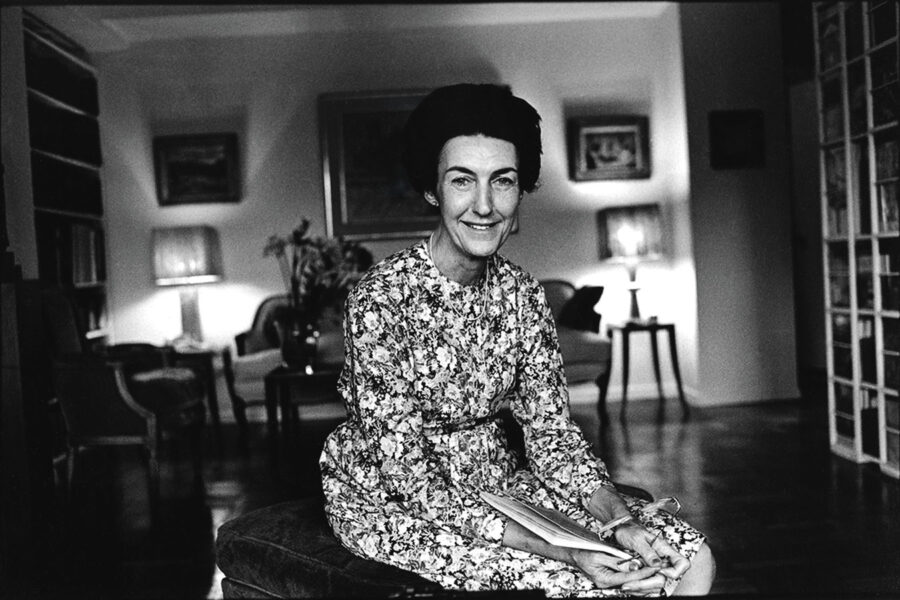

A photograph of Shirley Hazzard by Lorrie Graham © The artist. Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, Australia

Discussed in this essay:

Collected Stories, by Shirley Hazzard, edited by Brigitta Olubas. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 368 pages. $28.

Shirley Hazzard is a perfectionist’s writer. Her books, composed of dense, layered sentences, are like the sort of difficult, delicate cakes no one bothers to make anymore. They’re slender yet solid, consummate, as fascinated and affected by the mysteries of experience as they are self-assured. Striving for the “wholeness” that characterizes great art—the inherently “enigmatic quality of synthesis, which does not lend itself to analysis”—Hazzard believed literature to be “a matter of seeking accurate words to convey a human condition.” As if to balance the seriousness of her incorruptible style, the human condition she most often sought to convey was love.

If you asked me where to start with her work, like everyone else I’d probably tell you to read The Transit of Venus, her 1980 bestseller about the plaited lives of two Australian sisters and their lovers, which is widely considered a masterpiece. But I would feel I’d committed a small injustice—really, you could start anywhere. From her first stories, published in the early 1960s, to her last novel, The Great Fire, about a British war hero who travels to Japan and falls in love with an Australian teenager, which won the National Book Award in 2003, Hazzard’s fiction is remarkably consistent in theme, style, and accomplishment. Her cosmopolitan love stories are set in a globalizing, postwar midcentury against a vivid but recessed background of historical events. In each work, she seems to be rearranging her ideas like furniture, the way her characters rearrange themselves—with striking calm—within their love affairs. When Hazzard died in 2016 at the age of eighty-five, she had written two short story collections, four novels, two nonfiction books that were extremely critical of the United Nations, and a handful of other short works of nonfiction. Her two later novels, The Transit of Venus and The Great Fire, are longer and more developed than her earlier works, but most of her stories could be expanded into novels, or read as linked; any of her novels could be condensed, or chopped up, into stories. (Indeed, this is how large portions of them originally appeared, in The New Yorker.) Regardless, there is not much wrong with any of it.

She didn’t make it look easy—and it wasn’t. (According to an interview Hazzard gave with Michiko Kakutani, The Transit of Venus involved as many as twenty or thirty drafts per page.) Anyone who loves language might read a popular novel today and conclude that most professional writers don’t feel the same; the pages seem to turn themselves, and a well-chosen word, much less an unfamiliar one, is rare. Expecting readerly effort is considered elitist. To encounter Hazzard in this moment is to feel, paradoxically, relaxed: as she wrote in her manifesto-like essay “We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think,” she bestowed on “the accurate word” a huge power “in relieving the soul of incoherence.” I’ve come to think of her work as the inverse of the airy minimalism in vogue among fiction writers now. Where contemporary aphorists call on the reader to fill in the gaps of their fragmented narratives, often visually represented as white space, Hazzard manages to traverse incredible spans of time and emotion from sentence to sentence and paragraph to paragraph while fastidiously ensuring everything the reader needs to understand is there. The Transit of Venus is a novel of average length that nevertheless manages to encompass the entire lives and consciousnesses of at least four characters as well as depict changing social contexts across five decades in multiple countries. Hazzard accomplishes this not through evocative generalities or sexy suggestion, but with precision. Her writing requires the sort of sustained attention she believed art deserved, but her relationship with her reader is always reciprocal: she doesn’t create mystery but reveals its vital place in life. While she doesn’t purport to answer Why?, she understands that the magic of great fiction is in everyone, everywhere, asking.

The publication of Hazzard’s Collected Stories in an edition edited by Brigitta Olubas—comprising the two early collections that made Hazzard’s name, Cliffs of Fall (1963) and People in Glass Houses (1967), plus some uncollected material—signals a new phase in the ongoing reconsideration of her work. Recent appraisals of Hazzard read less like criticism than awe: In a short Bookforum piece published last year, Alice Gregory wrote that The Transit of Venus “moved me to a degree no book ever has. It was more a life event than a reading experience.” Michelle de Kretser begins On Shirley Hazzard, a book-length essay published in the United States in March, by describing how she sobbed for days when she learned of Hazzard’s death, though they had never met or corresponded.

It would be easy to chalk this up to nostalgia for a vanishing world of writers and intellectuals who cared about the same things Hazzard did: principles such as art, beauty, and truth, all contained within the doctrine of the right word. We could chuckle, good-naturedly, all day about how old-fashioned Hazzard was. The New York Review of Books called her “crypto-Victorian”; in her foreword to the Collected Stories, Zoë Heller writes that one of Hazzard’s young characters “is rather how one might expect George Eliot’s Dorothea Brooke to sound, were she to be spirited out of Victorian England and given contraception and an apartment.” In a Paris Review interview with J. D. McClatchy in 2005, Hazzard offered succinct dismissals of, among other things, “such contortions as deconstruction” (a futile, self-aggrandizing attempt to eliminate life’s essential mystery), “the assertiveness of the ‘New York Intellectual’ ” (narcissism of small differences), American fiction writers “intent to seem casual, sassy, democratic, ‘young’ ” (fair), and “the audible nightmare of the cell phone” (she has no idea). She revered her editor, William Maxwell, as an artist and lamented matter-of-factly that the era of William Shawn’s New Yorker, 1952–87, “can never come again.” To the occasional disbelief of a with-it critic, her characters are exceptionally well-read, and she often reminisced about the days when such a thing was not exceptional and young people could quote Wordsworth and Gibbon and Auden from memory, as she was known to do until her death. Her friendship with Graham Greene, which she describes in her memoir Greene on Capri, began when she overheard him reciting Browning in a café and supplied a line he couldn’t recall. Allusions and literary coincidences appear throughout her work, especially in The Great Fire.

Yet her refinement is less an indicator of conservatism than of hope in the possibilities of literature. “We live in a time when past concepts of an order larger than the self are dwindling away or have disappeared,” she wrote in 1982. “The testimony of the accurate word is perhaps the last great mystery to which we can make ourselves accessible, to which we can still subscribe.” She’s often said to have been interested in destiny, but that’s not exactly right. Her narratives are structured as inevitabilities in a way that heightens the role and significance of the writer without overstating it; events are heavily foreshadowed, and history, particularly the World Wars, is always refracting the present and future. At the same time, one of her strengths is the way she makes the random occurrences that appear throughout her work—sudden deaths, strange illnesses, the heartbreak of unplanned romance on the eve of a planned departure—truly stunning, the way they would be in life. The shocking ending of The Transit of Venus is partially revealed on the first page of the novel; the equally shocking reason for it only comes on the very last, and is all the more destabilizing because both events occur between the lines.

In one of her earliest stories, “Harold,” she describes a group of twenty-year-old boys as “Englishly alike in grave manners and incisive speech, in an almost womanish refinement of feature and fair skin reddened but not tanned by the sun.” They’re vacationing at an Italian pension with their family, having just received, “with quiet fortitude,” good news of their performance on their Cambridge exams:

The only criticism that might have been made of them was that their background and prospects had been provided so amply as to encroach a little on the scope of the present; nothing had been left to chance—perhaps on the assumption that chance is a detrimental element.

Again and again, such controlling rationalism is revealed to be naïve; it’s only through an acknowledgment and an acceptance of reality and its contingencies that anything can become coherent, whole.

Hazzard’s fiction takes much from her life, but the temptation to read her work autobiographically never clouds the experience. “I think there is a tendency now to write jottings about one’s own psyche and call it a novel,” Hazzard told Kakutani after The Transit of Venus was published. “My book, though, is really a story—and that might have contributed to its success.”

It’s true that stories are more fun to read than therapy transcripts, but the appeal of Hazzard’s mode is more complicated than that. Born in Sydney in 1931, to a Welsh father and a Scottish mother, Hazzard grew up frustrated, attending a private girls’ school in suburban Sydney, reading obsessively, and dreaming of escaping what she saw as “the narrowness of just about every outlook, the overt rawness, and the hypocritical puritanism” in Australia. During the war, she and her classmates were sent to the countryside. There she watched Italian prisoners of war working the fields in their red uniforms, which made them easy to spot if they tried to flee.

When she was sixteen, her father took a post with the Australian trade ministry in Hong Kong, and Hazzard left school. The family traveled to Hong Kong via Kure, a port city near Hiroshima, “twenty months after the bomb was dropped.” Hazzard reproduces the mind-bending scene in The Great Fire, which begins with the protagonist, the decorated veteran and polyglot Aldred Leith, showing up in Kure to research a book on the aftermath of the war in Asia. Hazzard’s novels and stories often begin and end with arrivals and departures, creating, along with the crypto-Victorian affect, the sense that they take place out of time, on momentous trips away from the usual, to which the profoundly changed characters may never return.

The teenage Hazzard got a job in a government intelligence office alongside young veterans with whom she could trade favorite lines of poetry; her slacker foibles are chronicled in her charming 1967 essay “Canton More Far.” She often imagined traveling alone to Shanghai or Beijing, knowing it was “unthinkable”; when she eagerly volunteered to go to the mainland to stay with a family on a sort of spy mission, she gathered no intelligence but developed sympathy for the lonely wife of her target. Before long, Hazzard fell in love with an older colleague. They planned to marry, but her sister, Valerie, contracted tuberculosis. Her family, deteriorating under her father’s drinking and her mother’s mental illness, moved again, to Wellington, New Zealand, which offered a better climate for Valerie and conveniently separated Hazzard from her lover.

The ending of The Great Fire, de Kretser suggests in her book, is a form of semiautobiographical wish fulfillment. Where Aldred Leith meets a young, bookish girl, falls in love, and eventually travels half the world to reunite with her, Hazzard’s real family stayed in New Zealand for two years, and her jilted love never progressed beyond passionate letters. The family soon relocated again, to New York, where Hazzard was hired as a typist at the United Nations. She did not like it, but within a few years—after the Suez Crisis in 1956—she was posted to Naples. She had lied on her employment application and said she spoke Italian. In reality, she’d briefly studied it after she came across a translated volume of Giacomo Leopardi’s poetry while living in Wellington, and was so moved by his work that she wanted to read it in the original.

She began to write in Italy, lonely but not “completely unprepared for extraordinary places, unpredictable events.” She would return to Italy frequently for the rest of her life, and she made it the setting of several stories as well as her two early novels, The Evening of the Holiday (1966) and The Bay of Noon (1970). She sent the first story she wrote off to The New Yorker from her regular guesthouse in Tuscany, figuring she would start at the top and work her way down; Maxwell accepted it enthusiastically and asked her to send whatever else she had. This was lucky, as she hadn’t saved a copy.

“Such destined accidents,” as she called them, continued. Though she always distanced herself from the assertive New York intellectuals, back in Manhattan she became a fixture in the city’s cultural circles because of her work in The New Yorker and her friendship with Anne Fremantle, a journalist and scholar from a prominent family who also worked at the UN. Hazzard’s meet-cute with the towering Flaubert scholar Francis Steegmuller is well known—Muriel Spark set them up at a party she threw at the Beaux Arts Hotel in 1963—and they were married within a year. Their life seems to have been the stuff of bourgeois intellectual fantasy: writing, culture, dinner parties, traveling and living abroad.

This happy, supportive relationship granted her the freedom to work on her writing, but she “preserved a precious sorrow in her work,” as Lacy Crawford put it in a 2010 profile in Narrative magazine. Hazzard’s story “In One’s Own House” describes the imminent collapse of a marriage between a patient woman and a depressed man who is about to leave the country; each character—the husband, the wife, the husband’s brother, and the husband’s mother—confidently believes the others to be ignorant of the various affections (or lack thereof) within the group, and all of them are wrong. In “A Place in the Country,” the young woman who resembles Dorothea Brooke asks her secret lover, a much older man who is married to her cousin, what she has done wrong; he replies, joking but serious, that she was born twenty years too late:

So immense and so complex did the gulf between them appear to her that it was a shock to have it simply stated as a matter of bad timing on her part. She had once been told that the earth, had it been slightly deflected on its axis, would have had no winter; and the possibility of a life shared with Clem appeared to her on the same scale of enormity and remote conjecture. Inexperienced, as he had pointed out, she had no means of knowing if his remarks were excessively unfeeling.

Her characters’ ability to parse their pain in the very moment they suffer it reflects an expatriate’s balance of experience and remove, and travel metaphors structure stories of heartbreak and yearning even when no actual trip is on the schedule. In “The Party,” a woman watches a happy married couple flirt as her own doomed relationship is ending:

Minna took up her glass again and turned it in her hand, and went on watching them . . . with something like homesickness, as if she were looking at colored slides of a country in which she had once been happy.

For Hazzard, history and memory accrete, and travel, rather than erasing the past, exposes it. On an extended trip to Naples, the English protagonist of The Evening of the Holiday recognizes “the intricate, lasting nature of any form of love” when she finds herself thinking not of Tancredi, her local flame, from whom she knows she’ll eventually have to part, but a man she had known as a schoolgirl. Similarly, the narrator of The Bay of Noon travels to Naples on a work assignment, but also as an attempt to escape her incestuous love for her brother. Reflecting on her time there from some point in the distant future, she is firm that her youthful fantasy of “arriving in a strange country, purged of the past, starting afresh” was a “delusion.” The constant resurfacing of the past may be another development of the modern world—or such a revisionist interpretation may result from the way love distorts the present and becomes “a concentration of all one’s energies.” “History and literature and song were full of enforced separations, dramatic farewells,” Tancredi thinks in The Evening of the Holiday.

But nowadays—was it because one travelled more easily, or because one acted with less finality?—people did not part. On the contrary, contemporary tragedy seemed to be bound up with their staying together. . . . In all the world, so it seemed to Tancredi, only he and she were compelled to part.

“Hazzard reserves solidarity for the vulnerable—for whoever is oppressed, disregarded, or outcast—rather than for a specific cause,” de Kretser writes. In most of Hazzard’s work, the political nature of this approach is latent—the vulnerable lover is featured while the poor and oppressed make painful, if brief, appearances. But Hazzard’s interest in individuals doesn’t preclude her from considering how systems limit their freedoms, as her contempt for the manifold failures of the United Nations shows. If her belief in the importance of possibility is one link between her interests in love and travel, her intense disgust at the organization makes more sense than those who might like to cast her as a romance novelist would allow. She believed the UN manipulated humanistic values to support a system of global capital at the expense of developing “human systems as global as our emergencies.”

In the process, she argues, the organization sapped the life of its employees, or else tricked them into serving its fruitless aims, robbing the world of any real contributions they might have made. To Hazzard, this is a tragedy. The second section of the Collected Stories, People in Glass Houses, consists of some of the best workplace literature written in English. The stories center on “the Organization,” an undisguised stand-in for the UN, but despite their weighty setting Hazzard maintains her typical emphasis on the fragility of human emotion and the vicissitudes of fate: these stories are simply more depressing than the others.

Some critics call the UN stories satirical; they display her sense for comedic timing that elsewhere functions more subtly, often in piquant dialogue or ironic asides. In Hazzard’s view, satire “is, or was, also, an exercise in accurate language, and I liked that.” Indeed, the hinge between satire and consequence in People in Glass Houses is formed by Hazzard’s reflections on the Organization’s “demoralizing” bureaucratic mode of communication; just as precise language offers a sense of “immediacy” that can make the reader feel whole, the empty platitudes, office jargon, and stacks of pointless documents that abound in the Organization are used to block anything from being said, or getting done. Algie, the lively, aging Organization translator in “Nothing in Excess,” collects contradictions in terms like “military intelligence,” “competent authorities,” “soul of efficiency,” and “easy virtue”; he is not long for his job. As Hazzard writes in her essay “The United Nations: Where Governments Go to Church”:

Why governments should twice in our century have constructed an elaborate and costly “international” enterprise for the apparent purpose of incapacitation and perverting it . . . becomes clearer with the accelerating globalism against which it is paradoxically set.

In her stories, the quotidian results of this endeavor are laid bare, though the reader gets glimpses into the larger geopolitical consequences as well. In “The Flowers of Sorrow,” the Organization’s director-general gives a speech that makes his audience uncomfortable by veering off the prepared remarks: “In my country,” the director-general says in the story, “we have a song that asks, ‘Will the flowers of joy ever equal the flowers of sorrow?’ ” For most of the Organization’s beleaguered bureaucrats, this does not compute. Even worse, the gossiping employees note later, is that the director-general concludes the answer is likely no.

But we should remember that sorrow does produce flowers of its own. It is a misunderstanding always to look for joy. One’s aim, rather, should be to conduct oneself so that one need never compromise one’s secret integrity; so that even our sufferings may enrich us—enrich us, perhaps, most of all.

The speech recalls a gibe from “Where Governments Go to Church,” which begins, “In that rarest of official documents, a moving statement . . . ” The rank-and-file’s bemused reaction to the director-general’s earnest, literary address establishes the alienating discord built into the Organization. In “The Meeting,” a man named Flinders, a conservationist recruited to serve as an “expert” on a “Project for the Reforestation of the Temperate Zone,” feels discouraged after giving a presentation on his work in a North African village; it’s clear he’s doomed when he makes reference to Euripides. Hazzard writes,

He should have been able to address the meeting in its own language—that language of ends and trends, of agenda and addenda, of concrete measures in fluid situations, which he had never set himself to master.

The experience of working there is, she suggests, literally de-moralizing: in attendance at the meeting are “a thin gentleman with a tremor from the Section on Forceful Implementation of Peace Treaties, and a young woman in a sari from Peaceful Uses of Atomic Weapons.”

People like Flinders aren’t encouraged at the Organization; they’re promised promotions that never materialize, or forced into early retirement on a whim. Swoboda, a recurring character, has been a steadfast clerk at the Organization for years and has been told repeatedly by superiors that he was in line for reward. At first, he’s described as “a man of what used to be known as average and is now known as above-average intelligence,” but the dig is followed by compassion:

The years during which he might have been formally educated had been spent by him in a camp for displaced persons, but he had educated himself by observation and reflection, and had exploited to the full a natural comprehension in human affairs.

Unfortunately, his belief that he is above the Organization means he is trapped in a cycle of anxiety and rejection; his superiors dislike his lack of self-effacement, but he’s too “over-adjusted to his problem” to quit. Whenever he has had enough, he is promised another promotion—only to have it denied again, at which point the cycle repeats. He can’t help but pity the manager who dangles the opportunity in front of him, as if a “mature and feeling person” like Swoboda would really care.

For Hazzard—who, unlike Swoboda, wasn’t supporting a family—lack of advancement at the UN was another destined accident; she told interviewers that if she’d been given any encouragement there at all, she probably wouldn’t have felt the need to start writing. That her life turned out as it did, she believed, was lucky. “We do not know why art should exist or why a few human beings should be capable of producing it and even fewer of doing so with enduring excellence,” she writes in “We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think.” Like love, great art always seems to contain some portion of inexplicability, but the argument Hazzard developed throughout her career was, in fact, empoweringly rational: it’s only in the telling that chance becomes fate. “In the telling, it is obvious,” the narrator of The Bay of Noon says. “In the telling, all things are.”