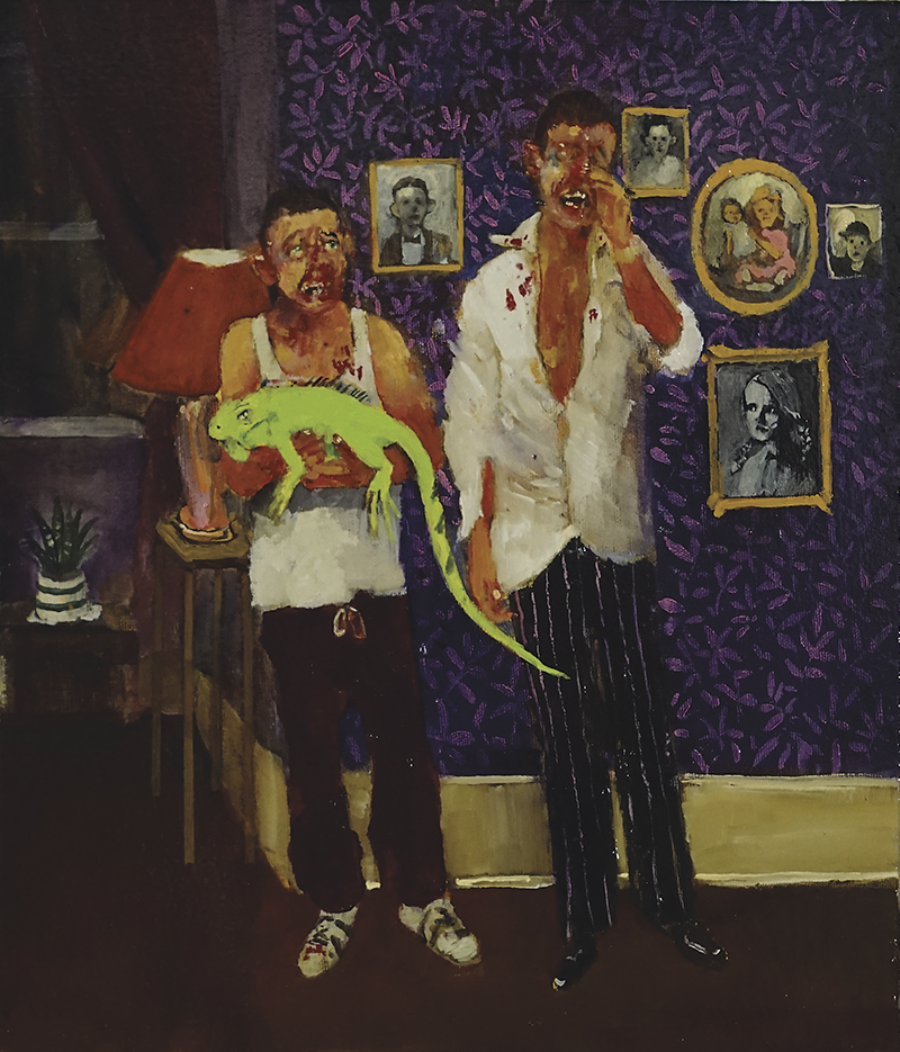

An original oil painting inspired by the story, by Michael Harrington for Harper’s Magazine © The artist

New Poets

The Dogman snuck back from the bar with two Kölsches and stuck one in front of me. An old gesture. Old for us, old for history.

“I quit drinking,” I said to him.

“You did? I keep forgetting.”

I was in a dark mood. The Dogman had been forgetting all week long, ordering two drinks and planting one before me, expressing mock astonishment at my refusal of it before downing both himself as though it were an imposition. He thought it was funny. The Dogman had a mean sense of humor. This was two months after an Amtrak train derailed in Port Richmond and killed eight people, and the Dogman was still making jokes about seeing the ghosts of dead commuters.

“I guess I’ll drink it for you.” He extradited my Kölsch to his side of the table. “Don’t worry about paying me. I make good money.”

He said this every time. Every single time.

The Dogman was an accountant in the Philadelphia office of one of the country’s largest banks. It was, by any measure, a boring job, with a modest salary, but the Dogman presented himself like a Wall Street bond trader from 1987, a figure of surplus and insouciance. Maybe he was, but only compared with me. I’d just taken a job as a delivery driver for a catering company and was therefore a man to be pitied. My life was not as I’d imagined it.

“You know, Monk,” said the Dogman. “I heard that alcoholism isn’t even a real thing. Like, you can only even get it if it runs in your family.”

“That isn’t true,” I said patiently. “And it does run in my family.”

“Oh. Well.” When outmaneuvered, the Dogman retreated to his fallback position, which was grinning like an idiot. “What does it matter if you’re a drunk, though, with your job?”

“I have to drive a van, for one.”

The Dogman grinned wider. “Didn’t stop that Amtrak engineer.”

Marc Dogana wasn’t an idiot, per se. Some people possess an emotional intelligence, and that was perhaps the sort of intelligence that the Dogman lacked. He also lacked common sense. He wasn’t terribly book smart, either. He had a business major’s disdain for objective truth. He offered a lot of opinions that sounded as though he had spent some time on their crafting, but which revealed themselves to be pretty asinine if you thought about them for more than a second. I’ll say it like this: Some people might call the Dogman an idiot. Not me, though. Me and the Dogman were friends.

And by friends, I don’t mean that we liked each other. I mean that we had, for a period of our lives, spent a lot of time drinking together and had never formally become enemies. It would have required too much effort to be his enemy. I was staying in his apartment for the time being and mostly tried to be polite.

“If you’re not drinking, that means I’m drinking by myself,” said the Dogman. “Which is a warning sign of alcoholism. So, think about the danger you’re putting me in.”

It was because of the drinking that my memories of college were hazy. The hows and whys of any one friendship eluded me. I believe I met the Dogman when a girl at a basement party threw a cup of vodka into both our sets of eyes. I never received an explanation, but if I had to guess I’d say she was aiming for the eyes of the Dogman alone, and that I was simply collateral damage, condemned by the section of floor on which fate had led me to stand. Our eyeballs burned, and it was with that burning that my friendship with the Dogman was cauterized. “We should sue the shit out of her,” he’d advised, perhaps as an activity to further bond us. “I know all about that yak. Her family is finished in Montgomery County.” These were the sort of things that the Dogman said.

“Why are we here?” I asked, watching the Dogman sip his Kölsches, one then the other so that their levels remained equal, while he peered around the room as though expecting a visitor. The Dogman had asked me to meet him in the Victory, a cavernous corporate sports bar that looked not unlike a pavilion at a Renaissance fair. We were seated at a standard four-top, but the massive refectory tables that ran the length of the hall could have accommodated fifty people each. There were not nearly that number present. There were barely any people at all. The Victory was housed within a larger complex of bars. A mall of bars. The complex was named for the local internet provider and sat on the infinite plain of parking lots in deep South Philadelphia that ring the city’s sports stadiums. Only malefactors would drink in such a bar on a Tuesday night if they weren’t waiting for a game to start. We weren’t waiting for a game to start.

“It’s a surprise,” said the Dogman. “A surprise guest.”

I didn’t care for the sound of that. There was no living person whose arrival would please me. If I knew them, I didn’t want to see them. Reunions had lost their novelty. I had already reached my point of saturation with the Dogman.

I wondered whether the bar served coffee. The decor—the tables, the Eagles banners, the bouquets of beer taps springing from every surface—suggested that the consumption of anything without booze in it was categorically discouraged.

“Okay, I’ll tell you, because I’m a little nervous,” said the Dogman. “We’re meeting Sudimack. Steve Sudimack, from school. You goddamn lungfish.”

I did not want to see Steve Sudimack. “Huh.”

“Are you excited? He called me out of the blue. He’s moving back to Philadelphia.”

“Is he still unstable?”

“More unstable,” said the Dogman. “Way less stable than before. That’s why we’re meeting him down here. I don’t want him to know where I live.”

“Why did you agree to meet him at all? Why did you answer the phone?”

The Dogman sat with his mouth ajar, as though the idea of refusing a call was anathema to his truest being. “Because it’s Sudimack. From school.” He grinned. “You gotta be there for your friends, Monk.”

Steve Sudimack, the Dogman reminded me, had dropped out of college senior year when the girl with whom he had been sleeping informed him that she was pregnant. The girl, Sonia, had herself dropped out the year before but was still loitering in North Philadelphia, going to parties and trying to “latch onto some dickhead like a remora” (to use the Dogman’s phrase). Sudimack was that dickhead. He packed up Sonia and their collective possessions in his busted Mercury sedan and drove them to his parents’ house in Scranton. The Dogman had a clear memory of the event because Sudimack had called him from a gas station outside Allentown to keen over the loss of his future. “I just laughed at him,” remembered the Dogman. “I told him to wrap it up. Get it?” The kid, Jayden, was born that fall. For the past four years, Sudimack and Sonia had lived in a cramped basement apartment, him doing contract work with his father and her cashiering part-time at Gerrity’s, raising their child in an environment that was surely characterized primarily by angst and hostility, beneath the mocking slate skies of Lackawanna County.

Then, one Saturday in early July, when the sun was hot and the cocktails were strong, Sonia got hammered and revealed that young Jayden was not actually Sudimack’s son. Sonia had been sleeping with another man at the time, and that man, when faced with the prospect of fatherhood, had mustered the cruel pragmatism necessary to tell Sonia to fuck off. She had gone to Sudimack next. And had Sudimack reacted in the same fashion, there was a third man Sonia could have gone to, and even a fourth. Sudimack, predictably, lost his shit. Tables were flipped. Cops were called. When tempers eventually cooled and blood-alcohol levels lowered, Sonia attempted to retract her admission, but Sudimack nevertheless demanded a paternity test. Three days later, when the results came back negative, Sudimack again called up the Dogman, this time to lament the needless sacrifice of four years of his youth and affirm his desire to return immediately to Philadelphia. “I just laughed again,” said the Dogman. “What an asshole.”

“When was this?” I asked.

“This was today. This was like three o’clock.”

“Wow. So this is pretty fresh for him.”

“Four years fresh,” said the Dogman, finishing his second Kölsch. “I would have gotten the test done the first day that toad tried to swindle me with her little miracle. Here, I think this is him now.”

The Dogman nodded toward the entrance, where a compact figure had just stepped in from the night. Sudimack strode through the bar like a conquering general, his short legs chopping briskly in a pair of maroon sweatpants. Sudimack wore a white tank top, like he had just come from the gym. Sudimack did not, by the look of it, give a single fuck.

My initial instinct was to go rigid and hope that Sudimack would fail to notice us, but the Dogman gave us away. “Look at this gullible Scranton-ass cuckold.”

Sudimack raised his index finger, suggesting that we wait a moment. He made a beeline for the bar.

“Getting straight to business,” the Dogman whispered, loosening his necktie. “Classic Sudimack.”

I had witnessed half a dozen of Sudimack’s altercations back in college, usually from across a room, usually with no knowledge of what had caused them, not while they were happening and not afterward. You would hear a scream or something break, look up, and there would be Sudimack locked in with another guy, one or both of them bloodied, a crowd of people shuffling backward, forming a circle, ogling the spectacle. Sudimack wasn’t particularly strong, nor was he particularly adept at landing a punch. What he had was a willingness to make use of the tools that he found in the environment: keys, ashtrays, Ping-Pong paddles, fire extinguishers. Glassware was a go-to. It did so much more damage than you’d expect. Even an inconsiderate brawler knows not to fight that way, if only because it can easily land you in prison. This near-pathological disregard for consequence was what set Sudimack apart.

“Sudimack, you remember Dennis Monk?” asked the Dogman as the guest of honor arrived at our table, a trio of whiskey tumblers clutched like an oblation in his hands.

“Not till we do this,” said Sudimack.

“I don’t drink,” I said, as one of the glasses slid in place before me.

“What?” Sudimack spat the word as though the near-empty bar was so full of music and noise that the very notion that I would even attempt to communicate with him was a source of irritation.

“Alcoholic,” said the Dogman, nodding at me.

“What is this?” demanded Sudimack. “I thought we were unwinding.” He pulled the three tumblers back toward him and started downing them.

“It’s just Monk who has the problem.” The Dogman reached for his erstwhile whiskey. “I’m still drinking.”

“Well why don’t you fucking buy a round for fucking once, you cock?” demanded Sudimack, his voice rising to a shout. He poured the contents of the last glass down his throat.

Then he flipped the four-top.

It turned out that, on his way to Philadelphia, Sudimack had stopped in Bethlehem to buy a handful of Dexedrine capsules, which were making him a bit fidgety. He now wanted some methamphetamine and was more than a little annoyed that the Dogman didn’t have any on hand. I could tell that the Dogman was genuinely offended that Sudimack would think that he, an accountant at the Philadelphia branch of one of the nation’s largest banks, would be in possession of a drug that everyone knew was for hayseeds, and yet the Dogman suffered from the tragic flaw of always wanting to please those whom he identified as greater bullies than himself. It was therefore decided that we should go acquire some meth, and that I should drive, since I was sober. It wasn’t as though we were welcome in the Victory any longer.

“You really shouldn’t have flipped that table,” I said, peering at Sudimack in the rearview mirror. It was the Dogman’s car, a leased Cadillac, and Sudimack struck a discordant image perched in its backseat with his sweatpants and Dexy jitters. I wasn’t annoyed that he had provided me with a useful excuse for never returning to the Victory, but being forced to run out of an establishment at age twenty-six was an unflattering reminder of the ever-deteriorating quality of my social circle.

“I’ve been flipping a lot of tables lately,” said Sudimack. With the stadium lights illuminating half his face, he appeared to be caught in a moment of genuine reflection.

“You know who flipped tables?” asked the Dogman, grinning. “Jesus. In the temple.”

Whatever reaction the Dogman hoped to get for that observation, we offered only silence.

“And you know who got tricked into raising somebody else’s kid?” The Dogman turned in his seat to face Sudimack. “Joseph. What a fucking idiot, right guys?”

Like a viper, Sudimack’s arm shot forward and bashed the Dogman in his nose. The latter flopped back toward the dashboard. “Fuck,” he cried. “It was a joke, you shithead.” A runnel of blood dribbled from the Dogman’s nostril.

I drove east on Pattison Avenue through the flat expanse of industrial lots, for no other reason than I had nothing else to do and nowhere else to go. I resented the Dogman for putting us in this position, on a quest for methamphetamine with an emotionally unstable coal cracker glowering at us from the backseat. It was not Sudimack’s self-destructive urges that bothered me (from my point of view, abetting his acquisition of meth was not markedly different from abetting the Dogman’s acquisition of Kölsch), but I would have preferred not to do anything that would put me on the wrong side of the law. Criminality was not sober behavior. I was wondering what the chances were of convincing Sudimack to go to a diner instead and fill his emptiness with black coffee and a corned beef special when he started tapping on his window. “This looks good. Pull over here.”

We were stopped on the old trolley tracks a few dozen yards from the Delaware Expressway overpass. Through a hole in the fence, a group of figures was partially visible in the reflected glow of a Tastykake billboard. “When I get to the fence, flash the lights a few times so they know people are waiting for me,” said Sudimack, opening his door. He slammed it with a bang and stalked off through the weeds.

“We should ditch him,” said the Dogman. He was pinching his nose shut, attempting to stanch the blood with the fabric of his necktie. He sounded like a goose.

“This is the middle of nowhere.” I flicked the headlights per Sudimack’s instructions. “You’re the one who called him your friend.”

“That was before he broke my nose,” honked the Dogman. “That bear is bad news. I wish he had taken an Amtrak down here, if you know what I mean.”

I thought back to our reunion the week prior. I had been carrying a crate of boxed lunches through a cubicle bay in an office building in Center City when I heard a familiar denigration: “Is that drunk-ass Dennis Monk?” The Dogman followed me to the street for a cigarette (he had an engraved holder, of course) and cackled with delight to hear of the many misfortunes, earned and unearned, that had stalked me since the end of college.

“Did your buddy Denhelder really die of diabetes?” he’d asked, his grin as wide as the Walt Whitman Bridge. “I heard that from Seamus, but I thought he might be fucking with me.”

“Why would he fuck with you about that?” I asked, but the Dogman waved the question off into the breeze of Market Street.

When he discovered that I was without a permanent address—I’d left Maureen in a lonely huff and was again sleeping on Ivan’s couch—the Dogman offered to sublet me the spare room in his apartment at a rate that had yet to be determined. “It’ll be just like college,” he insisted. “I’ll give you a break until I can get you a gig here, data entry or some shit, and you can stop bringing people lunch.” Caught in a pink fugue of reconciliatory goodwill, I’d accepted the proposal, already inanely picturing an engraved cigarette holder of my own, even as I knew that such holders were markers of the exact sort of people with whom I could never get along.

Now the Dogman and I were sitting in an idling Cadillac, waiting for drugs, one of us bleeding from the head. Somewhere in the night a train whistle droned like a banshee heralding our mundane doom.

Sudimack reemerged into the light of the trolley tracks, cuts checkering his face and blood spouting from his lip. He hurried back into the car. “That didn’t work,” he said, securing the door behind him. “They beat the shit out of me. Drive. Drive.”

One of the developments of my sobriety (which still felt, at eight months, quite new) was that I found myself traversing a landscape of undulating sentiment. Some days I walked the streets of Philadelphia like a pilgrim in the alleys of Jerusalem, humbled by the inimitable majesty of life, finding every joy and every sorrow experienced by any person I might meet (or see, or learn of) innately and gloriously accessible. Other days Philadelphia was just Philadelphia, and I was a miser, discerning nothing pitiable in any human being besides his ignorance of my own tribulations. Thus on one day I could be overcome with gratitude and optimism at something as meager as an offer to share an apartment with Marc Dogana, only to feel, less than a week later, apathetic as to whether he and Sudimack made it through the night with all their blood still inside their bodies. I was, day to day, recalibrating myself for a new world. The process was ongoing.

The Dogman knew a guy on Ritner Street who sold cocaine out of his row house. “How’s that sound, Sudimack?” he asked the battered malcontent in the backseat. “Would coke be alright?”

“I guess so,” came the response.

The dealer’s block was crowded and bright. Strands of Christmas lights crisscrossed the street between the houses, fat multicolored bulbs suspended like angels, offering their glow to the pedestrians who crept in twos and threes along the pavement. There seemed to be a party going on in one of the houses. A door shuddered open and shut. A yellow window fluttered with the movement of bodies. From the wrong side of the street I could hear the muffled babble of conversation, but no music. I thought the party might be our destination, but the Dogman stopped before another house across the way and banged his fist beneath the peephole.

The door opened a few inches, the chain of the lock taut across the gap. Above the chain, a face floated like a moon and frowned.

“Attilio.” The Dogman spread his arms in the pantomime of embrace. “Remember me? The Dogman? I came by with Shishkin those two times?”

It was difficult to tell from Attilio’s expression whether he remembered the Dogman or not. Perhaps the issue was that during his previous visits the Dogman had been without a streak of blood dabbed from his nose down to the end of his dangling necktie. “Why are you bloody?” asked Attilio through the gap. “Somebody fuck you up?”

“Nah, we were playing rugby.” The Dogman grinned like a mule. “Why don’t you let us in? It’s warm out here.”

Attilio considered us for a moment and then unfastened the lock. We followed him through a living room of plastic-coated furniture and artificial flowers, past a looming grandfather clock whose face told the wrong time by many hours, and down the steps to the finished basement out of which Attilio managed his business. There was a small refrigerator and a wall-mounted television and an aquarium with some sort of reptile curled in the corner. There were two parallel couches with a glass coffee table between them. Attilio ushered the three of us onto one of the couches: Sudimack, then the Dogman, then me. He sat on the other, lit a cigarette, and subjected the Dogman to a probing stare. The Dogman stared back.

“How’s Shishkin?” asked Attilio.

“I actually haven’t seen him in a while,” said the Dogman. “Have you?”

“No.”

“He’s kind of an asshole. Like, he’s . . . ” The Dogman clicked his tongue sadly. “I don’t know, he just says mean things sometimes—”

“You got meth?” asked Sudimack. Illuminated beneath the recessed white lighting of the basement, Sudimack’s face was a crime scene. He had a deep gash across one of his eyebrows, where a swollen ridge was forming above the socket. He had a sooty scrape across his cheek where it looked as though his head had been dragged against asphalt. His lip continued to bleed, and he continued to wipe at it with the collar of his tank top, which had accumulated a ghastly parody of a lipstick stain.

“What?” asked Attilio. “Do I have meth?”

“We know you don’t have meth.” The Dogman’s voice meant to be assuaging. “If we could get an eight ball, though, that’d be fantastic.” He tapped his finger to the side of his own bruised and puffy nose.

Attilio turned to me. I was free from blood and cuts and thus might have looked like the most sensible member of the group. “What do you want?” he asked me.

“I don’t want anything,” I said. “I’m sober.”

“That’s true,” said the Dogman. “Put a beer in front of him. He won’t drink it.”

“So why are you here?” asked Attilio. “Why would you come here if you’re sober?”

“Don’t worry about him,” said the Dogman. “He’s the designated driver.”

“What the fuck is this, a DUI class?” asked Sudimack. “Bro. Drugs. We have money.”

Attilio held a hand up to Sudimack, which I did not consider advisable, though it seemed to confuse Sudimack enough that he stopped speaking. Attilio looked at me. “Why are you here?”

In the metaphysical sense, I was there because the world had brought me there. My life had thus far consisted of the world bringing me to various places, sometimes for the best, more often for the worst. I had emotional responses to these places, of course, and to the other people that inhabited them, but complain as I might I mostly just kept floating along to the next thing: the next event, the next phase, the next vista. What else could I do? The most aggressive action I’d ever taken—the act by which I’d most attempted to buck the order of things—was getting sober. Though even that was not an act so much as the cessation of an act. And even sober, the ride continued, through landscapes hospitable and otherwise. When I heard people speak of their great plans, their ambitions, the way they were going to change their lives, I was always dumbfounded. What could you do, really? What could any of us really do? I couldn’t stop time, couldn’t go back, couldn’t divert the flow of the universe. No one could. If there was a key to being a person—a functional person, one who lived a long time in a relatively small amount of pain—it seemed to be doing as little as possible.

“I’m just seeing where the evening takes me,” I said.

Attilio shook his head. “I can’t help you,” he said to the Dogman. “I don’t have anything.”

“Attilio, buddy,” said the Dogman. “Come on. You know me. If you could just—”

“I don’t have anything for you. I don’t like him”—Attilio pointed to Sudimack—“and I don’t like him”—Attilio pointed to me—“and I don’t like you. Maybe you’ll come back with Shishkin and I’ll have something for you. But this is weird.” He waved his hand across our triptych. “This makes me uncomfortable.”

The Dogman frowned. I laughed.

Sudimack pointed at the aquarium. “What kind of lizard is that?”

It was the Dogman who flipped the table this time.

He had been attempting, with greater and greater adamance, to convince Attilio to sell him an eight ball, but Attilio was too busy protesting the fact that Sudimack had risen and started toward the aquarium in the corner of the room. “Yo, don’t go over there. What are you doing? What’s he doing?”

“Attilio,” said the Dogman, as though all the other words in the English language had left his vocabulary. “Attilio. Attilio.”

“Don’t go near that tank,” Attilio called. “Yo, Dogboy, you gotta get your friends the fuck out of here—”

“Attilio. Attilio. Attilio.”

“—before this busted-face freak touches my lizard.” Attilio was shouting now. “So help me God—”

When the table flipped, no one was more surprised than me. The Dogman had a temper, but it manifested verbally, never physically. When he shot to his feet, his palms lifting the edge of the glass tabletop, my expression must have been one of pure incredulity. The table hopped a foot into the air, tipped perpendicular, then met the floor with a crash and a hail of shards. Before the pane had completely shattered, Attilio leapt backward onto the seat of his couch. I looked up to see him wielding, as if from nowhere, an eighteen-inch wooden baseball bat. It was the kind they handed out at the ballpark on fan appreciation days. He must have kept it hidden in the couch cushions. I sank lower into my own seat, wondering if Attilio regarded me as an enemy combatant (and if he would be correct to regard me as such). The Dogman was on his feet and therefore posed a greater threat. Standing on the couch, Attilio had a significant height advantage, and the Dogman, who seemed to have run out of ideas after flipping the table, looked very much in danger of having his temple beaten in by a miniature bat.

Then Attilio was pelted in the face by his own lizard.

The animal flew through the air with such swiftness and precision that it took me a moment to realize that it had been hurled. The Dogman dove at the momentarily confused drug dealer’s knees, knocking him to the floor. Sudimack leapt onto the pile, and I, discerning that my participation was unneeded, ran up the basement stairs and out of the house.

The world is, at times, confounding. I stood on Ritner Street beneath an artificial sky strewn with a thousand multicolored Christmas stars, though it was the first week of July. Night is dark and sometimes we let it be dark, and sometimes we drown it in tinted light. Night is lonely and sometimes we let it be lonely, and sometimes we settle it with strangers. Half a dozen people stood across the street, smoking cigarettes before the party house. One of them was holding a steaming paper cup and I could almost smell the coffee. A woman came out of the house and stood on the stoop and said, “Come inside, everybody, we’re starting again.” She looked right at me and said, “Come inside, we’re starting the second half.” I walked across the street, under the lights, and I followed them as they filed through the doorway.

What I’d mistaken for a party was actually something more organized, with chairs placed around the living room oriented toward one corner where a space had been cleared for a speaker. About thirty people were finding their seats or filing into the spaces along the walls. I took an empty spot by a window, next to a thin table with a spread of fruit, antipasto, and a carafe of wine. The wine precluded the possibility that I had wandered into an AA meeting. Perhaps it was a prayer group. A real estate seminar. I didn’t care. I helped myself to a cup of black coffee and stood there with my nose in it, the pungent steam rising up and unleashing a wave of tranquility down my spine. An older woman reached over for a napkin, flashing me a beg your pardon smile, and I knew I was in a place of benevolent humanism.

The woman from the stoop was playing the role of host, and she stepped into the speaker’s corner with her palms clasped and her eyes gleaming. I inferred from her praises of the previous performers that I had entered some sort of storytelling event, where people got up and talked out an unwritten anecdote from their lives. I did not find that premise immediately appealing, but no one in the room was covered in blood, and that had become an increasingly endearing quality for me over the course of the previous hour. I could withstand a story or two.

“Our next performer,” said the host excitedly, “is a South Philadelphia native and a genuine treasure. We’re so lucky to still have her here among us, and so very, very grateful. Please help me in welcoming to the stage our friend Tracey Basilotta.”

There was an inordinate amount of clapping as Tracey moved to the speaker’s corner. She must have been a scene favorite. I could sense the simmer of anticipation in the modest audience, the flicker in the attentiveness of the room. She was a small woman, right on the cusp of middle age, her hair and sweater both suggesting the staticky lightness of feathers. She held an apple in one hand, gripping it like a skull, her wrist bent beneath the weight of all its inherent symbolism, and I could tell she was a woman who believed in her own purpose.

“This is a new story,” she said. “I’m still figuring out the shape of it. Part of it only happened recently. And, actually, I suppose, it’s still ongoing. Because I myself am ongoing, and life is ongoing, and we don’t yet know what the end looks like.”

Around me, people nodded. They appeared so vulnerable in their chairs, so hungry for a narrative that might supersede their own.

Tracey cleared her throat. “I was on a train that flew.”

Tracey’s story went like this: She was not a successful person. She was not an ambitious person. If she was an intelligent person, it was the kind of intelligence that had never led to any money, which was therefore no kind of intelligence at all. She’d grown up not far from where we sat, on Iseminger Street near Marconi Plaza. She’d grown up with the vague notion of leaving the city, though never with a fixed location in her mind. She ended up in Chicago. It was a school that lured her there, though once that was done she’d struggled to find a reason to stay. A vocation would have served, though she found none. A passion, then, perhaps, though an inventory of herself did not identify one. She was not a skilled person. She was not a talented person. If she was a funny person, it was the sort of funniness that appealed much more to those who understood her intimately than to those who didn’t know her. She had few of those intimate people. She stayed in Chicago anyway. She married a man, though he quickly felt less like an anchor than a millstone. She loved him, yes, but it was relative. Their love was a small love. Greater love was reserved for greater, lovelier couples. She was not a beautiful person. She was not a person whom people remembered once she walked out of a room. If she was notable in any way, it was for the way that others assumed, with very little evidence, that she was dependable. She was forever being asked by acquaintances to water plants, to look after pets. She was forever being listed as a reference for job and apartment and adoption applications. Even though her bills were paid late. Even though she left her husband after an unremarkable weekend in Bayfield, Wisconsin. She was not a dependable person. She was not an organized person. If her life conformed to any recognizable shape, it was simply because she had not found a way to break that shape. A recognizable shape was a mark of smallness. She wanted bigness. She left Chicago. She lived in Seattle. She lived in Boston. She lived in Washington, D.C. Her apartments were so similar to one another that she could not now remember which belonged to which city. She married another man. She left him, too. She took him back, two years later, out of resignation more than anything else. She was not a stubborn person. She was not a steadfast person. If she had any consistency of behavior, it was a tendency to waffle. Which was just a form of inconsistency, when it came down to it. And inconsistency was a trait upon which others could graft whatever tendencies they desired to behold. She left her second husband again. She got a tattoo. She entered a graduate program and dropped out after two semesters. She came home to Philadelphia, where an old friend gave her a stable job. She lived now, again, not far from where we sat, on Randolph Street near Whitman Plaza. And she supposed she was the sort of boring person who was always destined to end up back where she began. And she supposed she was a foolish person to have thought that any other life might lie before her. Even so, she was a person with self-awareness. And she was a person conscious of the brevity of life. And if she kept on living in a way that left her less than satisfied, it was only because there was no other way that she knew how to live. She tried to cook different foods. She tried to date different men. She tried to go different places, to see different neighborhoods in different cities whenever the opportunity arose. Just that May, she had boarded an Amtrak train at 30th Street Station. She had meant to go to New York but ended up, via circumstances that were painfully confusing, no farther from home than a gravelly field in Port Richmond.

It was only later, when the events were explained to her, that she was struck by their significance. She had, at four decades and one hundred miles per hour, come to a place where the tracks curved one way and the train went another. It slipped the rails and sailed over air, into nothingness, untethered to the predetermined course of zones and maps and schedules, unconcerned with the laws that governed physics and nature, and it flew—for who is to say that a train cannot fly? Simply because, on all the days that preceded that one, trains had been bound to the earth? But any day, any moment, is new and different from any moment that has ever come before it, because the order of occurrences has not yet solidified into unyielding history. It is still pliable and subject to influence. Subject to improvisation, to spontaneity. To whim. She inhabited a present—a present finite only if one insisted on measuring it in time—and in that present a train could do such unexpected things. It could drive across the empty air as though it were solid as any rail, as though the only thing keeping any of us from liberation is our insistence on hewing to the tracks before us.

“And I won’t talk about the way it came down,” said Tracey. “I’m not yet ready to talk about the way it came down, because it hit the earth in a way that I will never forget. But that is not the topic of this story. This is a story about flight.”

The room was silent. I could hear the hum of the refrigerator in the kitchen, the rattle of the air conditioner in the backyard.

Tracey held the apple aloft. “We know that it’s the nature of all objects to fall through space. I understand that. I accept it. But one day, in this universe of endless universes, I believe there’s going to be something that doesn’t fall. That doesn’t have to fall. I have to believe that.” She gripped her prop by its stem, and we all looked on, soundlessly, breathlessly, as she let it go. We half expected, half desired, half required with half the fibers in our bodies that the apple would float there once she released it. We watched like children, we idiots. It fell to the floor with a soft crunch as its flesh compacted under the force of its plummet.

We laughed. Laughed at ourselves. The tension broke. The spell snapped like a soap bubble.

Tracey smiled, shrugged. “So, not tonight. But one day. Thank you, everyone.”

I saw them after the applause began, when I cast an investigative glance around the room. They had snuck in during Tracey’s story and were loitering quietly along the back wall. The Dogman’s mouth was now as bloody as his nose, and his shirt was dotted with tiny stained holes where shards of the coffee table had pricked his skin. Sudimack had blood on his knuckles. In his hands he held and absentmindedly stroked Attilio’s pet lizard like a familiar spirit. The two of them were glassy-eyed from whatever substances they had found in the dealer’s basement. They swayed, smiling like lunatics, mutely at the edge of the room.

The host returned to the speaking corner and requested another round of applause for Tracey. “These are difficult times,” she said solemnly. “Death and injury seem to come sneaking up in ever more sudden and upsetting ways.” There was a gentle murmur of agreement from the room. I may have murmured along with them. “I thought,” the host continued, “that it might be alleviating in these times to go around and each speak a name of someone we’ve lost. It doesn’t have to be from violence, necessarily, since a loss is always violent. Just someone who has passed from our lives. I’ll begin.” And then she said a name, a name that meant nothing to me, a name that might have meant nothing to anyone in the house other than herself.

Tracey, who still stood near the front of the room, said her name next. I didn’t recognize that name either.

The remembrance continued through the audience, with strangers saying strange names, and I thought of what name I might say when it came to be my turn. I thought of the dead people I had known. That was the assignment, to name one of them. But, really, I had lost more than dead people. Most of the people I had ever known, most of the people I had ever cared for, had exited my life, and I would only ever know them again if I sought them out and reconciled. Friends and family and people I had loved, whose lives had diverged from mine in sharp and gradual ways. I could have said any of their names and meant them just as much as the names of my dead. I could have said my own name, and the people in that room would not have known. Except for the two who knew me.

I looked back at them, their bruised and broken faces. I hated them for knowing me. They were a check on me to remain myself and to never be any other person. How can you change if every mistake and humiliation of your life is folklore for those who witnessed it? An anecdote in the mouths of those whom fate sat on the stool next to you when you were young and brutal and gullible and scared? Dennis Monk was still those things. Why couldn’t I say that he is dead? Why couldn’t I be a new man tomorrow?

The remembrance was moving clockwise around the room, and I realized it would reach Sudimack and the Dogman before I had a chance to speak. I realized it before they did, lolling like sunflowers against the wall. I watched as the last anonymous audience members spoke their anonymous names, and then it was Sudimack’s turn. Sudimack, who fought dirty and indiscriminately. Sudimack, who looked so much like a battlefield ghost that I couldn’t believe that no one had tried to escort him from the premises.

Sudimack, whose eyes were welling with tears.

“Jayden,” he said to the assembled people. “My son. I lost my son today.”

In the house there was an intake of breath. I felt it pass my own lips. Next to Sudimack, the Dogman (who had taken possession of Attilio’s lizard and was squeezing it like a leathery doll) wailed with all the muscles in his throat. One of the men sitting nearby reached out and placed a hand on the Dogman’s shoulder. I set my fingers down on the refreshment table to steady myself.

“I had a three-year-old son,” said Sudimack, his breath fragmenting into syllable-length gasps, his knuckles clenched and raised to his temples. “And I lost him today. I lost him forever.”

“My God,” prayed the host at the front of the room.

“You poor man,” sighed Tracey, her voice as soft as feathers.

The tracks pull the train out of the station, thread it through the woolen night. Feel its compelled glide along the curves, its fixed orbit, the spine of rails and ties that dictates the arc of cars, the transit of passengers, the order of days, the epochs of a life. Could you stop it with your mind alone? With your shoulder braced against the window? Could you will the flanges to crumple, the wheels to hop the rail? I think we’ll go this way now. This way over here.

And with a swat I overturned the table, because there were new poets in town, and I knew that words alone would never satiate them.