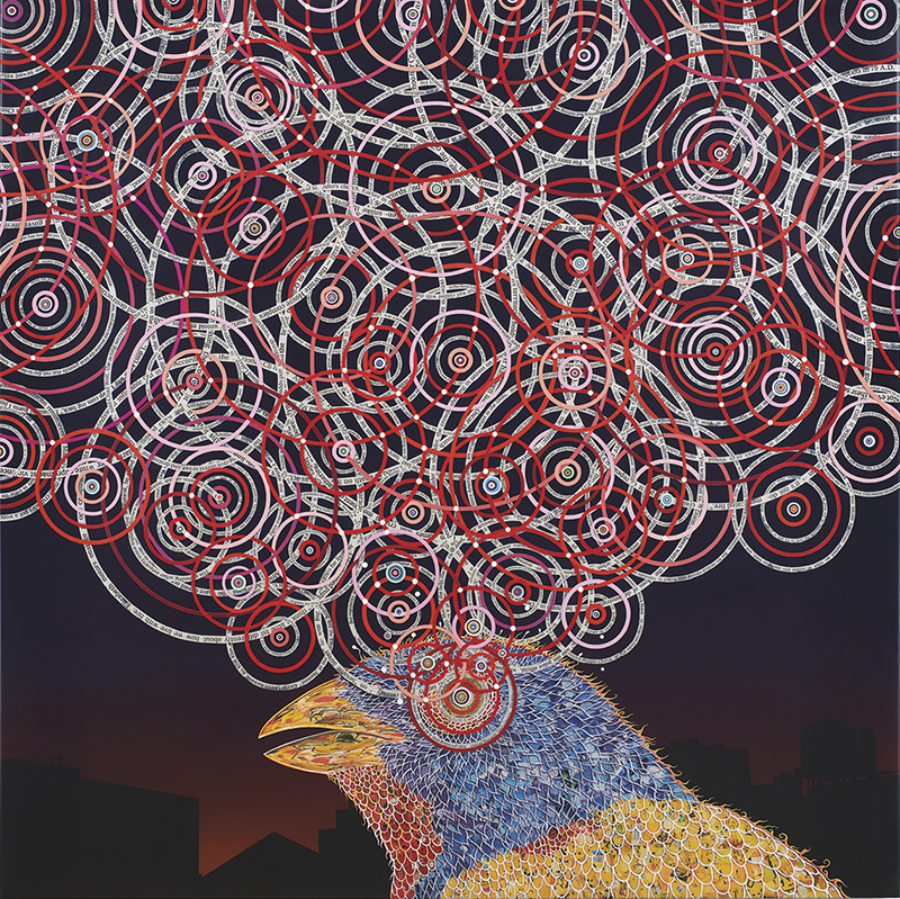

Untitled mixed-media artworks, 2020, by Fred Tomaselli © The artist. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York City. Photographs of the artworks by Phoebe d’Heurle

In 1943, after being interrogated by Vichy police officers who suspected him (rightly) of conspiring to rescue Jews from the occupying Nazis, a French clergyman named André Trocmé stepped into the open air with a revised view of the human condition. “Before he entered that police station in Limoges, he thought the world was a scene where two forces were struggling for power: God and the Devil,” writes one of his chroniclers. “From then on, he knew that there was a third force seeking hegemony over this world: stupidity.”

Trocmé’s eureka was by no means unique—his German contemporary and co-religionist Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote that stupidity (or “folly,” depending on your translation) was “a more dangerous enemy of the good than malice”—and it still rings true today. From the troglodytic inanities of entertainments such as the Instagram account Girls Getting Hurt (894,000 followers) to the pyrotechnic disasters of gender-reveal parties, stupidity is everywhere we look, not least of all in those who look for it everywhere but within themselves.

My own Trocmé moment came with a photo in the New York Times of an angry crowd protesting the tyranny of face masks in the midst of an “exaggerated” pandemic, an ominous prelude to the storming of the Capitol the following year to overturn a “stolen” election. As luck would have it, the antimask protests were taking place at the same time that my wife was reading about England during the Second World War, so there was this repeated dinnertime comparison of the prodigious sacrifices made by bombed-out Londoners with those that peacetime Michiganders found insufferable enough to justify calling up the militia. “Delusional,” “obstinate,” and “perverse” seemed woefully inadequate descriptors, and stupid regrettably unkind, but there it was. What else could you call it?

“Stupid” doesn’t mean unintelligent or even uninformed. The political philosopher Eric Voegelin was closer to the mark when he defined stupidity as a “loss of reality.” It’s possible to take Voegelin’s definition a step further and say that stupidity is a denial of reality to the degree that one’s own survival, to say nothing of the survival of others, is imperiled. “Too dumb to live,” we might say, summoning metaphors of dodo birds and dinosaurs, creatures who may not have been especially unintelligent but who owe their reputations as lamebrains in large part to their extinction. Stupidity is oblivious to negative consequences; it falls into a pit. Gross stupidity invites negative consequences; it looks for a pit. There’s an element of willfulness to it: let the oceans rise, let the virus rage, you can’t scare me. Socrates held that human beings do not knowingly act against their best interests; perhaps his wisdom made it hard for him to imagine a human being who could say, “To hell with my best interests, and screw Socrates too.” A willful loss of reality, however death-defying it may appear, is never far from a wish for death.

The widespread stupidity that pinhead populism and COVID-19 have brought to the fore goes far beyond the disdain for intellectuals that has been a current in American culture since the nation’s inception. For a sense of how far, consider this curious passage from Richard Hofstadter’s 1963 Anti-intellectualism in American Life:

It would . . . be mistaken, as well as uncharitable, to imagine that the men and women who from time to time carry the banners of anti-intellectualism are of necessity committed to it as though it were a positive creed or a kind of principle. In fact, anti-intellectualism is usually the incidental consequence of some other intention, often some justifiable intention. Hardly anyone believes himself to be against thought and culture. Men do not rise in the morning, grin at themselves in their mirrors, and say: “Ah, today I shall torment an intellectual and strangle an idea!”

I find the passage striking for two reasons. First, because in light of such bumper-sticker slogans as make liberals cry again and how ’bout i put my carbon footprint up your liberal ass?, it would seem that some people do rise in the morning with the intention of tormenting their thoughtful neighbors and strangling any number of ideas, not a few of which are subsumed under the political philosophy with the carbon footprint up its rectum. It would also seem—and this is the second reason the passage hit me so hard—that the liberal idea typified by Hofstadter’s generous disclaimer, his implied insistence that most people are better than they seem, has indeed been strangled, or at the very least, is gasping for air. Who talks that way today?

And therein lies the rub. More than the parade of people walking into lampposts while gawking at their phones; more than the insatiable appetite for any kind of technologically enhanced spectacle, to the extent that political conventions, big-ticket sporting events, and megachurch services are virtually indistinguishable from one another or from a Nuremberg rally in their obsessive reaching for the unreal; more than the open disdain for science; more than the oxymoronic statement “I believe in science”—I know of no more definitive expression of stupidity than proudly professing a total inability to understand an opponent’s position on a controversial issue. That a fetus is an integral part of a woman’s body and thus under her sovereign moral control, that a fetus is a form of human life entitled to certain protections, that in a world where maniacs go around shooting schoolchildren it’s a good idea to get rid of guns, that in a world where maniacs go around shooting schoolchildren it’s a good idea to get a gun—“I simply can’t understand how anyone can think like that.” Really? Can’t agree with it, sure. Can’t accept its basic premises, fine. But can’t understand it? And yet I catch myself saying this all the time, and what is more, I think I might be telling the truth. Because after a while the refusal to understand becomes the inability to understand. Chronic stupidity is not the result of injury or genetics; it’s a learned behavior. We acquire it like a microwave or a suntan. What Dr. Johnson said of an acquaintance is a shoe that fits a whole marching multitude of feet:

Sherry is dull, naturally dull; but it must have taken him a great deal of pains to become what we now see him. Such an excess of stupidity, Sir, is not in Nature.

So what prompts people to embrace stupidity and cling to it even if it kills them—might we at least be able to understand that? Anyone who believes in popular government had better try. A natural ally of all authoritarian regimes, stupidity threatens progressive democracy in two ways: first by impeding its initiatives, second and more fatally by undermining any faith that those initiatives are possible or worth the effort. What good is “power to the people” if the people are dolts?

It’s possible that some individuals embrace stupidity because they’re afraid of being alone. Idiocy loves company more than misery does. When I taught school, I often remarked on the touching inclusiveness of the druggie segment of the student population. Looks, grades, and athletic prowess were of no account; the only requirement was that you do dope. There is an even more welcoming social circle where the only requirement is that you be a dope. Who among us hasn’t basked for an hour or two in the self-congratulatory stupor of the like-minded? In contrast, thoughtfulness can be a lonely choice, especially when accompanied by courage. (Nietzsche contra Twitter: “You seek followers? Seek zeroes!”) If COVID-19 has highlighted anything as much as some people’s feckless disregard for scientific evidence and the health of their neighbors, it’s the utter and often poignant inability of many people to endure solitude—or even, in some cases, to avoid a large crowd. If they can’t be in a packed bar, gym, or banquet hall, they’d just as soon be dead.

Writing several years before he would be executed for his progressively isolating role in a plot to overthrow Hitler, Bonhoeffer says,

We note . . . that people who have isolated themselves from others or who live in solitude manifest this defect less frequently than individuals or groups of people inclined or condemned to sociability. And so it would seem that stupidity is perhaps less a psychological than a sociological problem.

He goes on to say that although a stupid person is usually stubborn, his stubbornness shouldn’t be mistaken for independence. “In conversation with him, one virtually feels that one is dealing not at all with him as a person, but with slogans, catchwords, and the like that have taken possession of him.”

In short, one is dealing with extreme forms of groupthink. What James Baldwin said about liars, that they “travel in packs,” might also apply to the stupid, especially if stupidity is seen as a matter of lying to oneself. Liars “need each other,” Baldwin says,

for the well-being, the health, the perpetuation of their lie. . . . That is why all liarsare cruel and filthy-minded—one’s merely got to listen to their dirty jokes, to what they think is funny, which is also what they think is real.

But a confederacy of dunces offers more than social acceptance through a shared denial of reality. What the stupid crave above all else is to transcend reality. To get above and beyond it. To feel all four tires leave the ground as one’s turbocharged chariot hurtles over the canyon in a Blu-ray apotheosis of brainless splendor. Reality, after all, is nothing if not constraining. Time, space, laws, facts, rocks, relatives, debts, and taxes all conspire to thwart the will and worry the mind. Auden dubbed the middle years of the twentieth century the Age of Anxiety; in the Age of Stupidity, anxiety takes a hike. The burdens of the past (e.g., slavery and Jim Crow) and the dangers of the future (e.g., environmental catastrophe) are transcended in a grotesque parody of “living in the moment,” grotesque because time inevitably reasserts itself in the form of sentimental history and puerile futurism. In the glorious past, real (that is, white) Americans doled out liberty and justice from the sanctified barrel of a gun; in the glorious future, robots and genetic engineers will save us from the indignity of brushing our teeth. Whether on horseback or in a hovercraft, a fool’s feet never touch the ground. He is borne aloft, like a maharaja or an infant.

Those who study stupidity as a psychological phenomenon have noted that conspicuously stupid acts often result from what Robert J. Sternberg calls “feelings of omniscience, omnipotence, and invulnerability.” No doubt traveling in a pack can supply the necessary lift, but some people manage it quite nicely on their own. The state in which I live is home to one of the more docile species of bears on the continent, yet in the past decade black bears have attacked at least two women who persisted, in spite of neighbors’ complaints and game wardens’ warnings, in feeding the bears from their porches. Then there was the fellow in Florida who was bitten while attempting to kiss a rattlesnake. Human and animal, tame and wild, crazy and sane—these people are above such trivial distinctions, no small thanks to the civilization they have also fancied transcending. A Paleolithic ancestor who attempted to feed a bear or kiss a venomous reptile would have cut short his contributions to the gene pool; a postmodern contemporary who does the same things can count on being medevaced to the nearest facility that will accept his heath-insurance card. Book deal to follow. As a rule, liberals love Darwin, but as a matter of social policy they generally caucus on the anti-evolution side. One of the ironies of stupidity in its conservative and libertarian forms is its dogged opposition to the very safety net that stands between an imbecile and the harsher effects of natural selection. “Without all this government interference, I’d be free!” My friend, what you’d be is food.

Perhaps the best current example of stupidity as a bid for transcendence is QAnon, which according to the journalist Farhad Manjoo “has elements of a support group, a political party, a lifestyle brand, a collective delusion, a religion, a cult, a huge multiplayer game and an extremist network.” To subscribe to QAnon is to rise above reality-based politics and its complications. No need to fiddle with numbers or be frustrated by nuance. No need, in the course of a rational argument, to give some figurative devil his due. You’re doing battle with the devil himself, with him and his pedophilic minions, and no authority on earth can call you to account. You answer only to Jesus Christ and Donald Trump, secure in the knowledge that they can never disagree or even, in the latter case, be voted out of office in a fair election. Lately one hears any number of justified complaints about “losing our democracy,” though what some of the complainants fail to emphasize is the degree to which democracy is about losing: election after election, verdict after verdict, gain after gain. Loss is what adherents of an outfit like QAnon hope to transcend. They long for the ultimate victory, the final score, the metamorphosis from chumps to Trumps, to winners who can never lose.

I decided I ought to learn more about transcendence by borrowing several books on the subject from the library. The books were dense, abstract, and a bit dull. After only a few hours I wanted to transcend them. I hadn’t learned much for my essay, but I’d found another illustration of its central thesis. I’d located another instance of the need to “rise above” whatever one finds too daunting to bear. Do you remember that overwhelming sense in your first days of college—if you went to college and if the college you went to was worthy of your attendance—that all your professors and many of your classmates were so much smarter than you? To be willingly humbled by one’s own ignorance is not for the fainthearted, is not in fact for most of us, which may be part of what T. S. Eliot meant when he said that “human kind / Cannot bear very much reality.” Becoming sophomoric is a time-honored cure for the embarrassment of feeling like a freshman. One opts for stupidity in the hope of never having to feel stupid again.

It’s possible that our perception of stupidity varies in relation to the power of the perceived dimwit. When power becomes disproportionate to a creature’s level of intelligence or its sphere of reasonable entitlement, that creature starts to look stupid. A chicken doesn’t look stupid pecking around a barnyard but would look—and in effect become—terrifyingly stupid pecking at the controls of a nuclear power plant. Donald Trump would probably not have seemed all that stupid if his “very, very large brain” had been devoted to running a very, very small ice cream stand. In a society where the most ordinary of mortals is able to fly over continents with the insouciance of a god, operate an SUV the size of a mausoleum, address his inchoate musings to an audience of ten thousand followers, and wield a weapon with the firepower of the Alamo, the potential for looking and actually being stupid is enormous—even as that same lavishly equipped mortal lacks any guarantee that his duly certified ballot won’t be thrown into limbo by an online hoax or a presidential lie.

Which is the other side of stupidity’s disproportion: when someone’s power is less than what her intelligence or civic status would merit. I was surprised and then not surprised to discover that one of my dictionary’s definitions of stupid is “worthless.” We might with justice pause for a moment’s self-pity, positioned as we are in a society that sets us up to be stupid, that apportions us the technical power of wizards and the political power of dandelion fluff. Or if we imagine ourselves above self-pity, we might at least pity those who seek to transcend an enforced stupidity by embracing it. Oppressed groups have been known to make a tactic out of adopting the names and stereotypes by which they’ve been denigrated, so that, for example, a certain feminist cachet can attach itself to a woman who calls herself a bitch, a slut, a dyke, and so on. Call me a name, and I’ll shut you up by owning it. Treat me like I’m stupid, and I’ll show you stupidity like you wouldn’t believe. Any thought for my self-interest becomes the sacrifice I make to restore my self-respect.

More than one author has averred that it is impossible to fight stupidity. The contemporary philosopher Avital Ronell writes of the “temptation . . . to wage war on stupidity as if it were a vanquishable object.” She quotes Flaubert: “Stupidity is something unshakable. Nothing attacks it without breaking itself against it”—a cautionary note to those who would wage war on the MAGA mindset. Bonhoeffer is perhaps the most helpful here when he writes that “only an act of liberation, not instruction, can overcome stupidity.” He adds that “in most cases a genuine internal liberation becomes possible only when external liberation has preceded it.” Many people, including most religious people, would reverse the sequence, but here is one of the religious heroes of the past century putting external liberation first.

That is hardly consoling. Is it even possible to liberate a society so that an individual’s power exists in some meaningful proportion to her intelligence and entitlements, and in proper balance with the power of other persons and the finite resources of the planet? The activist Peter Maurin envisioned a society in which “it is easier for people to be good”; dare we hope for a society in which it would be harder for them to be dumb? Marshall McLuhan spoke of a society in which human beings become “the sex organs of the machine world”; dare I admit my preference for a society that doesn’t destine me to be a dickhead?

I need to be careful here. I imposed two strictures on myself when I began this essay: I couldn’t say that capitalism is making us stupid, and I couldn’t say that digital addiction is making us stupid, if only because it would sound pretty stupid to imply that in our present context there’s any clear distinction between the two. (Few things can take the strength from my knees like a liberation movement with a Facebook page.) Still, I can’t help quoting Bernard Stiegler’s self-evident observation that “in the Western industrial world . . . democracy has given way—and has done for quite some time—to consumerism,” which is “based on the liquidation of maturity . . . or in other words: based on the reign of stupidity, and of what so often accompanies it, namely cowardice and viciousness.” Like, for instance, trolling election officials with the aid of a “smart” device and threatening from the safe anonymity of cyberspace to rape their mothers. There is compelling evidence to suggest that our better emotions result from neural processes that the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio characterizes as “inherently slow” (how ironic that we use “slow” as a synonym for “stupid”) and that our empathy decreases the more distracted we become. In light of such findings, might we bring our supposedly scientific minds to question the wisdom of abandoning our politics to modes of communicative distraction that, like pre-political life as described by Thomas Hobbes, tend to be nasty, brutish, and short?

If we accept that stupidity comes from a loss of reality, and if we acknowledge that reality asserts itself most reliably through that creative interplay of mind and matter called work, then might one step toward our liberation from collective stupidity be a militant insistence on full, remunerative, and purposeful employment, the lack of which accounts for much of the simmering grievance that demagogues like Trump feed on? (If we could see the complete work histories of half the sad-sack insurrectionists who stormed the Capitol last Epiphany, we’d have a more illuminating epiphany than most of us deserve.) Marx located the origins of modern stupidity in a system of production that alienated workers from their tools and turned them into tools themselves. Is it possible to return the tools to their hands and to their rightful possession? The deniers of reality are always the first to call such a project “entirely unrealistic”—and perhaps it is, if only because their numb certainty makes it so.

If we cannot fight stupidity or its causes, we can at least try not to be stupid ourselves. We can reject the cant that passes for conviction and the cynicism that stupid people believe makes them wise. Trocmé did not tune his actions to the stupidity of Vichy policemen. He is said to have exhorted his congregation to make “little moves” against destructiveness—this from someone who saw stupidity as a prime mover in human affairs yet still managed the “little move” of joining with his neighbors to rescue thousands of Jews, most of them children, from the Nazis. The opposite of stupidity is not intelligence, much less knowledge or information. The opposite of stupidity is faith. Not necessarily religious faith, which in the common parlance of “belief” is not even faith in the ancient Hebraic sense. In Hebrew, faith (emunah) is something you live, often against stupefying odds. At first glance, faith might look like stupidity, because it too seeks a kind of transcendence, but through engaging with reality rather than denying it. “If I wish to preserve myself in faith,” Kierkegaard writes,

I must constantly be intent upon holding fast the objective uncertainty, so as to remain out upon the deep, over seventy thousand fathoms of water, still preserving my faith.

Objective uncertainty: How about the likelihood that the curse of white supremacy will ever be lifted from our land? Yet in the months following the murder of George Floyd, people of conscience, black and white, believers and nonbelievers, took their stand above seventy thousand fathoms of hatred and stupidity in order to enact their faith. Many of the protesters were young and, being young, bound to do a thing or two that an older person might call ill-advised. But stupid they could never be.