A departure yard in Chicago (detail), December 1942, by Jack Delano. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Leave the two men stranded along the railroad tracks outside Chicago, not far from Michigan City, Indiana, during what would eventually be called the Great Depression, hunched together down in the weeds, resting their feet, smoking and looking out at the lake, which that day was as gray and roiling as the clouds, driven by wind from the north. It was close to Christmas and winter seemed eager to arrive.

One of them, the tall one, wore a massive oversize grenadier-style coat—a chinchilla of dark blue, double-breasted with a number of missing buttons. The other, the shorter one, named Buster, a ridiculously long leather mackinaw with moth-eaten shearling lining over an old cossack jacket he’d picked up at a charity shelter on the South Side earlier that fall.

The tall one was named Zaccheus and had a nose that had been broken a couple of times. The first break came from sparring with a kid named Jackie. There’s supposed to be a diplomatic aspect to sparring, he explained to Buster. Out of respect, two training boxers approach each other carefully when they spar and take care to avoid injuries. Closer to a fight date, it might get rough. But this kid Jackie was new—just starting off—and new kids can be stupid dangerous. He had something to prove and Dee, my trainer, was off answering a phone call, otherwise he would’ve kept the kid under control. I went easy and told him to toss me everything he had, and that’s when he broke my nose. I mean this kid had been soaking his knuckles in brine to toughen them up—rumor had it that Jack Dempsey soaked his knuckles—and he landed one of those lucky flash punches, quicker than expected, and it broke my nose so that I had to reset it myself in the gym bathroom, he explained. The second time I got it broke was in a pro fight up in Buffalo during a blizzard when I had to fight this lunkhead calling himself Irish Jack who had arms as big as hams and tossed punches the way you throw meat off a wagon. The arena that night was short on coal and our gloves were like blocks of ice, he told Buster back when they were getting to know each other, sharing bottles and stories.

Your namesake, the original Zaccheus, was this knobby, ugly little tax collector fuck who climbed up into a tree to watch Jesus do his thing. Instead of kicking his ass, Jesus called him down, took him under his wing, and defied common sense and all that, Buster explained one night.

Admit that Zac’s situation is similar to your own. Try to avoid the particulars. Or remember the wrong particulars, if that helps. Giving up can be a way of giving in. Letting go can be a way of getting. Quitting a story is like filling an aching tooth.

The one named Buster was hefting his coat up and working to tighten the rope he was using as a belt. His stomach was grumbling. He had been halfway through telling a story he’d begun a few miles back about a bum kid named Lockjaw who had saved a train from collision at State Line junction near Hammond, Indiana, not far from where they were standing. That’s how my uncle told it, he said. He worked the junction and was there to see it.

To strand them standing there forever would be nothing short of catastrophic, you tell yourself. Both men are quitters, and both of them are resigned to fate.

Zac quit before a pro fight at the Marigold Gardens, on the way to the ring. The tinny roar of the crowd and thick cigar smoke siphoned down the brick corridor. He was wearing his wife’s satin red robe as a getup, his boots laced tight, while his opponent that night, Rocking Rudy, strode ahead of him. On an impulse he’d never be able to explain to himself, he turned right instead of left, took the back exit into the parking lot, and walked away from the ring for the rest of his life.

To quit the story would be to let Buster have the final word. Look, Zac, the way I see it, we’re inside this tyranny no matter what, he’d say, scratching a match on the side of a hot slag car, lighting his smoke before launching into his theory that to want to win anything—as bad as Zac had wanted to win that title—put you into a tyranny of expectation, the same expectation that you, Means, were feeling as you watched Zac turn to his friend and say, You’re full of shit, Buster, with all of your fancy words, and then you listened as Buster said, What words? And you heard Zac say, Tyranny is a bullshit, big shot word, and you watched as Buster shook his head and spit off to the side before explaining that one word wasn’t any more highfalutin than any other. (You struggled to catch the right tone, his learnedness combined with the lingo he had picked up from Zac, who had picked up his own way of talking during his years at the boxing gym, where every ten minutes his manager and mentor, Dee, would check his stopwatch and shout time in, meaning time to begin a round of exercise—working the table or shadowboxing—and then time out when three minutes were up, so that it was time in, time out, time in, time out, time in, time out as they worked through the stations day after day, a rhythm broken only when Dee came over to impart wisdom, saying, Lower that side of your shoulder and keep your guard up, or, The only way to win a fight is not to think about winning it, or, You gotta be where you’re at to get where you’re going, or, most famously, The only way to get the prize is to stop wanting the prize and let the prize be wanting not to have the prize in the first place.)

You watched early in the fall as a cop, Sergeant Pulaski, picked up Zac on a charge of vagrancy and then, in a fit of kindness, offered to pay him a little bit to stand in a lineup, shoulder to shoulder with others of his likeness—tall men with gaunt weathered faces and droopy eyelids—not because he was accused of the crime but because he looked the part. I was put up before judgment for a crime I didn’t commit, knowing I didn’t commit it, and aware that I was there as a token of others who looked like the one who did commit it, he said as he and Buster trudged through East Chicago, past the rows of tenements, street vendors crowding the sidewalks, and then up the hill at Ninety-fifth Street and onto the tracks that led to the Iroquois steel mill where the Calumet River fed into the lake—you’d make note of that bridge, the shack with the tender—and then, as they walked, he began explaining to Buster how his father had worked in steel and could read a mill by the smoke, tell you what was being cooked, or not cooked, or if the thing was heating up or down just by the type of smoke that was or wasn’t coming out.

You work to solidify Zac and Buster inside this landscape. You push them to get a handle on their own destinies and, hopefully, in doing so, to become major characters. You urge them to head to upper Michigan. You imagine creaking floorboards in the entry to a saloon on a snowy night. The icy shore of Little Traverse Bay in wan winter light. A mansion on a hill surrounded by a spikenard fence. Such are the images you see ahead for these two figures you’ve conjured out of the past, out of the dim darkness of memory, until you see, clearly, that on his own and without your help, Zac has become hell-bent on making it to Petoskey where, he claims, he has an uncle with a mansion and a fortune who will stake him a part of his coal company or his shipping business which you know—in your heart of hearts—is most likely a MacGuffin he’s created to get himself up there so he can find the mansion empty and boarded up, and then, on a binge, he’ll be swept off the stone pier during a storm because that point on the map is lodged inside his delusional memory, and all memory is delusion surrounded by need. Buster understands all this as he listens to Zac saying, We’ll go see my uncle up in Petoskey and leave this fair but brutal city behind.

(Nelson Algren once wrote an article for The Saturday Evening Post about the police: “He doesn’t know he’s healthy. He thinks he’s sick. And from this dangerous illusion his life is pervaded by a conviction that he is inferior. Between the image the world approves and the fantasy he indulges, he drives to the hour when the approval is made official by the badge on his breast; and immunity is granted him to indulge such fantasy. Now at last those who have made him toe the mark are going to have to take their turn at toeing.”

There are protests going on in the streets of Brooklyn, and that makes you want to quit the story, to abandon them there. You’re aware that to get them up to northern Michigan on the Pere Marquette railroad would involve sheer luck, catching the train that is heading to the Grand Rapids line, and avoiding the line you’ve taken a hundred times to Kalamazoo, feeling the lame yank and pull of the Amtrak as it passes the old mills. They’ll huddle in a boxcar. They’ll leap off into snowdrifts. They’ll spot the cozy lights of a small town. They’ll eat a slice of pie at a lunch counter. A kind woman. Darkness pressing the windows.

When you were a teenager, spending the summer in northern Michigan, you and a kid named Bud Pickett hopped a train on the tracks that ran along the shore of Little Traverse Bay, catching it along the straightaway. You ended up face-to-face with a cop at a grade crossing. The cop chased the train and caught you and took you to the jail in Harbor Springs. Grandma Means arrived to bail you out. Stately and prim. Gnarled fingers clutching the handle of her cane. You’ll give Buster her locutions, her way of speaking.)

Compress the trip north into a few sentences: inside the boxcar, a pile of packing hay in one corner, Zac sucking on the mouth of a bottle, asking Buster to keep talking, to finish the story he’d started about the bum named Lockjaw.

A switchman demonstrating the stop signal with a fusee in Calumet City, Illinois, January 1943, by Jack Delano. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Lockjaw was a bum suffering from tetanus, staying in a flop in Pittsburgh. There’s a doctor in the story. His name was Williams. The flophouse cots were stained and rusted. Williams jabbed the antitoxin into the boy’s arm. Downstairs, he stopped in the lobby to speak with the manager, Bud, who sat behind a chicken wire cage. Bud said the kid wasn’t going to stick around long enough to get himself cured doctor-wise. Williams touched his cap and nodded. Bud stuck a receipt onto a pointed spindle. Williams left the building and stood in the street. He heard the sound of a train. It filled him with sadness. (What the fuck does this doctor have to do with the story, Zac might say in the boxcar. What are you getting into here?)

It’s later and Dr. Williams is at the dinner table. His wife, who is unable to have children, is speaking to him about God. God doesn’t want you to tend to flophouse men, dear. You should focus on delivering babies. In another scene, Williams is getting up in the morning, heading out on a call, the light dim as it pushes through the coke smoke and morning inversion fog, alighting softly upon sullen clapboard houses along the hill, striking the church that looms at the top, hulkingly awkward and out of place. The sun draws itself along the keen edge of tracks down which a train runs, warning a grade crossing with two longs and one short, a sound so routine that most of the time Williams, leaving his house for an early call, wouldn’t hear it because, frankly, to hear it would be to become, Buster would say, seized up with an unbearable sadness. That particular morning, he heard the train and crossed Hamlet Street and mounted the hill, heading to yet another millhouse in which a patient was waiting, moaning while the men on the front stoop sat and smoked and looked absently out at the street, holding still around the fear—because the terror of it was immense in them—the way they became still when making a big pour. The old doctor felt the edge forming, Buster would explain. He was feeling that fucking edge that gave him the urge to quit. He felt his professional bearing in the stroke of his heel on the pavement. He would bark orders and some kid would get a pot of water boiling. The kitchen table would be cleared and covered with linen for the patient to lie on. Then he’d reach in and rotate, if necessary, to clear the cord because, for some reason, these early morning calls almost always involved a problem, rarely a good old cephalic presentation, most often a breech or a preeclamptic caesarean, he thought as he walked, feeling his attention split and turn, first to the train and then for a moment to the kid in the flophouse yesterday. The sun plunged down and the windows glinted and the birds chirped as he walked past the men on the stoop, tipping his hat, lifting his bag a bit too quickly, by way of indicating his intentions, and in doing so causing the muted soft clink of his armamentarium—Buster would, if you let him, use that word—his forceps, his specula alongside the scissors, pessaries, and clamps against rheostats, with his scalpels silently tucked tight in the leather case. He crossed the threshold into the cramped house—a faint cabbage smell along with furnace coal and steaming water—while behind him, outside, still within range, he heard the train call him one last time, and then he was mounting narrow stairs toward the cries, woody and softer than expected, tightening around the task at hand, drawing his attention away from everything else.

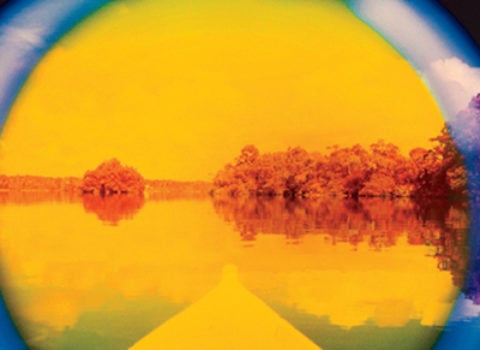

A bung scent in the wind. Hundreds of miles of water to the north as both men face it, looking and smoking and squinting.

Dee clicked his stopwatch and called out for them to go to the next station. They sparred once a week. It was a fucking jab only a beginner would throw. Everything he had was in that single punch. No style, just force. Dee came back from his office and told the kid to go easy. Zac had the kid on the mat with a combination. (In his classic study The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman coined the phrase “working consensus,” which was then referenced in another classic study, Body & Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer by Loïc Wacquant, who applied the theory to his study of gym life, which is part of the fuel you want to use to imagine the story, giving it to Zac and his sparring scene and then to the two men, staggering down the tracks out of Chicago, working to keep each other alive, to buck the odds.)

Go back in time to square the circle of actions. Dig into the particulars of Zac’s life in fits and starts. Sleeping in a flop one night and out on the street with a bottle the next until one winter evening he was slouched against a wall somewhere near the old water building on Michigan Avenue when Buster appeared—just as drunk and on the bum as he was—and crouched down to offer a bottle to his lips, an act of pure grace, speaking in his strange way, drawing from his book learning (and sounding a lot like your Grandma Means), until later that night he found himself asleep down in a thicket of weeds where there was a Hooverville encampment of lean-tos and shacks close to the lake, close enough to hear the slosh of water, not far from where the beautiful scalloped stainless steel of the Gehry bandshell sits in so-called Millennium Park, about twenty yards from where you and Geneve sat on a bench a few years ago, before the pandemic, and you talked about the men in the story you were catching, and how you imagined they slept tenderly against each other in a fetal position, trying to share heat and keep warm.

Nobody wants a boxing story these days. The violence is what most people think about when they think about boxing. This story starts long after his time training in Woodlawn—the intimate sense of mission that held members of a boxing club together, the hours spent shadowboxing and tenderly helping one another on the table, holding ankles and trading tricks and techniques with an easygoing camaraderie that would sound strange and retrograde at this moment in history, in relation to the people marching and putting their lives on the line. But those men in the gym were all races and colors, too. Loïc Wacquant was white and French and trained alongside black fighters in Woodlawn, South Side Chicago. This future would seem delusional to these men. Zac would throw his arms in the air and ramble on and on and on about how his father had worked the mill beside people of color. He’d say: Yes, sir, united by the union these fuckers poured steel alongside one another, you see, and then he’d argue that when you were working at the mill, tending to a bucket on the floor, gazing through goggles and soot, sweating like a pig, when one small step meant death, you didn’t care the color of who you were with so long as they had your trust. One slip meant an explosion, a rain of sparks, and death. If given a chance, he’d go on and on and on about the men who manned the machines that flipped the hot ingots off the rollers. You know, he’d say, with all those levers that you had to throttle back and forth, using your gut and skill to guide yourself, with no fucking clue whose fingers were doing the work, he’d say, and then you’d let him ease up, feeling the urge to quit the story. You’d let him stop talking because you’d know it’s impossible to bring a voice like his, all tight nasal, all failure and despair, straining angrily against the dream, stuck in those forlorn early days of economic downfall, as much as you’re stuck in your own.

Strand them like holy fools! Amplify the way the past is disposed in favor of the future. Avoid arrival to northern Michigan, lying on a flatbed, or in a coal car, or in the doorway of a box, staring up at the cold stars above the smear of farmland flattened under a foot of snow, smoothed over by cool moonlight until stubby, second-growth pine trees, burned to stumps, appeared near Horton Bay. Avoid watching the two of them leap from a train—that pie, that café, the warmth of that counter and the kind lady behind it—and instead let them fall into wonderful slumber, curled exhausted in a snow bank, giving in to the subzero night, as what’s left of the heat of their bodies quivers through the cloudless sky and into the eternity of dark space, which could be the final image of the story. Brittle stars shaking and settling into pointed brightness, casting a frail light down onto their frozen humps, which snow covers up slowly, like the back of the horse in the Chekhov story, too tired and weary from pulling his cart to offer a riffle of his thick, clotted mane or a small snort.

Don’t give Zac a chance to stop eating blueberry pie in the café, or at a kitchen table, wiping the crumbs from his lips and saying, You only get an opportunity to quit the way I did once in your life. Or perhaps: You can only quit big-time once and that’s it, the big quit. You know, Buster, the way I see it, when I walked away on that fight I walked away for the first and last fucking time, if you know what I mean, because a person only has a chance to quit like that once in a lifetime. Let me tell you, it felt good to quit that way. It had to be done, I now see, because it was my big chance, and that means my big chance not only to win the big prize and lift my gloves in glory but also, the way I see it, to go out in a way that was just as big, and then he’d take another bite of pie and a sip of warm coffee and watch the young lady at the sink rubbing a dish towel into her tender, chapped hands, an image that would remind him of his own hands pushing the bar on the exit door, releasing him into the rear parking lot where a black sedan idled under the single street lamp emitting just enough light to illuminate two thugs, two second-rate gangsters who, as luck would have it, were dozing with their hats pulled down.

No, before you quit you have to at least let them start walking so Buster can go on with the story he began telling back in East Chicago, his voice rising a little along with the wind—and explain the nature of those switches, because he had done a little time on the railroad after he left Pittsburgh, or maybe his old Uncle Ned had worked the Canadian Pacific Railway before going to the State Line junction to work the tower (you haven’t decided), and he’d explain that there were rods that ran from the tower out to the tracks, and that you’d throw the switches with big levers that drove the rods, and that they froze up from time to time, and then he’d go deeper into the mystery of the great juncture of the tracks, a crossing point of future destinies—the men felt. It was part of the job, that feeling. Part of the job was to gaze out the tower window and to sense the mythic aspect that was inherent in all that tonnage being shifted from one set to another, or taking their lunch buckets down to watch the inbound trains approaching the arrays—nothing better than four trains coming through at once, each one avoiding the other, or, for a few minutes, on approach, drawing a bead on one another, showing the potential for collision touched with the grace of avoidance. The men were fully versed in the stories of collisions, and a few had witnessed the aftermath, or studied postcard images of the great crashes of yore. They knew about hotbox burnouts and overheated journal bearings, and the odd, almost supernatural head-ons that ended with one engine neatly atop another, sliding up and over, defying the bulk, seesawing like a duck probing for food. Not to mention the crown sheet failures, overheating due to low water, a misread dial, a sleeping crewman, blasting out mounds of twisted superheater tubes. The junction was foolproof with checks and double checks but it wasn’t—the men liked to say—idiotproof. The only thing idiotproof, Buster might say if you let him, is a coffin lid. You shut it, it closes and stays closed. The idiot that day was a man named Jed Row, a boozer who fucked it up, who set a west- and an east-bound, one of them baked up good and hot on the brilliantly straight and clean line that—Buster would explain—teased all of the engineers, held itself out as raw temptation to get the coal screwing wildly into the firebox, throbbing and hot, the heart of the beast roaring beyond speed limits. All railmen understood the paradox, the truth that they hate switch arrays—or, using the appropriate parlance, turnouts—because of the stress they put on the wheels, and the ugly, abrupt shifting from one line to another. You’d let Buster spin into the way Jed got the switches into the wrong position and then ramble on about how engineers dreaded head-ons whereas conductors, in their secret hearts, dreaded telescoping accidents, and all remembered the great accidents at Camp Hill, Revere, and, above all, the Mud Run disaster where—he’d add—sure, the cars were made of wood rather than steel and scoped into each other with horrific neatness while at the same time the engineers walked away from the wreckage to work another day. But when the idiot tried to pull the lever he felt resistance along the line, a rebuff of his efforts, staring dully at the big ratchet handle, and then, as protocol dictated, sent a maintainer kid out to check the rod, which most likely had frozen up in the cold, and the kid went out and found another half-dead hobo—Lockjaw—having a seizure, all control lost, Buster would explain, and then he’d shift back to general talk about the junction, about the way it stood silent, empty and quiet when things were dead, suspended between ingoing and outgoing, with the dew-wet rails burning like etched glass in the rising sun, ticking and gathering heat while everything waited for action and gave over to the sense that out there, in the beyond, trains were moving across the land.

Buster had the rest of that story in his mouth. He could feel it as they stood in the weeds and looked at the lake. He inhaled smoke and looked at Zac, who had a fine, wide face and a high brow and had, as he took off his hat and ran his hands through his hair, a bemused look that brought his eyebrows up. The story had to be told because it was only half finished and in his throat.

In the boxcar—huddled in the packing straw, trying to stay warm—Buster would continue his story. There was something holy—he’d say—seized-up somatic muscles, hopeless and hidden, the tension between mind and flex, the bending back and up with the paradoxical combination of rigid and flexible, he’d explain, saying it was Williams’s point of view, all this. Zac would grunt and pop the dry bottle off his lips. He’d seen men with the DTs, he’d seen men doing St. Vitus’s dance with an odd elasticity, eyes rolled back to the whites. He was shivering and imagined logs shifting in a fire, a hot stove radiating warmth, the suck of air through a flue. Buster shivered, too, and drew the collar of his outer coat up around his neck. The door to the boxcar was jammed partway open and snow was blowing in. He was feeling the vanity he used to feel, back in the day, and in that vanity he felt the urge to confess to Zac. He was thinking about the Pittsburgh dawn, the tannic smog scooped at the bottom of the hill with sunlight trying to get through, hitting the church. He was thinking of his wife in the chair, looking across the dining room table with the blank, winter-dark windows behind her. He was thinking about the deskman snapping a receipt into the spindle, giving him a blank look when he asked about the kid. No encephalitic deformities, no breech births or blue babies or kitchen-table caesareans in this fucking life, he thought, feeling the cold coming through the flap in his shoe. The story was his fucking story, he’d admit, wiggling his toe. Zac wouldn’t believe it if he told him. I’m Williams, he might say and get a laugh. This big reveal would make you wince, look away, feeling the same betrayal Buster felt when he thought about his former life, his wife across from him at the dining room table, holding her cup and looking at him with—he admitted to himself—a schoolmarmish, spinsterish cast to her thin, delicate features during those moments, as if she had resigned herself to the fact that long ago he had abandoned her outright, not so much to the obligations of his profession as to his fantasies of the road, doing Christ’s will on earth, nursing vagrants back to health.

You’re working too hard, she liked to say to him, widening her eyes, holding her cup with her finger extended and sipping primly and then slowly, ever so slowly, placing her cup on the saucer (a sound he could still hear) while he stared past her at the lace curtains where another Pittsburgh night descended, filling the hollows, up the hills lined with houses, and the long bulk of the Homestead Works roared and sparked not far away. Shivering, consumed with the cold, Buster could remember how it felt that morning to give in to the feeling. His own tossing in of the towel. He had only imagined poor Lockjaw’s life after he disappeared from the flophouse, as he crossed the bridge that morning, heading to that call, his bag clinking. That was the point of origin of his life now, he thought. His gut, shrunken to the size of a hickory nut, grumbled. In the rock of the boxcar over rough tracks he saw himself ease the speculum apart—his brow light catching sight of dilation that afternoon, his mind half in the task, half out, trying to imagine the whereabouts of the patient from the flophouse. The patient on his table was Mary Kearney and she was late in her term, a beauty with pale skin and a small berry-shaped mouth that seemed pursed for a kiss, and wide, deep blue eyes set in a high brow and cheekbones that caught whatever light was at hand to provide a stunning blend of delicacy and breadbasket fullness, all combined with a shame that manifested itself when she felt the cold implement and gave a single, quick wince and then uttered a sigh. He felt the cold in the flap of his shoe and the cold of the speculum. He knew he’d remember that sight forever, after the exam was over, his life, his career, his marriage. The image had to be put away where, as a profession, he placed the inherent natural desires that came from his work. He said, Fine, good, perfect, nice, everything looks good, and so on and so forth, trying in his voice to establish a light jocularity, saying, Looks like the bread is about ready to be taken out of the oven, or some other banality to ease the burden—his and his patient’s—then his vision shifted and he was delivering her baby a week later, drawing her out and leaning her in the crook of his arm the way he was trained, clearing her throat, cutting the cord while Mrs. Drake, the nurse, stepped forward and folded the drape back, covering Mary up—a stunner, he would admit later. I’m a full-blooded Pittsburgh man, he told himself. Take this to the autoclave, he heard himself say, the boxcar rattling in a buffeting wind, while behind him with a dry, starchy rustle, Mary hoisted her bloomers over her hips and patted her hair down. When he turned she presented herself with a thankful face, one that made him smile as the train roared through the Michigan night.

(Once when you were a kid you found yourself ice-skating on a pond with a young woman named Mary Kearney. It was snowing hard and the ice had to be brushed off with a broom. You worked your backward crossover and spun around her and then, suddenly, the two of you were immersed inside a sensational movement, joining mittens and spinning, falling and laughing, and she turned her face up to you—in the feeble darkness, barely visible—and for a moment you felt a flash of what seemed to be love, at least to your teenage brain, and you filed that moment and told yourself not to forget it, so you didn’t. She was in her white cable-knit sweater, her red cheeks dabbled with melted snowdrops, her mouth several years older and beyond reach. You knew that she’d be forever in your memory as a point of love, twisted in with the feeling of the blades on the ice and the sudden quiet as you fell down together and looked up into the falling snow and heard the shush of wind through the pines on the edge of the pond.)

At some point you’d let Buster speak, inspired to put his vision into a confession, to bring his memory into the boxcar, and you’d watch Zac blink himself awake, standing up to brush the hay off his legs, going to the boxcar door and looking out into the strange milky darkness of snowfall. Then you’d listen as he said, simply, Williams, Jesus, that makes sense. A man who speaks the way you speak.

They began to move because you let them. Heading toward the twist, the big reveal. (The city down the river right now is in a lockdown and yet the trains are still running. You can hear the Metro-North train horn in Croton across the water and the low hum of the engine too. As a boy you could hear the sound of the switcher train down in the mill yard, shunting boxcars of paper around and, at other times, on tracks to the west, over the hill, the Chicago train arriving into town, its horn trailing as it warned of various grade crossings—one at Stadium Drive, another at Clark Street, coming into town near your grandfather’s house.)

The sky began to shed a feeble, dry snow into the wind. Buster’s shoe had a leather flap where the stitching was worn and he had to stop to shake the snow out. Zac was talking about the future again, about his uncle who was, he admitted, a little fruity. The prize fight—the sparring session—was gone from his mind, replaced by the thirst he was feeling and the rumble in his gut. He spread his arms out and marched ahead. Buster fell behind. Buster jogged and caught up and then fell back again. Finally they reached the turnoff switch to the north and straight on to the east—and waded back into the weeds to crouch, to wait for a slow one, watching the switch signal, staying low in the blowing wind, not saying a word, until there was a glint of a headlight and the sound of a coming train—in this moment they were deep in routine, perfectly still. Here she comes, Buster finally said. His voice was husky and soft. He stood up and moved to the tracks and Zac followed him in a doggish manner. Far off, hidden in the snowfall, a train was coming, giving them both an immediate sense of anticipation and destiny as they crouched down studying its approach, waiting for the moment—because the train was moving slowly on account of the switch—that would allow them to study their options, to locate the exact right place to leap, an open doorway with some other fellows reaching down to help, or an empty one that looked particularly enticing. And then the train would do all the work to get them up there, to release you from the burden of making it all up, and you’d watch, and listen, sending your love to them through time, memory, and space so that at least for a few minutes, on the way north, they’d be alive again, holding on to each other in the corner of the car, looking out the doorway at the passing farms, the flat, soggy old winter fields, where all stories rest alone in the silence of time itself, you think, trying not to let them go, trying to find a way to get them to pause, two wayward men down in that verge, looking for the headlight that they both know will appear, submerged in snow and growing brighter by the second.