Discussed in this essay:

Labor of Love: The Invention of Dating, by Moira Weigel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 304 pages. $26.

Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table, by Ellen Wayland-Smith. Picador. 320 pages $27.

“The reason why Wall Street guys party so hard is because they’re not happy with their jobs,” Roselyn Keo, an enterprising stripper turned con woman, told Jessica Pressler of New York magazine last year:

You make money, but you’re not happy, so you go out and splurge on strip clubs and drinking and drugs, then the money depletes and you have to make it again. The dancers are the same way. You make money, but then you’re depressed, so you end up shopping or going on vacation, and the money depletes, so you go back . . .

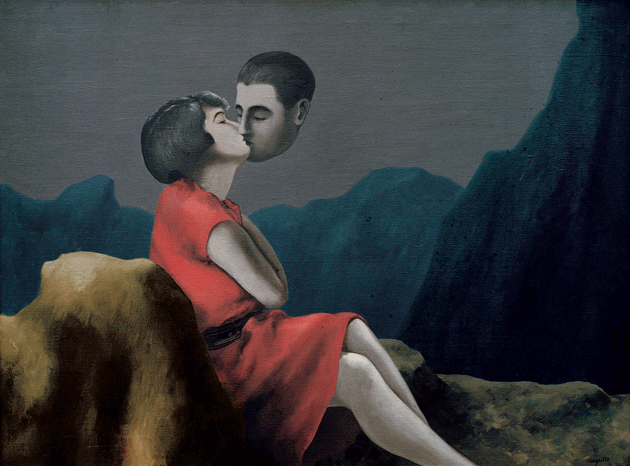

I imagine that Moira Weigel, the author of Labor of Love, a lively new history of dating, would enjoy this story. The strippers and the finance guys they eventually rip off have much in common, not least the exhausting symmetry of their hamster-wheel routines: work is a slog that never ends, until finally it’s time to go out and spend the money — at which point you notice that leisure feels like kind of a slog as well.

It’s not news that all sorts of supposedly fun activities — going to the gym, playing video games, maintaining a social-media presence — have grown harder to distinguish from work. But dating, Weigel would have you understand, is among the worst. Its dissatisfactions are similar to those involved in many a job: a vast investment of time, effort, and emotion for inadequate reward; a lot of responsibility and not much power; and a setup that feels rigged against you. The physical demands aren’t negligible, either. New York dating, at least from the sidelines, looks taxing enough, but I hear that in California there’s such a thing as a running date, where, presumably, instead of grabbing a drink or a coffee, you throw on your spandex and sweat until the best man wins.

Dating feels like work, Weigel tells us, because it is and always has been. She traces its beginnings to the late nineteenth century. In chapters loosely organized around themes (“Tricks,” “Likes,” “Niches”), she moves through the frantic, competitive dating of Twenties and Thirties co-eds, the more stable pairings of the Forties and Fifties, and on into the fractured present. The book’s early pages describe women indoors: the girls who sat with their parents, waiting for their suitors to call; the sex workers who received clients one by one, like “artisans” or “small-business owners.” As the century turned, more unmarried women joined those flooding into the cities in search of work. There, dating meant a free dinner for women who couldn’t afford to buy one, or free entry into night spots that required a male escort. Brothels and red-light districts sprang up, and even those “public women” who weren’t charging — “charity cunts” was one of the more colorful names given to them — sometimes risked arrest. Compared with the older tradition of home visits, going out offered both greater personal freedom and greater social mobility: shop assistants and stenographers could marry their customers and bosses; an heiress could marry a popular songwriter (in this case, Irving Berlin). All kinds of couples could escape family surveillance; out of the parlors and into the parks, they found a certain privacy in public. Reading Weigel on this period, I was reminded of the feedback left by one young man after a 1939 preview of Ernst Lubitsch’s Ninotchka: “Great picture . . . I laughed so hard, I peed in my girlfriend’s hand!”

Weigel attributes the rise of “going steady” — “all of the worst features of marriage and none of its advantages,” as Dorothy Dix wrote — in part to a shortage of men during World War II but mainly to a surfeit of cash after the troops returned. Many teenagers now had what would have been the “disposable income of an average family” only a few years earlier. “By the 1950s,” Weigel writes, “shopping had become the go-to metaphor” for dating, a comparison that she sees as symptomatic of a deeper link between the two phenomena. She herself has a soft spot for such language, describing the postwar period as one of “romantic full employment” or musing, “Does every year of hooking up simply put us in the emotional equivalent of more student debt?”

Yet the vocabulary of economics has bled into discussions of love at least since Freud, who wrote about the investments of the libido, and it’s hard to know how much that says about the way people actually date. Advertisers, of course, routinely use the language of dating to sell other things: for years, an online grocery service I’d used a few times in London sent me plaintive emails about the “Lidija-shaped hole” in its life; an airline, despite reassuring me that “we can take it slow if that’s your speed,” immediately skips all the way to “what to expect when expecting our emails.”

If the connections between work, commerce, and love seem fuzzy in Weigel’s telling, perhaps that’s the point. We all know that the economy determines many of our social and sexual mores, but the details of how it does so are hard to tease out with any precision. Weigel suggests, for instance, that the infamous hookup (defined, she notes, not so much by actual promiscuity as by the obligation to project nonchalance about whatever sex you do have) is a reaction to economic insecurity. College students must now be ready for careers in which “they cannot count on anything,” and must therefore cultivate “steely” hearts. Yet she concedes that hookup culture is a limited phenomenon — only a relatively small, white, affluent group appears to be taking part in it, and these students surely have a lot less to fear from the “precarious” economy than their peers.

As her title suggests, Weigel recategorizes whole swaths of what we think of as dating, love, and reproduction as forms of labor — and labor that disproportionately falls to women. Although she nods here and there to gay life, her focus is mostly on heterosexual dating, which she tends to figure, from the woman’s perspective, as a scary movie. When straight men aren’t violent, they’re often frighteningly indifferent. Weigel diagnoses Richard Gere’s commitment-phobic character in Pretty Woman as a “textbook sociopath” and the film’s plot as “basically” identical to that of American Psycho. A man who wants to understand how a woman feels when going out at night, a friend of Weigel’s suggests, should try watching Fatal Attraction before he leaves the house. At the very least, men are exploiting women’s labor: it’s women who must spend time and money on their looks, hide their feelings on dates, coax and plan and play hard to get, freezing their eggs rather than make a potential boyfriend uncomfortable by seeming in a hurry. The metaphor of the biological clock, Weigel points out, is a useful way to “make it seem only natural — indeed, inevitable — that the burdens of reproducing the world fall almost entirely on women.”

Evidence that straight men are work-shy in the sphere of love, Weigel argues, is easy to find. Just listen out for how often they’ll describe a woman they’ve dumped as demanding or not worth the effort. Analyzing retrograde self-help books for both sexes (such as Ellen Fein and Sherrie Schneider’s The Rules and Neil Strauss’s The Game), she insists that dating is “work for women and recreation for men.” Yet once we’re labeling so many other things as work, this seems an arbitrary line to draw. Weigel quotes Strauss as saying, “For me, meeting girls takes work,” and another pickup artist describing bars and clubs as “different levels on a video game I had to get through.” A whole network of books and websites and motivational speeches exists to recommend to men which tricks to learn and which insufficiently aggressive instincts to suppress. Those who follow this advice no doubt have all sorts of failings, but laziness hardly seems one of them.

Weigel’s real problem with self-help, though, is that it treats social problems as individual ones, and so trains you above all in self-blame. Later in the book, as she reiterates how unjustly distributed reproductive labor still is, she weakly gestures at more imaginative forms of social organization. What The Rules rules out is “the possibility that a connection between two or more people might be capable of changing the conditions in which they live.” She’s fairly scathing, however, about those who tried this in the Sixties and Seventies. Free-love types mostly re-created the gendered power dynamics of earlier generations, and they put too much emphasis on the individual freedom to do what you want, which Weigel equates with consumerism. It’s no coincidence, she claims, that Jane Fonda and Bobby Seale moved seamlessly from radicalism to commerce: free-market evangelists and free lovers were essentially sisters under the skin. The hippies “tore down walls,” but “did not build a new world.”

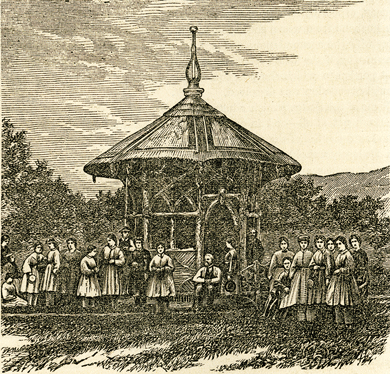

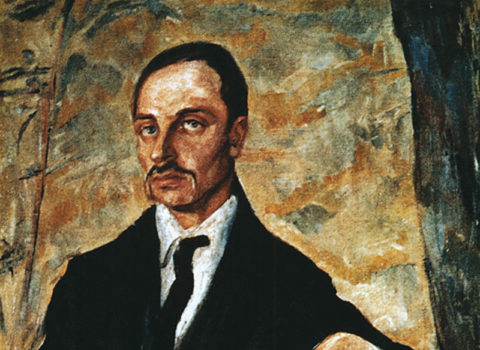

For a serious attempt to revolutionize both labor and the relations between the sexes, we can go back further, to a moment at least as turbulent as the years when dating began. In the first half of the nineteenth century in the United States, millennial Christian sects flourished among a constellation of other cultish movements. Ellen Wayland-Smith, in her new book, Oneida, notes that this “reform” culture of “phrenologists and feminists, abolitionists and vegetarians, temperance activists and mesmeric healers” made for a potent mishmash, which was skewered by Henry James in The Bostonians. One of his targets was the “simply hideous” John Humphrey Noyes, an ancestor of Wayland-Smith’s and the founder of one of the stranger experimental communities in American history.

The Oneida commune, which had its roots in Vermont but became fully established in upstate New York, began as Noyes’s attempt to solve a set of problems not unlike the one Weigel addresses today: mating rituals as wretched and unfair as the economic circumstances and working practices they reflected. “The law of marriage ‘worketh wrath,’ ” Noyes wrote, by keeping men in competition and women in bondage and encouraging a corrosive “egotism for two.” Private property and factory labor had similar effects. Noyes aimed to establish an expanded family that would act as a pilot scheme, eventually converting those around it to a system based on spiritual love and fellowship, in which individuals would be absorbed into a larger purpose, without selfishness or exploitation.

Unlike the proto-socialist model followed by places like Brook Farm (immortalized in Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance), Noyes’s was centered on religion, and the adventurous sexual practices he advocated were carefully integrated into his theology. He considered both marriage and slavery morally dubious, being “institutions invested in the ownership of persons,” and hired labor — then commonly figured as “wage slavery” — fell into the same questionable realm.

Noyes began by winning over some of those around him to his strain of revivalism. (His mother, who Monty Python–ishly continued to remind him that he had “faults the same as other people,” was one of the tougher nuts to crack.) In 1838, he married Harriet Holton, a conveniently wealthy convert — promising not to “monopolize and enslave her heart or my own” — and in the early 1840s he set up a small community. Noyes espoused a notion of “spiritual wives” that was not uncommon among contemporary Christian sects, and he and Holton were soon exchanging confessions of mutual longing with another couple in the group. In the spring of 1846, they agreed to save the consummation of their extramarital desires until the anticipated reign of saints on earth, but they only lasted a month or two before deciding that God was waiting for them to make the first move.

The group that would become the Oneida community gradually adopted “complex marriage,” and over the next few years, several hundred people began to live according to Noyes’s system. Intellectual and physical work was shared and rotated, men and women had equal decision-making power, and property was communal. Wayland-Smith expertly lays out the philosophy behind their initial “working school” model of enterprise, which prioritized the well-being of all those who contributed their labor to it. They favored a kind of “communo-capitalism,” run “under the stimulus of love.” In their optimistic schema for a more just world, instead of a Marxist plan in which the state would take over the means of production, private tycoons would continue to run industry undisturbed, “but would simply cease to exploit labor.” The community instituted a practice of “mutual criticism,” group feedback to each person on his or her character and conduct, to be accepted in dignified silence. (Wayland-Smith notes in passing that two members appear to have been eaten by cannibals in the East Indies after encouraging the locals to give mutual criticism a try.) There was special emphasis on giving up selfish attachments: “sticky love,” or sexual possessiveness, was particularly frowned on, and likewise “philoprogenitiveness,” the attachment to one’s own children over other people’s. Both proved difficult to eradicate. “If a man comes into this Association with a wife that he has to watch and reserve from others,” Noyes told the group, “he has brought a cask of powder into a blacksmith’s shop.”

For around ten years, Noyes ran a eugenics program. (He’d long been in favor of sex between siblings, though the record is silent on whether he put that part of his theory into practice with his own sisters.) His hope was that the virtues inculcated by years of determined self-improvement and group reflection would be “fixed in the blood” and passed down via a system of inbreeding that he called “stirpiculture.” Noyes’s eventual aim was to produce immortal stock. Half of the fifty-eight children born at Oneida in the decade from 1869 were his blood relations; he fathered ten of those himself.

Notwithstanding its dystopian elements, Noyes’s approach had benefits for women, at least compared with what they endured in the outside world. Aside from their ability to pursue work that interested them, they were also mostly freed from a grueling succession of pregnancies and miscarriages, because Noyes believed in the equal or even superior economic and spiritual value of non-procreative sex. He winningly likened it to the importance of a melon’s pulp relative to its seeds: the former has primacy, “for we feel that the chief end and value of the fruit is realized when it is eaten and converted to human enjoyment, even though its seeds are thrown away, and its propagative destiny is left unregarded.” (The analogy, it must be said, rather falls apart once you look at it from the perspective of the melon.) The men of the community accordingly adhered to a Sting-like policy of non-ejaculation: Wayland-Smith reports that Noyes, always partial to “awkward sexual metaphors,” liked to compare “the indiscriminate emptying of one’s seed into a woman to the discharge of a blunderbuss gun into a friend’s face.”

What set Oneida apart from most other such experiments was its longevity — thirty years under Noyes’s full system, then a long afterlife via the joint-stock Oneida company, which made traps, silk thread, and, most successfully, silverware. After an initial period of sharing the work equally among themselves, the Oneidans decided that they had to produce more to compete on the open market, and they began to take on wage laborers, whose status and role were markedly different.

According to Wayland-Smith, one can find a clear picture in community members’ writings from the 1860s and 1870s of “an ideology stretched to the breaking point.” The core members simply couldn’t agree on whether their factory workers should have the same advantages as the rest of them, and the company became increasingly hard to distinguish from any other firm. Indeed, in the twentieth century, Oneida was to become a byword for middle-class American values, flogging flatware to status-conscious couples via the cozily domestic imagery of its advertising. The experiment started to unravel in the late 1870s, when Noyes himself left in the face of increasing challenges to his authority. The practice of complex marriage ended by mutual agreement on August 28, 1879, and most made the switch quietly, though Wayland-Smith writes that Noyes’s niece, the indefatigable Tirzah Miller, “had sex with James Herrick in the morning, Erastus Hamilton in the afternoon, and with Homer Barron in the evening in a frenzied last hurrah.” Once the community had fully dissolved into a business, the families who’d been central to the project remained so, and apparently continued to intermarry at a curious rate, but they mostly distanced themselves from the sexual avant-gardism of the early Oneidans. After one too many inquiries about their archives from curious gynecologists and sexology researchers (including Alfred Kinsey), they destroyed thousands of pages of letters, diaries, case histories, and medical records in a ritual burning.

Romantic love, Weigel concludes, is “less noun than verb.” To recognize it as labor may allow us to “reclaim it, to insist that it be distributed equally and directed towards the ends that we in fact desire.” She suggests that if we chose to take the “critical energies” that self-help asks us to aim inward and turn them in the opposite direction, “we might come up with concrete fixes that could make dating — and much besides dating — better.” It remains tantalizingly unclear, though, just how a more enlightened approach to dating would lead to far-reaching social and political change. She mentions “better health care, child care, and maternity leave policies” as possible goals, but I have to assume she does not mean that, had we not all been busy fixing our hair and smiling diligently at our chosen sociopath over dinner, we might have achieved single-payer by now. There are lots of highly particular reasons that the Oneida commune’s social experiment ended. But its inherent contradictions, the ways in which it failed to do what it promised — its patriarch decreeing who should bear whose child, its ladies winding silk thread around spools for a leisurely afternoon while child laborers from outside worked twelve-hour shifts — certainly seem to have helped undermine it. Told in Wayland-Smith’s evenhanded tone, the story raises some intriguing questions. How far might a group, by effort of will, hope to remake patterns of love and reproduction, and what old expectations and inequities will it inevitably bring along in the attempt? These are precisely the sorts of questions that Weigel’s analysis points us toward, and yet she stops short of addressing them.

Toward the end of Labor of Love, Weigel invokes Marx, implying a similarity between his description of alienated labor and what happens when women, hectored into chasing after men while feigning an attractive indifference to them, are forced to become estranged from their own feelings. To connect these two phenomena feels like a stretch, but the resulting awkwardness is only one of several puzzling side effects of Weigel’s attempt to recast almost everything involved in love and dating as labor, a move that risks robbing the term of its usefulness. Still, the brief reference to historical materialism draws the reader’s attention to an issue that Weigel herself has neglected: can we remake love without first remaking work, social conditions before economic ones? Wayland-Smith’s book hints at an answer: a structural problem will probably require a remedy of the same kind. It seems fair to assume that when Weigel imagines changing the intimate relations between the sexes as a means to making broader changes, an experiment like Noyes’s is not what she has in mind. Nonetheless, it’s an instructive example of how difficult any such change would be, even on a small scale, and even given a quite remarkable investment of time, resources, planning, and near-lunatic conviction. (Noyes, one scholar points out, took nine years between coming up with his idea for complex marriage and instigating it — unlike the hippies Weigel faults, he was careful not to break the old order until he had something to replace it with.) It’s difficult to read Wayland-Smith’s account without suspecting that any attempt to transform material conditions by spiritual and erotic means, while it sounds much more fun than the reverse, would be a hopelessly quixotic venture.

Weigel describes the optimistic glow that possessed her after falling in “two kinds of love” — with the man who is now her husband and with a female friend whose help she credits in the writing of this book. “I began to feel desire,” she writes, “as a movement in me that reached outward, yearning to act upon the world.” But yearning alone, as I wish I could convey to my importunate airline, is rarely enough to get you the results you want. Wayland-Smith notes that according to Marx and Engels, the likes of Noyes, despite their best intentions, “remained trapped within the quaint bourgeois ideology that maintained that social progress would come by cultivating virtue in the individual” rather than through “structural reforms of the capitalist mode of production.” Weigel’s intuition that our dating lives feel unsatisfactory not just because of human error and the vagaries of love but because they reflect in every detail the unjust, exploitative economic and political system within which they take place, is a very dark one — this, too, surely, is the stuff of horror movies, where the threat is both inside and outside us, not to be escaped. That she has chosen such a worthy foe makes it seem all the stranger that when the time for battle approaches, Weigel turns coy. What exactly are these mysterious new ways of loving and living toward which she hopes we will direct our efforts?

The book’s central argument dips into and out of view as she jumps from theme to theme, but what’s clear is that Weigel sees herself, unlike those free lovers of the Sixties, as a kind of emotional radical. “Our challenge,” she writes, “is to find ways to honor love properly without falling back into outdated patterns. We might think of this as a third sexual revolution.” The change she envisages has two parts: men must at long last take on their fair share of love’s labor, and then we might all begin to forge a brave new world. In the absence of any real examples — and given Weigel’s lapses into the language of personal growth — one suspects that “to honor love properly” under this new dispensation may mean little more than enjoining men to get in touch with their feelings, abandon their fear of commitment, and become more “mindful, kind, and appreciative” partners. Although such developments couldn’t hurt, they don’t sound especially revolutionary.

If Weigel fails to notice that transforming love — even assuming we could find ways to do so — wouldn’t adequately address our more material difficulties, it may be because she has misstated the problem that most concerned her in the first place. Underneath her larger story of American dating lies a smaller, older tale, which shows itself most clearly at the beginning and the end of her book. Surprisingly, it’s a marriage plot, the kind familiar from novels of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Weigel says that her initial idea for Labor of Love was sparked by a salutary experience with an “older, handsome,” and, we gather, ever so slightly villainous man, and that she was then spurred on in her work by a sympathetic friend and, crucially, by falling for a second man, the one who became her husband: “It was through this relationship,” she writes, “that I first came to see who I was and what happiness meant.” Quite how we are to read this rather conventional story of success against the dating market’s odds as a radical critique of the American status quo is a question that remains outside her book’s neat frame. Yet it isn’t so hard to understand how one might mistake for revolutionary fervor a feeling that seems, in essence, more akin to the undeniable satisfaction of a job well done.