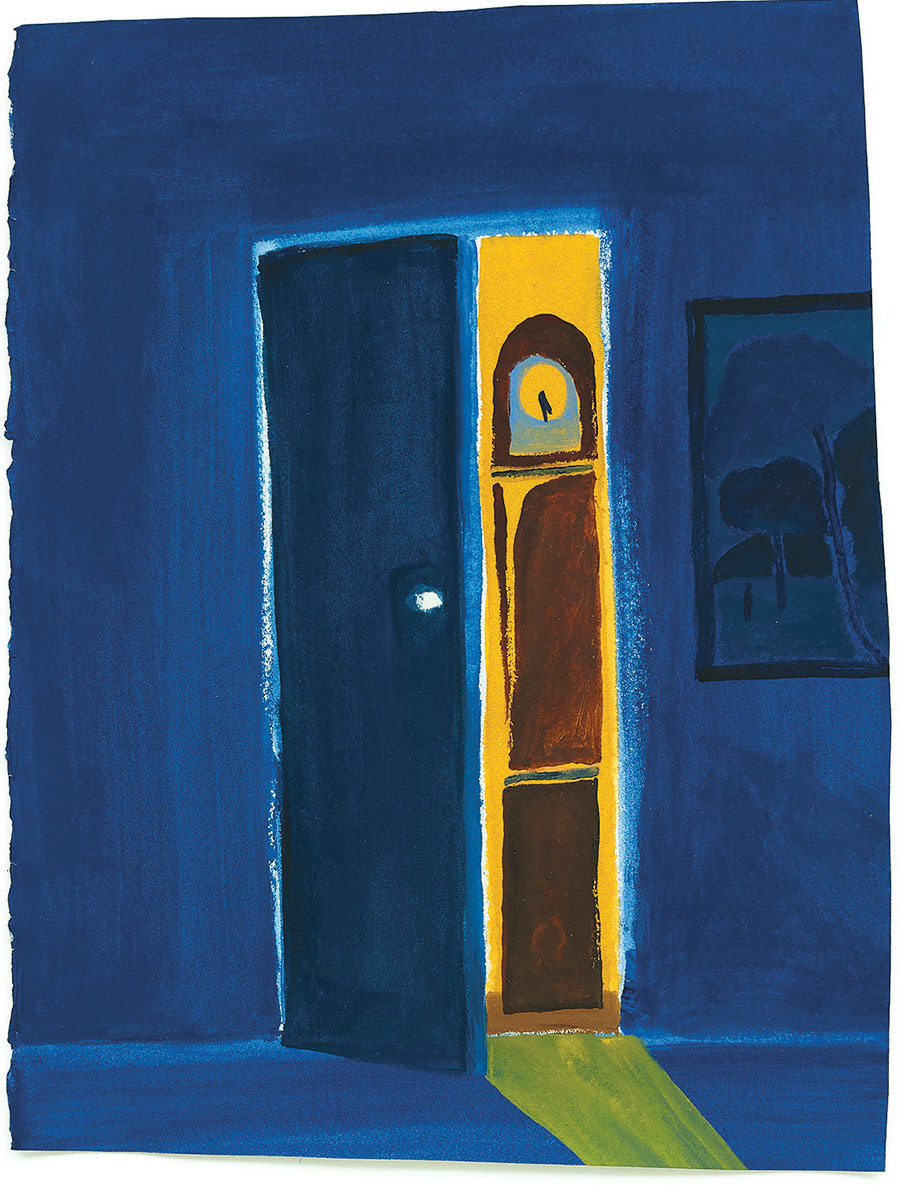

Untitled, by Matthew Wong, whose work is on view through April at the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto. All artwork © 2021 Matthew Wong Foundation/Artists Rights Society, New York City

Late at Night

Long after his fiancée had fallen asleep in bed, Adam Edwards read next to her on his phone. He thumbed the screen to scroll through a long article. The words glowed and passed. At the end, he removed his thumb. “Wow,” he thought to himself. He lay in the quiet night, in his soft bed, having just read the long, stimulating, very stimulating, article. A car cruised by on the street outside at slow speed. Shifting his focus away from the article, across the phone’s top edge, he settled his gaze onto the shadowy ceiling. The eye movement and the angle of his neck loosened his thoughts. “Wow, wow, wow,” he thought. He scrolled upward on his phone to look at the title of the article: “Maoism.”

The Wikipedia page on Maoism contained phrases he had never heard before, words he had not once been exposed to in his thirty-five years of American life. A question of tone had led Adam to the Maoism Wikipedia page. The tone of a line in a review of a video game, a game that Adam thought he might want to play someday. The author had mentioned Maoism, and the mention, in passing, sounded snarky to Adam’s ear, but without knowing anything about Maoism, he couldn’t really know how snarky, or whether it was, in fact, snarky at all. “I’ve heard of Maoism, of course, but I can’t say what it is,” Adam admitted to himself, wondering about the Maoism, and the snark. The mention in the video game review went like this: “You can even play as Maoists and buck history racking up buttloads of extra grain.”

What should he make of this? Adam needed to know, even though it was late at night, and his fiancée, Samantha, was asleep next to him in bed. It took forty minutes to read the entire Wikipedia page. And once he had, his previous ignorance of Maoism seemed impossible, since, as the article explained, and Adam accepted into his heart, Maoism was one of the most important political happenings in all of the twentieth century, the century into which Adam had been born. “Why hadn’t anyone told me?” he wondered fretfully.

In his mind’s eye, as if flipping through a slideshow, Adam tried to think of all the people he had known in his thirty-five years of life in America, none of whom had explained Maoism to him. His immediate family appeared first. They stood against the back of the house, its vinyl siding the color of raw chicken, hands on each others’ shoulders: Dad in his dress shirt for work; Mom in her favorite yellow blouse, most often worn to summer family gatherings; his sister much younger, for some reason, from a different era than the other two, a teenager in her volleyball uniform. They looked happy, genuinely happy, and already, looking at them in his mind’s eye, Adam wasn’t so surprised that these people had never talked about Maoism.

He pictured other people he had known, teachers and uncles and classmates, but soon he stopped. It would’ve been far too difficult for Adam to cycle through everyone he had ever known, even under such relaxed yet stimulating circumstances. Born in a large town, he had graduated from a large college in another large town, and now he was employed in a third large town at an important and growing institution; he had known literally thousands of people in his life so far. The three towns—the birth town, the college town, and the growing-institution town—formed a triangle with an area of nearly 490 square miles.

But for Adam, the small sample he had seen in his mental slideshow offered a clue: maybe no one in this whole group, this sea of thousands, even if many of them had heard of Maoism, knew enough about Maoism to talk about it. How could any of them have approached Adam, said “Maoism,” and then continued from that word?

“I could tell them about Maoism.” Adam’s eyes had adjusted to the dark. Now parts of the room looked merely dusklike. He could become a teacher of Maoism, or, at least, a Maoism explainer. Suddenly, it seemed oddly necessary to know everything about Maoism, and the need to know seized him fervently. He began the Wikipedia article again, from the top:

Maoism, or Mao Zedong Thought (Chinese: 东思想; pinyin: Máo Zédōng sīxiǎng), is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed for realising a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People’s Republic of China. The philosophical difference between Maoism and Marxism–Leninism is that the peasantry are the revolutionary vanguard in pre-industrial societies rather than the proletariat.

“Vanguard.” An icy shiver passed through Adam: thirty-five years old, learning about vanguards for the first time. Under the sheets he moved his feet and clicked his ankles in an attempt to fidget away from the discomfort of his ignorance. “Proletariat. I know what that means,” he thought. “Or maybe I only kind of know what it means. Poor people.” He thought about members of his mother’s extended family, who were poor and possibly proletariat.

Daybreak Blue, by Matthew Wong

Restlessness surged through him. He wanted to jump out of bed, but that would have woken Samantha. Samantha found his enthusiasm infectious, but something told him: not this time. She, like he, had to work in the morning. It was hard enough to wake refreshed when you hated your job, without late-night discussions of Maoism. It all depended on the principal. This school, the one Samantha was currently working with, had a bad one. When entering into a school and demonstrating that standardized test preparation can be done in such a way as to allay apprehension, minimize self-doubt, and foster mindfulness, things can go very well or very poorly. A school’s culture emanates from the principal. Schools are strangely local in that sense, even those in large cities or under the umbrella of much larger entities, and Samantha would go as far as to say, when she really got going on the subject, which was often, that it didn’t even matter for how long the principal had been there. From day one under a new principal that school was different. There’s something obliterating about the personality and acumen of a new principal, Samantha said, no matter the specifics of the personality or the acumen.

It would have been wrong to wake Samantha and make her peer into the night’s darkness. She was a light sleeper. When he jumped out of bed, she would hear the thump of his heels on the floor, put her glasses on her face, and see her fiancé’s dim outline standing at the bedside. She would do all of this just to hear him say, “Oh, sorry. I’m just getting really excited about Maoism, which I know nothing about. You?”

But he had to get out of bed! Carefully, he slid his feet from under the covers until the bare air touched them. Soon he was standing upright, and he took the water glass from his bedside table. In his other hand his phone glowed against his white Hanes boxer briefs and V-necked T-shirt. He eyed the closed bedroom door a few paces away. He liked closing the door to the bedroom before they went to bed. It finalized the night. Slowly, Adam moved toward the doorknob. He reached for it and twisted his wrist with dramatic deliberation to keep the latch from clicking. The hallway outside was much darker than the bedroom. He closed the door behind him with a thin creak. No sound from the other side. He grinned.

“Maoism, Maoism.” He tried to erase his smile.

The narrow hallway led to the living room. He made out the shapes of the couch, the television, and the bookshelves, which were crowded with DVDs, books, video games, board games, and collectible toys. He walked to the kitchen and, without turning on a light, filled his glass with water. The time on his phone read 12:46 am. In less than seven hours, he would walk back into the kitchen to start his morning. Adam was the assistant director of systems operations for a local museum. It was a museum dedicated to preserving the history of the early settlers of northern Illinois. Thirty buildings, restored to their nineteenth- and early twentieth-century conditions, many moved by heavy construction equipment from the surrounding area so that they could be experienced all together, as a city of sorts, in Naperville, a suburb of Chicago.

He had always loved solving technological problems. Colleagues often sent him their problems via email. Now, at the sink, he checked his email. Several messages described work that he would complete when he arrived at the office at 8:30 am that morning. For instance, the museum had implemented some recent cloud initiatives, and now the vice president of external affairs could not access the cloud for pictures from a fundraiser. “Need these. Can you look up my password?” Yes, Adam could look up his password.

None of the problems described in his email reminded him of the problems he had imagined when he first tried to learn about computers, as a teenager. The 1990s: the internet was heating up; computer games were exploding in complexity. Adam’s father had to learn about computers, too, for his work. “Using them more and more,” he would say. “Everything’s getting computerized now—it’s interesting!” As he looked over Adam’s shoulder while Adam played a game on the computer, which was located in the corner of the living room: “Very interesting what these new computers can do.” Then he’d leave and turn on the TV in the family room.

One day, the older man checked out a book on C++ from the library and gave it to his son. “I can’t make heads or tails of this,” he said casually as Adam finished lunch, a bowl of Frosted Flakes, at the table. “Can you?” Adam humored his dad and opened the book in front of him. Chapter 1: Introduction to Computing. After an introductory paragraph, which Adam did not read, he saw:

Algorithm 1.1

The Babylonian Algorithm for Computing the Square Root of 2

This is the algorithm that the ancient Babylonians used to compute the square root of two (√2):

1. Set y = 1.0.

2. Replace y with the average of y and 2/y.

3. Repeat Step 2 until its effect upon y is insignificant.

4. Return y.

He didn’t want to admit his confusion to his father. Instead, he sneered, “Why did you get me this?” His father looked hurt. He hadn’t steeled himself for such a reaction. “I just thought, you know, something new to figure out.” He zipped up his windbreaker and disappeared outside. Maybe to mow the lawn?

But all afternoon the algorithm flitted across Adam’s mind. As he played outdoors, and as he played indoors. He had never seen the word “algorithm” before, so he remembered it as a blank spot next to the word “Babylonian.” Outdoors and indoors, he thought, “Babylonian ______.” As he played H-O-R-S-E with Drew: “Babylonian ______.” As he played Civilization II: “Babylonian _______.” So later, when he went into his room, and he saw the C++ book on his desk (his father must have put it there), Adam picked it up again. He wanted to see the bewildering word. Seeing “algorithm” again, and locking its tightly compressed four syllables into his mind, he also saw, free from the gaze of his father, that beneath the algorithm those four steps which had so surprised him with their utter alienness were actually quite understandable using his knowledge of variables from algebra class. What had loitered diffusely in his mind all afternoon was now a sharp and satisfying set of steps. His pride swelled, and an unusual feeling of certainty mingled with the pride. “Someday I will master this,” he thought, looking at the book. “Just a normal kid, mastering the Babylonian Algorithm and C++. That’s who I am.”

In the kitchen of his and Samantha’s apartment, Adam refilled his glass of water. Small emerald reflections swirled through the glass’s curve from the light of his phone. He didn’t really know anything about politics. It was, to use the word again, bewildering. He knew who the president was. And he knew why people were protesting. He had even thought about protesting, but he always had other plans. Or Samantha had plans, and he was part of them. Plus: there was no difference between 4,000 and 4,001 people at a protest. That was a mathematical fact he could never get around. Sure, someone might say, “But that 4,001st person, they might do X,” X being some galvanizing thing. But galvanizing others at a protest didn’t seem like the kind of thing Adam could do. “I don’t know enough about politics to do X,” Adam would say. The person who encouraged him to be the 4,001st person would have to agree.

Adam hurriedly read more about Maoism, which is to say that he skimmed the Wikipedia article again. Under the headline “Differences from Marxism” he read:

Mao based his revolution upon the peasants, because they possessed two qualities: (i) they were poor, and (ii) they were a political blank slate; in Mao’s words, “A clean sheet of paper has no blotches, and so the newest and most beautiful words can be written on it”.[23]

“A blank slate. That’s what I am,” Adam thought to himself. He left the water glass on the dark bottom of the sink and ambled to the living room. He turned on a lamp and paced slowly in front of the bookshelves. Adam liked to walk when he had to think about a problem. This was considered unusual for a man who worked with computers. He was expected, he thought, to like sitting in front of a computer. And he did like it. Sometimes, though, when there was a complicated problem to solve, midway through the solving process, not always when he was stuck, but sometimes when he was, he would tell his boss, the director of systems operations, that he was going to take a short walk. He’d simply pop into her office next door and tell her so, adding, “But I’ll have my phone on me.” His boss hadn’t indicated that he was doing anything unusual by taking walks during the workday. But she didn’t tend to indicate things like that. He once saw her eat half a sandwich and then say “I think the ham went bad” without changing her expression. She just threw the rest of the sandwich away.

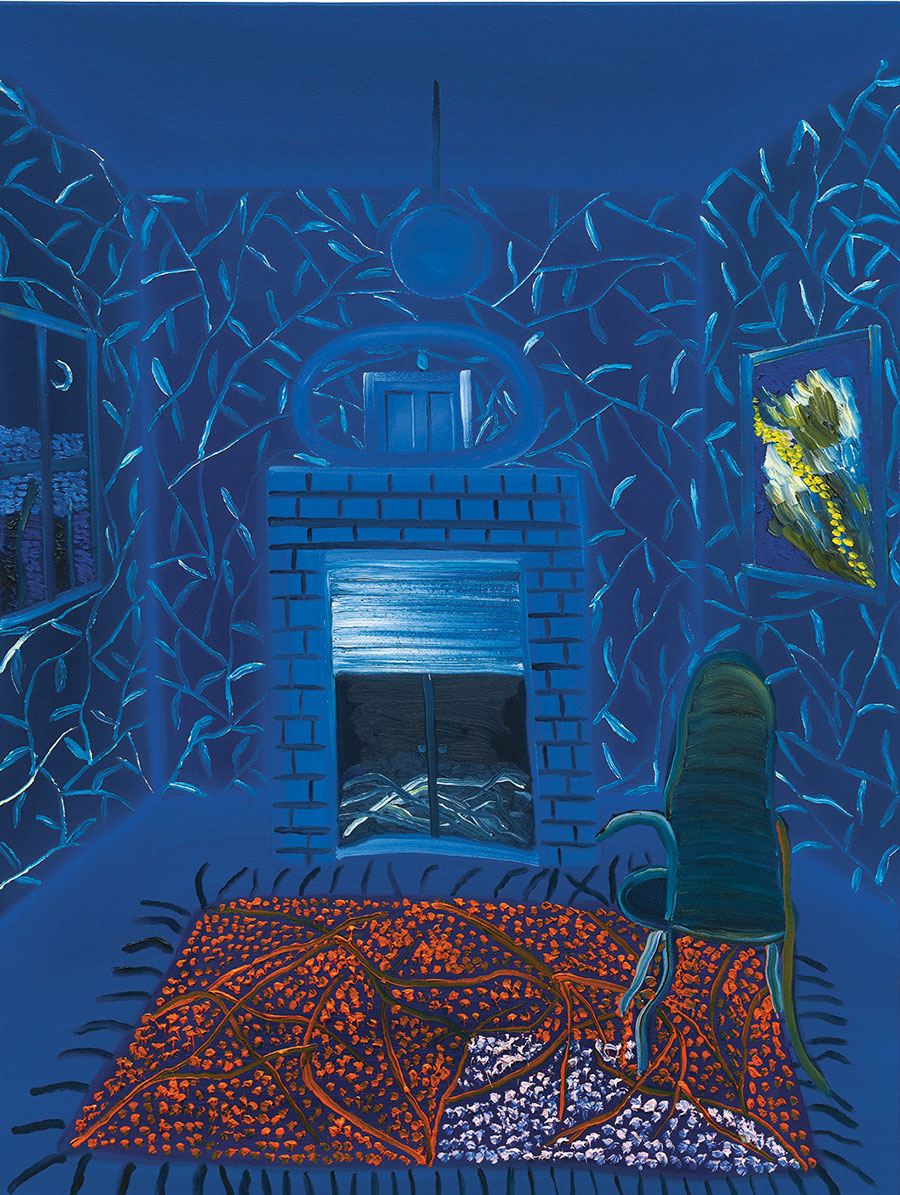

Fireplace, by Matthew Wong

A picture in the Wikipedia article, of Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon shaking hands, appeared in Adam’s mind. Both men seemed pleased, but a lot had happened since then. A lot that Adam knew nothing about! Each time Adam paced toward the window, the image of Maoism assembling inside his head projected onto the glass. “Differences from Marxism,” he thought, onto the window. The wood floor creaked in different places each time he crossed the room, and Adam was always glad when his pacing brought him, for a few steps, onto the rug. (“What if I had a pacing rug? The length and size of my pacing?” he thought.) He stopped and looked at the bookshelf. “Nothing on here about Maoism.” Suddenly, the bookshelf disgusted him. He looked at his Star Wars toys. Obscure Star Wars characters. Obscure aliens, obscure humans. What a full, varied universe. And some of the common Star Wars characters, too, like Chewbacca, the Wookiee, standing there, saying, “Hi, Adam.” “I love these characters, and yet, right now, I hate them,” Adam thought. He pictured little Maoist toys instead. What did these Maoist toys look like? Chinese men and women wearing red and gray. Adam’s life seemed more interesting, larger, with these Maoist toys on his bookshelf. The Maoist toys, sitting on his shelf, even next to the same books, DVDs, video games, and board games, signaled a seriousness that Adam was fast realizing he did not possess. Yes, the Maoist toys deepened his life. They were mysterious, figures of a different time, a time to which Adam was not expected to have a relationship, but here he was, celebrating this time and its seriousness in toy form. The Shaanxi province, with its prefecture-level city of Yan’an, as it were, materialized behind the rows of figurines. He pictured it as best he could, and Yan’an looked like a desert city of intrigue and grandeur, one he would like to visit and explore, but from behind Yan’an, the face of Chewbacca kept penetrating. Soon Adam couldn’t see Yan’an at all. The Maoist toys disappeared, too. Only the Star Wars toys remained.

He paced again. And every time he tried to think about Maoism, really think about it, he hit a dead end. He didn’t know enough about Chinese history, twentieth-century history, or political categories to be able to think as deeply as he desired to think. Every time he retreated from thinking about Chinese history because he didn’t know enough, he ran straight into the wall of twentieth-century history, about which he was similarly mystified. Without being able to see any of the three overarching topics clearly, Chinese history, twentieth-century history, and political categories, he kept coming back to one question: “What would it mean to believe in Maoism?”

It was then that, thumbing through the article, he accidentally thumbed past the last section on “Mao-Spontex,” beyond the seventy-five footnotes, and saw “Further reading” for the first time. He felt as if someone had flung him a life preserver. Of course: he could read a book about all of this. “They have whole books on Maoism,” he chided himself. Calmly, he scanned the list. Eighteen bullet points delineated fourteen books and four scholarly articles. Which book was the correct choice for a beginner such as himself, someone who needed basic concepts defined, but who also desired mastery, total comprehension?

He eliminated the four articles. They all compared Maoism with something else, and he wasn’t there yet. Serenely, he saw another way to winnow: many of the books focused on areas adjacent to the core principles of Maoism and said so right in their titles (Maoism at the Grassroots: Everyday Life in China’s Era of High Socialism, for instance). Eventually, he would need to know about these adjacent concepts, but first he needed to study the basics. He was now down to three titles.

“I’ll buy all three,” he thought. He sat down on the couch and reached toward the coffee table for his laptop.

He opened it and searched for each book on Amazon. Mao’s China and After looked like everything he could ever want, plus it was available on Prime. He added it to his cart. The Political Thought of Mao Tse-Tung was unavailable except at exorbitant prices, or secondhand, which would mean no free shipping. Adam balked. He did not add the book to his cart. Mao Tse-Tung, The Marxist Lord of Misrule: On Practice and Contradiction promised something fun, like a treat, but copy-and-pasting that title into the search bar brought back differing editions of the graphic novel adaptation of the Percy Jackson book series and an array of strange Lord of the Rings products, like a decorative towel. Adam sighed. “I guess it wasn’t meant to be.” So that left Mao’s China and After and nothing else. Perhaps it was better to start with one book anyway. He chose to have it shipped to his office. It would arrive by Friday afternoon. The menu bar running across the top of the screen said 1:58 am. He opened the Maoism Wikipedia page again on his computer. The bigger screen revealed previously unseen aspects of the article. Here was something he had missed:

In the late 1970s, the Peruvian communist party Shining Path developed and synthesized Maoism into Marxism–Leninism–Maoism, a contemporary variety of Marxism–Leninism that is a supposed higher level of Marxism–Leninism that can be applied universally.[7]

He could see himself reciting the above paragraph, onstage, as if the words were his own, and he felt the electricity of the words as he soberly whispered to himself: “Shining Path . . . ” “A supposed higher level . . . ” Adam wanted to be attached to ideas that required saying such words with a straight face to others who also took them seriously. He had a history of doing this. He had been part of a rock band in college, and he had been raised Roman Catholic. It was a pleasure to talk to your bandmates and to fellow Roman Catholics in this serious way, and to be taken seriously. He wasn’t in a rock band now, and he didn’t attend church, so when he did tell new friends that he had been in the Fiery Trial, or that he had been confirmed in the Roman Catholic Church, he had to do so with a bit of irony. Because he didn’t believe in either of those things anymore. It was as simple as that. He had lost his faith, and the Fiery Trial never attracted much enthusiasm, even in their bustling college town, where they once opened for O.A.R., whose bassist, Benj Gershman, said that he thought they had been “locked in.” Adam had been part of so many things in his life, and he was part of many now. He and Samantha rented this apartment together, for instance, with no one else.

He was not Roman Catholic because he had lost his faith one day at the age of sixteen. This was not uncommon. There had been no one in the church who could talk to him about the questions he was having about right and wrong. These questions involved sex, mostly, and horrible wishes. He couldn’t go to Father Ernie: Father Ernie didn’t look like a priest. He looked like a bit player in a workplace sitcom. There was no way to trust Father Ernie with knowledge of his horrible wishes.

“What about a documentary?” Adam thought to himself as he sat in the living room.

He went to YouTube and searched “maoism documentary.” In the results he saw thumbnail after thumbnail of Mao’s face, actual and animated. “To think,” Adam thought, “I’ve seen his face so many times before, not quite knowing who he was, but now I recognize Mao Zedong easily.” The first result differed from the rest. It did not contain Mao’s face. “China: A Century of Revolution 1946–1976” featured an image of a Chinese man with a young child clutching his shoulders from behind. The camera zoomed in on their faces in the short, looping preview that played when Adam hovered his cursor over the thumbnail. The video had been uploaded by someone named Richard Hogan. It was movie-length. Adam clicked.

The opening sequence suggested that this was a serious full-length documentary that had run on American TV near the end of the last century. Words appeared in gold: “The Mao Years.”

“Perfect,” Adam thought.

Soon enough, people who had lived through the Mao years in China talked about their experiences. Over old newsreel footage, Adam heard a narrator, the sort of serious man one expects to hear in a documentary of this kind: “They wanted to transform the lives of one quarter of mankind.” Okay, but what was Maoism? No one explained. Everyone spoke too slowly, too elliptically. The pauses between people talking seemed to go on for minutes, with B-roll footage of crowds and construction and music filling the silences. Adam tried to relax as a Chinese woman explained that because of Mao, women could marry the men they loved.

And as he sat back, the image of himself onstage reciting the Maoism Wikipedia page as if he himself had written it, because he knew all there was to know about Maoism, appeared in his mind’s eye again. “Shining Path . . . ” The image was pleasing, and imaginable, but then his thoughts focused on the crowd. Who was in the crowd? Those interested in Maoism? Maoists? Was, in this vision, Maoism experiencing an onrush of popularity, and so experts, ones like Adam, were being tapped to give high-profile public lectures on the nuts and bolts of this important yet undercovered political theory? Yes, Adam decided, people were interested in Maoism again. And he was in the right place at the right time. And so he walked onstage. “Shining Path . . . ”

Adam paced again in his living room, leaving the documentary to explain the Korean War in the background. Adam didn’t even know that China had anything to do with the Korean War. Yet nearly one million Chinese soldiers had been killed or injured! And Adam’s grandfather had been there, too. Well, not in Korea, but in the Pacific. He had never said anything about Maoism, either. And now he was dead, dead from working too hard building aboveground swimming pools. Adam’s eyes did not return to the screen. He checked his phone, to study the Wikipedia article again.

Hours passed in the semi-lit living room. The prospect of knowing about Maoism seemed within reach. China became closer, as did the twentieth century. Political categories sorted themselves. History: weaving. Change: profound. Turmoil: expected. By 4 am, Adam had mulled over much more of the Wikipedia article. His digestion process looked something like this: marveling at the existence of a new area of information, such as a whole section labeled “Contradiction,” and then, after some light daydreaming, picturing himself showing off knowledge of that section in real life.

For instance: the next night, like every Wednesday night, Adam and Samantha would gather in downtown Naperville with two other couples for bar trivia. The group chats idly, amiably, between rounds, drinking draft beer under blue light. Ben, Samantha’s friend from work, who is too tall for the stools, returns from delivering the team’s scorecard to the bar trivia emcee, and as Ben approaches the table he complains that he’s sure some of the answers he has just delivered are wrong. Some in the group turn their heads. “Well, I don’t really know they are wrong,” Ben concedes. He just has a feeling. Twice in the previous round, the music round, the table was unable to agree on a definitive answer, and twice the table arrived at a wary, vague consensus. Both times, Adam chose that moment to intervene with a new answer, one that nobody even mentioned in the previous throwing-out of possibilities. Adam then convinced the table to side with his new answer against the original vague consensus. He spoke passionately, enthusiastically, and the others became convinced. (At least, convinced enough.) But now Ben regrets Adam’s “coercions.” Adam forced the rest of the group into tying themselves to “long shot” answers. “They’re long shots!” Ben says, staring down Adam. Ben bangs his fist on the table, which wobbles. Others lurch for their drinks, to keep them from spilling. And Adam merely smiles as beer slips over the rim of his glass. Everyone wonders how he will respond. With all eyes on him, and Ben huffing and fuming, Adam lifts the glass, takes a slow sip, places the glass down, and says, “Coerced? Well, political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

That this scene did not make much sense indicated that Adam was finding it hard to come up with any situation from his everyday life in which he could realistically demonstrate his expertise in Maoism. For starters, the idea of Ben banging his fist on the table was all wrong. As Samantha often noted, disdainfully, Ben was a pushover. Plus, Adam and Ben got along great. And yet, the scene pleased Adam. Here he was, in a situation that had the texture of a situation in which he might find himself, talking to the people he knew best, saying the words of Mao Zedong. What better proof could there be that he was an expert?

His laptop died before the documentary finished. He heard the rumble of a distant motor outside. “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” he said, aloud, in the hush of the living room, loud enough for the Star Wars toys, but not Samantha, to hear. “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” he said again, as if coaxing the words out of hiding.

Adam had stayed up late reading the internet before, but not like this, not with such elation. He didn’t get out of bed when reading about Soylent, Alan Turing, or serial killers. Why this then? Why tonight?

Samantha and Adam were scheduled to marry the following Saturday, February 8. Their family members and friends would attend. Many, many family members and friends. Neither Samantha nor Adam had intended it that way, but that’s how it had turned out. Planning had gotten away from them. Luckily, marrying in the Chicagoland area in winter meant a discount on the venue. Other vendors had also given them a discount. So some things hadn’t gotten away from them. But then, for example, in October, an important relative of Samantha’s declared that he couldn’t attend the wedding on February 8. His potential absence caused a lot of hand-wringing, and Samantha spent hours on the phone with her mother, uncle, aunt, and the wedding planner trying to figure out a way to make it work. Once, over her shoulder, as she dialed Aunt Maggie for the third time that day, Adam said, jokingly, “Let’s just have another wedding for Uncle Albert.” Samantha laughed. About a week later, after much cajoling and family discussion, Uncle Albert found a way to attend on the eighth. It seemed pretty easy for him to do so in the end—he never gave a convincing reason for why he couldn’t attend on the eighth in the first place—but the Uncle Albert incident got Adam thinking: Why not get married many times?

The problem with the wedding, it seemed to him, was that it would happen just once. If he and Samantha married several times, the multiplicity of events would relieve the stress of planning a single, momentous occasion. He didn’t mention this idea to Samantha. To tell her, he would need reasons that sounded convincing. All he had was a feeling.

And then, one workday morning in early December, while walking from his car to the office, an unadorned nineteenth-century building, visible in the middle distance under a bright-gray sky, he hit upon the way the logistics of several weddings could work: a road trip, driving from location to location, marrying at each stop in front of a few attendees. The bride and groom would travel to the guests, instead of the guests traveling to them. A marriage tour! He could see it now: the tour would transform the act of marrying. Instead of all the time, money, thought, and energy concentrated onto one single event, an event that loomed so large that Adam and Samantha, as bride and groom, were merely bodies sucked into orbit around it, he and she could plan many smaller, charmingly low-stakes events that cohered into an exciting road trip through the Midwest. See part of the country, see the people they loved, have a lot of fun, and get married many times! They would need to postpone the wedding until late spring for better driving conditions, of course.

Adam saw Samantha’s face in front of him, and he felt tenderness. He had resigned to the fuss of the wedding, the fuss that would obscure the romance of the single event. The single wedding was to be held in a large Roman Catholic church in Samantha’s hometown. They had driven there twice, and Adam had taken in a lot of the details of this formal, ornate church while also wondering what it meant, as a lapsed Roman Catholic, to omit the lapse so that he could marry in the priest’s church, the same church he had never trusted with his horrible wishes. Adam had met with the priest, Father Jerry, twice, and Adam had talked on the phone with Father Jerry that same number of times. Father Jerry was an older man, but an older man in his prime. He looked and sounded like an excellent golfer. He was priestlike. He understood exactly how to talk to Adam and Samantha about Roman Catholicism, and becoming married Roman Catholics, without forcing either of them to outright lie about the level of their commitment to the Roman Catholic Church. Which was nil. Father Jerry must have understood it was nil. He wasn’t an idiot. He was in his prime. So it didn’t worry Adam too much, or Samantha either, for that matter. But what if this lie, this group self-deception, entered into Adam’s mind during the ceremony? The single wedding event would force him to look in the eyes of his two fellow deceivers quite often. What if, during that eye contact, he had a new qualm with this lie? How would he control his face? It wasn’t one of his strong suits.

With a shaggy, quirky, delightful road tour of small, intimate ceremonies, Adam need not worry about lying with a horrible look on his face during the wedding. He could live in the moment of marrying Samantha, a moment he knew he wanted to remember. He could look into her eyes, at her dress, he could feel the weather, there would be all sorts of weather, and both of them could say, one-hundred-percent thinking about the words, “I do.” And rather than have one shot, they could have many. Over time they could improve at marrying. They could have practice! In the car, between stops, they’d discuss strategy. Playfully. The tour would include ten stops, as Adam saw it, not counting opening and closing nights in Naperville: Glen Ellyn, Illinois; Beloit, Wisconsin; Rochester, Minnesota; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Olathe, Kansas; Evansville, Indiana; Indianapolis, Indiana; Lima, Ohio; Merrillville, Indiana; and West Lafayette, Indiana. This was romance. Romance and sentiment. “We would have a story to tell for the rest of our lives,” Adam thought, sitting in the living room. “Hardly anyone else has ever had a wedding like this.” To make sure about that, he had googled his idea and learned that in 2015 a couple had flown all over the world, marrying in as many countries as possible, and posting photos of themselves in each new exotic location on Instagram. His and Samantha’s weddings would be different. He liked to picture the final event back in Naperville. He and Samantha would drive the two and a half hours from West Lafayette to arrive at their Naperville apartment early in the afternoon. Blearily, they shower, eat takeout from Potter’s, and the weariness of the past weeks’ travel sloughs off them. They put on their wedding outfits—one last time! tonight!—and head to the childhood home of Janet, Samantha’s best friend, whose parents have offered their large backyard for the evening. Christmas lights run from tree to tree above the grass, and a PA system sits near a small stage laid on the lawn for dancing.

Late at night, after the chummy, loose ceremony—complete with jokes—and a buffet-style dinner, everyone waits near the small stage. They’re waiting for the reunion of the Fiery Trial. One by one, the members take the stage: Josh at his kit first, then Doug to tune his guitar, his head down in total concentration. He hasn’t changed one bit. Breanna and Tuck, now married, so Adam heard on Facebook, joking and laughing as if still in the early stages of dating. They pick up bass guitar and electric guitar (rhythm), respectively. “Testing, testing,” Tuck says into his microphone. Then the man in the tux, Adam, arrives at the keyboard. He plays some thick major chords. “Hello hello,” he says into his microphone. The crowd goes quiet. “We’re the Fiery Trial.” And before the applause can even start, they launch into their opening number, Marvin Gaye’s “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You).” They play it by the book, and yet it’s entirely their own. The crowd moves forward to dance.

“It’s too late to ask her about the road trip,” Adam thought, sitting on the couch in the living room. “If I brought it up now, it would only create problems.” The wedding was in ten days. He ran his hands over a stack of the board games that he and Samantha liked to play together. Suffice it to say, none of the games mentioned Maoism. “This will be a very important moment in my life, whether I like it or not.”

He walked back into the dark kitchen and opened the fridge door. He pulled out a jar of blue cheese–stuffed olives. “And I do like it. I don’t mean to be so dour,” he said to himself. He opened the jar, dug a fork out of the drawer, and scooped out two olives. “Everyone gets a little antsy before they get married. Tonight it’s my turn.”

He ate seven olives. Then he went for the leftover pad thai. He closed the refrigerator. “Becoming an expert in Maoism,” he thought as he ate the cold noodles, “would become a large part of my history, too, just like getting married.” It was the best pad thai in Naperville. “Even if I didn’t tell anyone, it would be a very large part of my history.”

Then, one day, he thought, on the day he died, someone would look to write his obituary, for Adam Edwards had been a solid citizen of the city of Naperville for several decades. He was not a pillar of the community, but one of the steps underneath the pillar. If he was picturing a building in Greece correctly, the steps held up the pillars. And when the obituary reporter went looking into Adam’s life, doing the gumshoe reporting that such a reporter does, she would be surprised at what she found. Arriving at the Edwards-Cunningham household, the reporter encounters a family gathered not in mourning but in active silence, the living room a mess of open boxes of books and notebooks. The widow flips through pages in total concentration. The daughter has placed a set of old hard drives on the coffee table, and one is connected to her tablet device. She’s scrolling through images. The son, who had opened the door for the obituary reporter, a humble smile on his face, returns to similar scrolling, bent in concentration. “What a remarkable scene,” the obituary reporter thinks. She makes a small note in her notebook: “Born again?”

“Can I have a look?” the obituary reporter asks.

“Of course,” Adam’s daughter replies. She hands the obituary reporter a copy of the will. “You might as well start here.” Hours later, still sifting through notebooks and talking to the family and all those who stopped by to pay their respects, many of whom, after receiving the latest news about Adam’s dedication to Maoism (“His what?”), stay to leaf through his papers, too, the obituary reporter dares to admit to herself that this was exactly the sort of affirming work she had hoped to find when she entered the field of journalism. Where else but in this field can one stumble into a home and find that a recently deceased, solid member of the community had been, in actuality, a passionate and virtuosic Maoist? (The obituary reporter already knows a little bit about Maoism, more than enough to recognize that a dedicated Maoist, secret or otherwise, wasn’t something you found in Naperville every day.) Soon the obituary reporter offers condolences again and, invigorated by the afternoon, excuses herself. She wishes she could stay, but there is a deadline to make. The finished obituary reads something like this:

Adam Edwards was a committed citizen of Naperville, Illinois, for forty-three years. Beloved son of Arnold and Nancy Edwards, dear brother of Jennifer Edwards, loving husband of Samantha Cunningham Edwards, loving father of Casey and Amanda, loving uncle of Stephen, Alexander, and Patricia, beloved son-in-law to Terry and Eleanor Cunningham. Edwards grew up in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, and attended Purdue University, where he studied computer science. Edwards was a kind, curious man, and he spent his career as an administrator overseeing computer systems in many important Naperville institutions, including the DuPage Children’s Museum, Edward Hospital, and Naper Settlement. Surprisingly, in his last will and testament, Edwards revealed himself to his family to be a “scholar of Maoism” and a “Maoist.” “The questions—and answers—of Mao Zedong have guided me throughout most of my life and, in fact, all of my married life,” he wrote. “It has been a privilege to navigate my life, even in this capitalistic, imperialist country, with the help of the wisdom of Mao Zedong and the variety of Marxism–Leninism that he introduced to the world.” He continued: “I leave for my children my collection of books and data on the subject of Maoism, and also my extensive commentaries. These can be found in a set of boxes in the attic. I especially hope that my writings on the subjects of dialectical materialism, left deviationism, and the tenets of Maoism embraced by Peru’s Shining Path are of great help and concern to you. It would be humbling if my work were to be found, in the famous phrase describing Mao’s legacy, ’70 percent right, 30 percent wrong.’ ” Those last words are taken from a quote by Deng Xiaoping, a successor to Mao Zedong. Edwards had requested that his work on Maoism be broadcast as widely as possible. “It’s too easy for something to be lost forever,” he said. “I almost never came across Maoism. No one told me about it. But then, one night, I did hear about it, and it changed my life forever.” Edwards’s daughter, Amanda, after learning about her father’s Maoism, said, “I feel like I’m meeting my father all over again. And I’m learning about Maoism.” Edwards’s wife, Samantha, said, “He was always dedicated to his family, his job, and his community, so it’s not that surprising to find that he was so dedicated to Maoism.”

The sun had not yet risen when Adam slipped back between the sheets without causing Samantha to stir. Was he tired? He lay on his back and looked up at the shadows. He would find out when he woke up in a couple of hours. “And I wonder if she’ll notice,” he thought. Not just whether he was tired. “I wonder if I’ll seem different tomorrow.” He corrected himself. “Different today.” In the darkness, he quickly fell asleep, though not before he pictured himself at the end of the workweek, when he would stay late at the office waiting for the book on Maoism to arrive. It’s true that the book would likely be delivered earlier in the day, but you never knew. And if all else failed, which was always possible, he would find the book in the office the following Monday. It could wait.