What do most of us do when we notice a hungry, disoriented person slumped on the street in obvious despair? Why, we pass quickly by, averting our eyes toward an advertisement, a stream of taxis, the window dressing in a shop. Part of the excitement of a great metropolis is how it juxtaposes: starvelings blowing on their fingers in front of Saks; urchins shilling for a three-card monte pitchman alongside a string of smoked-glass limousines; old people coughing, freezing next to a restaurant where young professionals are licking sherbet from their spoons to clear their palates.

In the eighteenth century, Tom Paine wrote that in New York City “the contrast of affluence and wretchedness is like dead and living bodies chained together.” Or as is said nowadays: Takes all kinds. Those hungry people foraging in garbage cans apparently didn’t start a Keogh plan or get themselves enrolled in some corporation’s pension program thirty years ago. They didn’t “get a degree.” So they are not maintained at the requisite room temperature society provides for the rest of us year-round; they stand in the cold wind, hat in hand, or line up forlornly in front of a convent for a baloney sandwich at 11 am.

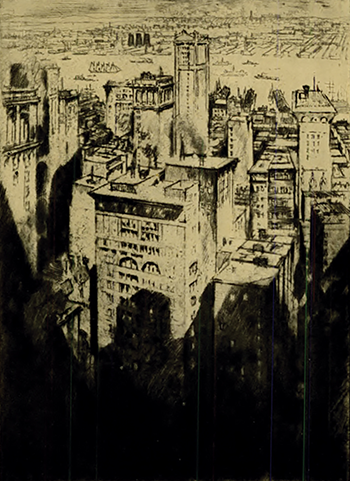

“New York is getting unlivable,” people say. An adage among the privileged is that “you can’t live in New York on less than $150,000.” But if this isn’t swinishness talking, the real meaning is that it costs that much not to be in the city—to be elevated above the grief and dolor of the streets, with sufficient doorman protection to shield you from the dangers there, to exclude anyone with a lesser income, and to conceal from you the fact that a city is its streets. A city is its museums, too, but in New York, Goya is in the streets more than in the museums.

Our ancestral wish as predators is that somebody be worse off than we are—that we see subordinates, surplus prey, or rivals hungering. This assures us we’re prospering. Rather in the same way that we dash sauces on our meat to restore a tartness approximating the taint of spoilage wild meat attains, we want a city with a certain soupcon of visible misfortune, some people garishly on the skids, scouting in the gutter for a butt and needing to be “moved on.” In a major city, in other words, there should be store detectives collaring shoplifters while we finger our credit cards, white-haired men being bullied by mid-level executives younger than they are or forced to hustle around the subway system as messengers. That quick-footed, old-eyed gentleman with the wife in a lynx coat, grabbing a cab on Sixth Avenue to go uptown after a gala, leaves behind an old Purple Heart soldier with his broken leg in a cast who may sleep on a grate tonight in the icy cold. You’re sick? You have no co-op to go to? No CDs, no mutual funds? Where’ve you been?

A city is supposed to be a little bit cruel. What’s the point of “making it” if the servants in hotels and restaurants aren’t required to act like automatons? A city with its honking traffic jams, stifling air, and brutal cliffs of glass and stone is supposed to watch you enigmatically, whether you are living on veal médaillons and poached salmon or begged coins and hot dogs. But stumble badly and it will masticate you. Sing a song and exhibit your sores on the subway and it will nickel-and-dime you as you gradually starve.

Some days the ills of the city seem miasmal and mental, a delirium of drugs and dysfunctions, a souring in the gut like dysentery. The creeds or the oratory that ought to invigorate us seem exhausted, whether derived from Marx, Freud, or capitalism (newly perverse). We New Yorkers, rushing to keep up with our calendars, pausing to open a fast-food package and finding that the plastic wrapper resists our fingers, immediately, unthinkingly, move it up to our teeth. Wild we still are, but possessed by velocities too fast to stay abreast of ourselves, strewing empathy and social responsibility behind us as we go.

From “Too Much, Too Blindly, Too Fast,” which appeared in the June 1989 issue of Harper’s Magazine.