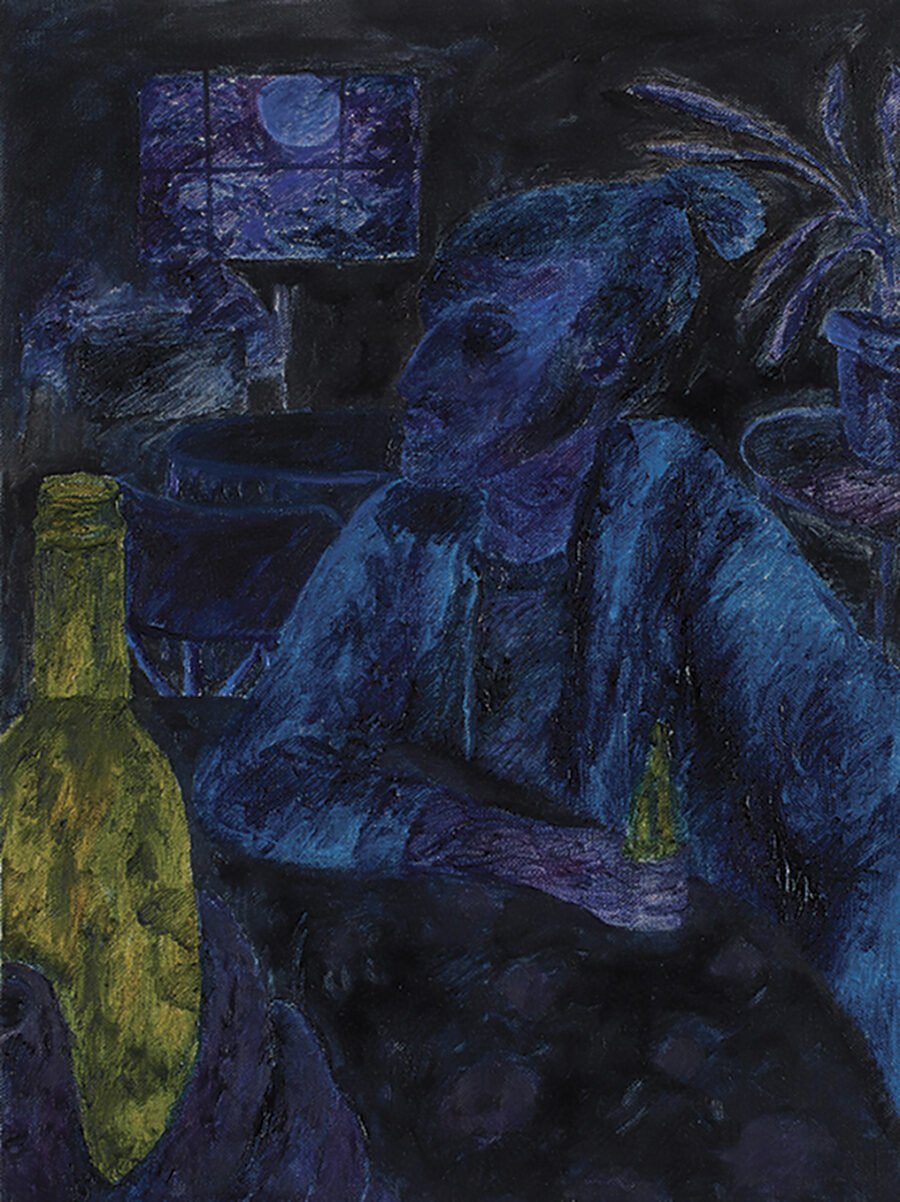

© Srijon Chowdhury. Courtesy Foxy Production, New York City

Triptych

In an effort to replenish its anemic membership with younger blood, the New Amsterdam Club has, among other measures, relaxed its dress code, allowed the use of cell phones, and added a mezcal cocktail to the menu. Yet one unspoken rule remains unchallenged: no business talk on the premises. Unless, maybe, in what’s known as “the little bar.” No one would dream of discussing work in the big bar or the dining room, but the little bar is a territory with a diplomatic status and a legislation of its own. Conversations are kept brief and drinks left unfinished out…