This is the new world that I read about at breakfast. This is the great age, make no mistake about it; the robot has been born somewhat appropriately along with the atom bomb, and the brain they say now is just another type of more complicated feedback system. The engineers have its basic principles worked out; it’s mechanical, you know; nothing to get superstitious about; and man can always improve on nature once he gets the idea. There is a magazine title on my desk that reads machines are getting smarter every day. I don’t deny it, but it’s life I believe in, not machines.

Maybe you don’t believe there is any difference. A skeleton is all joints and pulleys, I’ll admit. And when man was in his simpler stages of machine building in the eighteenth century, he quickly saw the resemblances. “What,” wrote Hobbes, “is the heart but a spring, and the nerves but so many strings, and the joints but so many wheels, giving motion to the whole body?” Tinkering about in their shops, it was inevitable in the end that men would see the world as a huge machine “subdivided into an infinite number of lesser machines.”

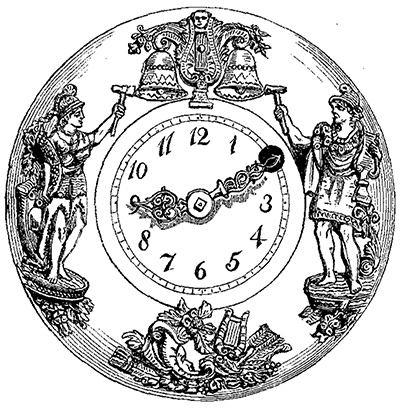

The idea took hold with a vengeance. Little automatons toured the country—dolls controlled by clockwork. Clocks described as little worlds were taken on tours by their designers. They were made up of moving figures, shifting scenes, and other remarkable devices. The life of the cell was unknown. Man, whether he was conceived as possessing a soul or not, moved and jerked about like these tiny puppets. A human being thought of himself in terms of his own tools and implements. He had been fashioned like the puppets he produced and was only a more clever model made by a greater designer.

Then in the nineteenth century, the cell was discovered, and the single machine in its turn was found to be the product of millions of infinitesimal machines—the cells. Now, finally, the cell itself dissolves away into an abstract chemical machine—and that into some intangible, inexpressible flow of energy. The secret seems to lurk all about, the wheels get smaller and smaller, and they turn more rapidly, but when you try to seize it the life is gone—and so, it is popular to say, the life was never there in the first place. The wheels and the cogs are the secret and we can make them better in time—machines that will run faster and more accurately than real mice to cheese.

I have no doubt it can be done, though a mouse harvesting seeds on an autumn thistle is to me a fine sight and more complicated, I think, in its multiform activity, than a machine mouse running a maze. It leaves a nice, fine, indeterminate sense of wonder that even an electronic brain hasn’t got, because you know perfectly well that if the electronic brain changes it will be because of something man has done to it. But what man will do to himself he doesn’t really know.

I am older now, and sleep less, and have seen most of what there is to see and am not very impressed anymore, I suppose, by anything. what next in the attributes of machines? my morning headline runs. it might be the power to reproduce themselves. I lay the paper down and across my mind a phrase floats insinuatingly: “It does not seem that there is anything in the construction, constituents, or behavior of the human being which it is essentially impossible for science to duplicate and synthesize.” On the other hand the machine does not bleed, ache, hang for hours in the empty sky in a torment of hope to learn the fate of another machine, nor does it cry out with joy nor dance in the air with the fierce passion of a bird.

All over the city the cogs in the hard, bright mechanisms have begun to turn. Figures move through computers, names are spelled out, a thoughtful machine selects the fingerprints of a wanted criminal from an array of thousands. In the laboratory an electronic mouse runs swiftly through a maze toward the cheese it can neither taste nor enjoy. On the second run it does better than a living mouse.

From “The Bird and the Machine,” which appeared in the January 1956 issue of Harper’s Magazine.