We were all there for Pablo Neruda, but nobody seemed to like Pablo Neruda. The members of the Chilean media had assembled on a rock formation that rose up from the beach, a formation that now bristled with tripods like a sea urchin, a dozen lenses trained on the darkened windows of Neruda’s hillside home. Nothing was happening there; the poet lay still in his grave.

“He wrote all these love poems, but he was a son of a bitch,” said a reporter from a wire service. She poured Nescafé from a thermos into a styrofoam cup and recited a brief history of the poet’s amorous cruelty. She wondered about Neruda’s first divorce, a hasty arrangement in Mexico, possibly unofficial. Was Neruda a bigamist?

“Neruda was a plagiarist,” said another reporter. He picked the ham out of a ham sandwich, tossed the meat to a stray dog, and ate the bread. The reporter was a vegetarian. He cited the verse from “Poem 16” of Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair that Neruda lifted almost verbatim from the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. This had generated some controversy in the 1930s. The reporter said that we should not be bothering with Neruda at all; the real story was the recent opening, down the coast, of a museum to honor another Chilean poet, Vicente Huidobro.

A more reverential scene played out on the beach underneath the rock. Youth representatives of the Provincial Orchestra of San Antonio had gathered below Neruda’s house to perform classical standards and Chilean folk songs. Candles flickered before a small shrine draped with the national flag. Tourists photographed a folklorist wearing a caftan. Dignitaries of the Communist Party wandered around, offering commentary for the video cameras. The boss of a local fishermen’s union recited Neruda’s “Ode to Conger-Eel Broth.”

On the hillside by the house, Neruda’s tomb had been shielded from view by a white sheet. The press attempted to circumvent this primitive barrier — climbing the fence, aiming telephoto lenses from the balconies of the home next door, deploying an insectoid remote-controlled camera helicopter that hovered in the sky.

At nine-fifteen in the morning, the orchestra put their instruments in their cases. Up at the tomb, Neruda’s family, along with several political eminences, filed behind the white sheet for a brief ceremony. For twenty minutes, all was quiet. By putting my eye to a hole in the fence and peering upward at a gap in the curtain, I could see workers in white lab coats, gas masks, gloves, and surgical caps. For the third time in forty years, Pablo Neruda was being unearthed.

In 1962 the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra described the work of his friend and rival Pablo Neruda with the following formulation:

In general terms we could say that the process of development of our poet consists of:

I. A fall from the leaning tower of consciousness to the abyss of the chaotic and nebulous subconscious.

II. A somewhat extended stay in that asphyxiating atmosphere.

III. A triumphant return to reality after a bloody fight.

He repeated this assessment in further terms:

Neruda’s evolution is also susceptible to the following equivalent formulation:

Conflict, Rupture, Reconciliation

Dusk, Night, Dawn

Clash, Retreat, Victorious Advance

Autumn, Winter, Spring-Summer

Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis.

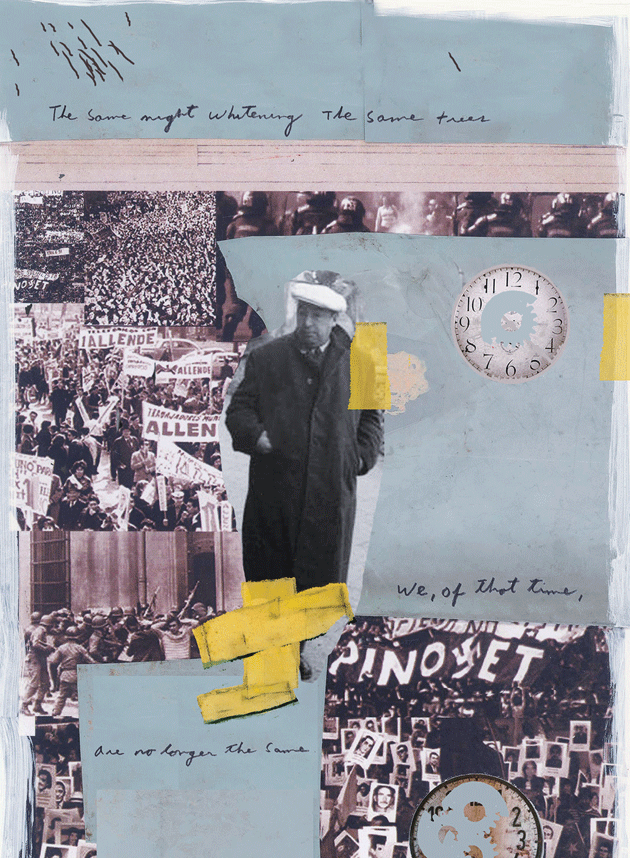

Parra was talking about Neruda’s poetry. A half-century later, the formulation also applies to the passage of Neruda’s corpse through space and time. One dialectic maps very neatly onto the other: the three burials of Pablo Neruda; the conflict, rupture, and reconciliation of Chile; the dusk, night, and dawn of the Chilean left. In September 1973, in the turbulent aftermath of the military coup that initiated the long dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, Neruda died and was hastily interred in the borrowed mausoleum of a family friend. In 1974, as Pinochet consolidated power, Neruda’s remains were moved to an unexceptional niche tomb in another part of Santiago’s General Cemetery, where they stayed for the duration of the long dictatorship. In 1992, four years after the referendum that signaled the end of Pinochet’s presidency, the poet finally received the burial he’d wished for, facing the sea at his home in Isla Negra.

Until 2013, the uncanny coincidence in the timing of Neruda’s death and the beginning of Pinochet’s dictatorship produced a sentimental canard: although the poet officially died of prostate cancer twelve days after the coup, it became common in Chile to lament, with a sigh, that the Communist poet had died of “a broken heart.” The explanation sufficed for almost forty years. Then, in 2011, Neruda’s former chauffeur alleged that the poet had not died of prostate cancer, or of a broken heart, but had been poisoned in the early days of the coup by an agent of Pinochet’s regime in Santiago’s Santa Maria medical clinic. Once again, the poet’s surviving relatives donned their dark suits, the leadership of Chile’s Communist Party prepared statements, and the television satellite trucks convened.

Neruda wrote his most famous book as a teenager, and it’s a book about teenage love. Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair, one of the best-selling books of poetry in Spanish of all time, was published in 1924, when Neruda was not yet twenty years old. He had recently escaped to Santiago after a childhood of mud, zinc roofs, damp shoes, and earthquakes in southern Chile. “The rain was the one unforgettable presence for me then,” he later wrote of his childhood.

As a boy, Neruda was known for his gloomy disposition and gaunt figure. His friends called him Shinbone. In Santiago, in emulation of Baudelaire and Rimbaud, he lived in shabby boardinghouses and saturated himself with red wine. If he was courting the tubercular fate of many residents of Santiago in the 1920s, and young poets everywhere, his biographers contend that he only avoided it by a miracle. He wandered the city streets in a black cape and a wide-brimmed hat, befriending anarchists and writing poems every day. His first book, Crepusculario, was published by an anarchist student association; his second, Twenty Love Poems, by Nascimento, one of the country’s most prestigious publishers.

Neruda may have been mimicking Europeans in his lifestyle, but his poetry, with its surrealist transposition of southern Chile’s volcanic landscape onto the bodies of his lovers, belonged unmistakably to twentieth-century America, and was unlike anything that preceded it in Spanish-language literature. Twenty Love Poems centered on two fellow teenagers: a country girl, whom Neruda nicknamed Marisol (sea and sun), and a city girl, whom he called Marisombra (sea and shadow). The first was later identified as Teresa Vasquez, a friend from Neruda’s adolescent summers in a seaside town. The second was Albertina Rosa Azócar, whom Neruda met when he was eighteen, she was sixteen, and both were students at the pedagogical institute in Santiago. A photo of Azócar at the time shows a grim, dark-eyed girl with a bow atop her head, like a pile of rocks into which a half-deflated zeppelin has crashed. Thanks to Neruda, history will remember her otherwise: “Body of skin, of moss, of eager and firm milk. / Oh the goblets of the breast! Oh the eyes of absence!” Chileans remain fond of Twenty Love Poems, but they temper their references to it with irony. “I like you when you are silent because it’s as if you are absent,” a young man might quote to his sweetheart, from “Poem 15.” Then they will laugh.

Neruda followed Twenty Love Poems with Endeavor of the Infinite Man, which is notable for the poet’s rejection of all punctuation marks. His promise to make up for it with a book consisting entirely of punctuation marks was never fulfilled. Instead, in 1933, when he was twenty-nine, he published Residence on Earth, the collection often considered his greatest. He wrote most of it while working as a consular officer in Asia, during a lonely five years that he spent rereading Proust, Schopenhauer, and Rimbaud. He still wrote love poems, mostly about a local woman he met in Rangoon. He referred to her by the pseudonym Josie Bliss, and her real name remains unknown. She loved Neruda obsessively; he memorialized the sound of her peeing behind the house. In 1929, he left her for a new job in Colombo, where his closest companions were a mongoose named Kiria and a manservant named Bhrampy. Neruda begged Azócar to come to Asia and marry him. She did not respond to his letters.

Neruda’s desolation widened his poetic repertoire. His interests shifted to the ticking clocks, shopwindows, and consumer goods that cluttered the life of the modern city dweller. “There is too much furniture and there are too many rooms in / the world / and my body lives downcast among and beneath so many things,” he wrote in “Ritual of my Legs.” A list of favorite objects emerges in Neruda’s poetry from this time — shoes, doves, ashes, teardrops, suits, stockings, and clocks. Collectively the objects evoke the adjustment to a century of stamps, trains, and desks. “Walking Around,” Neruda’s homage to James Joyce, and one of his most beloved poems, describes the simple weariness of being alive in a city:

All I ask is a little vacation from things: from boulders and woolens,

from gardens, institutional projects, merchandise,

eyeglasses, elevators—I’d rather not look at them.

Neruda’s poetry underwent another shift in the 1930s, when he accepted a diplomatic post in Spain. His literary work expanded in coincidence with two developments: the first was the initiation of his love affair with Delia del Carril, an Argentine painter twenty years his senior whom he nicknamed La Hormiguita (the little ant). Carril was lively, sophisticated, and a Communist, and Neruda began to embrace many of her ideas. To marry her, he abandoned his first wife, a Dutch woman he had wed in Indonesia, and their disabled infant daughter, initiating a reputation for infidelity that would continue for the rest of his life. (“Poem 20”: “Love is short, and forgetting so long.”) Perhaps the greatest proof of Neruda’s paltry feelings for his first wife is that she is never mentioned in any of his several hundred love poems; as for his daughter, who suffered from hydrocephaly and died in an institution in the Netherlands while still a child, Neruda once referred to her in a letter as “a kind of semicolon, a three-kilo vampire.”

The second influence on Neruda’s politics was his close friendship with Federico García Lorca, and García Lorca’s assassination by supporters of Francisco Franco in 1936. Neruda eventually recounted his horror at the rise of fascism in Spain in Residence on Earth, which grew to multiple volumes in subsequent reprintings. In the poem “I Explain a Few Things” Neruda explains his transition from the lyrical to the heavy-handed:

You will ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak to us of dreams, of leaves

of the great volcanoes of his native

land?Come and see the blood in the streets,

come and see

the blood in the streets,

come and see the blood

in the streets!

Neruda’s experience in Spain also catalyzed his career as a politician. In 1939, the president of Chile dispatched him to organize a refugee convoy of 2,000 Spaniards fleeing Franco. After his return to Chile, Neruda became a member of the Communist Party and was elected to the Senate in 1945. His political conversion also occasioned his first exile when, in 1948, Chile outlawed the Communist Party. Neruda fled to Argentina through the Andes and then spent several years in Europe, a time memorialized in the Italian movie Il Postino (1994), which has helped establish Neruda’s other legacy, as a somewhat insipid figure of charm and whimsy.

Neruda’s personal experiences had always informed his poetry, and now, increasingly, he incorporated the jargon of political propaganda, a Marxist view of history, Stalinism, evocations of “common people,” and an idea of pan-American identity. These ideas would reach their poetic apex in his third great book, Canto General, a verse history of Latin America, published in 1950. It was this phase, according to Parra, when Neruda passed from the “self-centered absorption” of Residence on Earth to “the phase of recovery through the Marxist method.”

“To some ‘demanding readers’ the Canto General is an uneven effort,” Parra said. “The Andes are also an uneven work of art.” The book cemented Neruda’s reputation as the poetic voice of Latin American revolutionary thought: Che Guevara had a copy of Canto General among his possessions when he was killed in Bolivia.

Still, Neruda’s participation in the social struggle was always more symbolic than lived. Toward the end of his life, he became a sort of fanciful Bacchus of the left. He left Carril for Matilde Urrutia, who, following a long affair, became his third wife. (A devastated Carril left Chile.) In 1969, he ran for president until the Communist Party allied with the rest of the Chilean left to back Allende. Neruda won the Nobel Prize in 1971, while on assignment as Allende’s ambassador to France, though he eventually returned home to help shore up the president’s collapsing authority. Of his later poetry, it is his less political works, Elemental Odes and One Hundred Love Sonnets, that have stood the test of time, rather than, say, “Ode to Stalin.” His last book of poems, Call for the Destruction of Nixon, is generally considered his worst.

On September 11, 1973, Neruda was at home at Isla Negra with Urrutia. Before dawn that morning, the Chilean armed forces converged from the northern and southern reaches of the country to attack La Moneda, the presidential palace. By midafternoon, La Moneda was in flames and Allende was dead. Neruda was sick in bed with prostate cancer when he heard the news, but he was still lucid enough to dictate his thoughts on the upheaval for the final chapter of his memoir. “That body was buried secretly, in an inconspicuous spot,” he wrote of Allende. “That glorious dead figure was riddled and ripped to pieces by the machine guns of Chile’s soldiers, who had betrayed Chile once more.” In fact, Allende had died from a single, self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. From the very beginning, in other words, the exact version of what had happened was muddled.

The human rights abuses under Augusto Pinochet are by now well documented: more than 30,000 Chileans imprisoned and tortured; some 3,000 killed by members of the military junta. It is not paranoid to suppose that the junta contemplated the murder of Neruda; the razing of Chilean culture began with targeted murders, and the haste with which the junta dispatched cultural figures speaks to the threat they represented to the right wing. Victor Jara, the Communist folk musician and theater director, was imprisoned in the National Stadium the day after the coup and executed four days later, after extensive torture. Media outlets not supportive of the coup were shut down. In the universities, dissident professors were fired. The Communist Party was again outlawed. Book publishers had to submit manuscripts to a government censor.

Neruda died before most of this happened. Compared with the 70,000 people who had celebrated the poet’s Nobel Prize in the National Stadium two years earlier, attendance at Neruda’s funeral was sparse. The city was under curfew. Thousands of leftists had already fled the country. The people with whom Neruda had most often associated — the political and literary elite of Chile, including President Allende himself — were absent, dead, or in hiding. His cortege consisted of scattered ambassadors, who had diplomatic immunity, and young people who perhaps did not yet fully grasp what was going on.

To watch the fragmented footage of the funeral, which today plays on a loop in Santiago’s Museum of Memory, is to witness a mourning that goes far deeper than the death of a single literary figure. The attendees look stunned. At first they walk in silence, following the coffin past heavily armed police officers, seeming unsure whether they will be stopped. A young woman weeps and faints into her friend’s arms. As they approach the site of the tomb, their silence breaks. They sing “The Internationale.” They chant revolutionary slogans. They recite Neruda’s poems, their voices cracking. A group of young men is shown with tears rolling down their cheeks. Neruda’s funeral is generally considered the first public demonstration against the right-wing dictatorship. For many years, it would also be the last.

I first visited Pablo Neruda’s houses when I was seventeen, in 1998, the year I was an exchange student in the seaside city of Viña del Mar. The Chile I knew then was a different place from the country I recently returned to. At the start of 1998, Pinochet was still commander in chief of the army, though later that year he retired to assume a position as “senator for life.” He also claimed legal immunity from prosecution for human rights violations, despite lawsuits that had increased in number as the 1990s progressed. In a profile of Pinochet written at the time, The New Yorker’s Jon Lee Anderson referred to him as “that rarest of creatures, a successful former dictator,” citing both his continued popularity among a significant portion of Chileans and the power he continued to wield in government. But 1998, it turned out, was the year when all that changed: Pinochet was arrested for the first time, in London, under the order of Spanish judges prosecuting crimes committed against Spaniards in Chile during Pinochet’s regime.

My understanding of these happenings was limited: the family I lived with was conservative and supported Pinochet. Despite irrefutable evidence of the regime’s atrocities, their view remained a socially acceptable opinion. My own impulse toward moral condemnation was complicated by the affection and gratitude I felt for them. The argument of the parents was that Pinochet had rescued the country from the chaos and violence of a potential civil war. The father, a marine navigator who had once supported Allende, gave the common defense of Pinochet (one given in the pages of the Wall Street Journal as recently as 2013): in this view, the torture and killing were simply byproducts of the imperative for free-market reform and the restoration of national stability.

The discomfort around the subject extended to the tiny Catholic school I attended, where politics were not discussed. The curriculum focused on the memorization of dates and events, not the interpretation of causes and effects. The conservatism was total. Every Monday before class, we lined up in the concrete schoolyard by grade, in our uniforms — if you were a girl, a blazer and tie worn with a belted pleated jumper and gray knee socks. A scratchy recording played over a loudspeaker, and we sang the national anthem before filing solemnly into our classrooms, where we hung our blazers on hooks and put white lab coats over our uniforms. Divorce and sodomy were illegal at the time, and one felt the stigma and shame of those who did not conform to the neatly ironed vision of the Catholic family that had been upheld by the military regime. My classmates were uninterested in talking about Pinochet. Most people argued that what had happened was in the past and not worth discussion. I never heard the daughter of my host family, who was twenty years old then, and who came out as gay nine years later, express any opinion about Pinochet. We were good friends, but in accordance with the prevailing spirit of the place and time, I was too polite to ask her about politics. In school I saw no recounting of human rights abuses, no declaration among the students of any political affiliation, no heated expression of political passion. At the time, I found this difficult to understand. Now I have a better understanding of their insularity: they were children of the 1980s, and in the 1980s, Chile’s cultural life was defined by nationally televised events.

A Chilean of a certain age can list these events the way they can list the country’s worst earthquakes: the coverage around the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1986, the visit of the pope in 1987, the Rod Stewart concert in 1989, the annual telethon fund-raiser for disabled children. The telethon, like the Super Bowl, was much anticipated and universally watched. “You’re going to cry so much,” my friends promised at school. The household schedule, too, was organized around television: we watched the dubbed Globo telenovela from Brazil while I ate lunch after school; the patriotism-inflected news in the evening (including a weather forecast for the slice of Antarctica, population 115, that Pinochet had named a Chilean province in 1975); and then the Chilean telenovelas during once, evening tea and sandwiches. One could watch the news every night and read the papers every morning yet still avoid hearing stories of conflict over what had happened in the country’s very recent past, or vocal opposition to the general presentation of history. As I grew older this experience served as an important reference point for what it feels like to mistake censorship for consensus, and of the perils of a neutral stance.

Neruda’s houses offered proof that another Chile had existed and probably still existed somewhere, one that did not listen to multinational pop music or confine cultural discussion to the changeling plot of Globo’s Por Amor or Canal 13’s Amándote. I first visited La Sebastiana, Neruda’s house in Valparaíso, with the mother of a classmate, who later took me to Isla Negra too, and to a former bohemian enclave near the sea called Horcón. (I wrote in my diary that the town was dismissed by the family I lived with as a nest of drug addicts.) My friend’s mother was an art student in the south of Chile at the time of the coup, and she was briefly detained, along with her brother, at the start of the dictatorship. Now she was a single mother who worked at Falabella, a department store. To visit Neruda’s houses with her was to revisit (or at least I thought of it this way, maybe I was romanticizing) her youth, which had not just faded into memory but had been utterly destroyed.

Neruda treated his houses as museums even while he lived in them and assigned little stories to each of the objects inside. The tours focused on his collections of glass bottles, ship figureheads, and shells, and on his many love affairs, more than they did on his politics, but even this fairy-tale memory of Neruda affirmed a way of being Chilean that had nothing to do with the flags and the marches, the medals and the pomp, the neatly dressed children running to embrace the pope.

In the fifteen years since I left, Chile has undertaken a powerful revision of its history. Museums documenting the abuses committed by the military junta have opened, including Londres 38 in 2008, at the site of a notorious torture center in downtown Santiago, and the Museum of Memory in 2010. Filmmakers have released documentaries about former concentration camps and the fate of the disappeared. Santiago has even changed the names of streets — in 2013, September 11 Avenue reverted to its old name of New Providence. Younger writers like Alejandro Zambra, who was born in 1975, and filmmakers like Pablo Larraín have focused their work on the 1970s and 1980s, when Chile’s “inxiles” — as writers who remained in the country during the dictatorship sometimes refer to themselves — were prevented from openly depicting the oppression of the junta in their work. (“To want democracy was to not talk about the past,” Zambra explained to me, during a visit to the Museum of Memory. “We felt we had to erase it.” For those who experienced brutality, what had happened was often too traumatic to revisit. For those who had not, he said, the experience of Chile in the 1970s and 1980s was considered banal and sheltered, undeserving of recollection.)

Then there are the bodies. Since the official end of the military dictatorship, in 1990, there have been a lot of moving bodies. Salvador Allende’s remains were taken from an understated plot in Viña del Mar and given a proper monument in Santiago’s General Cemetery. The remains of Orlando Letelier, the leftist foreign minister under Allende who was assassinated by agents of the Chilean secret police in Washington, were taken to Santiago from Venezuela, where he had been buried.

Pinochet’s death, in 2006, initiated another era for the beleaguered corpses of the Chilean left: the era of forensic examination. Allende was exhumed in 2011; his death was officially determined to be a suicide. Victor Jara was also exhumed: he had died of forty-three bullet wounds — after a lieutenant in the Chilean army shot him in the head during a version of Russian roulette. Neruda was returned to Isla Negra. For those who remained buried, the government began inquiries, including into the circumstances of the death of President Michelle Bachelet’s father, who was tortured to death by the regime in 1974. Finally, there was Neruda.

Manuel Araya is a tall man, with a somber demeanor and a bald head fringed by salt-and-pepper hair. He does not crack jokes or smile unnecessarily. He speaks with a rapid intensity, telling his story with little dramatic embellishment, as if pressing play on a worn cassette tape in his mind. Today he is in his mid-sixties, still a member of the Communist Party, and still living in the town of San Antonio, down the coast from Neruda’s home in Isla Negra. On April 7, 2013, as the Chilean government’s legal-medicine service prepared Neruda’s tomb for the exhumation, Araya spent most of the day standing on the beach below Neruda’s house, dressed in a gray pinstripe suit and tie, tirelessly repeating his story, obeying the dictates of cameramen who had him walk pensively along the sand, stare out at the sea, or gaze thoughtfully at the knotty, windblown pine trees that surround Neruda’s home.

Araya was a fourteen-year-old Communist activist from San Antonio when he first met Neruda. In November 1972, when Araya was twenty-five, Neruda hired him as his chauffeur, personal assistant, and bodyguard. Neruda was already ill with prostate cancer, phlebitis, and a host of other ailments, but Araya claimed that the poet was not yet on his deathbed. Now, speaking to the cameras, Araya described a mysterious occurrence in the clinic on the day before the poet’s death: a doctor entered Neruda’s room while he was sleeping and administered an injection in his stomach, which was followed by a rapid deterioration of the poet’s health. Araya had not been present at this event — he and Urrutia had gone back to Isla Negra to collect some books. Neruda called and told them to quickly return. Araya and Urrutia sped back to Santiago, where they found the poet florid and in pain, a sudden shift in his condition. “I said to him, ‘Don Pablo, what’s happened to you?’ And he told me, ‘A doctor gave me an injection.’ He said, ‘Manuel, I’m burning up inside.’ ”

Fifteen minutes later, after he’d been dispatched on an errand, Araya was pulled over by the police and taken to the local station. He was beaten and interrogated about his Communist contacts, then taken to the National Stadium, which had become a notorious site of torture and death. When Neruda died, at around 10:30 p.m. on September 23, 1973, his chauffeur was still imprisoned there. Two months later, thanks in part to efforts by Neruda’s friends, he was finally released.

“Officials would later report that he was tough and would not divulge a word,” Urrutia wrote in her memoirs. “This poor man, who had traipsed around with Pablo to flea markets and antique shops — what were they really going to learn from him?”

Araya first published his allegations in the San Antonio Leader, the newspaper of his hometown, in 2004, two years before Pinochet’s death. Nobody paid any attention. In 2011, one of Araya’s Communist colleagues contacted the Chilean correspondent for Proceso, a Mexican newsmagazine. The resulting article ignited a firestorm of media attention across Latin America and prompted Chile’s Communist Party to file a criminal lawsuit for an official investigation. Neruda’s family expressed support for the inquiry, calling it a “moral right,” although the foundation that manages Neruda’s houses and literary estate opposed it. (In response, some accused the foundation of trying to sanitize Neruda’s political record, to reduce the poet to his wine-drinking, dinner-party-hosting fanciful caricature.) Mario Carroza, the judge who presided over Allende’s exhumation, determined that Araya’s story supplied legitimate cause for a forensic investigation.

There was certainly a motive for murder — had Neruda lived and gone into exile, he would have been the nexus of an opposition. Following his death, troops ransacked and vandalized his houses in Santiago and Valparaíso. In the years that followed the coup, other members of Neruda’s inner circle were tortured and murdered, including Homero Arce, his personal secretary and a friend of more than fifty years. (Arce was fatally beaten, and his corpse was deposited for his wife on their doorstep.) Araya’s older brother, Patricio, disappeared the same year; Araya believes he was murdered in a case of mistaken identity. Nearly ten years after Neruda’s death, former president Eduardo Frei died unexpectedly in the same clinic, while being treated by the same doctors, in a confirmed case of poisoning.

There is ample documentation to prove that the Pinochet regime experimented with poison, and Neruda’s treatment was shrouded in mystery: Neruda’s doctor, Sergio Draper, denied murdering his patient, but he did describe to investigators the presence of an unknown doctor by the name of Price, who seems to have never existed in any official record. The Chilean press quickly tied Price to an American named Michael Townley, whom some suspected of being a CIA agent, but a convincing paper trail showed that Townley was in Florida at the time, and the trail ran cold. Only the corpse was left. A panel of international forensic experts was assembled, plans to unearth Neruda’s body were made, and here we all were on the beach to watch the show.

Pinochet still enjoys a privileged status among Latin American dictators. He died never having been convicted of a crime, and Chileans can still proclaim “Viva Pinochet” without fear of total ostracism. Nevertheless, his influence has greatly declined. The revelation, in 2004, that he had stolen money from government coffers allowed even the most stubborn Pinochetista to disavow him without handing a victory to the “terrorists.”

In the company of a friend, I paid a visit to the museum the Pinochet Foundation maintains in Santiago, in the neighborhood of Vitacura. The museum is located in the house from which Pinochet ran his affairs in his final years, and its homage to the dictator hides behind a banal façade. Visits can be made by appointment only, and from the outside the house is unmarked. Our guide was Carolina Rojas, aged twenty-seven, a lovely young woman in a green cardigan and cheery marigold-yellow scarf who showed us the artifacts inside. The museum perversely mimicked the national museum that honors the victims of the regime: there was a Wall of Victims with gold plaques marking the names of police and military officers who died fighting the “terrorists.” (“Many people don’t know that there were five terrorist groups active in Chile,” Rojas said.) There were Pinochet’s medals from his visits abroad, and the dining room table where he held his meetings while under house arrest in London. There were photos of Pinochet smiling with nuns, with small children, and while touring Antarctica. There were his statues of Napoleon, his desk with its framed photos of his mother and his wife, the ornately carved throne where he sat to watch TV. There was his small, antiquated TV. My friend, who was more combative than I was, asked Rojas how she could justify working here, given the evidence that at least 30,000 people were tortured under Pinochet. Like many Chileans of her persuasion, and despite her youth, Rojas cited the economic progress the country made under the dictator. She mentioned the Southern Highway, the telephone system, the airports, and primary education. Under Allende, she said, her grandmother had to wait three hours to buy a kilo of bread. After the tour, she gave us books with such titles as Chile Chooses Liberty, Augusto Pinochet: A Soldier of Peace, and Augusto Pinochet: The Rebuilder of Chile. Photos were available on the museum’s Facebook page, she said. She laughed as she recalled having to explain Facebook to the people who run the foundation, but was pleased to tell us that the Pinochet Foundation now had 3,000 page likes. Pinochet, who was cremated, has no public tomb. His ashes are stored away from public view, in an urn, in the chapel of his old summer retreat in Los Boldes.

The most thorough rejection of Pinochet has come from those who were born after the end of his dictatorship. Since 2011, tens of thousands of Chilean students have taken to the streets to protest the dictator’s legacy of privatized education, paid for with high-interest student loans. Three days after Neruda’s exhumation, I borrowed a gas mask from a friend and went to watch the students march in what was said to be the biggest street protest since the 1980s, with an estimated 80,000 people participating. The students marched peacefully, filling both sides of the wide Bernardo O’Higgins Avenue. They carried banners representing their courses of study (the earth moves — engineers too!) or condemning the powers that be (michelle, i don’t believe you anymore!; after reaching her term limit in 2010 and taking a break from politics, Michelle Bachelet won the presidency again in 2013). Few of the participants appeared to be older than twenty-five, and most of them were still teenagers. Many seemed charmingly in the throes of true love, holding hands and making out during pauses in the march.

At the protest’s terminus, the students gathered around a papier-mâché effigy of Lady Justice in flames. I found myself standing next to a twenty-year-old student named Sergio who was studying psychology at the University of Santo Tomás. He wore tights, satin breeches, an ascot, and a powdered wig, and held a fistful of painted cardboard dollars. His snow-white stockings were marred with paint pellets from an encounter with the police. I asked what his costume was about. “I personify a bourgeois,” he announced with a slight bow, “because education in Chile is dominated by the bourgeoisie.” Santo Tomás, a private university, is one of the most expensive in the country, he said, one that students like him go into debt to attend, but the money goes to profit rather than to a better education. As we spoke, the police began the long process of breaking up the march, a ritual that involved herding everyone into side streets with tear gas and armored tanks that shot high-powered jets of water. When we all began to sneeze, those of us with gas masks put them on. I stood under an eave on a side street wearing my mask and watching as the stragglers tried to topple a traffic light and threw rocks at the police. Next to me, a young man spray-painted rebel students subversive and of the people on the wall. The stray dogs that are everywhere in Chile’s streets trotted behind the armored water cannons, lapping up the water in their wake, while the students scattered before the blasting jets.

In the middle of the march, I had briefly stopped for an interview at La Chascona, Neruda’s house in Santiago, which was a few blocks away from where the protest convened. The landscaped grounds of the house were silent, in contrast with the vigor and excitement in the streets. The gift shop, with its Pablo Neruda mugs, felt . . . bourgeois. Still, despite his staid and avuncular place in national memory, Neruda’s socialist ideals live on in these protesters. After being constitutionally banned for two decades, his Communist Party is beginning to reinvent itself for a different age. While I attended the protest, leaders of the student movement, such as Giorgio Jackson and Camila Vallejo, were busy campaigning for Congress. Of the four graduates of the student movement who assumed congressional positions in 2014, two are members of the Communist Youth of Chile party, and all are in their mid-twenties. The photogenic new generation of politicians has near-celebrity status: the news that the twenty-five-year-old Vallejo was pregnant made the front page of national papers while I was in town, with headlines blaring mamita.

But the break between this generation of activists and the people who grew up under the dictatorship is so vast that it almost defies understanding. Even the most committed of Chile’s aged leftists cannot quite believe the boldness of the country’s youth. On the night of the protests, CNN interviewed an elderly woman who had been captured by news cameras trying to dissuade anarchist youths from destroying a traffic light. The woman, Monica Araya (no relation to Manuel), was not a conservative or a tut-tutting conformist but a well-known lawyer. She had lost both her parents and a son to the dictatorship, and had suffered through detention herself. She emphasized that she supported the students’ push for free education — she participates in their marches and goes to the police station to get them out of jail afterward — but she saw the renewed possibility of violent repression in their careless destruction. “I don’t want violence again,” she said repeatedly.

In May 2013, a month after my visit, the head of the forensic team in charge of Neruda’s exhumation, Patricio Bustos, who when I met him had intoned “Poem 20” from memory, announced that the experts had confirmed the presence of metastatic cancer through an analysis of Neruda’s bones. In November, the final verdict came in: the doctors had found the presence of chemicals used to treat cancer at the time, but no toxic substances.

For Manuel Araya and his allies in the Communist Party, the verdict left room for doubt. Neruda’s nephew wondered about the possibility of biological agents. Carroza, the judge, agreed that further tests might determine the possible presence of thallium or sarin. But for most observers, the story was over: Neruda had died of natural causes, of prostate cancer.

Still, no matter what the results, each exhumation represents a restoration to prominence of a cultural figure who had been struck from the record. Each serves a symbolic function as well: a solved mystery for the many Chileans whose murders from that era remain unsolved. The night of the protests, as I watched Monica Araya on television, she spoke of her struggle to learn the fate of her family members. She still does not know how her parents died. “If I wanted to visit the bodies, to leave a flower for my mother or my father, I don’t have a place to go,” she said. “All of us have the need for a designated place to go leave a flower.”

Neruda’s grave at Isla Negra overlooks a scene of unceasing motion, the waves crashing against the rocks, the wind twisting the pine trees shoreward. The basalt headstone, carved with his name and Urrutia’s, reduces Neruda’s complicated love life to a vision of unlikely marital eternity. In Canto General, Neruda had asked to be buried here, but he would not have seen his unearthing as a desecration. He had, even then, foreseen the inquietude:

Let the gravediggers pry into ominous

matter: let them raise

the lightless fragments of ash,

and let them speak the maggot’s language.

I’m facing nothing but seeds,

radiant growth and sweetness.