“If we want to know what American normality is — i.e. what Americans want to regard as normal — we can trust television,” David Foster Wallace once wrote. Can we? It’s a chicken-or-egg situation. Does television teach us what’s normal? Or does it only absorb new social realities after a quorum of Americans has gotten on board? Certainly a number of recent shows have taken it upon themselves to educate and enlighten their audiences, with story lines about everyday sexism (Master of None), racial profiling (The Carmichael Show), and the experience of undocumented immigrants (Jane the Virgin). These moral tales tend to be gentle and earnest, like the little allegories about diversity that used to run on Sesame Street. Then there’s the Amazon show TRANSPARENT, in which Ali Pfefferman (Gaby Hoffmann) recites a poem by Eileen Myles at a lesbian bowling night:

I always put my pussy

in the middle of trees

like a waterfall

like a doorway to God

like a flock of birds.

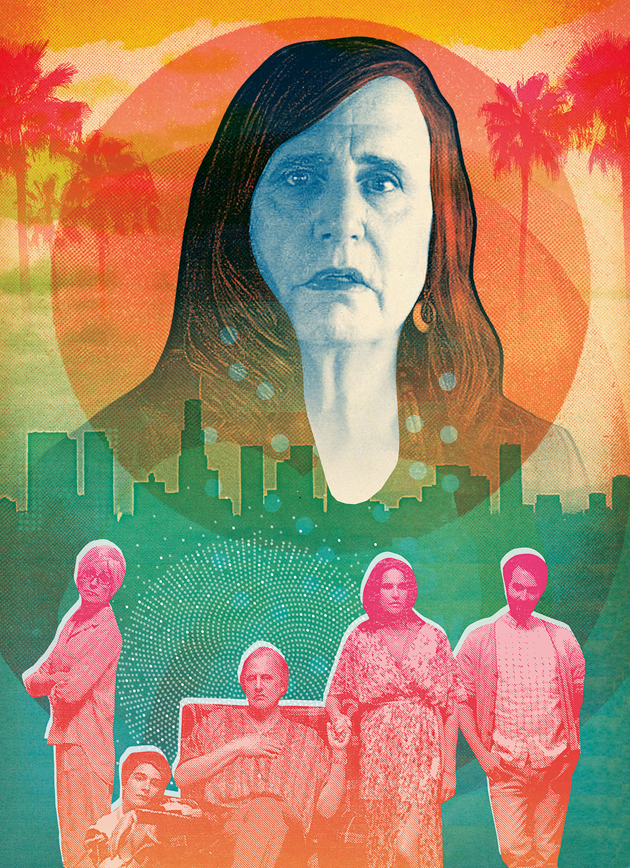

The title of Transparent is a pun. The show is about a transgender woman in her late sixties named Maura Pfefferman (Jeffrey Tambor), who lived for most of her life as a man named Mort. Under this name, Maura married and had three children, whom she raised in Pacific Palisades, in Los Angeles. She had a public career as an academic and a private collection of silk kaftans. At the beginning of the first season, Maura, now divorced and retired, wanders the vacant corridors of her memory-laden house in the drapery that makes her feel free. When the time finally arrives to break the news to her family, she summons her three thirtysomething children home, like King Lear, but her nerve fails her. She watches glumly as her progeny squabble and gnaw on take-out barbecue, oblivious to her turmoil. “I made a commitment here last week that I was going to come out to my kids and I didn’t do it,” she tells her support group later. Tambor, as Maura, embodies all the regret and hope of a character with decades of suppressed longing behind her. “They are so selfish,” she says. “I don’t know how it is I raised three people who cannot see beyond themselves.”

The major theme of Transparent is established here, at the outset of the series: the thin line between self-actualization and self-absorption. To be sure, the Pfefferman children are real pieces of work. The eldest, Sarah (Amy Landecker), begins the show as a twenty-first-century rendition of the unhappy housewife described in The Feminine Mystique. She lives with her husband (Rob Huebel), who works in real estate, and their two children in one of those big TV houses full of stainless-steel appliances. We see her preparing the kids’ lunches in bento boxes and driving them to their private school as “Free to Be . . . You and Me” plays on the stereo. Josh (Jay Duplass), the middle sibling, is a joylessly promiscuous A&R man. He inhabits a light-filled condominium with glass balconies on L.A.’s Eastside, and manages a band called Glitterish, whose lead singer, a wispy blonde, he is dating. He, too, has a secret past: as a teenager, he had a sexual relationship with the family babysitter. Josh thinks it was love, but everyone else believes he was molested. In any case, the family harbors unexamined shame about their failure to protect him. The youngest Pfefferman, Ali, is in her early thirties. She is broke, unemployed, and directionless, like an aged-out cast member of Girls who has wandered onto the wrong set.

The first season focuses on Maura’s coming out to each of her children, and on the coincidental upheavals in their lives. By the last episode, Sarah has left her husband for a woman named Tammy Cashman (Melora Hardin), Josh has lost his girlfriend and his job, and Ali still hasn’t figured out what to do with her life. If Maura is an exemplar of self-actualization — the person who, after suffering for so long, finally expresses her true self — her children represent the dark side of a world in which existential decisions are no longer scripted by religious doctrine and social custom but must be discerned through personal exploration. This can result, it turns out, in narcissism and fickleness.

Transparent deploys many of the normalizing strategies of comedic television: the absorption of difference into the nuclear family; the reactionary faux pas (think of the moment in Annie Hall when Diane Keaton tells Woody Allen, “You’re what Grammy Hall would call a ‘real Jew’ ”; in Transparent, a wedding photographer calls Maura “sir”); the sassy supporting character from a different social background who puts the privilege of the main characters into perspective — in this case, Maura’s friend Davina (Alexandra Billings), “a fifty-three-year-old, ex-prostitute, H.I.V.-positive woman-with-a-dick.” There’s also a fair amount of what the show’s creator, Jill Soloway, has called “transplaining.” Through Maura’s experience, several stereotypes and misconceptions about what it means to be trans are addressed. The viewer learns about the range of body modifications that people choose to make, the side effects of taking testosterone and estrogen, and the difference between gender identification and sexual orientation. When Maura’s hormone doctor asks her whether she “tops” or “bottoms,” Maura looks baffled. The doctor’s response — “Mrs. Pfefferman, do yourself a favor and get to know your body” — is directed as much to the audience as it is to Maura, who finds herself suddenly beset by the physical insecurity and sexual uncertainty of an adolescent.

The first season of Transparent aired in 2014. In the spring of 2015, Bruce Jenner, the former Olympic decathlete and popular reality-television star, came out as a trans woman. Nearly 17 million people watched the 20/20 interview in which Jenner made the announcement. Soloway has said that these developments changed the way she approached Season 2 of Transparent, which was released in November. “I think the world has caught up with Trans 101,” she told E! Online. “We get to just tell stories and let Maura be a little more vulnerable and let her be a little more of a screwup and not have to be the perfect character.”

Jenner’s coming out also gave Soloway the confidence to take a more critical view of certain aspects of identity politics, such as the cumbersome jargon and the competing narratives of self-righteousness. Throughout its second season, Transparent reveals the ways in which new ideas about gender and sexuality sometimes reproduce the cruelty and the exclusionary practices that they seek to remedy. The show is at its best when satirizing the new dogmas and pseudo-philosophies that are presented as alternatives to the traditions of family and religion. In this sense, Soloway’s vision is less radical than it is liberal; she wants to reform, rather than reinvent, society.

The season begins, fittingly, with a wedding. Sarah is marrying her new girlfriend. If Tammy’s name and bad taste in interior decorating hadn’t already tipped us off, we realize that she is doomed as soon as Sarah begins to walk down the aisle. The ceremony is a parody of the post-religious wedding, with its efforts to rid itself of all traces of patriarchy and inequity while still maintaining gravitas. Sarah looks like she has dressed as a corpse bride for Halloween, the guests have all been asked to wear white, and the reform rabbi gets proceedings under way by saying, “In the words of Meshell Ndegeocello.”

Tammy, of course, has written her own vows. (“To make love to you, to make up love with you.”) As they are being recited, Sarah looks up and sees a prop plane trailing a banner bearing the URL webuyuglyhouses.com. Later, during “Hava Nagila,” she has a panic attack in the bathroom. Josh summons the rabbi, Raquel, whom he’s recently begun dating. She determines that it’s not too late to cancel the wedding. “Jewish-wise you are married, but, I mean, legally you’re not, yet,” she says. “So what is a wedding, then?” Ali asks. “It’s a ritual, it’s a pageant,” Rabbi Raquel says. “It’s like a very expensive play.”

This episode is titled “Kina Hora” — Yiddish for “evil eye” — and over the course of the season the Pfeffermans do seem to fall under a curse. Josh, who has gotten Rabbi Raquel pregnant, is unable to muster even a semblance of duty or compromise when their relationship falls apart. Jay Duplass excels at playing a person who is incapable of reckoning with his emotions. If the other characters spend too much time investigating their every feeling, Josh reminds us of the perils of the unexamined life. His beard, which gets ever more unkempt as the season progresses, signifies a cancer of the soul. He is beset by a series of catastrophes until, in the eighth episode, we find him doubled over by the side of the highway having a breakdown. “You’re a spiritual person,” he is told at one point. “You just don’t have a practice.”

While experimenting with her newfound lesbianism, Ali blithely tramples on the feelings of her best friend, Syd (Carrie Brownstein), who has been secretly in love with her since eighth grade. The fluidity of sexual orientation is treated casually on Transparent. When a man asks Sarah whether the reason she won’t go out with him is that she’s gay, she looks annoyed. “I mean how do you even know, really, if you’re gay?” she asks. He suggests deciding on the basis of which genitals you think of when you’re falling asleep at night. This doesn’t work for Sarah, whose sexual fantasies are about getting spanked.

For her part, Maura discovers that having suffered doesn’t make you immune from inflicting pain on others. She confronts the privileges that were conferred on her in her life as a man, and her own capacity for hurtful judgment, which alienates both her ex-wife and her best trans friend. The show explores the conflicts between the trans movement and radical feminism when Maura and her daughters attend a fictionalized version of the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, whose rules stipulate that attendees be “womyn born womyn.”

The critic Vivian Gornick wrote that “in great novels we always feel that the writer, at the time of the writing, knows as much as anyone around can know, and is struggling to make sense of what is perceived somewhere in the nerve endings if not yet in clarified consciousness.” Transparent demonstrates that even if we have mastered the basics of identity politics, nobody has quite figured out the best way to integrate new formulations of identity into old institutions. One of the show’s strengths is the way that it distributes the most offensive lines among its characters — no one has a monopoly on insensitivity. Conversely, no one has suffered so much that he or she is beyond reproach. Now that we are all free to be you and me, Soloway suggests, perhaps it is worth consulting religion, which may have more than oppression to offer. After Sarah seeks guidance from a life coach, a marriage counselor, a pot dealer, and a dominatrix, she is shown, in the final episode of the season, entering a synagogue.