magnetism. Lowell was already a celebrated poet, and Hardwick had published her first novel, The Ghostly Lover, four years earlier. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” she later said, “but even if I had, I still would have married him.” Though she was trailed by the faint suspicion of social calculation — Lowell was a Boston aristocrat — her devotion to him was total, even self-mutilating in its tenacity. Once, after a flash of violence, she reminded him delicately that “other men don’t hit their wives.” He repaid her sacrifice with erratic, intense affection and stretches of addled infidelity. He was trapped in his illness — and indulged, constantly, for his mind.

She was humiliated when he abandoned her after twenty-one years. He’d fallen for the British writer Caroline Blackwood and left to join her in London, a desertion that provoked livid, ravaged letters from Hardwick, which Lowell promptly deposited — with a few cruel alterations — in The Dolphin, the book of poems that won him his second Pulitzer Prize and nearly broke her will to live. She’d been unable to write for long periods in their marriage, but in 1974 she put out a book of essays with a title of searing potency — Seduction and Betrayal: Women and Literature. In 1977, after seven years, Lowell came back to her, and they passed a summer together in Maine. He flew to London to retrieve a few of his things, and in the taxi back to their apartment in New York, he suffered a heart attack and died.

“Sometimes I resent the glossary, the concordance of truth, many have about my real life, have like an extra pair of spectacles,” confesses the narrator, also named Elizabeth, at the end of Sleepless Nights, which was published two years after Lowell’s death. Peer through those spectacles and Hardwick is flattened into facile tragedy, a victim padlocked to a madman. Reach for a different pair — as the Partisan Review editor William Phillips must have when he assessed her in his memoirs — and she’s merely “articulate, witty, very clever.” The words are light, pricking insects, extracting their drops of blood. It’s true that Hardwick could be mordant, effervescent, chic — and was fond, especially in her essays, of the dark cackle and the ironizing sigh. (On the radical milieu of New York in the Thirties: “Trotskyite and Stalinist — part of one’s descriptive vocabulary, like blue-eyed.”) But beneath the “shimmering of intelligence” (Lowell’s phrase) was a ferocious sympathy, a mournful pledge to witness — to log, translate, dignify — the lavish profusion of human pain justified as politics, asserted as necessity, or sweetened as love. Hence her prose’s strange embellishments and stunning kinks: quirks of style that capture the collision between what we know and what we want.

Wants — personal and collective — would supply the second half of the twentieth century with its most violent social convulsions. Hardwick’s reported pieces from Selma and Los Angeles hang in loose conformity with a trope of the Sixties and Seventies: the white, alluringly female intellectual who slings her sensibility over her shoulder and strikes out in search of chaos — preferably a revolution. The result is a sophisticated frisson as urbanity duels with the weltgeist. Think of McCarthy in Vietnam, Sontag in Vietnam, Joan Didion in Haight-Ashbury, Renata Adler in Vietnam, Adler in Israel, Adler in Nigeria, Adler in Selma. Hardwick would turn her critical attention to the work of these women with appreciation and discernment, advocating stoutly for the novels of Didion and Adler. Drift rules their books, books that track heroines full of trembling intellect — Adler’s narrator in Speedboat is “a lucky eye gazing out from a center of a complicated privilege” — as they take inventory of experience and its scrambled contents.

Scrambled, in part, by their sex. Hardwick would eventually become a champion of women writers, though only with a calculated abdication from anything so boorish as a “position.” In 1953, she’d written an imperious review of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex for Partisan Review. It was a piece full of baffling, telling weaknesses. Hardwick appears as a resistant analysand squirming on the couch: with a dismissive chortle she rejects as contradictory each of de Beauvoir’s arguments, as if contradiction weren’t de Beauvoir’s point. The book didn’t just irritate Hardwick; it jerked and disturbed her. She saw the problems of women as real — and insoluble. Much of what she had lived through and observed had taught her that even the gentlest relations between man and woman were shot through with a compulsive brutality: “Any woman who has ever had her wrist twisted by a man recognizes a fact of nature as humbling as a cyclone to a frail tree branch.”

She takes special exception to de Beauvoir’s claim that women writers have been restrained by men: only “the whimsical, cantankerous, the eccentric critic” could possibly claim that any literature by a woman rivaled the towering achievements of the masculine genius. Arguments stream through the essay, some cleverly rendered but all tethered to the conviction that women’s biological nature, their supposedly inborn reserve, is a final, immutable block. Hardwick’s taste for tragedy coarsens into fatalism.

Decades later, she recanted. “It’s a wonderful, remarkable book,” Hardwick told the writer Darryl Pinckney, who edited this collection, in an interview for The Paris Review in 1985. Hardwick’s supple political sense had been bringing her closer to the women’s movement. In the Seventies she had embarked on that most valiantly feminist task — recuperation! — by editing a series of neglected books by Constance Fenimore Woolson, Evelyn Scott, Ellen Glasgow, Frances Newman, and Mary Austin, works wheeled back into print “with a new introduction by Elizabeth Hardwick.” But she always shrank from militancy. Seduction and Betrayal, stamped by the pressures of Seventies feminism, wriggles out of ideological lockstep to lightly recuse the author from the postures struck by a new, blistering movement. Its heroism — its fuming break with the past — was too gruff and total for the aging woman of letters.

The book addressed the desires of and assaults on women in literary history. Ibsen’s heroines are given their own section. Then there are the wives and sisters relegated to literary obscurity — Dorothy Wordsworth, Jane Carlyle, Zelda Fitzgerald — as well as the imperious “lady writers” of the canon: the Brontës, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath. (The last had been Lowell’s student.) However exquisite, the essays are marked, at times, by Hardwick’s smirking reluctance to read with one eye fixed on liberation. Plath’s womanhood might explain “the exceptional rasp of her nature,” but so, perhaps, could her “special lack of national or local roots.” While Dorothy Wordsworth’s unbreakable attachment to her brother’s nuclear family “cannot be wholly endorsed by contemporary women critics or by female readers given to skeptical wonderings about arrangements and destinies,” Hardwick saw it differently. It was “a kind of conquest; lucky, safe, and interesting.” Though Hardwick saw the need, finally, for feminism, she refused to pledge allegiance to a need.

Needs hurt. Sleepless Nights, with its swells of feeling, chains that hurt to history. The novel, published when Hardwick was in her sixties, casts a clarifying light on the essays, as the fiction goes further into the mind that made the prose. Sleepless Nights attempts, with delicate lapses, to tell the story of “Elizabeth”: her blue-collar beginnings in Lexington; her distant, pretty mother; and her brief dalliance with the Communist Party before her escape to literary New York.

But the novel flies beyond Hardwick’s particular life to relay the fates of those who touch her: people groping at their comforts but strapped to their defeats, defeats that correspond, with punitive exactitude, to their place in the world. A pompous radical is discarded by his benefactress. A mother is punished for her devotion. A Holocaust survivor is helpless in love. Billie Holiday — with whom Hardwick, fresh from Kentucky, had a few strange, radiant encounters — is shown being swallowed by the excesses that she rapturously poured into art. The poor of Kentucky dream, with desperate justification and life-regulating passion, of a socialist future, “under the quilts and under a blanket of papers, as if the old Daily Workers could give the body warmth, like rags.”

History bursts in savagely, crashing into the psychic furniture, and you realize that the lapidary Hardwick, Hardwick the wit, Hardwick the idiosyncratic critic and long-suffering wife, are mere facets on the diamond. She strove, quietly, to deploy a political conscience, to remain a woman in thrall to the wrenching, poignant relations between things, someone sensitive to sharp reversals and delicate rearrangements — sensitive, that is, to style.

A whole chapter of Sleepless Nights is given to working-class women who scrub, cook, serve, age. In many ways, it is a book about the poor.

When I think of cleaning women with unfair diseases I think of you, Josette. When I must iron or use a heavy pot for cooking, I think of you, Ida. When I think of deafness, heart disease, and languages I cannot speak, I think of you, Angela.

I hear murmurs of Selma, of feminism, of revolution; I hear the sighs of Dorothy Wordsworth and the ragged screams of Watts. People thrashed by circumstance and fleeced by systems are the muses of Hardwick’s novel of depletion. She wanted to call it The Cost of Living.