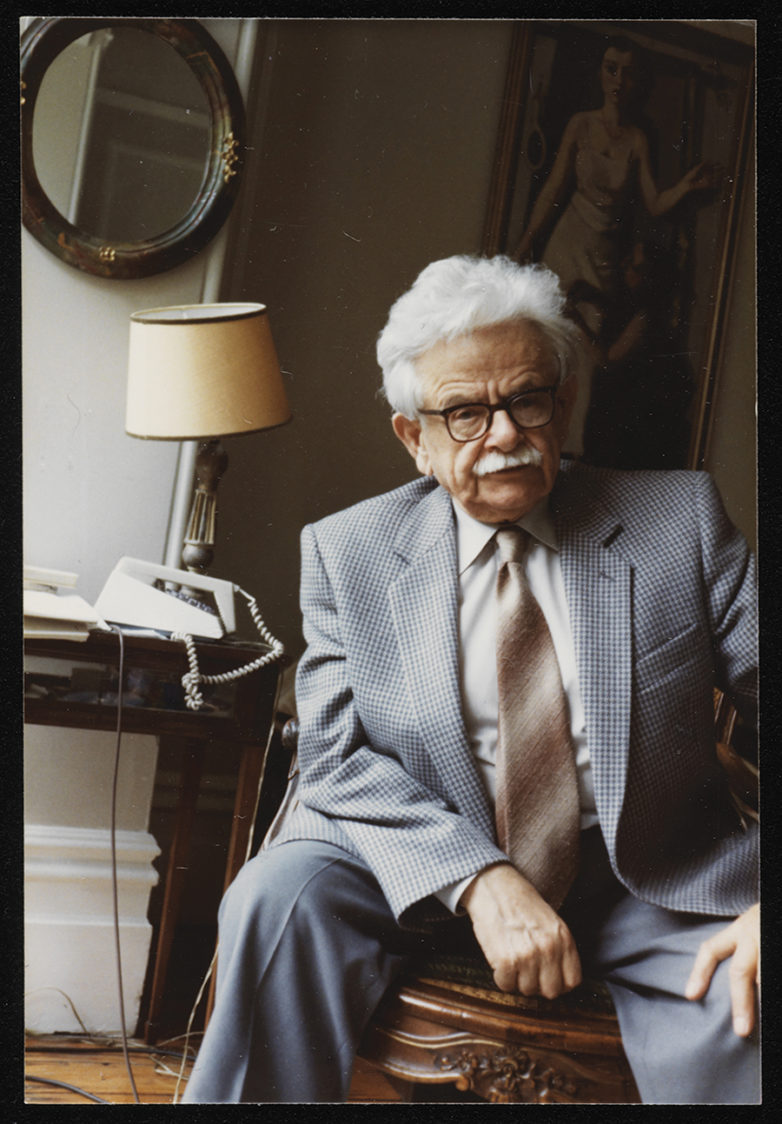

Photograph of Elias Canetti, 1983, by Marie-Louise von Motesiczky © Marie-Louise von Motesiczky Charitable Trust. Courtesy Tate Archive

In 1980, the year before Elias Canetti won the Nobel Prize in Literature, Susan Sontag described him as a writer whose work is “confidently rooted in a certain rich Central European culture” yet “hard to place, even willfully placeless.” Canetti’s effort, she continued, “has been to stand apart from other writers. . . . Canetti is, both literally and by his own ambitions, a writer in exile.”

Even today his work is not widely known, and the idea persists that Canetti is unapproachable. Kudos then to Joshua Cohen, to the numerous translators, and to the publisher for I Want to Keep Smashing Myself Until I Am Whole (Picador, $20). This brilliant selection of Canetti’s writing serves as a gateway to a figure whose oeuvre is, as Cohen writes in his introduction, animated by an “Ovidian ideal of mutual imagination and inhabitation,” a “metamorphic ability ‘to becom[e] everyone,’ ” and a “protean desire ‘to experience others from within.’ ”

Canetti’s range astonishes. He wrote one extraordinary modernist novel, Auto-da-Fé, in which, as Cohen puts it, “a reclusive Viennese bibliophile and Sinologist . . . ends up torching his own vast library, and in the process immolates himself”; a study of mass psychology, Crowds and Power; three plays; and in later life, a series of riveting memoirs. He also kept various and wide-ranging notebooks, or Aufzeichnungen. It was through these notebooks, Cohen suggests, that Canetti “finally came to terms with the principle of incompletion, and to understand it not as a failure of the artist, but as a triumph of art—specifically, as a triumph of art over death.”

Canetti’s evocation of his early childhood in Ruse, Bulgaria, is Tolstoyan in its lucidity and immediacy. Whether describing his grandfather’s butica (shop), or telling local stories about sledding over the frozen Danube, fearing the attack of ravenous wolves, or the Roma who visited the family compound, he deliciously conjures a vanished world. His parents, having met in Vienna, spoke to each other in German; the household spoke Ladino, the language of Sephardic Jews; and the servant girls spoke Bulgarian. When he was still small the family moved to Manchester, where his father died suddenly, and then to Lausanne and Vienna. After some years in Zurich, he moved to Britain, where he stayed until the early Seventies.

Canetti lived through the upheavals and displacements of the twentieth century. He embodies the intellectual intensities of modernism and interwar Vienna: He recalls Karl Kraus’s lectures (Kraus was, it seems, as popular as the Beatles), at one of which he met his future wife. He records his encounters with Thomas Mann, Robert Musil, Hermann Broch. And he expounds movingly and wisely about what matters to him most—art and death, as in this passage from his unfinished work Das Buch Gegen Tod:

Write until your eyes close, or the pencil falls from your hand; write without wasting a second or thinking about what and how it should sound; write from a feeling of untapped life that has become so huge that it is like a massive mountain gathering inside of you.

Auto-da-Fé as excerpted in the new collection remains ripe for analysis, albeit a product of its historical moment. Both the force and strangeness of Crowds and Power emerge in the sections Cohen has chosen to include: as an enterprise it hearkens back to a less specialized era in which an erudite and scrupulous amateur could tackle vast subjects on his own authority. This volume lacks Canetti’s dramatic works, but there is more than enough without them. Personally, I’ve copied out citations from the notebooks—a treasure trove, as Cohen writes, of “traditional aphorisms, feuilletonesque caricatures, mock-Socratic dialogues”—and have ordered the memoirs entire.

In his moving memoir Stay True (Doubleday, $26), the New Yorker staff writer Hua Hsu portrays, and in one section addresses, a companion from his youth who has stayed with him in absentia. Though far more than a straightforward posthumous tribute, Hsu’s account is structured around the violent murder of his close college friend Ken in 1998, the summer before their senior year at Berkeley.

The book is also the account of a particular pre-internet time of handmade zines and personal discoveries: “Maybe those were the last days when something could be truly obscure,” Hsu muses. As the Californian son of Taiwanese immigrants, he set off for Berkeley endeavoring to shape and articulate his identity: “I was an American child, and I was bored, and I was searching for my people.”

When Hsu first met Ken he hated him: “All the previous times I had met poised, content people like Ken, they were white.” Ken was “mainstream”: handsome, well-mannered, charming, he joined a frat early on, listened to music Hsu despised (Pearl Jam, Dave Matthews Band), and seemed to feel at ease in his skin. Here Hsu distinguishes between the immigrant anxieties of many Asian Americans like himself, and the experiences of some Japanese Americans whose families had been in the United States for decades. “The Japanese Americans I’d grown up around had parents who were into football and fishing,” he writes, “grandparents whose stories of the internment camps were recited with no trace of accent. Some of them had never even been to Japan.”

These distinctions did not impede the boys’ friendship; they bonded by becoming smokers together. As Hsu observes, “some friends complete us, while others complicate us.” Ken, perhaps, did both. Hsu relates his own college experiences, through which Ken’s presence is threaded: Hsu and Ken interact in ways that shaped his sensibilities and, to a degree, his interests. Though Ken had some awakenings about his identity, Hsu was the more overtly political: he protested against Proposition 209, grew interested in the Black Panthers, and created several zines.

Ken was abducted from his off-campus apartment after a housewarming party in July 1998. First locked in the trunk of his own car, he was then robbed and shot by a couple and another man they’d just met. In time, Hsu and others attended the arraignment and marveled that “the defendants looked vacant and desiccated.” But Hsu makes clear that these people, and the details of the violence to which Ken was subjected, are not his preoccupation. Rather, he’s interested in Ken’s ongoing presence in his life, as reflected in the fact that “my journal contained my half of our continued conversations. . . . Writing offered a way to live outside the present.”

There’s the inevitable implication that Hsu’s subsequent choices—to write a thesis on “representations of race in American films,” help organize a conference on the prison industrial complex, tutor inmates at San Quentin, and attend graduate school at Harvard—carry in them his friend’s influence. In grad school, he talks to a therapist about what happened and grapples with his irrational guilt. By the time he concludes his therapy, and the book, he’s conscious that “the true account” of his friendship with Ken “would necessarily be joyful, rather than morose, and surrendering to joy wouldn’t mean I was abandoning you. . . . It would be poetry and not history.”

“Piece of Cake,” by Angela Fama © The artist

The English writer Gwendoline Riley’s acerbic novels are decidedly “the true accounts” of her protagonists’ relationships, in particular romantic and familial; but rarely are they joyful. Indeed the very idea of joy seems to have been banished from her characters’ lives: it’s as if Jean Rhys had been rendered middle class and had gotten a modest grip on her drinking while remaining messed up. This makes for surprisingly eloquent and compelling reading.

Now in her forties, Riley published her first novel twenty years ago while still at university, and has been consistently highly acclaimed in Britain. But her fiction has not been widely published in the United States. New York Review Books is bringing out two of her recent novels at once: a reissue of First Love (NYRB, $16.95), originally published in 2017, and My Phantoms (NYRB, $16.95), from last year.

Both novels, like Riley’s other fictions, are narrated in the first person by young women whose elisions speak volumes, and whose judgments are, in the Flaubertian tradition, at once unsparingly honest and impressively without compassion. It’s sometimes difficult to discern between haplessness and evil: all the characters these women describe are detestable to varying degrees.

In First Love, Neve, a writer in her thirties, has unceremoniously married an older man named Edwyn. Her father, from whom she was estranged, has recently died. She cries while reading a list her mother made for the solicitor of the things her father had done to her: “Slapped, strangled, thumbs twisted. Hit about head while breast-feeding. Hit about head while suffering migraine. Several kicks at base of spine. Hot pan thrown, children screaming.” To this Edwyn responds, “Oh, she kept a list, did she?”

Riley’s brilliant ear for dialogue falls in an excellent British literary lineage that includes Henry Green and Barbara Pym. We understand much about the ill-tempered Edwyn from his speech, veering as he does between sickly endearments (“Lovely Mrs. Pusskins! Prr prr”) and manipulative abuse. “Christ, I’m sick of all this hatred and rancour. I’ve never had this in my life before. You had it all the time, you’re used to it,” he says at one point, harping about an evening almost two years ago when Neve vomited after a party. But we understand that Edwyn is not wrong, and that Neve has survived considerable darkness. She doesn’t confide in the reader and doesn’t talk about herself at all. We must discern her outline from her encounters with and opinions of others.

She describes her father as “a tyrant child” and “the restless bully about town,” and notes that “my brother stopped going to see him when he was fifteen, after my father punched him in the face.” Her mother’s reaction was to beg her for “just one more year . . . just keep the peace, please.” Hence, perhaps, her contempt for the woman with whom she has nonetheless kept in touch, unlike her brother or father. Neve’s mother, weak and brightly smiling, is also impeccably conveyed. “This cover-seeking—desperate, adrenalised—had constituted her whole life as far as I could see,” Neve says, then adds, “Perhaps I should be more moved by her than I am.” But her mother’s failure to protect her children is almost as inexcusable as her father’s violence.

“Considering one’s life requires a horribly delicate determination, doesn’t it?” Neve muses. To experience the ghastliness of daily life with Edwyn alongside the dreadfulness of her childhood is to understand that things are better than they used to be. Which may not be saying a great deal. But when Edwyn says to her in bed, “I love you. Little one. Little Neve. I do,” her response is: “I could have been asleep. I let some peaceful seconds pass, before I said it back. ‘I love you.’ ” How the reader feels the weight of those seconds and all that they may hold.

Bridget in My Phantoms is older than Neve; she, too, lives in London with her boyfriend, hails from the north of England, and grew up with her mother after her parents’ divorce, regarding visits with her father as “something to be weathered,” noting, “I’m not sure I even thought of him as a person, really. He was more just this—phenomenon.”

Instead of an estranged brother, Bridget has a sister, Michelle, settled not far from their challenging mother in Liverpool. Bridget’s relationship with her mother, Helen, known as Hen, is at the novel’s heart: “She was the fairy-tale misfit. The changeling. She only had to wait and be brave.” Once Bridget is grown up, Hen is “never short of engagements”—but in spite of such socializing she has no friends, except for a gay man named Griff.

Mother and daughter struggle to communicate, keeping their distances: for years, “at Christmas and on her birthday, I sent a card and a book.” Hen then initiates a tradition of coming to London for her February birthday to have supper with a reluctant Bridget, who will not allow Hen to visit her flat or meet her boyfriend. Bridget is often sour with her mother, and always withholding: “I didn’t, as a rule, talk to her about anything that mattered to me. Why upset her by talking about things she couldn’t understand or enjoy?”

As with First Love, the parents’ toxic relationship—the mother’s masochistic manipulations and the father’s grotesque sadism—has abiding ramifications. In a rare significant conversation between mother and daughter, Bridget asks Hen about long-ago accusations of sexual abuse brought against her ex-husband. Hen waffles and Bridget says, “It really didn’t matter, to me . . . it was as if I’d never brought that business up; as if it had never happened.”

As Hen’s health deteriorates—first her knee, then her brain—Bridget tries to titrate how much frankness her mother can tolerate. There is even, miraculously, a dinner at Bridget’s home with her boyfriend John and a man whom Hen met on a trip to Portugal. John (an analyst, we learn only belatedly) observes that Hen is “unyielding” that evening. “She’s clearly frightened of engaging. That’s a sad thing. . . . Here’s a better way to put it, she was in an a priori reality. . . . And that reality was not going to yield to another reality.”

John is more direct than any other character in My Phantoms or First Love, but he opines only this once, and his observation, while elucidating, changes nothing. Riley’s bitter precision, replete with dark humor, offers perhaps more reality than our saccharine culture wishes to contend with, and this may explain why her work is not yet better known in the United States. But surely we do not want to be like Hen, defensively trapped in an “a priori reality”: though we may long for a fairy tale, our world is littered with maimed psyches and flawed relationships. We are fortunate when so gifted a writer illuminates, with such nuance, what life is like.