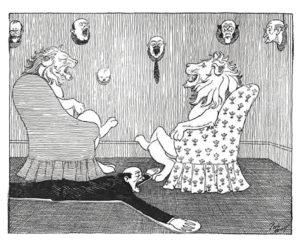

St. Francis once converted a wolf to reason. The wolf of Gubbio promised to stop terrorizing an Italian town; he made pledges and assurances and pacts, and he kept his part of the bargain. But St. Francis only performed this miracle once, and as miracles go, it didn’t seem to capture the public’s fancy. Humans don’t want to enter into a pact with animals. They don’t want animals to reason. It would be an unnerving experience. It would bring about all manner of awkwardness and guilt. It would make our treatment of them seem, well, unreasonable.

The fact that animals are voiceless is a relief to us, it frees us from feeling much empathy or sorrow. If animals did have voices, if they could speak with the tongues of angels—at the very least with the tongues of angels—it is unlikely that they could save themselves from mankind. Their mysterious otherness has not saved them, nor have their beautiful songs and coats and skins and shells, nor have their strengths, their skills, their swiftness, the beauty of their flights. We discover the remarkable intelligence of the whale, the wolf, the elephant—it does not save them, nor does our awareness of the complexity of their lives. It matters not, it seems, whether they nurse their young or brood patiently on eggs. If they eat meat, we decry their viciousness; if they eat grasses and seeds, we dismiss them as weak. We know that they care for their young and teach them, that they play and grieve, that they have memories and a sense of the future for which they sometimes plan. We know about their habits, their migrations, that they have a sense of home, of finding, seeking, returning to home. We know that when they face death, they fear it. We know all these things and it has not saved them from us.

Anything that is animal, that is not us, can be slaughtered as a pest or sucked dry as a memento or reduced to a trophy or eaten, eaten, eaten. For reasons of need or preference or availability. Or it’s culture, it’s a way to feed the poor, it’s different, it’s plentiful, it’s not plentiful, which makes it more intriguing, it arouses the palate, it amuses the palate, it makes your dick bigger, it’s healthy, it’s somebody’s way of life, it’s somebody’s livelihood, it’s somebody’s business.

Agriculture has become agribusiness, after all. So the creatures that have been under our “stewardship” the longest, that have been codified by habit for our use, that have always suffered a special place in our regard—the farm animals—have never been as cruelly kept or confined or slaughtered in such numbers in all of history. Aldo Leopold argues that wild animals and domesticated animals have different moral statuses—domestic animals are not free and therefore are unworthy of our regard. Catholic moral textbooks instruct that we have no duties of justice or charity toward animals; our only duties concerning them are the proper use we make of them. But large-scale corporate agribusinesses, enjoying fat federal tax breaks, don’t need to have their interests defended by effete ethical rationalizations. Factory farmers are all Cartesians. Animals are no more than machines—milk machines, piglet machines, egg machines—production units converting themselves into profits. They are explicitly excluded from any protection offered by the federal Animal Welfare Act, an act that is casually and lightly enforced, if at all, by the Department of Agriculture: “normal agricultural operation” precludes “humane” treatment, and anti-cruelty laws do not apply to that which is raised for food.

The factory farm today is a crowded, stinking bedlam, filled with suffering animals that are quite literally insane, sprayed with pesticides and fattened on a diet of growth stimulants, antibiotics, and drugs. People will stop eating veal only if they think they will get a killer disease if they don’t. Once assured by the government that there is no further need for alarm, they will be back in the spotless supermarkets, making their selections among the sliced, cubed, and shrink-wrapped remains, which have borne no resemblance to living things in our minds for some time now. They are merely some things, in a different department from the toilet bowl cleaner. The supermarket has never been a place where one thinks—Animal.

From “The Inhumanity of the Animal People,” which appeared in the August 1997 issue of Harper’s Magazine.