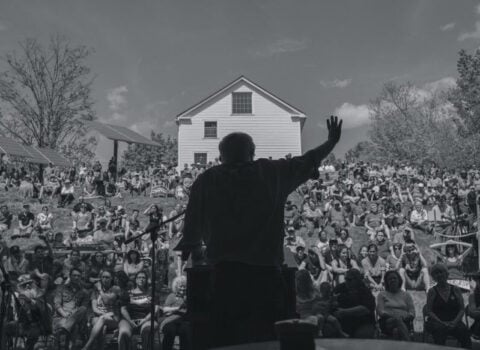

In the spring of 2018, Tequila Johnson, an African-American administrator at Tennessee State University, led a mass voter-registration drive organized by a coalition of activist groups called the Tennessee Black Voter Project. Turnout in Tennessee regularly ranks near the bottom among U.S. states, just ahead of Texas. At the time, only 65 percent of the state’s voting-age population was registered to vote, the shortfall largely among black and low-income citizens. “The African-American community has been shut out of the process, and voter suppression has really widened that gap,” Johnson told me. “I felt I had to do something.”

The drive generated ninety thousand applications. Though large numbers of the forms were promptly rejected by election officials, allegedly because they were incomplete or contained errors, turnout surged in that year’s elections, especially in the areas around Memphis and Nashville, two of the cities specifically targeted by the registration drive. Progressive candidates and causes achieved notable successes, capturing the mayor’s office in heavily populated Shelby County as well as several seats on the county commission. In Nashville, a local measure was passed introducing a police-accountability board.

Illustrations by John Ritter

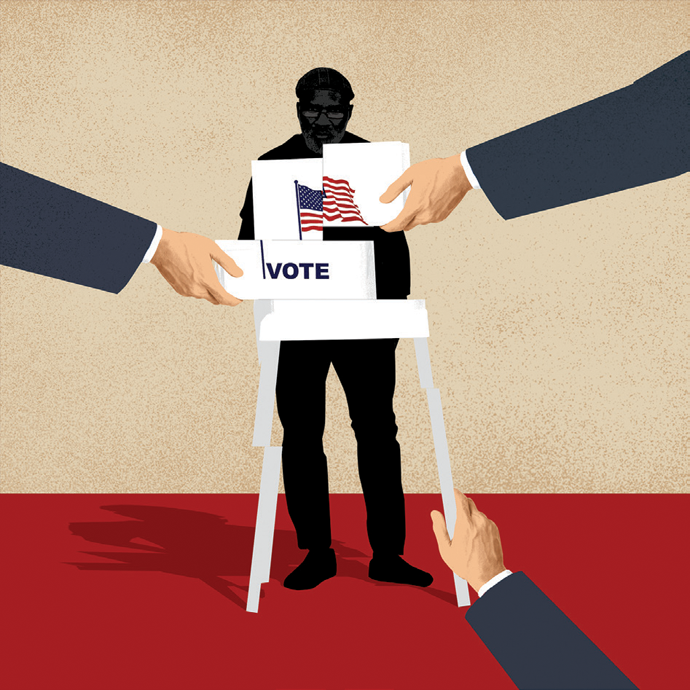

The Republican response to the Black Voter Project’s accomplishments was swift. The official charged with overseeing elections, secretary of state Tre Hargett—who, the previous year, had won a fight to retain the bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, in the state capitol—spearheaded a bill to place mass registration drives under state control and to criminalize mistakes made on applications. The bill imposed heavy fines for any group that turned in multiple incomplete applications, mandated severe penalties for failing to submit registration forms to election officials within ten days of being signed by the applicant, and required any person registering voters to receive official certification and government-administered training. (A Freedom of Information Act request filed by Johnson revealed that the proportion of incorrect forms submitted by her group was in line with previous registration drives in the state.)

Speedily passed by the Republican-controlled legislature, HB 1079 was signed by Governor Bill Lee on May 2, 2019. “We want to provide for fair, for genuine . . . for elections with integrity,” Lee declared. Civil-rights groups quickly filed suit in federal court to block the new measure. In a withering ruling against the state, a district court judge, Aleta Trauger, described the law as a “complex and punitive regulatory scheme.”

Nevertheless, it remains enormously difficult to register voters in Tennessee. “We don’t know how many people we registered are actually on the rolls,” Johnson told me, citing the applications that were summarily dismissed. As Cliff Albright, cofounder of the national group Black Voters Matter, pointed out, voter-suppression legislation serves its purpose even when struck down in court: “It intimidates people. It says, ‘Anytime you try something like this, we’re going to come after you.’ It’s not just that this particular act got squashed, it’s the message that they send.”

Outrageous as it might seem, the response of Tennessee Republicans was by no means exceptional. Across the country, the G.O.P. has maneuvered tirelessly to restrict, impede, dilute, and otherwise frustrate democratic threats to their control. To cite just a few examples: In Florida, successful litigation to prevent a ban on “pop-up” early polling stations on college campuses has been countered with a measure requiring any college hosting such sites to ensure extra parking. In Arizona, a measure passed last year restricting the use of mail-in ballots, a form of voting particularly popular among Native Americans. In Ohio, almost 200,000 voters, most of them black and poor, were purged from the rolls last year. In January 2019, Texas secretary of state David Whitley issued an Election Advisory stating that almost one hundred thousand noncitizens were registered to vote—a claim that was proved to be wholly false, and was only rescinded after Texas taxpayers spent $450,000 in its defense, settling a legal challenge from a Latino civil-rights organization.

When publicized, such cases elicit disapproving comments in the press. But whereas the violent suppression of the black vote in the 1960s turned civil rights into a dominant national issue, twenty-first-century voter suppression is all too often framed as a regrettable “anomaly,” as Albright’s fellow Black Voters Matter cofounder LaTosha Brown explained to me. Far from being anomalous, Brown insists, such behavior is “even more American than apple pie.” Indeed, voter suppression is not a matter of a few lamentable, isolated incidents; it is a carefully conceived campaign to keep political power in the hands of white Republicans, a campaign facilitated by an ideologically driven Supreme Court majority and aided by the feeble resistance offered by the Democratic Party.

The press and Democratic establishment would generally have us believe that malign foreign meddling is the greatest threat to the integrity of our elections. yes, russian trolls helped elect trump blared one New York Times headline in December 2018. A recent CNN report highlighted an ominous warning from the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security that “Russia may focus on voter suppression as a means to interfere in the 2020 presidential election.”

But Vladimir Putin played no role in George W. Bush’s election victory in 2000, the result of a dominant Republican apparatus eliminating 20,000 mostly poor, black, and Hispanic Florida voters from the rolls and guaranteeing through its Supreme Court appointees that all attempts at an accurate vote count would be struck down. (Al Gore lost the state by 537 votes.) Nor was there a foreign power behind the documented examples of voter purges in Ohio in 2004, where John Kerry lost by a narrow margin of 2.1 percent; in Wisconsin in 2016, where a voter-I.D. law appears to have played a part in dissuading up to 200,000 people, most of them minorities, from voting, in a state that Trump carried by just 23,000 votes; or in Michigan that same year, which Trump won by 10,000 votes while 70,000 presidential votes from the largely black city of Detroit mysteriously disappeared.

Undoubtedly, the most powerful enabler of U.S. voter suppression in recent years has not been foreign intervention but the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court. Its 2013 Shelby County v. Holder decision gutted the 1965 Voting Rights Act, nullifying a provision that required states and localities with a history of discrimination to get “preclearance” from the Justice Department or the D.C. district court before changing their election rules. (Chief Justice John Roberts has been venting his opposition to the Voting Rights Act since the early 1980s, when as a junior DOJ official he ghostwrote op-eds for his superiors denouncing the law.) The results of the Shelby decision were felt immediately. The Brennan Center for Justice reported that states previously covered by the 1965 act began purging voters, mostly minorities, at record rates as soon as the justices had spoken. Although the Roberts court’s (admittedly outrageous) decision in Citizens United has received far more attention and protest with regard to its effect on fair elections, Shelby’s assault on democracy has been at least as drastic and far-reaching.

Why is the systematic disenfranchisement of large numbers of citizens—what LaTosha Brown correctly calls “the dominant issue in American politics today”—so often ignored, as it has been in the ongoing Democratic presidential debates, rather than foregrounded and denounced? For an explanation, I turned to Armand Derfner, a legendary civil-rights attorney. Brought to the United States in 1940 at the age of two by Jewish parents fleeing Nazi Europe, Derfner abandoned a career with a white-shoe D.C. law firm to work on civil rights in 1960s Jim Crow Mississippi, where, for his efforts, he and his wife were shot at and his dog was poisoned. At the age of thirty, he argued (and won) his first voting-rights case before the Supreme Court; he has subsequently argued and won four more, as well as a host of landmark judgments in lower courts. After moving to Charleston, South Carolina, he suggested in a letter to the Post and Courier that

the Confederate flag should keep flying over the state Capitol. It is a useful reminder about the people inside, like a warning label on a hazardous product or a sign at the zoo saying, “Beware of the Animals.”

Currently, he is involved in a suit to invalidate a provision of Mississippi’s 1890 constitution expressly designed to prevent black former prisoners from voting, a rule that is still rigorously enforced today.

Whereas LaTosha Brown and other activists view voter suppression as all of a piece since the days of the Founding Fathers, Derfner believes that it attracts less attention now because its very nature has changed. “It used to be that the intent, at least in the South, was to stop black people voting, period,” he explained. “They didn’t want different factions of the Democratic Party competing for black voters.” Today, however, he says, “the aim is to win an election. The reason there isn’t greater awareness of the severity of the problem is because of the way it works. It’s bureaucratic, not blatant like it used to be.”

In the 1960s, a former client of Derfner’s, the civil-rights campaigner Fannie Lou Hamer, was fired, evicted, and brutally beaten by police officers as she tried to register herself and others to vote. Now, instead of clubs—and bullets—suppression tactics take the form of what Derfner calls “hindrances”—restrictive I.D. requirements, truncated voting hours, limited numbers of polling sites, and earlier registration deadlines. These individually minor impediments collectively amount to voter suppression. “If your goal is not to stop a whole bunch of people from voting, but simply to stop enough people so you can win the election,” Derfner explained, “you don’t need to stop a lot of people.”

The turn toward a more bureaucratic mode of voter suppression is not an unprecedented development. In terms of incremental impediments to black votes, Derfner told me, “What we see in the 1870s and 1880s was very like what’s going on now.” In the late nineteenth century, there were still large numbers of black voters in the South. Whites seeking to regain control after Reconstruction could not simply ban black people from voting, so they crafted hindrances. South Carolina passed the “eight box” law in 1882, requiring voters to put their ballots in the correct box for any given office—governor, lieutenant governor, state senator, and so on. Any mistake meant the vote was disallowed. While illiterate white voters were directed to the correct boxes, illiterate blacks were offered no such help. Virginia adopted the gerrymander approach, redistricting five times in ten years. “After 1890,” the Southern states “were able to get to complete disenfranchisement, and the Supreme Court upheld them every time,” Derfner explained. With the passage of the Voting Rights Act, black Americans again began voting in large numbers, and the tactics of suppression reverted to the earlier piecemeal approach. “I feel I’m watching a movie going backward,” Derfner told me, sadly.

As an example of the return of nineteenth-century tactics, Derfner cited a previously blocked Texas law, put into effect by the then attorney general, Republican Greg Abbott, within hours of the Shelby decision, that requires Texans to have a photo I.D. to register. “People say, ‘So what? Everyone has a driver’s license.’ Well, ninety-five percent of people do have licenses, but five percent don’t, and that adds up to six hundred thousand Texans.” Moreover, many Texas counties—especially those with substantial black or other minority populations—lack Department of Public Safety offices, the only places where one can obtain a driver’s license. Traveling the distance necessary to reach one often requires a car—a catch-22 for those without licenses.

This particular Texas law was eventually struck down after years of expensive trench warfare in the courts, during which time half a million Texans were prevented from voting. Texas legislators reacted to their belated setback with a modified law permitting people without photo I.D.s to vote, so long as they signed a legally binding affidavit at the polling site attesting to one of seven permissible reasons as to why they don’t have one. A number of voters are likely to be intimidated by the legalese, a fine example of a seemingly small impediment that nevertheless contributes to collective disenfranchisement.

Artfully contrived suppression strategies tend to be invisible to the casual media observer. Election Day reporting, for example, almost invariably includes accounts of long lines faced by voters in many locations themed as a welcome sign of “enthusiasm” for the democratic process. But the lines—particularly if those waiting in them are black or brown—are more often than not a sure sign of voter suppression at work. An exhaustive report by the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights revealed that 1,688 polling sites were shut down across the country between 2012 and 2018. The vast majority of these were in states such as Texas, Arizona, and Georgia, which, prior to Shelby, were obliged to clear such closures with the Justice Department. “Quite often, people don’t realize what is going on at the local level, and we needed to document that,” Vanita Gupta, the president and CEO of the Leadership Conference, told me. “The sheer scale of the closures after Shelby in states with a long history of discrimination points to a real crisis.”

Arizona’s Maricopa County, for example, which is almost one-third Latino, has lost no fewer than 171 voting sites since 2012, guaranteeing long waits and transportation difficulties. A recent nationwide study led by M. Keith Chen, an economist at U.C.L.A., demonstrated with precision that black voters must wait in line longer than white voters. Using geolocation data from 93,000 polling places across the country, researchers on the project found that voters in black neighborhoods waited 29 percent longer on average than those in white areas, and that they were also 74 percent more likely to wait for longer than half an hour.

Standing in line for extended stretches would be a deterrent for anyone, but the deterrent gets progressively stronger for those lower down the income scale. Since all attempts to make Election Day a national holiday have been resolutely beaten back—Mitch McConnell called a recent effort by Democrats a “power grab”—any hourly worker taking time off work to vote is losing money, as is someone who has to worry about the cost of childcare; the longer he or she waits, the costlier it gets. As the minutes stretch into hours, the number of poorer people who can afford to vote that day ticks lower and lower.

Republican Brian Kemp’s route to victory in the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial race was lined with closed polling sites. As secretary of state, Kemp was responsible for overseeing elections during his own campaign for governor, and he brazenly refused to resign despite the blindingly obvious conflict of interest. When local officials in Randolph County—a poor, rural community two and a half hours south of Atlanta that is 60 percent black—asked the secretary of state’s office for help in organizing the election, Kemp was happy to recommend a consultant who advised the officials to close seven of the county’s nine polling sites for being underused or for being in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. The “consolidation” of polling sites, the consultant blithely informed the community, came “highly recommended by the secretary of state” as a means of reducing election costs. (In this instance, Randolph County refused to comply with the consultant’s proposal, but 214 polling sites have been closed in Georgia since 2012, most of them in poor counties with large African-American populations.)

Kemp also took advantage of Georgia’s “use it or lose it” voting law—similar to measures in at least eight other states—by which voters are dropped from the rolls if they skip voting for a certain number of consecutive election cycles. In 2017, his office stripped half a million people of their voting rights on one day alone, arguing that if someone had failed to show up at the polls, they must have either moved away or died. Similarly fruitful was his use of an “exact match” rule stipulating that a voter application would be delayed if its information was inconsistent with the driver’s license on file. If the applicant did not provide a correction, even the most inconsequential divergence, such as a missing hyphen or capitalized letter, was treated as legitimate grounds for dismissal—a way of targeting the black and Hispanic voters (many with hyphenated names) who formed the bulk of new registrants. As it happened, the number of would-be voters Kemp’s office flagged for mistakes—53,000—almost exactly matched his 55,000-vote margin of victory.

“Voter suppression, along with gerrymandering, is a core investment strategy at the highest levels of the Republican Party,” Lauren Groh-Wargo told me recently. Formerly the campaign manager for Brian Kemp’s opponent Stacey Abrams, she is now CEO of Fair Fight Action, the group Abrams set up in the wake of the election to fight voter suppression nationwide. Among other examples of suppression tactics, Groh-Wargo mentioned a sheriff being stationed in at least one Georgia polling site on Election Day. “Ballot security” had been used by the Republican National Committee elsewhere in the country up until 1982, when a federal consent decree barred the R.N.C. from engaging in such efforts as posting armed, off-duty law-enforcement officers at the polls in minority neighborhoods and sending mailers to black neighborhoods threatening penalties for violating election laws, a practice known as “voter caging.” But in January 2018, a federal judge in New Jersey had allowed the decree to expire, arguing that the Democrats, “by a preponderance of the evidence,” had failed to demonstrate that it had ever been violated.

As an example of the subtle, bureaucratic approach to modern voter suppression highlighted by Derfner, Groh-Wargo cited provisional ballots. The 2002 Help America Vote Act gave voters the right to cast provisional ballots if their names were not on the registration list or their eligibility were somehow in doubt, the notion being that, after further review confirmed a person’s eligibility, the vote would be counted. “On the face of it, requiring someone to fill out a provisional ballot if their registration is in question is not voter suppression,” Groh-Wargo explained. “But if you look at the way provisional ballots are overused, misused, in states controlled by Republicans, it’s absolutely voter suppression.”

The predictable problems caused by “exact match” regulations and sweeping voter purges, not to mention faulty voting machines, have ensured that provisional ballots are in high demand, particularly in black precincts, but in the 2018 Georgia election, according to a lawsuit filed by Fair Fight Action, many polling sites ran out of the ballots. In other cases, officials failed to inform voters about how to use them or simply refused to supply them.

Similar examples of the misuse of this seemingly benign initiative were reported elsewhere. A study performed by the group All Voting is Local found that at Ohio’s Central State and Wilberforce universities, two historically black colleges, student voters cast a disproportionate number of provisional ballots in 2018 and were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected than were voters in the rest of the county.

Once installed as Georgia’s governor, Kemp duly resigned as secretary of state, his work well done. But his spirit lives on. His successor, Brad Raffensperger, has pledged to continue Kemp’s agenda, with a particular emphasis on combating (nonexistent) voter fraud. The state campaign-finance commission has launched probes into the actions of Abrams and her supporters, an effort that has been costly to its targets in both time and legal bills. “Make no mistake,” Groh-Wargo warned, “the Kemp election model will be the template for the Republicans nationwide in 2020.”

Naturally, those working to suppress unwelcome votes do not advertise their work as such, preferring to justify their maneuvers as a defense of voting rights. “Voter-I.D. requirements remain in place going forward to prevent fraud and ensure that election results accurately reflect the will of Texas voters,” declared Texas’s attorney general, Ken Paxton, hailing a court ruling that upheld the state’s voter-I.D. law. “Safeguarding the integrity of our elections is a primary function of state government and is essential to preserving our democratic process.”

But every so often the real agenda is laid out in plain sight. The Trump Administration’s determined efforts to add citizenship status to the 2020 census questionnaire were upended by the discovery that the move was the brainchild of the late Republican redistricting strategist Thomas Hofeller. The Supreme Court was reportedly on the verge of approving the census question, accepting the administration’s claim that it sought only to enable better enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, when Hofeller’s daughter found several hard drives detailing his plans and handed them over to the watchdog organization Common Cause. In the files, Hofeller stated outright that the census question was aimed at giving electoral advantage to “Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.” This revelation apparently made it too embarrassing for the chief justice to endorse the administration’s disingenuous argument. (One close observer of the proceedings told me he heard that Roberts changed his opinion at the last minute.)

A similarly opportune revelation last year provided insight into the thinking and personalities behind gerrymandering. In August, fourteen hundred Republican legislators, party officials, and lobbyists gathered in Austin, Texas, for the annual meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a corporate-funded nonprofit that guides state-level Republicans on legislation favorable to big business. While much of the proceedings were closed-door, at least one of these panels—titled “How to Survive Redistricting”—was recorded and a transcript was subsequently published on Slate by David Daley. “Your notes from this conference,” said moderator Cleta Mitchell, “will probably be part of a discovery demand. My advice to you is: if you don’t want it turned over in discovery, you probably ought to get rid of it before you go home.”

Gerrymandering has been a hallowed political tactic since the dawn of the republic—Patrick Henry tried to gerrymander James Madison out of winning a congressional seat—and it currently underpins Republican (and Democratic) control in many localities despite popular disfavor. A study from the Schwarzenegger Institute at the University of Southern California found that fifty-nine million Americans lived in states where Republicans had designed the districts and thereby controlled at least one chamber of the state legislature even though more people in sum had voted for Democrats in the 2018 elections.

The more enlightened Supreme Court of the 1960s did bequeath some limited constraints on gerrymandering, still irksome to its practitioners. As Hans von Spakovsky of the Heritage Foundation derisively reminded the ALEC conclave, the court “established the one person, one vote rule. That’s the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. And they created it out of whole cloth.” Von Spakovsky brought to the gathering the expertise from his days in the George W. Bush Justice Department, as a vigorous exponent of both voter-I.D. laws and the widely debunked theory of voter fraud. At the Austin conference, he lamented the constitutional provision mandating congressional apportionment based on total population as “fundamentally unfair” because “states with large numbers of aliens, particularly illegal aliens, are getting more political power.”

Along with the incendiary comments about undocumented immigrants and the unfairness of the Fourteenth Amendment, the conference speakers had plenty of concrete advice for their audience. Former Georgia representative Lynn Westmoreland—another tireless advocate for voter-I.D. laws, though he is possibly best known for his efforts to post the Ten Commandments in the House and Senate—gave detailed, practical advice on creating partisan voting districts that exclude black residents. Thomas Farr, known for defending a North Carolina voter-I.D. law deemed by an appeals court to have singled out black voters “with almost surgical precision,” expounded on techniques for defending gerrymanders against the inevitable court challenges.

Texas, a prize of supreme political importance, was a suitable venue for such a gathering. As Tory Gavito, president of the progressive donor group Way to Win, reminded me, “If you add Texas to Colorado, New Mexico, Minnesota, and Virginia, Democrats could lose Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, Georgia, and Arizona and still win the White House.” Given the electoral stakes and the fact that the white population has lagged significantly behind minorities in population growth, Texas Republicans have defended their rule with desperate intensity. It is now literally impossible to run a statewide registration drive: a worker must be a “deputized” registration agent in the county where they live, and can only register voters from that county. Other Republican approaches have been open exercises in cruelty. When the current governor, Greg Abbott, was attorney general, in 2008, he prosecuted a group of seniors for helping homebound, elderly neighbors vote by mail. By not including their own names, addresses, and signatures on the backs of the mailed ballots, they earned six months of probation and a lifelong criminal record. In 2017, Crystal Mason, an African-American mother of three, was handed a five-year prison term for violating a law that made former inmates on supervised release ineligible to vote—a law of which she was unaware. Rosa Maria Ortega, a Mexican immigrant with a green card, also voted mistakenly and is serving an eight-year sentence, after which she will be deported. When it comes to conceiving new means of hindering undesirable voters, Zenén Jaimes Pérez of the Texas Civil Rights Project told me, “They’re pretty cutting-edge down here.”

Pérez added that the state’s 2018 Senate race, in which Beto O’Rourke came within two hundred thousand votes of beating Ted Cruz, has spurred a fresh backlash of vote-suppressing creativity among the state’s Republicans. Texas Senate Bill 9 was introduced in March of last year; the House version contained a provision reallocating voting districts in a way that would have granted more polling places to majority-white districts than those populated by people of color. Among other novelties, the bill required volunteers driving people in need of assistance to the polls to fill out burdensome paperwork, and instituted penalties for the improper use of a provisional ballot.

“This was a voter-suppression bill on steroids,” Mimi Marziani told me. Marziani is president of the Texas Civil Rights Project, which led the fight against the bill, and she cited her organization’s campaign as an example of how opposition to voter suppression can attract a wide variety of activists: “We were able to call on groups advocating for people with disabilities, people who had never thought about election mechanisms and voting rights. We said, ‘This bill is going to make it harder to drive somebody with disabilities to the polls.’ ” In response, advocates for the disabled drove from all corners of the state to testify against the measure. “My child is going to be in a wheelchair for the rest of his life,” said one woman in a committee hearing. “Are you telling me he is less of a citizen?” Thanks to such powerful appeals, the bill never made it to a House vote.

There are some signs that Democrats are endeavoring to halt this repressive wave at the national level. The Democratic-controlled House has passed the For the People Act of 2019, a bill containing a number of obvious and necessary reforms, including the automatic registration of all eligible citizens. Democrats have also introduced the Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would restore and expand the original Voting Rights Act by extending its application nationwide. Unfortunately, neither has the slightest chance of passage in the Republican-led Senate. It will be left to national civil-rights groups such as the A.C.L.U., the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, and Stacey Abrams’s Fair Fight Action, along with state-level organizations such as the Tennessee Black Voter Project, to undertake the slog of registration drives, court challenges, and turnout mobilizations.

One especially potent initiative has been the fight to allow former inmates to vote. In 2018, Floridians voted by a 65 percent majority to restore voting rights to 1.4 million fellow citizens with felony convictions, though the Republican legislature was quick to respond with measures restricting the number of people thus re-enfranchised. Former Virginia governor Terry McAuliffe overcame determined Republican resistance to restore voting rights to approximately 173,000 former felons, but only managed to do so by signing off on each individual case. In Kentucky, Andy Beshear made restoring the voting rights of 140,000 citizens a central plank of his successful 2019 campaign for governor. These initiatives are still timid in comparison with Bernie Sanders’s call to allow everyone—including prisoners—to vote: “This is not a radical idea,” he has said. “If we are serious about calling ourselves a democracy, we must firmly establish that the right to vote is an inalienable and universal principle.”

Unfortunately, such clarity finds few echoes in the Democratic Party establishment, not least because election manipulation is by no means unique to Republicans. Democratic-dominated Maryland is one of the most heavily gerrymandered states in the country. (Former governor Martin O’Malley admitted in 2017 that he had intended to “create a map that, all things being legal and equal, would, nonetheless, be more likely to elect more Democrats rather than less.”) A 2010 redistricting plan in Illinois, drawn by Democratic house speaker Mike Madigan, prompted one Republican consultant to remark, “It’s kind of a work of art—in the wrong direction.” In Democratic-controlled New York State, the rules discourage challenges to incumbent officials through a requirement that primary voters must be registered members of the relevant party in advance of the election. In order to run against the Democratic establishment candidate Joe Crowley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez had to persuade thousands of voters to register as Democrats eight months before the vote. (The requirement has since been cut to two months.) She has said this was the hardest part of her entire campaign. Now, in the aftermath of her victory, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has introduced a rule aimed at preventing challengers from hiring professional campaign consultants, thus potentially further depriving voters of the possibility of choice.

Elsewhere, while the party is often generous with rhetorical support for voting rights, it’s less than forceful when it comes to actually funding efforts toward reform. LaTosha Brown noted that, while the Democrats were ultimately victorious, the mobilization of black voters in the historic 2017 Alabama Senate special election was “under-resourced” by the party. Similarly, it is usually difficult to raise money for secretary of state races in the thirty-five states where the office is elective, despite the importance of the post in terms of determining fairness in elections. “I have never heard of the national Democrats putting money into those races,” Jim Duffy, a longtime Democratic consultant, told me, “and the state parties usually have no money.” The party probably regrets having given almost no money to Karen Gievers in her failed 1998 race for Florida secretary of state. Republicans poured in $140,000 at the last minute for Katherine Harris, who would go on to make the state safe for George W. Bush’s presidential victory just two years later.

“A lot of people have been able to run under the radar for that job,” DeJuana Thompson told me. Thompson is the founder of Woke Vote, an organization that played a key role in organizing the black voters who made possible the Democratic upset in the Alabama special election. “It’s not the most glamorous position, but Georgia 2018 let everyone know there’s a lot of power in that role. We need to be giving a lot of thought about who is in the pipeline for those positions.”

Since Thompson is working to overcome obstacles erected by Republicans against Democratic candidates, one might expect the party to embrace and support her work, but that hasn’t been the case, at least not in Alabama, where, she said, “A lot of the people that we turned out have historically been disenfranchised, or at least under-engaged by the party.” As a result, many voters are uninformed or ignorant as to the rules preventing them from casting a ballot.

Given that today’s suppression often takes the form of bureaucratic traps, Thompson emphasized that defeating it requires relentless, long-term attention to detail. “In Florida, for instance, there are sixty-seven counties, and each county has its own set of election rules that you have to know,” she explained. “So that’s why it’s no use trying to organize around the time of the election, because, by then, whatever rules and tricks they’ve created for voter suppression will already be set.” “Obviously they can’t do the bubble test anymore—asking someone to count the bubbles in a bar of soap,” Thompson continued, referring to a notorious Jim Crow–era ploy to disqualify black voters. “But when someone with a college I.D. is asked for a home I.D. at the polls, when they’ve been living on campus for three years—that’s just another form of a poll tax or an unfair test. There’s a lot of different things that have been instituted that inhibit a person from being able to participate, and that’s really what the goal is.”

Armand Derfner summed up his frustration with the current state of affairs more pithily: “Why are we sending observers around to check other countries’ elections, when they should be coming here?” he asked. “These things ought to be crimes. In fact, they are crimes.”