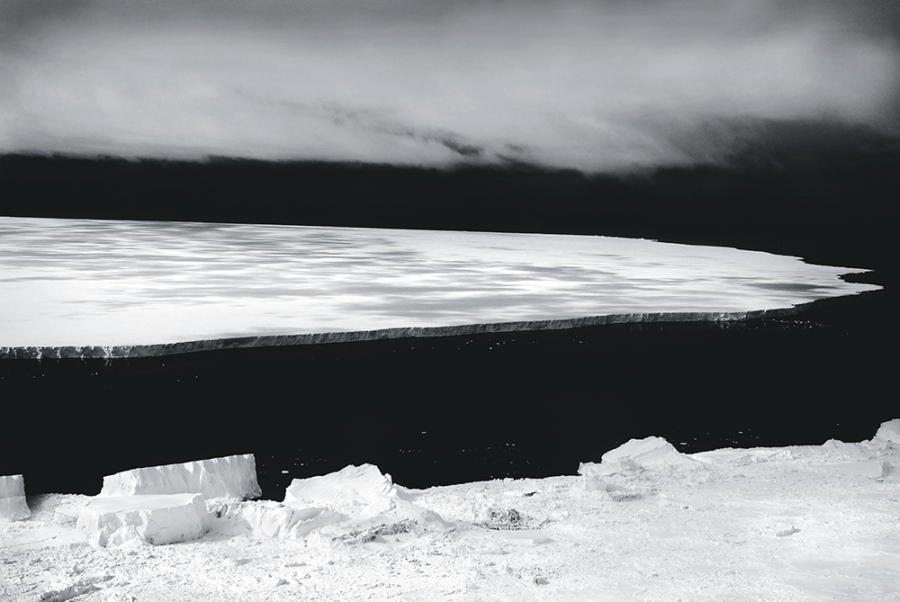

“Cape Crozier (B15 Iceberg),” by Joan Myers © The artist. Courtesy Andrew Smith Gallery, Tucson, Arizona

Discussed in this essay:

Lean Fall Stand, by Jon McGregor. Catapult. 288 pages. $26.

In the background of Lean Fall Stand, the English writer Jon McGregor’s new novel, there’s an aspect of British culture that might seem strange to outsiders: the country’s obsession with polar exploration as a test of national character. The obsession runs back through the nineteenth century, but at its center is Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who reached the South Pole in January 1912, only to find that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen had arrived a month earlier. Scott and his four companions then died on the return journey in a style that spoke directly to the British love of heroic failure and stoic understatement. So indelible were the frostbitten Lawrence Oates’s last words as he left their tent to vanish in a blizzard rather than burden the others—“I am just going outside and may be some time”—that the men’s status as noble victims of bad luck was rarely questioned. It wasn’t until 1979 that a debunking biographer, Roland Huntford, began to steer conventional wisdom round to the idea that Scott hadn’t been a particularly well-prepared or competent explorer.

Looking back, it’s somewhat surprising that Scott’s renown made it past the First World War. It’s easy, now, to see analogies between the hidebound military leaders who supervised the disaster in Europe and the attitudes that doomed Scott’s party. Dogsledding and Inuit survival techniques worked well for the Norwegians, but there was a feeling, shared by Scott, that hauling your supplies on a heavy sled yourself was the only way for Englishmen to comport themselves at the Poles. It would be a valuable display of self-reliance, one of Scott’s men remarked, “in these days of the supposed decadence of the British race.” Scott’s chief backer, Sir Clements Markham of the Royal Geographical Society, was similarly attached to the “man-hauling” system of the 1850s, and wasn’t a fan of the modern world in general. For Markham, scientific research was just a pretext. The real utility of polar expeditions, he wrote, lay in the “opportunities for young naval officers to acquire valuable experiences and to perform deeds of derring doe.”

In other words, boyish, retrograde fantasies played their part in the heroic age of Antarctic exploration. As Francis Spufford put it in a study of British polar imaginings—a book called, as it had to be, I May Be Some Time—there was a “water-marking of unreality” around the whole enterprise. Along with the pure abstraction of racing to an invisible coordinate in an uninhabitable wilderness, this made the Scott story prime material for mythmaking, and no one understood this better than Scott himself. As he and his two remaining men froze to death, he went on a fantastically eloquent writing jag, defending his management of the expedition, pleading for pensions for their widows, and saying his goodbyes. The last page of his journal—recovered by a search party eight months later—ends with a scribbled postscript: “For God’s sake look after our people.” Scott’s grasp of logistics might have let him down, but his grasp of language didn’t, and he was able to set the terms by which his story would be told.

Lean Fall Stand opens in a remote corner of Antarctica toward the end of the 2010s as three Englishmen find themselves in a tight spot. Two of them, Thomas Myers and Luke Adebayo, are postdoctoral researchers on their first visit to the continent. The third, Robert Wright, known to his colleagues as Doc, is a field guide with the title of general technical assistant, a veteran of thirty-three seasons there. They work for something called the Institute, based in Cambridge, a fictional outfit that’s not to be confused with the Scott Polar Research Institute at the University of Cambridge. On an afternoon “given over to recreational activity”—the language is that of the self-justifying field report that Doc will soon be composing in his head—they have gone down to the shoreline “with the principal intention of facilitating Thomas’s photography interests.” Luke waits by his snowmobile. Thomas walks out on the sea ice. Doc climbs a nearby promontory to give Thomas’s shots a sense of scale. Then a storm sweeps in, reducing visibility to zero and knocking each of them flat.

In the carefully choreographed sequence that follows—perhaps the most stressful opening of an upmarket English novel since the hot-air balloon accident that begins Ian McEwan’s Enduring Love—McGregor uses flashbacks to fill the reader in on the workings of this small group. Low-level misunderstandings have permeated their time at Station K, a field hut hundreds of miles from the nearest base. The two Antarctic greenhorns are GPS technicians. Their job is to improve the mapping of this portion of the world, which Doc remembers people doing with theodolites, on foot. He discourages the pair from speaking of mistakes, insisting that they use the word “anomaly” instead. (Later, his wife will use the same word to describe their marriage.) The two technicians are millennials who say things like “Lol out loud, mate,” and amuse themselves with ribald innuendos about Doc’s suggestion that they debrief one another every night. The Antarctic term for rations, “manfood,” amuses them, too. Doc, who’s impervious to irony, eventually works out why they’re asking him if the term isn’t “problematic”:

“I think you’re reading too much into it.”

“Do you?”

“I mean, we’ve actually had some excellent women working for the Institute, in more recent years. Some of them have even worked as GTAs.”

“Very modern.”

“You wouldn’t know the difference, with some of them.”

“You wouldn’t know the difference?”

“No, not at all. Honorary men, effectively.”

In another excruciating scene, Doc turns to Luke—who, it’s been made clear indirectly, is of Nigerian descent—and asks him where his family are from. Luke tells him they’re from South London. Doc presses him: “Where are they from originally, though?” Luke shuts him down, snapping that they’re from Norway. Doc responds with literal-minded incredulity.

These “OK, Boomer” moments don’t affect their working relationship. Doc is an excellent field guide. The younger men are slightly self-conscious about standing on mythic ground: even the phrase “unloading the stores from the hold” gives Luke a covert thrill. In the evenings, Doc reminisces—a bit repetitively, if they’re honest—about old Antarctica hands with names like Planky Carruthers, or expands on his dislike of modernities. Life in Cambridge is all “gas bills and nonsense”: “new roads, new estates, buildings knocked down and thrown up.” In Antarctica, “nothing changes.” The land has “purity; simplicity. It’s difficult to explain.” Asked how his wife feels about all this, he says they have “an understanding.” Thomas notices that Doc starts drinking quite early, and that he rarely charges the satellite phones, apparently regarding their use as cheating. But “he obviously knew his stuff. He would know how to get them out of a difficult situation.”

When the storm rolls over them, the situation gets difficult very fast. Their problems understanding one another on a social level are replaced by more urgent communication problems. Thomas can’t find his radio, and Doc is too busy trying not to get blown off a cliff to answer his. Worse, a brief lull reveals that the storm has broken up the sea ice. Luke sees Thomas drifting out into the bay on an ice floe. Then everything goes white again. Now we cut back to Thomas’s point of view. He has found his radio, and has noticed that a leopard seal, if not quite circling, is definitely “maintaining a presence.” They need to call in airborne help, but no one has a working sat phone, and Luke isn’t sure he’ll be able to find the hut, where there’s a high-frequency transmitter. At this point, Doc’s voice comes over the radio. “Stand by for a brief quickening,” he says. “Situation upstate.” This opening section of the novel ends with a passage written in close third person, dipping in and out of Doc’s interior monologue, as he crashes into the hut, then fails to summon help:

He looked at the radio. There was something he needed to do. He crossed the floor of the hut to the window. It was a long way. Everything leaned over to the right. The floor rose and fell. The glass was cold against his face. The weather was solid. They were good lads but this was their first season south. They didn’t yet have that indistinct. The cold was glass against his face. It was not unpleasant. He leaned into it. He waited.

He has had a stroke while battling the storm, and aphasia is rapidly taking away his language.

Born in 1976, Jon McGregor has won the sort of admiration worth having—his fans include George Saunders, Yiyun Li, Teju Cole, and Hilary Mantel—with an unusual combination of self-effacing craftsmanship and formal experimentation. He’s also an exception to the general rule in English literary culture that the center of the universe is in or near London. He grew up in Norwich and Thetford, studied in Bradford, and now lives and teaches in Nottingham. His first novel, If Nobody Speaks of Remarkable Things—which was published in 2002, and made the Booker longlist—describes a single day on a single street in a suburb of an unnamed, deindustrialized, northern English city. Such cities are often stereotyped as unglamorous, and reviewers have tended to highlight McGregor’s interest in “ordinary people.” It’s meant as praise, but as he has complained from time to time, it involves assumptions about some people being more ordinary than others. It could be construed as code for “provincial people,” or “people who aren’t comfortably middle class.”

The late critic Eileen Battersby took a different approach in a remarkably uncharitable review of McGregor’s first novel for the Irish Times. It was “a pretentious parade of heavily intense gestures,” she wrote, accusing McGregor of archness, boringness, schematic plot construction, aiming for cinematic rather than novelistic effects, and overwriting. McGregor took some of these strictures on board, and won Battersby round with the plainer style of his third novel, Even the Dogs—an account, published in 2010, of the lives of homeless heroin addicts and alcoholics in an unnamed city in the Midlands—which owed something to Raymond Carver, and to the Scottish writer James Kelman’s use of a vernacular speaking voice. But he had the sense to ignore her when it came to the qualities that made his first novel stand out. His work maintains an interest in nonconventional storytelling that isn’t obviously indebted to any particular modernist tradition; an attention to the way politics plays out in the lives of characters who aren’t defined by their regional, ethnic, or class identities; a fascination with freeze-frames, fast-forwarding, and other narrative manipulations of time; and an emphasis on large ensemble casts rather than a handful of individuals.

His best novels also use conspicuously unanswered questions to lodge themselves in the reader’s memory. They’re the kind of books you find yourself thinking about at odd moments, months or years later. Even the Dogs begins with the discovery of a corpse and ends with an inquest that doesn’t settle much, although the reader can piece together an explanation for a wave of overdoses in the city, and the story of the dead man’s descent into alcoholism, caused, in part, by an undiagnosed brain injury from the Falklands War. It’s narrated by a ghostly compound “we,” which functions sometimes like a chorus and sometimes like a description in a screenplay. Soon, distinct voices make themselves heard, and a set of characters comes into view: Robert, the dead man; Danny, a heroin addict from London; his tough friend Mike, a schizophrenic from Liverpool; Laura, who turns out to be Robert’s adult daughter; and so on.

Each of these characters is carefully particularized—Steve, an alcoholic army veteran, always remembers to lay his socks out to dry before he passes out—and it’s usually possible to deduce a horrific personal backstory. The deindustrialization and unemployment associated with Thatcherism are there, too, if you care to look for them, but there’s no sense of points being hammered home, or, for that matter, of the frequent shifts in perspective and chronology being pursued as formalistic ends in themselves. The novel’s most audacious set piece—a woozy seven-page sequence that tracks the parallel journeys of a wounded British soldier and a shipment of heroin from a poppy field in Afghanistan’s Helmand province to the British Midlands—has the unsettling beauty and fluidity of an Adam Curtis montage (minus the portentous voiceover). It isn’t a comforting book, but McGregor uses great resourcefulness and empathy to coax a variegated set of voices from a monochrome landscape of “alleyways and open garages, railway arches, tunnels, derelict buildings, the backyards of offices and pubs.”

Reservoir 13, published in 2017, has a wider social canvas and tonal range, but in one sense it’s even more uncompromising. It begins like a crime novel, or a drama series descended from Twin Peaks, with searchers combing the moors for Becky Shaw, a thirteen-year-old girl from London who has disappeared during a family walk in the Peak District—an upland region between Manchester and Sheffield popular with hikers, and riddled with abandoned mines and quarries as well as ravines and bogs. (The novel’s evocation of place involves a feeling for the way this apparently pastoral landscape has been shaped by industrial activity, starting with the reservoirs of the title.) It’s possible that Becky has had an accident involving one of these features, but it’s also possible that someone has kidnapped her, and in the opening chapter, which covers a year, we watch the investigation’s effect on the village. Twelve yearlong chapters follow, and the incident fades into memory. We never find out what happened to Becky Shaw.

A danger with this strategy is that the reader will feel cheated, and some do. The frustration is all the sharper thanks to the novel’s powerful illusion of reality: you start believing in the characters and the setting so much that it’s hard not to imagine Becky’s fate would be determinable if you could only tilt the perspective by a couple of degrees. There’s a hypnotic annual cycle of lambing and cricket matches and New Year’s Eve fireworks, but also a convincing impression of time passing in a linear way. We watch the teenagers who knew Becky grow up and leave for university, while other characters pair up or divorce or die or have passive-aggressive feuds about vegetable gardening. Male violence is always hovering near the edge of the picture, but there are moments of warmth and humor too, and the writing is unobtrusively extraordinary. It uses plain, precise sentences and a large helping of the passive voice to convey a kind of collective consciousness, one that encompasses the natural world as well as local gossip:

In the beech wood the foxes ran through the night. The cubs were now as big as the adults and were striking out on their own. They would soon be seen as competition. There was play but it took on a fierce edge and there were fights that ended in blood. The edges of the territory were understood. In the evenings now the noise of people talking outside the Gladstone was louder on account of the smoking ban, and no matter how many notices Tony put up he still had complaints from the parish council. Some people had no idea how their voices carried.

The flavor is difficult to get across in a short quotation—a typical paragraph is two or three pages long, its crosscuts held together by a steady rhythm—but, somehow, the idiom never seems gimmicky, just as the mystery of Becky’s disappearance charges every detail with potential meaning in a way that somehow bypasses “heavily intense gestures.” It’s a haunting book.

There are sentences in Lean Fall Stand that, apart from a few small details, could have come from Reservoir 13: “There was movement in the water, and the sky darkened above the glacier. A weather system moved in from the ridge.” Like those of the earlier novels, the new book’s cardinal themes turn out to be very different from those suggested by its opening. But it’s a jumpier, less cohesive story, with different styles and texture on offer, and a reconfigured cast in each of its three main sections. Doc’s wife, Anna, who calls him Robert—as the novel does once he’s left Antarctica—becomes the focal character in the middle section, in which Robert has been airlifted to a hospital in Chile and can only say things like “Wh, whuh. Whuuuh.” On top of Robert’s loss of speech, she has to come to terms with the expectation that she’ll uncomplainingly become his caregiver once he’s well enough to return to Cambridge. The novel’s final section rotates among three women, as the first section initially rotated among three men. The women are Anna, Amira, and Liz; the last two run a support group for aphasic stroke victims, where Robert slowly learns to articulate his story, after a fashion, to others and himself.

Anna turns out to be a climate scientist, a specialist in oceanographic modeling. She and Robert met in Cambridge in 1984, when he was losing interest in his PhD and considering a job with the Institute instead. She liked the way he asked questions and listened to her answers. “Later—too late—she’d watched him performing this listening for other people and realised it was something he knew how to turn on and off.” They married because it was convenient. She could get on with her research, and “they could put off having children until much later, if at all.” Sooner than expected, however, they did have children, who, in time, resented their father’s absences. Then there was the matter of Tim Carruthers, aka Planky, Anna’s best friend’s husband, who froze to death in a crevasse while out on an unnecessary joyride with Robert. Anna and Robert both think back to Tim’s funeral. In Robert’s recollection, the women were rather difficult about it:

At the funeral Anna telling him she knew this was what he wanted. What did she mean, he’d asked her; what was it he wanted? All this. White lilies in vases, varnished coffin, colleagues in funeral black, lonely widow stooping low. The heroic death. For God’s sake look after my people. All that. The organ playing, and the sunlight streaming through the high chapel windows. I’d prefer to be buried down south, he told her. It was a joke but it went unappreciated.

Now Robert’s people are being asked to do the looking after, and for all his earlier talk of “sacrifices to make,” and “how important his work was,” it’s Anna who’s having to step back from an academic project that’s meant to be informing the next report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. By comparison, Robert’s work in Antarctica looks like little more than a pretext for deeds of derring-do. Anna isn’t even sure she wants him to come home.

On one level, Lean Fall Stand is concerned with the idea of heroism, and what McGregor has called “the heroism of care.” In the opening section, Robert’s masculine ideals—complete with a life-threatening nostalgia for older ways of doing things, and a feeling that the younger men are insufficiently self-reliant—lead to disaster, and Thomas doesn’t make it back from Antarctica alive. In the closing section, Robert can take charge of his identity again thanks only to the communal endeavors of the female therapists and caregivers. This would seem to offer Anna a somewhat restrictive model of female heroism, so McGregor is careful to make her a complex character, ambiguous in her responses, withdrawn, and as bad as Robert is at reading social cues. When Luke lies to protect Robert during the inquest into Thomas’s death, it doesn’t occur to her that this might be a moral problem.

Robert, however, is a simpler character. Until aphasia makes his thoughts a mystery, he comes across as the sort of person who’s chillingly exposed in early John le Carré novels: an emotionally evasive Englishman who has given all his loyalties to the Institute and to a dream of adventure. In the last third of the novel, McGregor constructs a moving, well-observed drama of rehabilitation around him. There are some astonishing technical feats. As he did in Even the Dogs, for example, McGregor stealthily teaches you to recognize the characters’ verbal tics, so that, in the climactic support-group sequence, you’re able to follow interactions between the aphasic patients through the different kinds of word salad they produce. But there’s always a troubling undertow. It wasn’t just because of his stroke that Robert didn’t call in air support in time to save Thomas. He tried to rescue him instead, nearly killing himself and Luke, to conceal his earlier errors. “Whether he didn’t have the words or he didn’t want to use them was impossible to tell, now,” Anna thinks at one point.

Throughout the book, McGregor returns to language’s incommensurability to experience. It’s iterated obsessively in many different ways, from the problem of describing the Antarctic landscape to the prose poetry spoken by the fluent aphasics in Robert’s support group. “Doc Wright kept trying to tell them things, but his words weren’t getting through,” McGregor writes of the group’s noisy flight to Station K at the beginning of the story. On almost any given page, there will be a misunderstanding, a misreading of tone, a joke that doesn’t land, or someone “searching for the right words.” “No hablar,” a nurse explains in Chile. “Sin palabras.” Anna doesn’t speak Spanish but gets what she means. When the support group stages a trivia quiz, question nine is: “Who was the first man to reach the South Pole?” One man says, “Scott! Great Scott!” Another speaks a string of resonant nonsense. Robert can only say, “Am, am. Am.”

It’s easy to imagine how McGregor might have arrived at this theme as a means of connecting the Antarctica material to the aphasia material. Whether or not it completely works, and whether or not you can sustain momentum while going from ice floes and leopard seals to a support group in Cambridge, the eerie withholding of moral judgment makes Robert’s failure of character difficult to forget. The novel ends with a flashback to Robert in Antarctica moments before the rescuers arrive. Almost completely wordless, unable to remember his own name or “bring to mind the people who would miss him when he didn’t get home,” Robert feels an ecstatic, almost pantheistic sense of oneness with the land. Something has gone wrong, he knows, but with equal certainty he feels that everything is as it ought to be. It’s a sign of McGregor’s skill, and his unforced sense of the mystery at the heart of things, that the novel leaves the reader feeling much the same way.