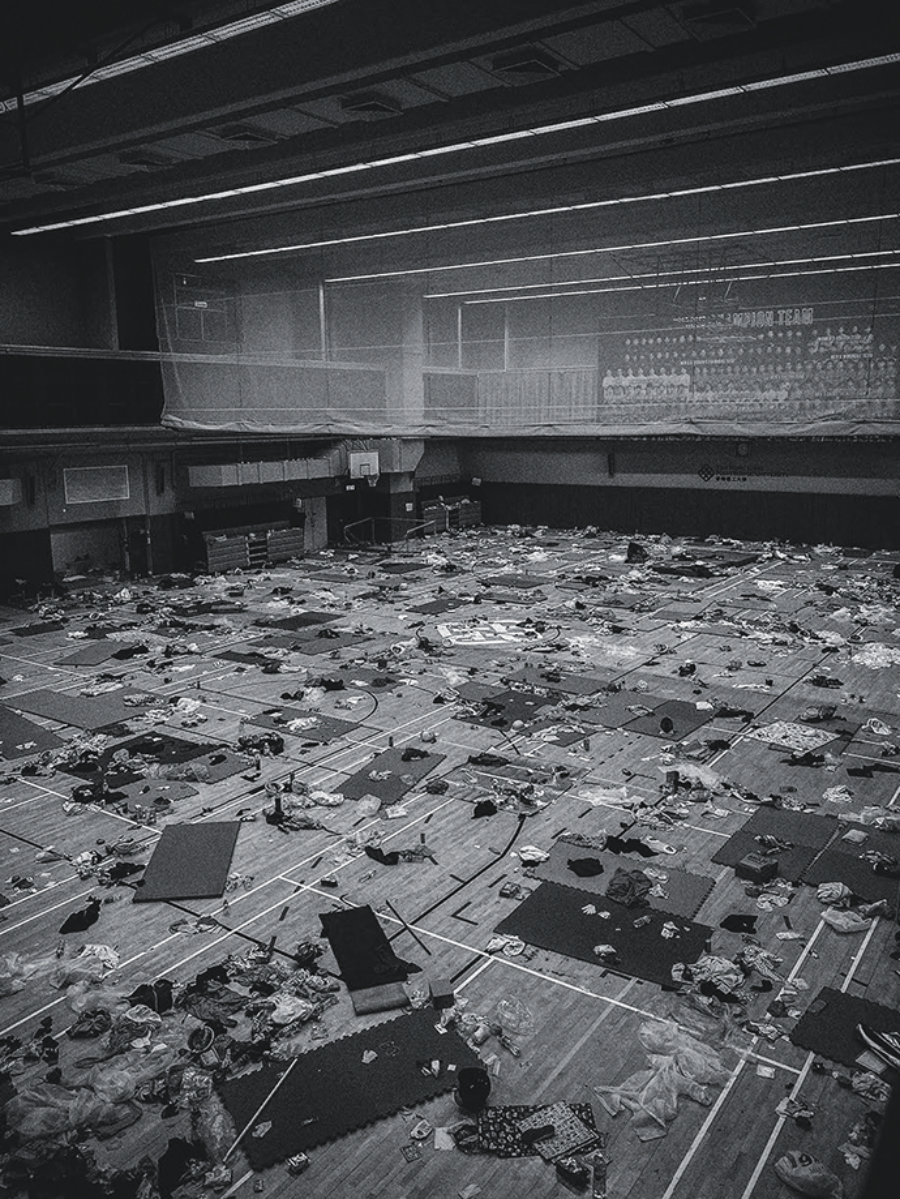

Hong Kong Polytechnic University in the aftermath of the protests, November 23, 2019 © Ashley Gilbertson/VII/Redux

When I arrived in Taiwan in January, the coronavirus was still a distant rumor, another bit of bad news from the People’s Republic of China. The Chinese mainland was on Taiwanese minds for another reason. Public attention was focused on the coming presidential and legislative elections, which pitted President Tsai Ing-wen’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) against the Kuomintang (KMT), represented by Han Kuo-yu. The two parties have very different approaches to China: the DPP strives for Taiwanese independence in all but name; the KMT, which ruled China from 1928 until it was ousted in the 1949 Communist Revolution, dreamed for a long time of ruling the mainland again, and now wants closer relations with the People’s Republic.

Sound trucks—green for the DPP and blue for the KMT—drove up and down the wide boulevards of Taipei. Posters of Tsai, a smiling, bespectacled woman, and Han, a slim, balding, rather bland-looking man, were everywhere. Massive rallies, with candidates speaking to waves of green or blue flags, were held around Peace Park, in the center of Taipei. Pop songs and party anthems could be heard from a long way off. Democracy in Taiwan is still fresh enough to provide an air of celebration.

Taiwan is an island off the southeastern coast of China with almost twenty-four million inhabitants. Unlike on the mainland, its citizens have won the dignity of electing their own government. Ancestors of Chinese people living in Taiwan today started coming over from the mainland in the thirteenth century to escape poverty, war, and oppression. The original inhabitants were members of aboriginal tribes—a minority now—and their descendants still speak a variety of Austronesian languages. Once known to Europeans as Formosa, Taiwan was a colonial backwater, ruled by the Dutch and the Spanish during the seventeenth century, then by the Manchu Qing dynasty in the eighteenth, and by the Japanese from 1895 to 1945.

Japanese colonial rule could be harsh, but it was never as brutal in Taiwan as in Korea. Taiwan was meant to be a model colony, demonstrating that Japan should be counted as an equal to Western imperial powers. Under the Japanese, Taiwan’s infrastructure—roads, power lines, hospitals—was more modern than in much of mainland China. And if most of the population chafed under Japanese colonialism, they learned to hate the regime of Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT, which ruled the island after the Japanese defeat.

On February 28, 1947, large crowds took to the streets in response to the beating of a local tobacco vendor. KMT soldiers reacted by gunning down unarmed demonstrators, and protests erupted all over the island. Mobs briefly took over government buildings, martial law was declared, and a period known as the White Terror began. Chiang’s henchmen imprisoned and murdered large numbers of Taiwanese intellectuals and professionals who resisted KMT rule. Some historians estimate that more than twenty thousand people were murdered by the government. (The term White Terror is now used loosely in Hong Kong to describe the brutality of the local police.)

Under KMT martial law, power was justified, as it always is in Chinese politics, by an official ideology that was both political and cultural. The government of the Republic of China (ROC)—still Taiwan’s official name—presumed to constitute, in exile, the legitimate government of China. Children in Taiwan were indoctrinated with KMT propaganda, which encouraged a quasi-imperial personality cult around Chiang and his family. People were taught to feel Chinese, not Taiwanese. Speaking of the 2/28 Incident and the White Terror was taboo. Any aspirations to Taiwanese independence were severely punished. Elderly mainland politicians still attended the ROC legislature as late as the 1980s, many of them in wheelchairs, as official representatives of the different regions of mainland China.

The prime symbol of this ideological fantasy was the National Palace Museum in Taipei. It was in fact much more than a museum. Housed there was a superb imperial collection of Chinese art, smuggled to Taiwan during the civil war—a symbol of political legitimacy. The ROC was the official guardian of Chinese civilization. Even as the Maoists on the mainland were smashing priceless works of art and architecture, which they regarded as noxious remnants of feudalism, in Taiwan Confucian values and high culture were considered a precious inheritance from China’s ancient past, kept safe on the island until the day when the KMT would once again rule the whole of China.

For four decades, collective identities on Taiwan were effectively split between the mainland Chinese, who arrived in the late 1940s, and those who considered themselves Taiwanese, whose nostalgia for Japanese rule grew with the loathing of mainlander oppression. What political opposition there was came from so-called outside-party (that is, outside the KMT) activists, Taiwanese who had no desire to be united with mainland China.

The peaceful transition to a democratic state took place in the 1990s. Martial law was lifted in 1987 by Chiang Ching-kuo, Chiang Kai-shek’s son, and the first free presidential election was held in 1996. The winner, Lee Teng-hui, a reformist KMT politician, was a Taiwanese who was said to have been more comfortable speaking Japanese than Mandarin.

How much has changed in Taiwan can be seen at a glance in Peace Park. In one corner stands the National Museum (not to be confused with the National Palace Museum), built in 1908 by the Japanese in a grandiose, European classicist style. On the top floor is a fine collection of natural historical objects, as well as Taiwanese tribal artifacts. The Japanese scholars who donated these items in the colonial period are praised fulsomely on explanatory placards, something that would be unthinkable in South Korea and a sign of how much the old KMT ideology has already faded.

On the other side of Peace Park is the 2/28 Memorial Museum, established in 1996. Here, in a building that once housed a colonial radio station, repressed Taiwanese history gets a thorough airing: evidence of the 1947 massacre, the names and photographs of prominent Taiwanese dissidents as well as their clothes, glasses, and other bloodstained relics of White Terror martyrdom. It is not officially described as a monument to Taiwanese independence, for that would needlessly provoke the mainland government. Instead, the museum is dedicated to Taiwanese democracy.

Outside the main entrance is a small shrine, put up recently to remember a student who died during the protests in Hong Kong. A version of the ubiquitous slogan of those demonstrations against autocratic rule—revolution in our time!—is written in Chinese characters above a black-and-white portrait of the smiling student.

Close to the 2/28 Memorial Museum stands the Chi-nan Presbyterian Church, a redbrick neo-Gothic edifice from colonial times that has been in the news recently for harboring students who have fled the police in Hong Kong. There were banners outside demanding the city’s liberation. I saw several young people dressed in black T-shirts milling around, speaking to one another in Cantonese. A middle-aged man in jeans eyed me suspiciously. After some initial hesitation, he explained in fluent Japanese that the church had a long history of human-rights activism, going back to the White Terror days. A well-known pastor there was imprisoned in the 1970s for helping Taiwanese dissidents who were sought by the police. For escaped Hong Kong activists, Chi-nan is now the first port of call.

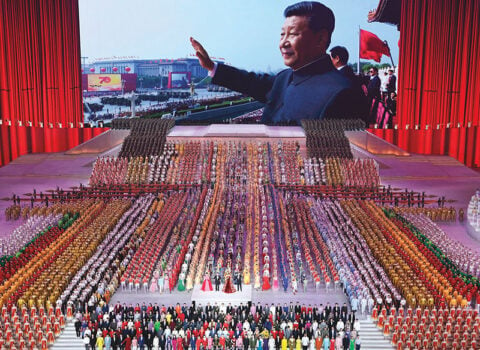

The Chinese president, Xi Jinping, sees it as his patriotic duty to return Taiwan to the motherland, by force if necessary, under the same formula as Hong Kong: “one country, two systems.” He was foolish enough to stress this goal last October. President Tsai Ing-wen, who was lagging behind Han Kuo-yu in the polls, vowed to resist the idea. Her campaign motto was a warning: “Hong Kong today, Taiwan tomorrow.” Her poll ratings shot up, and in the end, she won the election in a landslide.

A Hong Kong protest banner is held up as supporters of Tsai Ing-wen and the Democratic Progressive Party await the results of the presidential election in Taipei, Taiwan, on January 11, 2020. © Carl Court/Getty Images

Until not long ago, people in Taiwan took little notice of Hong Kong, and vice versa. This changed around 2012, when Taiwanese students protested against a wealthy local businessman named Tsai Eng-meng who was buying up major media outlets to propagate unification with the mainland. At the same time, people in Hong Kong were protesting government attempts to introduce a new school curriculum in line with Communist notions of patriotism. From then on, Taiwanese and Hong Kong activists began to communicate. Taiwanese used to shy away from the older generation of Hong Kong democrats because of their ties to the mainland, but such scruples are now obsolete. In the words of one young activist in Hong Kong: “Hong Kong students supported people in Beijing in 1989. Taiwanese are now supporting us.” Martin Lee, an eighty-one-year-old Hong Kong lawyer, who since the 1980s has campaigned tirelessly for democratic rights and the rule of law, put it more succinctly: “We can all see now that our future lies together.”

Lee is vilified in the Communist press as a traitor to the Chinese people, and he has been accused by the Chinese government of leading the protests in Hong Kong, allegedly under direction from the United States. In January, before flying to Taiwan, I met him in his office, which was decorated with a bust of Winston Churchill (a gift from America) and a model of the Goddess of Democracy that was erected in Tiananmen Square in 1989. He is one of the prominent pro-democracy figures collectively denounced in Chinese state media as the “Gang of Four”—the others being Jimmy Lai, owner of the Apple Daily newspaper; Anson Chan, a former legislator and head of Hong Kong’s civil service; and Albert Ho, a leading democratic politician who has been beaten up on several occasions by unidentified thugs with baseball bats.*

Still spry and soft-spoken, Lee told me how ironic it is that he had been denounced as a traitor, since it was he, along with Anson Chan, who had persuaded the Americans to back China’s entrance into the World Trade Organization in 2001. He had been convinced that China would learn to respect the rule of law and that respect for human rights would surely follow. At the time, Nancy Pelosi was among those arguing to keep China out of the WTO. Lee now admits that she was correct, as does Chan. There is no hint of anger in him, just the rueful manner of a man who has done everything he could and must now leave unfinished work to the younger generations.

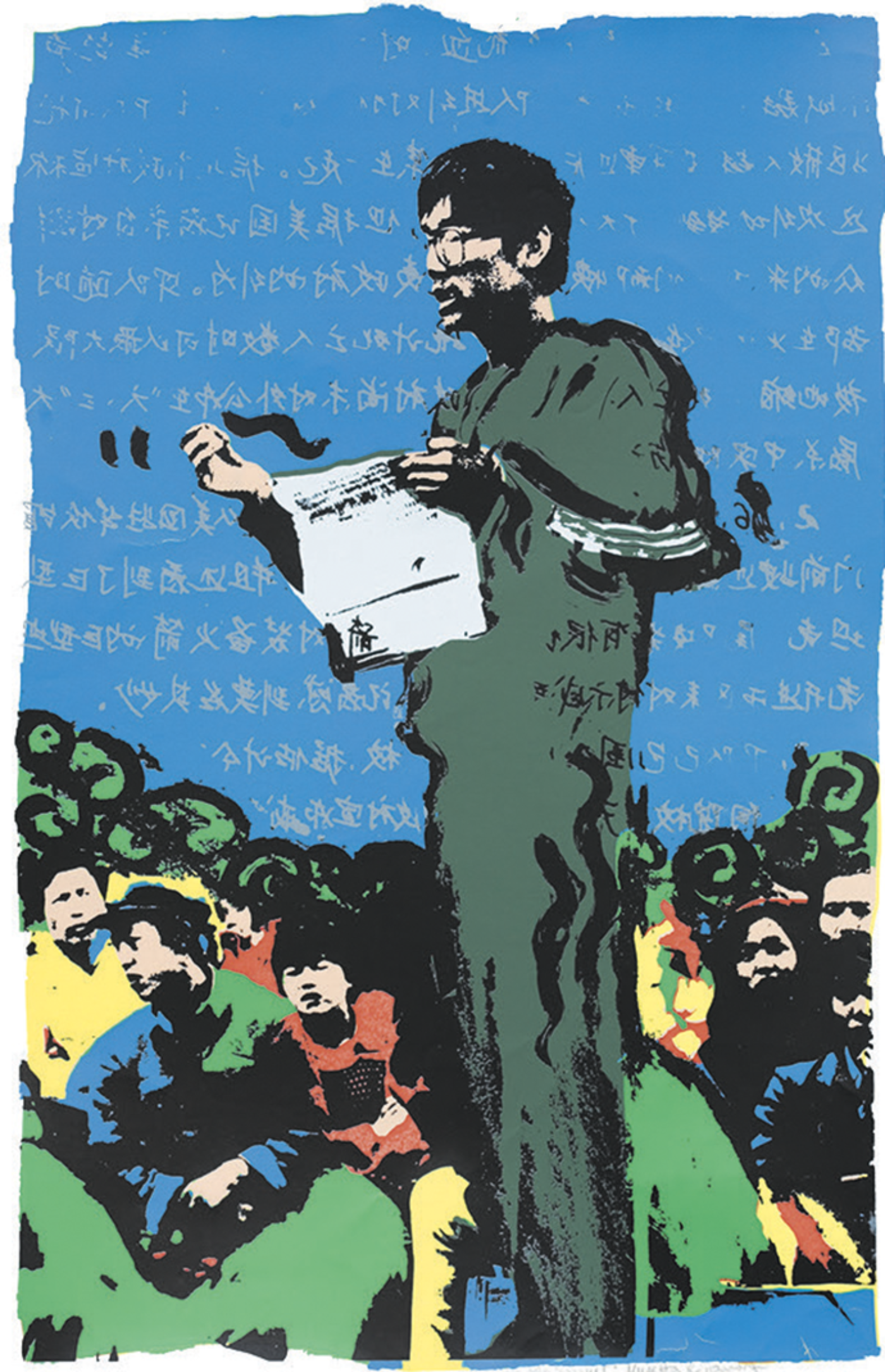

Contrary to Chinese allegations, the opposition movement in Hong Kong has no official leaders—certainly not Lee. The closest thing it has to a leader might be Joshua Wong, a university student who, in 2017, was arrested several times and held in prison for almost two months for “unlawful assembly.” He led the Umbrella Movement in 2014, when protesters occupied the Central district of Hong Kong for seventy-nine days to oppose a bill that would have allowed the Chinese government to handpick candidates for the city’s leadership. Wong has been accused by the Chinese of being a U.S. agent, among other things, and is now out on bail.

We spoke in a British-style pub, located rather incongruously in a building that also houses a mainland Chinese investment corporation. A slight man in wire-rimmed glasses with a fondness for playing video games, Wong was dressed in a black T-shirt with hong kong written in large white characters on his chest. Now twenty-three, he was born just a year before China took over the British colony. He already speaks in the efficient sound bites of a seasoned politician, while impatiently fiddling with his iPhone. He looked like a man in a hurry. More interviewers were waiting. Like many people of his generation, Wong is more radical than Martin Lee, though the two are on friendly terms. I told him about my conversation with Lee regarding China’s entry into the WTO. A rare, thin smile appeared on his lips: “Martin is a very decent British-trained barrister, but he will never be an activist.”

Although Lee happened to have been born in Hong Kong while his mother was on vacation there, his roots are on the Chinese mainland. The same is true of two other members of the Gang of Four: Anson Chan was born in Shanghai, Jimmy Lai in Guangzhou. Lee’s own father was a general in Chiang Kai-shek’s KMT army during the civil war. His parents sought refuge in the British colony in 1949, after the revolution. Many others of similar backgrounds fled to Taiwan with Chiang’s army. When I asked Lee whether he thought activists of Wong’s generation—many of whom are the grandchildren of refugees—still felt Chinese, he replied: “Over their dead bodies.” Wong himself said, after some reflection: “Ethnically Chinese, yes, but never a Chinese citizen.”

Protected by British laws, Hong Kong was for more than a century a place for refugees from China to work hard, and sometimes to become very rich, without worrying about state oppression. But it was never a democracy, let alone a separate state. Culturally, Hong Kong was a kind of Chinatown, the creative epicenter of Cantonese pop music and kung fu movies starring Chinese heroes beating big white brutes, catering to Chinatowns all over the world, from Singapore to San Francisco. Chinatown culture is a pastiche of Chinese tradition, a form of popular nostalgia for a country left behind long ago. With the rise of China, Chinatown culture lost ground to the soft power of a huge and increasingly prosperous market on the mainland. Now, some pop singers from Hong Kong and Taiwan tour Chinese cities singing in Mandarin about their love for the motherland.

A new, more political Hong Kong identity took some time to emerge. It didn’t form even after Hong Kong officially became a “special administrative region” of China in 1997. When hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers took to the streets in 1989, and every subsequent year, to protest against the murderous crackdowns in China, they did so as patriotic Chinese. My friends in Hong Kong during the Eighties and Nineties never doubted that they were Chinese.

An artist and scholar of urbanism named Sampson Wong, who was born in 1985, half a generation before Joshua Wong, told me that most people his age still supported Chinese athletes in the Beijing Olympics of 2008. We met at a Thai restaurant, known as a “yellow” establishment, meaning it was sympathetic to the democracy movement, as opposed to “blue” places that favor closer relations with China, or whose owners have been critical of the protests. (There are apps that supply such information.) I asked him when the Hong Kong identity began to replace sentimental ties to China. He said the “revolutionary moment” came in 2010, when the Chinese government made it clear that the promise of full suffrage would not be kept. But later in our conversation he recalled an earlier occasion that had impressed him: when the Olympic flame passed through Hong Kong in 2008, a young woman waved a Tibetan flag in protest. She was roundly condemned for this in the local press, but Sampson never forgot it.

“We still felt sympathetic to the idea of working with China,” he explained. “But the younger generation are anti-Chinese. They have no more illusions.” This is not just a matter of democratic politics, but has to do with culture, or indeed Chinese identity, that knotty mix of politics and tradition. Sampson explained that Hong Kong Chinese who wanted to escape from the clutches of what he calls the “Chinese Empire” used to go to Melbourne or Vancouver. Now, he says, “the only place you can go to be Chinese and out of the empire’s reach is Taiwan.”

He said this back in January, while we were on our way to a demonstration in Sheung Shui, out in the boondocks, near the Chinese border. The protest march was meant to show anger about the “invasion” of mainland Chinese—not in this case the tourists who spend vast amounts of money in luxury malls, but the poorer people who come to buy medicine to resell back in China. This might seem rather innocuous, but family shops in small market towns like Sheung Shui have been almost entirely replaced by drugstores. This has become a symbol for people who feel, in the words of one lawyer I spoke to, that “there are too many Chinese in Hong Kong.”

The march was not huge. It looped around a small shopping mall popular with mainland tourists. Young protesters in black T-shirts and black face masks faced riot police, also dressed in black, who were often the same age as the marchers. Demonstrators shouted slogans about freeing Hong Kong; an American flag was carried around as a call for U.S. attention and a deliberate insult to Chinese patriotic sensibilities; protesters held up a banner saying that people would fight till their last drop of blood.

When I lived in Hong Kong, in the 1980s, British colonial officials and Chinese tycoons liked to claim that making money was all that Hong Kong Chinese were interested in. The protesters showed how much has changed since then. There was a bracing feeling of pride in the shabby streets of Sheung Shui, and commitment, even humor. There was also some violence, most of which I witnessed at a distance. The riot police seemed more menacing than the protesters. But there were sporadic attempts to smash things, which were quickly met with baton charges, pepper spray, and random arrests.

On the way back to the city, Sampson showed me several places where more serious damage had been done, at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for example, which was under siege for two weeks, and at the Legislative Council in the center of town, which had been occupied and thoroughly trashed in July. These were the acts of a minority, often carried out after most peaceful protesters had gone home. Joshua Wong is not alone in claiming that the violence is simply a response to far worse police brutality: thousands of acts of torture and rape are alleged to have taken place in police stations and jails. “What do you think people are more afraid of?” Joshua asked me, with a hint of impatience, “Molotov cocktails or tear gas?”

Interestingly, even peaceful protesters generally excuse destructive aggression, though such behavior could so easily play into the hands of the Chinese government, which calls every protest a “riot.” Martin Lee blames the Hong Kong government for not listening to the people’s demands. Others refuse to condemn young people risking serious injury or worse on the front lines. There seemed to be a feeling of helplessness among activists of the older generation, including members of the Gang of Four. Since they had failed to deliver democracy by peaceful means, how could they criticize the young for taking more forceful measures?

Han Dongfang was a labor organizer present at Tiananmen Square in 1989. He almost died in prison near Beijing, where he was tortured and held for nearly two years without a trial. Han now runs an NGO in Hong Kong focusing on workers’ rights in China. Although he learned to speak Cantonese, he remains an outsider, a mainlander from the north. Han describes the Hong Kong identity that formed in opposition to the Chinese government as “new life emerging, like a chick from the cracked shell of an egg.” You can see it in the way people move and talk, he said. For years, Hong Kongers didn’t mind if he spoke to them in Mandarin. Now he mostly speaks in Cantonese.

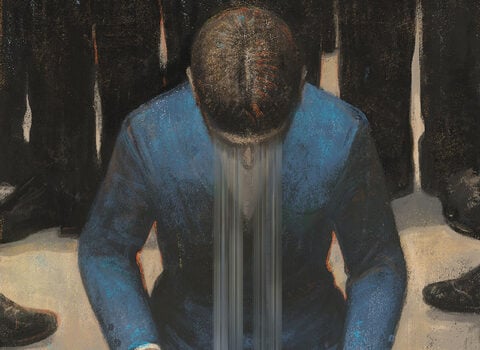

Comparing the mass protests in China in 1989 to those in Hong Kong today, Han says that the students at Tiananmen Square knew about freedom and democracy only from books: “We never actually tasted it, but people in Hong Kong had freedom, even without democracy. You take freedom for granted, until it is taken away. That is why young people are so determined.” Han, too, refuses to condemn the violence. He used to be a Gandhian, he says, but now he believes that peaceful methods won’t sway the Communist Party. “I was an idiot for projecting my experience of Tiananmen onto the situation in Hong Kong,” he told me. “The game has changed, not because of the people in Hong Kong, but because the Chinese government cheated them out of what they were promised.”

It is indeed remarkable that even after the worst acts of violence in the summer of 2019, the overwhelming winners in district council elections in November were the pro-democracy parties, who took 389 seats out of 452. The few people who have openly criticized violence as counterproductive, such as Emily Lau, a campaigner for democracy with Martin Lee since the 1980s, are dismissed as out of touch, or worse, as Chinese toadies.

After Han’s ordeal in prison, he converted to Christianity. Quite a few dissidents in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are Christians, either by birth or conversion, which adds yet another layer of complexity to the matter of Chinese identity. I have asked some of them about this over the years. They frequently link their faith to their hunger for freedom.

Martin Lee, who is Roman Catholic, put it this way: “We believe in the truth. The Communists don’t recognize the truth.” Jimmy Lai, the newspaper owner, who is one of the only Hong Kong tycoons to openly support the democracy movement, went further than that. “Our values will prevail,” he said, “because our civilization is based on the rule of law. It is strong because this is based on Christianity. We follow rules because we fear a higher power.”

Lai, who was arrested in February for taking part in an “illegal assembly” last year, is a man of great charm, with the physical bearing of a retired prizefighter and a taste for slightly garish Japanese art. His wife is a devout Catholic, and Lai converted to Christianity after the handover of Hong Kong, which he feared might lead to his arrest. “The grace of God,” he said, “allowed me to lose my fear.”

The curious thing about Lai’s rhetoric is that he identifies so much with his idea of Western civilization that he sees not just the Communist government but Chinese “values” as problems to overcome. When I argued that Chinese people, too, traditionally followed rules because of their belief in a higher power, he said: “Yes, but the higher power was the emperor, a human being.”

Despite my skepticism about Lai’s view of a civilizational clash, his point about imperial rule can’t be denied. In China, church and state have never really been separate. Chinese rulers—the Communists as much as the old emperors—have claimed legitimacy through all-encompassing ideologies, spiritual as well as political, whether Confucianism or Communism. In fact, most Chinese historical rebellions began as spiritual movements, attempts to replace one dogma with another.

Hong Kong never suffered from a conflation of religious and political goals. The city was a place to make money; higher powers were irrelevant. But young activists are struggling to preserve and expand freedoms—not just free enterprise, but free citizenship, something that people in China have never really experienced. Sampson Wong, the urbanist, told me that he was not optimistic about Hong Kong’s revolt against China. But he wouldn’t give up. “Our rebellion,” he said, without weariness or resignation, “is about our dignity.”

Many people in Hong Kong, and perhaps in the People’s Republic too—though it would be very dangerous to express it publicly—see Taiwan as a model for Chinese democracy. Life there is what political dignity looks like; it’s a living, breathing refutation of the theory that Chinese people are fated to live under dictatorships.

Later in January, I visited the headquarters of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party—a modern office building not far from the Presbyterian church. I had come to meet Lin Fei-fan, who is thirty-one, around the same age as Sampson Wong. In 2014, he led Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement, which protested against a trade agreement with China that had been adopted by the ruling KMT government without democratic debate. The protesters, worried that the deal would threaten Taiwan’s de facto independence, occupied the legislature and staged one of the largest demonstrations in Taiwan’s history: a march of half a million people through the capital. The trade agreement was never ratified. Lin is now the deputy secretary-general of the DPP.

Lin smiled when I asked him about tensions between Taiwanese and mainlanders. “That’s in the past,” he said. “People under sixty now have a strong Taiwanese identity.” He showed me a sheet of statistics: 2 percent of the population still identified as only Chinese, and 18 percent said they were both Taiwanese and Chinese. The rest identified as solely Taiwanese.

I learned from Lin that an odd reversal had taken place in Taiwanese politics. The KMT used to be the party of the elite, ruling the country with an iron hand from Taipei, while the DPP and the outside-party activists represented the more rural southern regions of the island. Han Kuo-yu, however, decided to follow the example of Donald Trump and tried to transform the KMT into a populist party, as the angry voice of the common people against the urban elites. “That’s us,” Lin said, pointing at his chest, with a look of ironic bemusement. (He holds master’s degrees from National Taiwan University and the London School of Economics.)

On the surface, then, the differences between the modern KMT and Tsai’s DPP look familiar: they are roughly the same as those between Trump’s Republicans and the Democrats. Last year, Tsai’s government was the first in Asia to legalize gay marriage. Pamphlets in the DPP office promoted the rights of women and ethnic minorities. Han, meanwhile, was trying to appeal to lower-middle-class voters who resented such policies. During the campaign, he railed against pension reforms that hit civil servants, who have traditionally been recruited from mainlander families. The KMT no longer has any designs on mainland China. The party is in favor of tightening relations with China because it is thought to be good for business, and especially good for those who benefit from Chinese tourism—shopkeepers, small traders, and tour guides. But the DPP would never accept “one country, two systems.” Lin told me that people of his generation don’t even talk about “the mainland” any longer; they say “China” now, as though it were a foreign place.

The demographic differences between the KMT and the DPP were immediately obvious in observing the two massive rallies organized on consecutive nights in Taipei before the election on January 11. The DPP crowd, waving their green flags, were relatively young and smartly turned out. The more raucous KMT supporters, waving the flags of the Republic of China, were older, and less fashionable in their appearance. DPP speeches stressed the importance of standing up for democracy and supporting Hong Kong. Speakers for the KMT talked about traditional values, family, and the alleged elitist disdain for the common people. But underlying the rhetoric of class distinctions, the main gap between the two parties still concerned China: one wanted ever-closer relations, the other did not. A man waving an American flag at the DPP rally got a huge cheer. The Taiwanese generally don’t trust Donald Trump, but he was seen as an enemy of China, and that was quite enough.

My oldest friend in Taiwan is Chiang Chun-nan, better known to foreigners as Antonio Chiang. Once an intrepid and extremely well-informed journalist, he was the person whom visiting reporters would always consult. Chiang still writes a column for Jimmy Lai’s Apple Daily newspaper. But after Taiwan’s transition to democracy, he became more than a journalist; first, a high official on the National Security Council, and now, an adviser to President Tsai on cultural affairs. He is, he said with a grin that was more like a wink, a “respectable man” now.

Speaking through the sulfurous steam of a communal hot-spring bath in the mountains overlooking Taipei, Chiang explained how he ended up in the government. “In the good old days,” he said, “we were just fighting for democracy and freedom. We didn’t talk about China, just democracy. But we were naïve. When we had our first free elections, China launched missiles across the Taiwan Strait as a warning. Democracy can’t just defend itself. That’s why I joined the National Security Council.”

Chiang was born seventy-five years ago in the south of Taiwan, the heartland of the Taiwanese identity, where more people speak a southern Chinese dialect than speak Mandarin. He was a natural supporter of the outside party. His disdain for the old mainlanders’ party goes back many decades. “The KMT,” he says, “never thought about how to protect Taiwan. They are outsiders. Their imagination is all about China.”

And yet, Chiang is not a nativist. He always gives off the feeling that he would have relished a bigger role than Taiwan can offer, to be a player on the great Chinese continent. He likes traveling in China, and he is steeped in its culture and history. His pen name, Ssu-ma Wenwu, refers to the great Chinese historian Ssu-ma Chien, who lived a hundred years before Christ. But he is aware of how wide the gap across the strait has become. Like the Gang of Four in Hong Kong, Chiang talks about how he once had “hopes of eventually joining a more open China.” “But now,” he says, “we are disillusioned. Under Xi Jinping, China wants to go its own way and impose it on us and on Hong Kong.”

On January 12, the day after the DPP won both the presidential and legislative elections with large majorities, the reaction of the Chinese Communist press was predictable. The official Xinhua News Agency blamed the DPP’s victory on “foreign intervention”: Taiwan’s “chaotic,” “Western-style democratic election” was part of an American plot to “control China.”

The sight of U.S. flags at rallies and demonstrations in Taiwan and Hong Kong might appear to confirm these dark suspicions. But it isn’t American—or Western—intervention that drives people into the streets of Hong Kong or fuels Taiwanese resistance to mainland China. It is of course Chinese meddling that does that. The assertions of Hong Kong and Taiwanese identities are not just the result of younger generations claiming homes in the countries of their birth; they are political reactions to a regime that threatens to take away their freedoms.

On my last night in Taipei, I participated in a discussion at a bookstore about politics and culture in East Asia. The crowd was earnest and mostly very young. No one mentioned their family backgrounds. This was not about the KMT or the DPP. I said something about Chinese culture in China and Taiwan. A young man came up to me afterward and very politely reminded me that he was not Chinese, but Taiwanese.

And so he is. But there are still many ways to be Chinese. In a world where quite a few people are prepared to believe that the authoritarian “China model” works better than our messy and increasingly strained democracy, it is moving to see resistance to that model in places where Chinese languages are spoken. That resistance might fail. China could crush Hong Kong and Taiwan with force. But if all Chinese should one day enjoy the dignity of free citizenship, those two tiny specks on the map of East Asia will likely have shown the way.