Discussed in this essay:

All That Heaven Allows, by Mark Griffin. Harper. 496 pages. $28.99.

Turned On: Science, Sex, and Robots, by Kate Devlin. Bloomsbury Sigma. 288 pages. $27.

In Our Mad and Furious City, by Guy Gunaratne. MCD x FSG Originals. 288 pages. $16.

At dinner in San Francisco’s Tenderloin in 1976, the writer Armistead Maupin urged Rock Hudson, the twentieth century’s most famously closeted heartthrob, to come out by writing a book. Hudson’s longtime lover, Tom Clark, allegedly protested: “Not until my mother dies.” “I remember thinking,” Maupin recalls, “If I were fucking Rock Hudson, I would have no problem at all telling my mother.” It’s the best line in Mark Griffin’s new biography of Hudson, All That Heaven Allows (Harper, $28.99), and it also neatly sums up the way in which Hudson—known or suspected by many around him to be gay—nevertheless occupied a position as an ideal all-American object of desire, a man so unimpeachably manly that even coming out might not have been enough to ruin the effect.

Hudson’s double life is only one of the classic Hollywood ingredients in his story. There’s the father who walked out one day when Hudson was five (apparently he paid a niece a nickel not to tell anyone he was leaving) and showed up again only when he needed his world-famous son to clear his gambling debts. There’s the poverty; the drunk, violent, pointedly hostile stepfather; the needy mother with whom young Roy Scherer (Hudson’s birth name)took refuge in Saturday matinees. And then there’s the sleazy agent, Henry Willson, whom Roddy McDowall described as “like the slime that oozed out from under a rock you did not want to turn over.” An infamous “manizer,” Willson bedded his six-foot-four client, gave him his campily hypermasculine stage name—the Rock of Gibraltar crashing into the Hudson River—and eradicated all perceptible traces of what Griffin calls Hudson’s “inner sissy.”

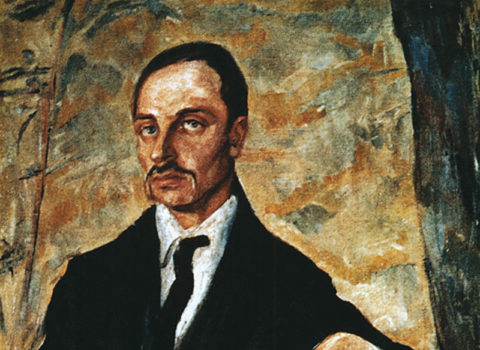

Rock Hudson on the set of Giant © Frank Worth/Capital Art/Getty Images

Like other tales of old Hollywood, this one is full of tantalizing nuggets. What did Hudson talk about with Marilyn Monroe or Judy Garland, both of whom used to weep down the phone to him late at night in the early 1960s, or with Jennifer Jones, of whom he said, on hearing of the death of her husband, David O. Selznick, “What a relief it must be for Jennifer”? The book also has its moments of unease. It’s fair to say that Hudson’s pickup techniques might not pass muster today: he generally chose what Griffin calls a “playmate” to take on location, and boys who didn’t cooperate didn’t get cast. “If you don’t leave early,” a friend remarked of Hudson’s parties, “it probably means you’re an unemployed actor.” At the time, his acquaintances’ reactions to his sex life were mixed—and unpredictable. Whereas Lauren Bacall was shocked to hear of his antics, John Wayne didn’t bat an eye when Hudson “took a member of the Los Angeles Rams to bed with him” at the end of a day’s shooting: “I think Rock’s a hell of a guy,” he said. “Who the hell cares if he’s queer? The man plays great chess.”

Hudson’s taste for jocks, in fact, would seem to be one of the more unimaginative things about him. The book implies that no ripped, lantern-jawed blond escaped his attention, a convenient predilection at least in the sense that such men were easy to cast in B movies whenever they needed to be dissuaded from selling their stories to the press. Given the number of close shaves the book catalogues, it’s surprising that Hudson’s sexual orientation didn’t become widely known long before the reports of his AIDS diagnosis, in the 1980s. But then the codes of the day could be oddly accommodating: in the 1950s, for instance, sharing a meal with gay friends in public was safe so long as they all carried briefcases.

As Griffin frequently notes, one of the weirder aspects of Hudson’s filmography is how many knowing winks it contains to the straight-guy drag he was performing. Although the delightful Doris Day vehicles he starred in sometimes send up his macho charms—getting a woman inspector to investigate his wrongdoing, Day’s character gripes in Pillow Talk, is “like sending a marshmallow to put out a bonfire”—they just as often require him to seem sexually ambiguous, until the leading lady, first reassured but soon wrong-footed and doubting her feminine wiles, is ready to fall into bed with him. Offscreen, too, Hudson is sometimes hard to interpret, which may have to do with the fact that the young man could, in Griffin’s words, be “almost effortlessly manipulated.” This quality appears to have held true throughout Hudson’s life—he comes across here as insecure, easily influenced, frequently taken advantage of. And while he could do a lot when working for a shrewd director, he wasn’t one of those stars distinctive enough to elevate the dross he was often reduced to appearing in.

Hudson seems fundamentally unresolved. This seeming lack of resolution—in life and onscreen—poses a problem for a biographer even as it makes him compelling on film whenever a script leaves room for any ambiguity. Griffin at one point suggests that Douglas Sirk’s willingness to work with Hudson more often than any other male actor made sense because Hudson “is not only the star of a Douglas Sirk melodrama, he is one.” In the figure of “Rock Hudson,” as in a Sirk masterpiece, conventionalism is turned up so high that it keeps crossing over into subversion.

Photograph © Zed Nelson from A Portrait of Hackney, published by Hoxton Mini Press

If part of Hudson’s appeal was, as Maupin hinted, that he embodied a safe, acceptable version of a forbidden pleasure, one might seek something similar in the sex robot, a figure who seems to attract ever more fevered attention. (Mere weeks ago, the Houston City Council put the kibosh on plans for the nation’s first robot brothel.) Though she—almost always she, thus far—is only taking her first imperfect steps into real-world action, she’s been given more free advance publicity than the Hollywood spin doctors could ever have dreamed of. In Turned On: Science, Sex, and Robots (Bloomsbury Sigma, $27), Kate Devlin, an expert in human-computer interaction and artificial intelligence at Goldsmiths, University of London, offers an unusually cool-headed tour of the current sexbot terrain.

Devlin’s objection to the frothings of the bot enthusiasts at one extreme and their alarmist nemeses on the other is that both lack much imagination about human sexual relations. There’s the brave-new-world evangelism of David Levy’s 2007 book Love and Sex with Robots, whose excitement at the prospect of cyborgs giving everyone what they want relies on traditional and essentialist notions about what that is—to put it crudely, the ladies yearn for reliable companionship, the gents for no-strings fucking, and hallelujah, both can soon enjoy tailor-made programming. (Levy recently pushed back his prediction of when we may actually start marrying the robots to the year 2050.) The opposite view is exemplified by the likes of Kathleen Richardson’s organization Campaign Against Sex Robots, which espouses a very similar position to that once held by antiporn feminists. Robot sex, they warn, by blurring the lines of consent and indulging men’s worst impulses, will encourage rape and other violence toward women—just as, in their view, sex work inevitably does. Devlin’s calmer, more evidence-based middle path seems appealing, especially in an area where so much polemic has already risked deadening the nerves.

Devlin is closer to Levy’s position (his assumptions about women and desire aside) than Richardson’s, and she trots around Europe and the United States meeting all the state-of-the-art bots she can with an open heart. It seems that less progress has been made than you might expect. Douglas Hines, the inventor of “Roxxxy”—whose prototype Devlin describes as “a 1980s shop store mannequin in a bad wig”—claims he was moved to create a bot that could take on anyone’s personality after losing a close friend on 9/11. Alas, Hines’s full-fledged gynoids and androids, despite his grandiose claims about sales figures, seem not to exist outside his mind. More creative and thoughtful work has resulted in the likes of Sergei Santos’s Samantha, capable of a whole range of sophisticated “interactions and responses, both vocal and physical,” and Realbotix’s Harmony, who offers intimacy and companionship via impressive lip-syncing and facial expressions, and a subtly developing personality. Still, the latter’s creator, Matt McMullen, made me laugh when he described belatedly realizing how much effort is involved in keeping a human partner happy. The bot, he tells Devlin,

needs to have a dynamic mood system that changes and fluctuates based on your interactions. Sounds great on paper—but then we started getting into it and I thought “oh my God, this is a lot of work.”

Devlin is in favor of cautious, responsible experimentation—which is, she suggests, pretty much the approach of many people who have actual hands-on involvement with current robotics. The ethical and philosophical questions raised by AI are familiar by now, but Devlin’s spin on them is often refreshing. She doesn’t necessarily accept, for instance, that the only valid or profound form of love or sexual expression must involve an exchange between two equal partners. Nor does she give much credence to the fear that large numbers of people will eventually prefer smilingly compliant machines over one another. Implicit in her approach is the notion that, if AI tends to be a heightened reflection of human fears and fantasies, there’s no reason it must remain limited to their basest forms—the imagination could in theory travel somewhere else. For instance, an artificial lover need not take the shape of a “pornified fembot” when even the humble sex toy has, as Devlin points out, already branched out into far greater formal abstraction. “Does it count as objectifying women,” she muses, “if the porn is of a human-cat hybrid? Or if someone is watching tentacle porn?” Tentacles, actually, come up more often in the book than you’d think. The wilder shores of sex tech now seem to hold out at least the possibility of exploring new models of sexual expression, ones that could suit any body or orientation and offer people some fantasy they haven’t already clamored for.

The paranoid school of anti-bot thinking seems rooted in a pessimistic view of human nature, and men in particular, as inherently selfish, angry, and violent. This view even migrates into pro-bot stances, as when sex robots are envisioned as a solution for the problems of so-called incels. Devlin is intrigued to find that incels discussing this possibility online don’t yearn to harm their hypothetical robot girlfriends: “They save that for the women.” (In fact, they may fantasize about the robots precisely as another way to punish real women, via some crude law of supply and demand: Devlin quotes one as imagining, “What happens if and when girls lose the power that they have through their vaginas and sex? It could totally alter society.”) She doubts that a robot outlet could help these guys in any meaningful way. Human violence, after all, is social and political, not just a biological impulse to be contained. This idea is present in Guy Gunaratne’s debut novel In Our Mad and Furious City (MCD x FSG Originals, $16), long-listed for the Man Booker Prize, which sets out to trace the fault lines of anger and violence in contemporary London, taking as its starting point the 2013 murder of the soldier Lee Rigby by two extremists, Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale, and the subsequent torching of several mosques. Gunaratne inhabits the minds and voices of three young men, Selvon, Yusuf, and Ardan—second-generation immigrants from the Caribbean, Pakistan, and Ireland, respectively—and two of their parents, all of them living on or near a single council estate.

At its best, the book achieves an admirable intensity and conjures a London with its own particular beauties and shifting, threatening moods, as can be seen in an early set piece involving a game of pickup soccer on the estate, which captures the rhythms of the men’s speech, their immediate sensory experience, their observations of their city and its dynamics. It also continually emphasizes the vulnerability of young men in cities who’ve so often been made objects of fear and suspicion. (There’s not a lot of light relief here, but I was struck by words and phrases I haven’t heard since hanging around with my own would-be South London toughs in my teens, who were so eager to imitate the lexicon of boys like these—“cotch,” “badman,” “bare,” “allow it.”) Gunaratne sometimes falls short of his own considerable promise—not all the voices sustain themselves, the plotting can be a little schematic, and the novel’s effects tend to weaken in places where the narrative takes on too much exposition or characters analyze their own feelings and relationships too explicitly.

All these are fairly minor quibbles for a first novel of such ambitions. But if the book suffers a more pervasive weakness, it’s at the core of its depiction of urban tension. Within a relatively short span, the reader is presented with many different instances of such tensions: the actions of the IRA and of Oswald Mosley’s thugs, street riots, smaller confrontations, and acts of rape as retribution from one family to another. Nonetheless, the book—whose author was previously a documentary filmmaker and journalist looking at similar stories from the outside—hesitates to use its access to the interior lives of its characters to impart to the reader a deeper understanding of the world it evokes. Though conflict surrounds the protagonists in both of the generations depicted, none of them ever actually commits any acts of violence—again and again, when it seems that they must, they back out, decide against, or are reprieved. It’s striking that the only scene in which we follow someone who perpetrates a deliberate violent act is also the one in which the narration, for the first and last time, slips into the third person. Cumulatively, all this raises the question of what it might be like inside the mind of a young man who is sensitive, thoughtful, anxious, afraid—as all Gunaratne’s characters are—and yet nonetheless gets caught up in fighting and causing harm, a question the novel seems perpetually poised to explore.

Mostly unspoken and yet present on every page here are some of the same vexed questions about masculinity that haunt the Hudson biography and that Devlin identifies in the widespread fear of the bots—about hardness and aggression, which is to say, about what men are expected or fantasized to be.