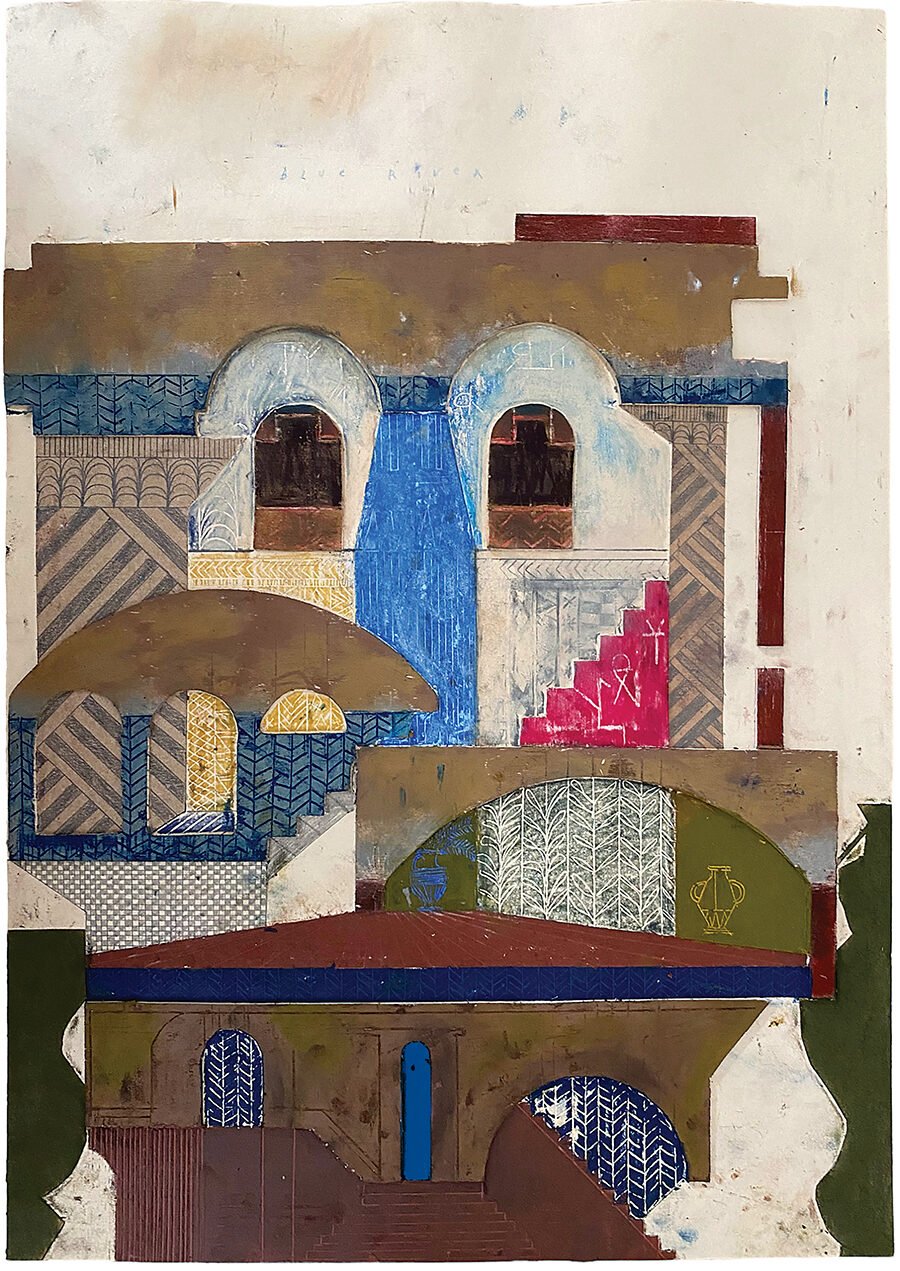

Blue River, by Abel Burger © The artist. Courtesy Brigade Gallery, Copenhagen, and private collection

The Conversion of the Jews

They lived in narrow streets and lanes obscure,

Ghetto and Judenstrass, in murk and mire;

Taught in the school of patience to endure

The life of anguish and the death of fire. . . .

Pride and humiliation hand in hand

Walked with them through the world where’er they went;

Trampled and beaten were they as the sand,

And yet unshaken as the continent.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “The Jewish Cemetery at Newport”

In the summer of 1933, while traveling in a tour bus through the Judean desert, Solomon Adelberg, twenty-four years old, disembarked,…