Illustrations by Kristen Radtke

abu huzayfah: The blood was just—it was warm, and it sprayed everywhere.

[Music]

abu huzayfah: And the guy cried—was crying and screaming. He did not die after the first time. The second time or so, he probably just slouched over. That was—

rukmini callimachi: How hard is it to put a knife into somebody?

abu huzayfah: It’s hard. I had to stab him multiple times.

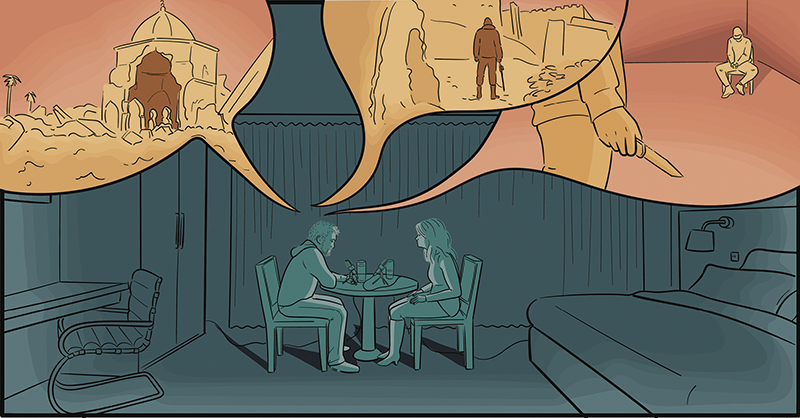

In Chapter Five of Caliphate, the now-debunked podcast from the New York Times, a young Canadian named Shehroze Chaudhry explains how he came to stab a man in the heart on behalf of the Islamic State. Back in 2014, Chaudhry, who went by the nom de guerre Abu Huzayfah, allegedly emptied his bank account and traveled to Syria to join the Islamic State, which assigned him to a police unit tasked with enforcing its strict interpretation of sharia law. Over the next six months, he told the Times, he killed two people on behalf of the group. Eventually, he became disillusioned and returned to Canada.

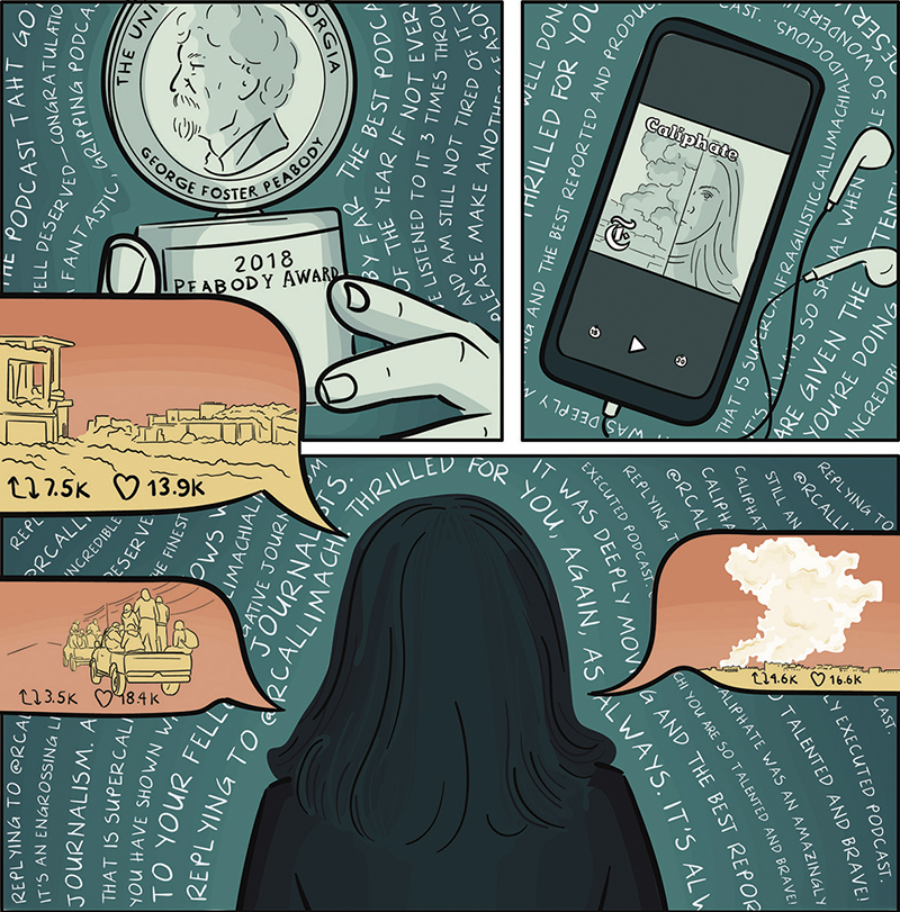

The interview was recorded in a Toronto hotel room in November 2016. Asking questions in a mellifluous staccato was Rukmini Callimachi, the paper’s resident expert on the Islamic State. When Caliphate aired in 2018, it was a roaring success, drawing millions of listeners, many of whom had never read a Times article about Syria or Islamist terrorism. The project synced perfectly with the mission of the paper’s executive editor, Dean Baquet, and its CEO, Mark Thompson: to refresh the Gray Lady for a new multimedia age. And it contained startling revelations that led to righteous indignation in the Canadian Parliament and media. How was it possible that a terrorist had been allowed to return to a normal life in Canada after committing murder?

Shortly after Chapter Four aired, however, Chaudhry gave an interview to a Canadian journalist, Nazim Baksh, in which he walked back some of his claims. He told Baksh that he’d never executed anyone. Around the same time, he was also taken in for questioning by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Chaudhry had already been on their radar, but the outcry that followed his appearance on Caliphate likely triggered the investigation.

The RCMP found no evidence that Chaudhry had traveled to Syria. In September 2020, he was charged with perpetrating a terrorist hoax. After initially defending its reporting, the Times launched an internal investigation, which confirmed in December that Chaudhry had “almost certainly never been to Syria.” The paper published a mea culpa and appended an editorial note to the podcast, acknowledging that the episodes that told Chaudhry’s story “did not meet our standards for accuracy.” The Times also returned the awards and citations it had picked up for Caliphate—including a Peabody Award, one of the highest distinctions in journalism—and permanently removed Callimachi from the terror beat.

But the investigation’s findings did not explain how the Times had been duped by a twentysomething with time on his hands. Serious red flags early in his story should have given the paper pause. Chaudhry’s claim that he had been granted a job as an Islamic State police officer was dubious: he did not speak fluent Arabic and would have had trouble communicating with the local population. As an unskilled newbie in one of the world’s most paranoid organizations, he said he had been driven to meet with the Islamic State’s secret service, which was plotting attacks in Europe. His account of fleeing Islamic State territory on a motorbike—somehow avoiding throngs of trigger-happy militants and their checkpoints—was risible, and may owe something to the wartime caper The Great Escape. A simple Google search would have revealed that the method of execution Chaudhry described—stabbing a person through the heart—was extremely rare in Islamic State–occupied Syria and Iraq. The first reports of its use were published in May 2016, two years after Chaudhry allegedly left Syria but only six months before he met the team from Caliphate. More than anything else, why in the world would a returning Islamic State terrorist own up to murder knowing that he’d very likely be prosecuted by the Canadian authorities as a result?

Callimachi was the face of the podcast, and since its unraveling, she has become a lightning rod for criticism—accused of everything from sensationalism to Islamophobia. Callimachi’s reporting record is thick with errors, and she deserves her share of blame for the project’s failure, but the real problem, according to five Times journalists I spoke with, is that senior editors ignored numerous warnings about her work long before the making of Caliphate. Three Times journalists who cover the Middle East, who all asked to speak anonymously so as not to risk their jobs, told me that they and several of their colleagues had raised concerns with senior editors about Callimachi’s methods beginning with her first stories for the paper in 2014. They were ignored or intimidated into silence.

“Senior editors doubled down on the narratives that they wanted her to produce,” one correspondent told me, “and also doubled down on their own decision to make Rukmini a star. Anything that challenged that, they wanted to disregard or discredit.” In the aftermath of Caliphate’s disgrace, this reporter continued, some of them have “owned up to it privately, but not publicly. The Times has not been transparent.” From the start, according to the Times reporters I spoke to, Callimachi was encouraged to write blockbuster stories without any of the institutional checks that should have gone with the brief. (The New York Times did not respond to a request for comment.)

February 2014, the month of Chaudhry’s purported trip to Syria, was also the month Rukmini Callimachi got poached by the New York Times. Her career was on the way up. A refugee who had fled Romania with her family at the age of five, educated at Dartmouth and Oxford, Callimachi had flirted with a career as a poet before jumping on a plane to Gujarat, India, to cover the 2001 earthquake. Her reporting was published in Time magazine. She was hired in 2003 by the Associated Press, and several years later, she was appointed its correspondent in West Africa, where she won praise for her work on the exploitation of children. In 2013, she got her hands on internal Al Qaeda documents as the group fled Timbuktu, which yielded new insights into the mundane administration of terror. That story earned Callimachi her second Pulitzer Prize nomination, and caught the eye of editors at the Times. She soon joined its team of international correspondents covering Islamic extremism in the Middle East.

For a brief period that year, Callimachi and I were on the same beat, she for the Times, I for Harper’s Magazine and Vanity Fair. We spoke on the phone in August, in the wary way that journalists do when they’re onto the same story. She was a sharp-elbowed scoop hunter in the sometimes genteel world of foreign correspondents, and I liked her immediately. Riveting Page One splashes marked her arrival at the paper. One, published on October 25, 2014, as the horror before the beheadings, described the Islamic State’s campaign of kidnapping Western aid workers and journalists. It was a difficult story to report. Most of the freed Europeans were reluctant to talk on the record because not all of the hostages had been released and because their governments and NGOs had shamefacedly paid millions of euros in ransom to the Islamic State.

One person who would talk was Marcin Suder, a Polish photojournalist who was abducted from the Syrian town of Saraqib, and so he became a main character in Callimachi’s story. But Suder was clear, in his correspondence both with me and with Callimachi, that he had no idea who had kidnapped him. And I saw no way it could have been the Islamic State. By the time Suder was abducted, the group had begun to gather all its Western hostages in a hospital in Aleppo, and none that I spoke to had come across him. Callimachi concedes that Suder “never met the other hostages,” but she says that was because he escaped before they were transferred to the same location. She confuses the timing of the events in her story: the hostages were held at the hospital in the summer of 2013, not “late in 2013” through January 2014, as Callimachi alleges. With few on-the-record sources to work with, Callimachi stretched what she had to suit her purposes.

Callimachi’s other main character in the piece is a young Belgian jihadi named Jejoen Bontinck, who was incarcerated with the journalist James Foley and the photographer John Cantlie in an Islamic State jail in Aleppo. Bontinck told Callimachi that Foley—who would later become the first American executed by the group—had converted to Islam while imprisoned, not to curry favor with his captors, but because he was a true believer:

“Mr. Foley converted to Islam soon after his capture and adopted the name Abu Hamza,” Mr. Bontinck said. (His conversion was confirmed by three other recently released hostages, as well as by his former employer.) “I recited the Quran with him,” Mr. Bontinck said. “Most people would say, ‘Let’s convert so that we can get better treatment.’ But in his case, I think it was sincere.”

Bontinck told me the same story when I interviewed him in Antwerp that September. But there were reasons to be cautious. Bontinck had been sent to the journalists’ cell in part to encourage their newfound faith in Islam. He was far from a neutral observer. Another of Callimachi’s supposed sources, Philip Balboni, the CEO of Foley’s employer, GlobalPost, wrote to me recently that he had never confirmed “this alleged conversion to Islam.” One of Callimachi’s sources among the hostages was the French reporter Nicolas Hénin, who continues to believe Foley’s conversion was genuine, but the only person to whom Foley is known to have spoken directly about his conversion was another French hostage, Didier Francois. According to Francois, Foley said that the conversion was a ruse to get better treatment.

After publication, the Foley family complained, saying that Foley was a devout Catholic. They believed his conversion must have been strategic. The Times responded by publishing a meditation on the meaning of conversions in captivity, but an editor’s note wasn’t appended to the story until January of this year, following the investigation into Caliphate. The Times acknowledged the conflicting accounts, and said that “in retrospect, this original article would have been enhanced if it had reflected more of that complexity.”

By October 2014, there was already a clear lack of rigor in Callimachi’s reporting that ought to have been addressed. Two months later, Callimachi followed up with another Page One story, this time taking aim at the U.S. policy of refusing to pay ransom for American hostages held by the Islamic State. Callimachi’s main character was a Syrian cameraman named Louai Abo Aljoud, who had been imprisoned in late 2013 alongside around twenty Western hostages in a factory in the Sheikh Najjar industrial area on the outskirts of Aleppo, where they were relocated from the hospital. Aljoud told Callimachi that the American officials he met upon his release in May 2014 were blithely uninterested in what he had to say about the prison’s location, making it sound as though the U.S. government had ignored information that might have formed the basis for a rescue mission. But Aljoud emerged from captivity nearly six months after the hostages had been transferred out of Sheikh Najjar. Callimachi acknowledged the time lag but finessed it by noting that the Islamic State “has been known to recycle prison locations.”

As Callimachi knew, or should have known, the unit of the Islamic State in charge of the Western hostages fled Sheikh Najjar completely in late December 2013, moving hundreds of kilometers to the east. Omar Alkhani, the boyfriend of Kayla Mueller, the American aid worker who was held hostage and likely killed by the Islamic State, told me recently that Aljoud’s account was wrong. Contrary to Aljoud’s testimony, the Americans interviewed anyone they could get their hands on, including Alkhani, because they were desperate for actionable intelligence. In fact, a rescue attempt in July 2014 failed precisely because the intelligence was out of date and the hostages had been moved again. Callimachi interviewed Alkhani but did not include his perspective in her story.

Several foreign correspondents at the Times complained about Callimachi’s reckless approach. Ben Smith, the Times media columnist, has reported that Anne Barnard, then the Beirut bureau chief, and C. J. Chivers, a veteran war reporter, were among the first to raise concerns. To some journalists at the paper, it looked as though Callimachi was crafting the facts to fit a narrative. Her ambition for big stories often seemed to override what should have been a suspicion that she was being sold a line. One journalist who raised concerns with a masthead editor told me that Callimachi “was so hungry, but not conscientious. She took the bait every time. I began to be convinced that this was a ticking bomb for the Times.” But nothing was done. Joseph Kahn and Michael Slackman, deputies of Baquet who had been responsible for building Callimachi’s early profile at the paper, brushed off the criticism of her work. Callimachi’s star power on Twitter was enough to buy her independence from scrutiny and elevate her into a new category of journalists who didn’t live by the same rules or standards as everyone else.

Again, it wasn’t until the demise of Caliphate that an editor’s note appeared at the top of her story on the ransom ban. “After the article was published, the Times learned that Mr. Aljoud had given inconsistent accounts of key elements of the episode to Times journalists and others,” it read. “Some of the problems with Mr. Aljoud’s account came to light shortly after publication, but editors at that time decided not to make any changes in the article.”

Caliphate was the brainchild of Andy Mills, a young producer who pitched the podcast during his New York Times job interview. His original idea was to create an audio series explaining the rise of the Islamic State, with Callimachi at its center. Mills would go on to become a producer and reporter on Caliphate. Emboldened by the success of The Daily, the paper’s morning news podcast, top editors had been casting around for an ambitious, long-form audio project. Sam Dolnick, a cousin of the publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, and an assistant managing editor who oversees multimedia projects, was Caliphate’s internal champion. Dolnick approached Callimachi about the idea, and she was enthusiastic.

Caliphate had its host, one of the world’s most famous terrorism reporters. Now all it needed was a main character. In November 2016, an analyst with the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) told Callimachi about Chaudhry. MEMRI had just published a bulletin profiling Chaudhry’s output on social media, where he had been bragging about his time in the Islamic State. Callimachi should have proceeded with caution. MEMRI is a think tank co-founded by a retired Israeli intelligence officer whose work has been accused of sensationalism. The group translates media reports from the Middle East in order to highlight anti-Semitism, conspiracy-mongering, and support for terrorism, which otherwise might go unacknowledged. MEMRI has considerable resources at its disposal, and its translations are often useful and insightful, which is why they appear in places such as the Times. But the think tank also risks amplifying the propaganda of fringe extremists without regard to whether their claims are credible or real. (MEMRI did not respond to a request for comment.)

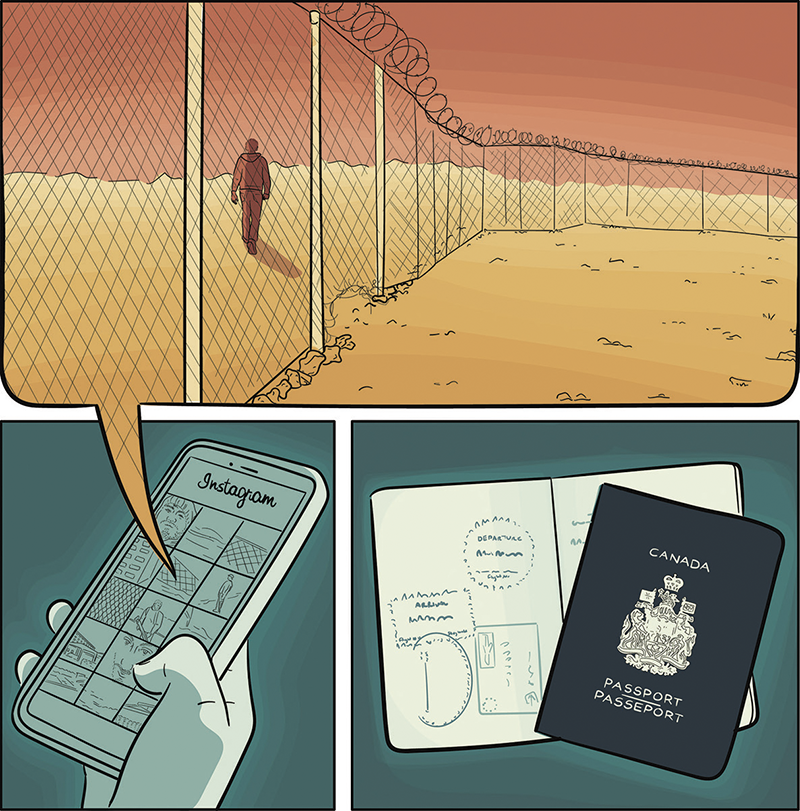

Within a few days, Callimachi and Mills were on a plane to Toronto to meet with Chaudhry. What he told them there became the narrative backbone of Caliphate. In Chapter Three, Chaudhry explains how, moved by the suffering of the Syrian people and inspired by the rise of radical Islamism, he ducked under a chain-link fence at the Syrian-Turkish border to enter territory controlled by the Islamic State. By Chapter Four, he is shooting a prisoner in the back of the head. In Chapter Five, he is called upon to pass judgment on a drug dealer, a rite of passage he had to complete in order to join a battalion called Rayat al-Tawheed, which he had learned about online. Chaudhry told Callimachi that stabbing the drug dealer through the heart marked his moment of disillusionment, the moment he resolved to quit the Islamic State.

The Caliphate reporting team had doubts about Chaudhry’s story at least two months before the show started airing. Early in 2018, Callimachi discovered that the stamps in Chaudhry’s passport didn’t match the timing of his story. According to one Times staffer who worked on Caliphate, Callimachi didn’t realize the gravity of the problem until she presented her work to Slackman, who told her to find corroboration. Callimachi was responsible for fact-checking the whole series, drawing on the paper’s expertise but not really beholden to it, sending out tidbits for piecemeal confirmation in a way that didn’t get to the heart of the story’s fundamental unlikeliness. Callimachi called some of the paper’s best national security correspondents, who dutifully tapped their official sources and found evidence that, yes, Chaudhry was on a terror watch list and under investigation by the Canadian authorities as a suspected terrorist.

When Callimachi confronted Chaudhry about his passport, he admitted that he had lied about the timeline of his trip. Instead of entering Syria in February 2014, as he originally claimed, Chaudhry said he traveled to the country after the declaration of the caliphate, sometime in late 2014 or early 2015. Rather than get to the bottom of things, the Caliphate team simply integrated their doubts into the podcast. In Chapter Six, there is an abrupt shift in tone:

mills: I, I hate to be the one who says this, but what if—what if this turned out to be the weirdest case of catfishing?

callimachi: What is catfishing?

mills: That’s, like, when somebody is online pretending to be someone else, and then begins to rope people in real life into intense situations, usually romantic, with that person’s invented persona.

callimachi: Yeah.

mills: But if this turns out to be some sort of fantasy that he’s living out, this is the most strange and profound fantasy I’ve ever heard of.

It was a fantasy—an illusion created by social media. Reporters, officials, and experts were passing around the same information about Chaudhry, which seems to have originated with the MEMRI report on his Facebook and Instagram feeds. More digging would have led them to the truth. By the time the series aired, the Canadian government already had information that suggested Chaudhry’s account was utterly bogus, as the Times reporter Mark Mazzetti discovered when he was assigned to investigate the story as part of the paper’s review last year. Mazzetti found that Chaudhry had spent a huge amount of time online studying Islamist propaganda. That didn’t make him a terrorist.

In the months since the Times issued its apology, one cause of the Caliphate fiasco has been entirely overlooked: the role of internet-led reporting. By the time Callimachi started on the Islamic State beat in 2014, it had become almost impossible to travel through Syria. Bashar al-Assad’s government issued few visas to journalists, and the ones they did supply were often given to sympathetic reporters. And as the uprising transformed into a civil war, reporting from areas outside government control became fraught with danger. Long before the rise of the Islamic State, rebel groups and Islamist militias had taken to kidnapping Western journalists for ransom. In February 2012, Anthony Shadid, the Times’s Beirut bureau chief, died of an acute asthma attack while reporting from rebel territory in the northwest. His death, along with that of the Sunday Times reporter Marie Colvin, who was killed six days later by government shelling, led editors to think twice about sending journalists to Syria.

Since reporting on the ground was so difficult, journalists based in Beirut began cobbling together stories with the help of social media. Reporters such as Callimachi and myself were plunged into a dangerous new world of online chatter, in which we were outnumbered by highly opinionated activists, analysts, and anti-extremism experts. Hardly any of them had been to Syria since the uprising began; a good many seemed to be getting their information mainly from Twitter.

Callimachi was prolific on social media, chatting with Islamic State sympathizers, retweeting support for her work, and supplying information about her background. Two journalists who knew her at the time told me that she was perennially breaking off conversations and interviews to check WhatsApp and Twitter. In a 2018 interview with The Cut, she described her morning routine:

I wake up when my alarm goes off and the first thing I do is I check email. I then check the DMs I’ve received on Twitter, and then I go to Telegram. This is the encrypted app where ISIS chat rooms are located.

Callimachi’s fluency with social media was one of her strengths. The rise of the Islamic State was an era-defining story, and Callimachi was one of the first reporters to take it seriously. Here was a new kind of millenarian Islamism, both nimble and hierarchical, and inspiring enough to a small minority of disaffected young Muslims in the West to launch a string of terror attacks. The attention Callimachi paid to jihadi social media, where the group was sharing the glossy propaganda that became key to its appeal, gave her an edge on other reporters.

But the new reliance on social media led to high-profile errors across the board. Take the case of Ibrahim Qashoush. According to media reports, Qashoush was a protest singer from Hama who had his throat cut and his vocal cords ripped out by government agents in 2011. Almost every major global newspaper and TV station did a story on the killing, and it became one of the defining atrocities of Syria’s uprising. “This is a purely criminal act,” Omar Idlibi, a spokesperson for the Local Coordination Committees of Syria, a decentralized network of opposition media outfits, told the Associated Press. “They executed him.” In a rare interview with Assad in December of that year, Barbara Walters confronted the Syrian president with the story; he seemed to have no idea what she was talking about.

I discovered that the facts as presented were all wrong. As I reported for British GQ, the singer was a courageous young man named Abdulrahman Farhood. He was alive and well, living in Europe; I spent several days hanging out at his apartment listening to him sing. Ibrahim Qashoush, on the other hand, was a disabled security guard at a local fire station in Hama who’d likely been killed by rebels because they suspected he was a low-level snitch for the Assad regime. As far as I know, none of the reporters who’d filed stories on the killing had been in the country at the time, except for the Times’s Anthony Shadid, who interviewed Farhood in Hama and found out the truth. But Shadid’s story got buried in an avalanche of misinformation.

Although the Times got that story right, the paper had its share of missteps as it began to rely more on remote reporting like everyone else. Six weeks after the flurry of stories about Qashoush, the Times ran a story informing its readers that the attorney general of the province, Adnan al-Bakkour, had resigned in order to protest the killing and arrest of demonstrators, and to denounce the widespread torture occurring in state prisons. As proof of the story’s importance, the Times noted that al-Bakkour was “the highest-level official to quit over the brutal crackdown.” Opposition media activists released a video of the bespectacled lawman in a neatly pressed gray suit, solemnly reading out the reasons for his defection. Hundreds of people had been buried in mass graves, he said, and the Syrian Army had torn down houses while residents were still inside.

This is what really happened: al-Bakkour had been on his way to work when he was kidnapped by armed rebels who’d been pressuring him to resign, and who forced him to make several videos under duress. By the time I was able to get in touch with his wife, Jihan, years later, she had long been a widow. “The execution was by bullet,” she told me. The family found out about al-Bakkour’s murder from people in rebel-held villages. It was odd that a man who’d so publicly taken the rebel side should never be heard from again, but the world had moved on, and no one bothered to ask questions. “Most of the media are publishing news without any proper investigation, without knowing if it’s true or not,” said Jihan. “It’s not important to me. I’m used to these things.” Rami Abdulrahman, director of the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights and one of the most trusted sources on the conflict, confirmed that the version of the story that had appeared in the papers was “one hundred percent bullshit.”

The stories about Qashoush and al-Bakkour had a great deal in common. They’d both been filed by reporters in Beirut who had reached out via telephone or social media to opposition activists in Hama—specifically the Local Coordination Committees. The LCC spokesperson who told the Times that al-Bakkour was in hiding went by the name Omar Idlibi. This, presumably, was the very same Omar Idlibi from the LCC who’d puffed up the lie about Qashoush in an AP interview. A month later, he was excited by the possibilities presented by al-Bakkour’s defection. “He knows every single detail about the crimes committed by the authorities,” Idlibi told a reporter from the Times. With the information he had, he assured the reporter, “we will be able to take the regime to the International Criminal Court.”

In 2018, I sent a corrected version of the Adnan al-Bakkour story to David McCraw, a lawyer for the Times to whom some family members of Islamic State hostages had complained in 2014 about Callimachi’s reporting. He agreed it was worth revisiting. But the paper wasn’t interested in running my reporting. I received an email from a Times Magazine editor saying the story was no longer topical.

Reporting online, it was hard to know whom you were dealing with. Callimachi’s most celebrated article in 2015 was another Page One feature called isis and the lonely young american, which told the story of a troubled woman in Washington State named Alex, who had fallen under the sway of Islamists online. But there was something unsettling about the article. Despite some deft narrative footwork, there was no real evidence that Alex had ever been in touch with anyone from the Islamic State. Alex had communicated with someone on Twitter who said he was fighting for the Islamic State in Syria, but that couldn’t be confirmed. For the most part, Alex’s new online friends were a combination of Salafis and Islamic State fanboys. Callimachi identified one Twitter account Alex had communicated with as having been “in regular contact with ISIS fighters,” but, just as in Caliphate, this was on the say-so of MEMRI rather than her own reporting. The article was careful to acknowledge that the Islamic State’s recruitment effort “is vastly extended by larger rings of sympathetic volunteers and fans who pass on its messages and viewpoint,” but in doing so it muddied the distinction between online Islamic State sympathizers with no formal connection to the organization and the group itself—the same approach that would prove Callimachi’s undoing in Caliphate.

Mubin Shaikh, an antiradicalization expert, came across Alex online around the same time. Alex suffered from complications related to fetal alcohol syndrome and, Shaikh told me, was spending around eighteen hours a day on the internet. When I asked if the people she met there might have been sympathizers rather than militants, he agreed it was possible. Sometimes, he noted, it’s difficult to tell the difference.

Announcing the results of the paper’s internal investigation in December, Baquet admitted that Caliphate had been an institutional failure that went beyond any single reporter. They had treated the podcast like a story in the daily paper, relying on the reporter to check her own work, instead of like a major magazine feature or investigation, which are more carefully vetted. “I did not provide that kind of scrutiny, nor did my top deputies with deep experience in examining investigative reporting,” he told the staff. By the time problems reached the desks of high-ranking editors, the project had momentum, and it was allowed to move forward despite them. Callimachi was “a powerful reporter whom we imbued with a great deal of power and authority,” Baquet said in an NPR interview the same day. “She was regarded at that moment as, you know, as big a deal ISIS reporter as there was in the world. And there’s no question that that was one of the driving forces of the story.”

Internally, the apology only intensified the disappointment many felt with the paper’s leadership. In the days before the public recantation, Kahn called a number of reporters who had previously raised concerns about Callimachi’s work. His tone was apologetic. He and Dolnick then convened a video call with a group of between fifteen and twenty reporters and editors to discuss the findings. The mood was funereal. The Times had worked hard to build up expertise in the region, someone pointed out, which editors then proceeded to ignore; the result had been to undermine the collegiality and openness that characterizes good editorial decision-making. According to Erik Wemple, a columnist at the Washington Post, Chivers read a statement he had prepared that excoriated top editors for ignoring and maligning those who had raised red flags. “Warnings were not just dead letters,” he said. “They became a basis to impugn people personally and professionally.” One journalist invoked the spirit of Anthony Shadid. Kahn seemed chastened.

Callimachi was reassigned to cover education, and an experienced editor, Cliff Levy, was brought in to oversee the audio department, but the imbroglio seemed to call for a broader reckoning. The Times, already divided over controversial resignations such as that of the editorial-page editor James Bennet, was struggling to hold its newsroom together. Staffers and readers started to complain that Callimachi had been the only person to be penalized. Accusations of inappropriate workplace behavior by Mills in a previous job, detailed in a 2018 article in The Cut, began to resurface online. In February, he resigned. I spoke to him shortly thereafter, and he told me that the Times’s reinvestigation of Caliphate found no journalistic malpractice on the part of the audio team. Callimachi and Mills had brought all their findings to Dolnick, Slackman, and Matt Purdy, who heads investigations, and they had signed off. In a meeting during the internal review, Baquet had told Mills: “I won’t let you blame yourself.”

Nevertheless, no one outside the Caliphate team has faced consequences. Dolnick, as the executive in charge of audio and a major force behind Caliphate, clearly failed to provide the necessary editorial oversight, but the fact that he is a Sulzberger heir may have shielded him from scrutiny. The focus stayed on Callimachi.

This is a pattern the Times has repeated. The paper’s system for anointing certain journalists as stars has long been the cause of controversy; Judith Miller’s celebrity status at the paper was one explanation given for her dramatic rise and fall following her credulous reporting about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. Callimachi came aboard at the beginning of an era in which journalists were becoming brands on social media. Thrown into reporting from afar on a region she knew little about, she foundered, but senior editors at the paper were too pleased with the results to care. A succession of senior editors—Kahn, Slackman, and Dolnick, among them—were happy to nudge her toward blockbuster, character-driven pieces, culminating in Caliphate. The pressure was to produce and produce, even at the expense of spreading the reporting thin. “Everything in this story leads to the internet because that’s where it all began,” said one Caliphate staffer. “It plays a key role in kingmaking, which is at the root of the problem that the Times is now dealing with. The incentives of the internet mean that the Times keeps wanting to do this.”

Syria might have been considered an outlier. The war was such a dangerous and expensive conflict to cover that it became too difficult to put journalists on the ground. But the murkiness of its information wars seems, in retrospect, like a rehearsal for many of our current concerns about “fake news.” We often talk about disinformation as a strategy used by antagonists—Russians, the “alt-right,” Donald Trump—who deliberately seed lies and conspiracy theories. But the truth is that bad information is everywhere. As foreign bureaus become a thing of the past, there are fewer reporters on the ground. Journalism is supposed to be a labor-intensive business, one that requires digging up facts. Today, there’s a glut of information out there for free, but most of it has been put there for a reason. The New York Times’s reporting on Syria is better than most—probably the best there is—and the paper gets things right far more often than it gets them wrong. But strong journalism requires on-the-ground expertise and skepticism as much as great characters and slick narratives. The alternative is a new age of ignorance in which media companies offer their platforms to anyone with an axe to grind.

While awaiting trial for allegedly perpetrating a terrorist hoax, Chaudhry is helping out at his family’s shawarma restaurant. On New Year’s Eve, I sent him a WhatsApp message asking whether he’d like to talk. “I didn’t lie about anything,” he wrote back. “The fact is I’ve won, I got away with jihad and now EVERYONE IS TRYNA SAVE THEIR ASS INCL. CANADA.” Callimachi still thinks there’s a chance he’s telling the truth, believing that the hoax charge could be a complicated play by the Canadian authorities to force him to admit to his crimes. The pair apparently remain in touch.