Discussed in this essay:

Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers by Elaine Mokhtefi. Verso. 256 pages. $24.95.

He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art by Christian Wiman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 128 pages. $23.

Deviation by Luce D’Eramo, translated by Anne Milano Appel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 368 pages. $27.

What does it take for an individual to make a difference in the world? Given the state of things, the question might seem too paralyzing to ask. At the beginning of her memoir Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers (Verso, $24.95), Elaine Mokhtefi (née Klein) seems to be just another carefree young American in postwar France, enjoying the beaches and tagines and pastis, attending sex shows and dance parties known as pince-fesses (“ass pinchers”). But her interest in politics is already clear—she was the head of the student wing of the United World Federalists (before the students got thrown out of the organization for being too far to the left). During her tenure she was so vociferously anti-racist that the FBI showed up in her hometown asking questions. Political action seems a fairly natural and straightforward part of life for her. As she gradually picks up more work as a translator and interpreter, she gets involved in the struggle to end France’s brutal colonial war in Algeria: returning to the United States, she spends a few years campaigning for the cause from an apartment near the UN before moving, once independence is won in 1962, to Algiers, where she finds work serving the new administration.

Independence Day, Algiers, July 5, 1962 © Marc Riboud/Magnum Photos.

Mokhtefi attracts quite the cast of characters. Early on, she receives some sensible dating advice from none other than Frantz Fanon: “Non, non, non,” he insists when she admits she is looking for someone on whose shoulder she can rest her head. “Stay upright on your own two feet and keep moving forward to goals of your own.” She finds more such encounters in Algiers, which, she writes, extended an open invitation in the Sixties to “liberation and opposition movements and personalities from around the world.” There she meets Palestinian activists, members of the Vietcong, African National Congress leaders, Latin American guerrilla fighters, and amateur hijackers who touch down with bags bulging with ransom money. Mokhtefi appears as an extra in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers and then, walking down eerily quiet streets one morning a few weeks later, wonders at first whether the crew is somehow still filming before realizing that there has been a military coup. Adept at solving problems and cleaning up messes, Mokhtefi is seen wrangling a drunk Nina Simone into performing her scheduled set at a Pan-African cultural festival, or flying Stokely Carmichael’s American girlfriend to see him in Guinea and then consoling the poor thing after he abruptly dumps her for the singer Miriam Makeba.

Most memorable, though, is Eldridge Cleaver, the Black Panther Party’s leading spokesman and the author of the prison memoir Soul on Ice, who finds his way to Algeria once exiled from the United States after a 1968 shootout between Panthers and police. Mokhtefi loans him her car and apartment, translates for him, helps the Panthers gain recognition as a legitimate liberation movement and eventually arranges fake passports to get the remaining Panthers out of Algeria when Cleaver’s relations with the regime turn sour. No matter how doomed the project, she’ll give it a go, even when Cleaver tries to persuade visiting prison escapee Timothy Leary, in the name of revolution, to rein in his ego, “discipline himself and renounce drugs.” (“A tall order,” she notes, nonetheless dutifully smoothing the way for Leary with Algerian officials and ensuring that his antics don’t threaten the Panthers’ status.) After Cleaver’s Algerian branch of the Panthers acrimoniously splits from Huey Newton’s party in 1971, she tries to raise money for them. She seeks comradely assistance from Simone de Beauvoir and from Jean-Luc Godard, who sniffily refuses while referring to himself in the third person.

Mokhtefi handles some spectacular material in brisk, modest fashion. The inevitable doubts and conflicts that arise are not agonized over. Mokhtefi “despises” Cleaver’s propensity for rape, domestic violence, and murder, but she seems never to consider giving up her efforts to help out with his nobler pursuits. When Cleaver informs her that he’s just killed a fellow Panther (Clinton Smith, who, it turned out, had been sleeping with Cleaver’s wife), Mokhtefi freezes in horror and anger, but is back to making arrangements for him with her Algerian contacts by the next page. Her feelings and motives remain just slightly out of frame. She seems amused and irritated by the extravagant creativity of Cleaver’s self-presentation in his 1978 book Soul on Fire, in which he claims to have kept himself afloat in Algeria via a series of glamorous rackets, like selling stolen cars. She gently lets the air out of this idea, noting that in fact the need for “wheels” was a constant difficulty for the Panthers, who mostly made do with a used van and a donated minibus.

Mokhtefi focuses less on how her political allegiances developed, what she was or wasn’t willing to do and why, than on telling, in lively, lucid fashion, what happened and who did what. To do otherwise might have produced a longer and in some ways more substantial book. But it also seems possible that this readiness to minimize herself on the page is related to whatever capacity allows a person, over the years, to participate in politics, navigating the compromises involved. Some decisions—like refusing to spy on a friend at the request of the Sécurité Militaire even though it will eventually mean leaving Algeria for good—are easier than others: much as Mokhtefi loathes Cleaver’s treatment of his wife, Kathleen, she stays focused on the larger political goal all three of them share; feminist liberation is subordinated to other kinds, and many readers may wish Mokhtefi’s reasons for accepting this could have been more thoroughly explored. The story of how she became who she is she leaves for a literal afterthought, a short concluding chapter called “An American Childhood.” Here she makes clear that all this restraint has been hard won: earlier in her radical awakening she recalls of herself and her comrades that “we were part of the struggle for a better world. We were also insufferable, convinced we had received the ‘word’ and were anointed to spread it. Of course, we never shut up.”

Apainter and longtime journalist used to being denied a byline, Mokhtefi is not much preoccupied with her own role as a writer. Hers is a life shaped by her political sympathies, which were expressed in as practical a way as she could manage. The poet and divinity scholar Christian Wiman would seem to occupy the other end of a spectrum in He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $23), a rumination on what drives and justifies writing. Like Mokhtefi’s, his slim book is crammed with encounters with those better known than he is, and he can be similarly wry about them, as in the memory, from his time as the editor of Poetry magazine, of making a mild critique of Wallace Stevens’s late abstraction and then being dismissed as “a dinosaur” and handed “my hegemonic ass” by the poet Susan Howe before an audience of enraged Stevens fans.

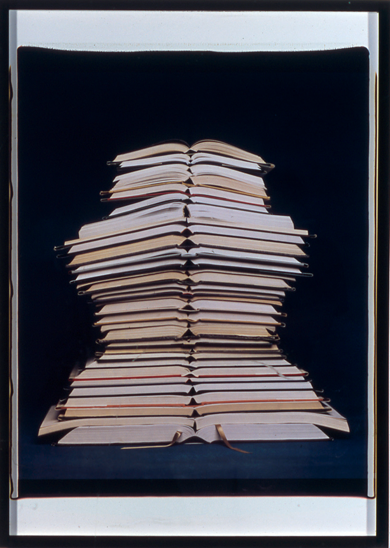

“Spine #2,” by Buzz Spector © The artist. Courtesy Bruno David Gallery, St. Louis

While continuing the discussion of existential and religious questions he addressed in earlier books, such as My Bright Abyss, in this latest work Wiman considers some of the central problems of a life dedicated to poetry—how the work must reach out toward something beyond it, and how one must nonetheless take the work seriously as an end in itself in order to produce any writing worth a damn. He considers the tortures of the ego—the young writers who “writhe on the high hook” of frustrated ambition, the older ones wrestling with the horror of imminent oblivion. And he suggests, with Robert Frost, that the way out of these dilemmas is “always through,” that real artistic ambitions can replace the lowlier kind, and that these real ambitions have perforce a link to something higher.

For Wiman the connection between divinity and poetry has been inescapable. Having moved away from the faith of his childhood, “transferring that entire searching intensity onto literature” before reacknowledging God, he now appears to have reached a synthesis. He cites good-humoredly in He Held Radical Light the man who, after Wiman’s lecture “Poetry and/as Faith” (a theme echoed by the subtitle of this book), inquired as to why he didn’t “just go ahead and drop the ‘and.’ ” Wiman writes that poetry may offer its serious practitioners a saving humility—an encounter with inevitable failure and finitude, and with something that can be known only imperfectly, in flashes.

If writers are striving for something beyond what they’re literally working on, Wiman wonders what that something could be—God? Death? There’s another possibility, the yearning for a more concrete ethical engagement with other people, of the kind Mokhtefi attempted—and it is, intriguingly, one he barely considers. The spiritually inflected reaching-outward he recommends—love for poet friends, his wife, his daughters, to whom his study door is nowadays “always open”; the work of the oncologist who treated his cancer—never exceeds the bounds of private life. He declares at one point that “promiscuous sympathy is pointless and damaging for all concerned,” identifying the fundamentally self-directed “shiver of pleasure-horror that goes through your spine when you read about someone else’s suffering” and insisting on the difference between that and a true caring impulse. You’re making a grave error, he suggests, if you

mistake this reaction for action; if you confuse this shadow sympathy for the kind of real feeling that operates in the world with risk and agency and perhaps even grows cold to survive . . . if you mistake love of literature for love.

It may be that this sharp distinction between life and literature makes more sense for casual readers than for writers. Wiman recalls once using the metaphor of form as “a diving bell in which the poet descends into an element that would otherwise destroy him,” noting the concomitant risk that “one’s forms might become merely protective and not expressive.” Luce D’Eramo’s extraordinary novel Deviation (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27), a bestseller in Italy when published in 1979 but only now available in English, in a translation by Anne Milano Appel, is, as its title may imply, a rejection of the idea that literary form can be neatly separated from psychic and political life. Autobiographical without ever being simply or transparently so, the story is so eventful that it initially threatens to make the style of its telling invisible—the content upstaging the form—when in fact the drama and difficulty of that telling will become central to the book.

It’s no mean feat even to summarize the novel’s plot, which emerges in uneven, nonchronological, tonally disparate sections, written at different times and dated as such, their edges left jagged, the elisions and distortions of earlier parts revisited and highlighted in later ones. The story begins with the narrator’s escape from a concentration camp at Dachau in October 1944 and her time in a nearby transit camp, then skips to the moment the following year when, trying to rescue people from the rubble of a bombed building in Mainz, she is crushed by a falling wall and paralyzed. The book then jumps backward in time and slides into the third person as it describes “Lucia’s” arrival in the Third Reich from Italy and her experiences in a labor camp there, working for the chemical division of IG Farben. The fourth part, “The Deviation,” narrates some of her later life—her marriage and child, the travails of navigating her disability—while also returning to the stories told earlier, analyzing what she remembered when, and why. Like the author herself, D’Eramo’s protagonist, it gradually emerges, grew up in a comfortable family of Italian Fascists and ran away at age eighteen to a labor camp in Nazi Germany as a volunteer, in an effort to confirm for herself that the whispers about such places were untrue. But there she experienced a political awakening, tried to organize a strike, and renounced her social class and family connections, ditching her documents and voluntarily allowing herself to be sent to Dachau—an incident she misrepresented for many years as an involuntary deportation.

The change in perspective she experiences in the labor camp colors everything that comes after it. Even in Dachau she sees how much money and class matter. The camp begins to strike her as “not another reality but merely an extreme form of the same order that existed outside,” and likewise, she recognizes after the war, when the political tides turn, how profoundly a person’s class background continues to affect her fate.

A novel is the classic form through which to convey a drastic shift in individual consciousness. By dramatizing its own struggle to be written, this one displays the process of changing your mind and trying to take responsibility for yourself and your place in the world. D’Eramo’s narrator untangles the ways in which, even as she believed herself to be embracing a new solidarity with those around her in the camps, she inwardly held herself apart, often falling back on her old advantages. She notes how, in the concentration camp and afterward, she kept sliding into her old mind-set, in which “everything was a question of courage, of individual morality: of responding with the truths of one’s own convictions,” and that this was an individualism the camps encouraged by design—“the concentration camp managed to achieve its real purpose: to destroy the social conscience of the internees.” She keeps shedding her bourgeois skin but it always regrows, protecting her from what others must suffer, trapping her by turns in self-serving and self-punishing delusions.

She is aware of the way her memory continually alters the past and especially the self that occupied it. The book’s vividly drawn early sections are presented as memories long repressed that D’Eramo’s narrator accessed and recorded in a rush during brief periods in the mid-Fifties, when her marriage was collapsing, and the early Sixties, when she found herself in a home for the disabled. Yet they are also revealed as highly artificial reconstructions that must be painfully torn down and reassembled to find what has been left out.

How such a story is written can only be a purely aesthetic question, rather than an ethical one, if you believe it’s possible to live first and write afterward. For the most part, though, there’s no tranquility from which to recollect your life: you narrate yourself as you go along, and it affects what action you take. Elaine Mokhtefi notes in passing in her opening chapter that she had a certain advantage over her friends in Paris, being freer to invent herself abroad, whereas their work and education had been “codified by class,” their lives “carved out in advance.” Since she was able, as she saw it, to decide her own course, it may be easier for her to tell it back as simply as she now does. D’Eramo, on the other hand, must put herself and where she comes from at the heart of what’s examined—the cloudiness of the lens is an essential part of what she has to show.