“Welcome to the world of strategic analysis,” Ivan Selin used to tell his team during the Sixties, “where we program weapons that don’t work to meet threats that don’t exist.” Selin, who would spend the following decades as a powerful behind-the-scenes player in the Washington mandarinate, was then the director of the Strategic Forces Division in the Pentagon’s Office of Systems Analysis. “I was a twenty-eight-year-old wiseass when I started saying that,” he told me, reminiscing about those days. “I thought the issues we were dealing with were so serious, they could use a little levity.”

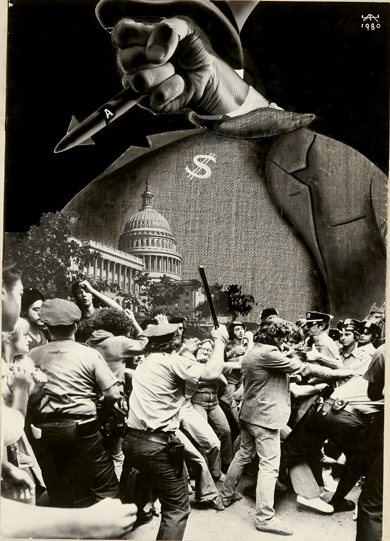

The Team of Warmongers, 1959, a photomontage by Aleksandr Zhitomirsky. The text on the jerseys reads “Admiral Burke,” “General Twining,” “McElroy,” “General White,” and “General Norstad.” The text on the referee’s sleeve reads “Wall Street.” A retrospective of the Soviet propaganda artist’s work is currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago. The accompanying catalogue was published in October by the Art Institute and Yale University Press. All artwork © Vladimir Zhitomirsky. Courtesy the Ne boltai! Collection and the Art Institute of Chicago

His analysts, a group of formidable young technocrats, were known as the Whiz Kids. Their iconoclastic reports on military budgets and programs, conveyed directly to the secretary of defense, regularly earned the ire of the Pentagon bureaucracy. Among them was Pierre Sprey, who later helped to develop the F-16 and A-10 warplanes. He emphatically confirmed his old boss’s observation about chimerical threats. “It was true for all the big-ticket weapons programs,” he told me recently. “But although we pissed off the generals and admirals, we couldn’t stop their threat-inflating, and their nonworking weapons continued to be produced in huge quantities. Of course,” he added with a laugh, “the art of creating threats has advanced tremendously since that primitive era.”

Sprey was referring to the current belief that the Russians had hacked into the communications of the Democratic National Committee, election-related computer systems in Arizona and Illinois, and the private emails of influential individuals, notably Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta — and then malignly leaked the contents onto the internet. This, according to legions of anonymous officials quoted without challenge across the media, was clearly an initiative authorized at the highest level in Moscow. To the Washington Post, the hacks and leaks were unquestionably part of a “broad covert Russian operation in the United States to sow public distrust in the upcoming presidential election and in U.S. political institutions.”

In early October, this assessment was endorsed by James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, and the Department of Homeland Security. Though it expressed confidence that the Russian government had engineered the D.N.C. hacks, their curiously equivocal joint statement appeared less certain as to Moscow’s role in the all-important leaks, saying only that they were “consistent with the methods and motivations of Russian-directed efforts.” As for the most serious intrusion into the democratic process — the election-system hacks — the intelligence agencies took a pass. Although many of those breaches had come from “servers operated by a Russian company,” the statement read, the United States was “not now in a position to attribute this activity to the Russian Government.”

The company in question is owned by Vladimir Fomenko, a twenty-six-year-old entrepreneur based in Siberia. In a series of indignant emails, Fomenko informed me that he merely rents out space on his servers, which are scattered throughout several countries, and that hackers have on occasion used his facilities for criminal activities “without our knowledge.” Although he has “information that undoubtedly will help the investigation,” Fomenko complained that nobody from the U.S. government had contacted him. He was upset that the FBI had “found it necessary to make a loud statement through the media” when he would have happily assisted them. Furthermore, these particular “criminals” had stiffed him $290 in rental fees.

As it happened, a self-identified solo hacker from Romania named Guccifer 2.0 had made public claim to the D.N.C. breaches early on, but this was generally written off as either wholly false or Russian disinformation. During the first presidential debate, on September 26, Hillary Clinton blithely asserted that Vladimir Putin had “let loose cyberattackers to hack into government files, to hack into personal files, hack into the Democratic National Committee. And we recently have learned that, you know, that this is one of their preferred methods of trying to wreak havoc and collect information.”

By “wreak havoc,” Clinton presumably had in mind such embarrassing revelations as the suggestion by a senior D.N.C. official that the party play the religious card against Bernie Sanders in key Southern races, or her chummy confabulations with Wall Street banks, or her personal knowledge that our Saudi allies have been “providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIL and other radical Sunni groups.” It made sense, therefore, to create a distraction by loudly asserting a sinister Russian connection — a tactic that has proved eminently successful.

Donald Trump’s rebuttal (“I don’t think anybody knows it was Russia that broke into the D.N.C. . . . It could be somebody sitting on their bed that weighs four hundred pounds, okay?”) earned him only derision. But a closer examination of what few facts are known about the hack suggests that Trump may have been onto something.

CrowdStrike, the cybersecurity firm that first claimed to have traced an official Russian connection — garnering plenty of free publicity in the process — asserted that two Russian intelligence agencies, the FSB and the GRU, had been working through separate well-known hacker groups, Cozy Bear and Fancy Bear. The firm contended that neither agency knew that the other was rummaging around in the D.N.C. files. Furthermore, one of the hacked and leaked documents had been modified “by a user named Felix Dzerzhinsky, a code name referring to the founder of the Soviet Secret Police.” (Dzerzhinsky founded the Cheka, the Soviet secret police and intelligence agency, in 1917.) Here was proof, according to another report on the hack, that this was a Russian intelligence operation.

“OK,” wrote Jeffrey Carr, the CEO of cybersecurity firm Taia Global, in a derisive blog post on the case. “Raise your hand if you think that a GRU or FSB officer would add Iron Felix’s name to the metadata of a stolen document before he released it to the world while pretending to be a Romanian hacker.” As Carr, a rare skeptic regarding the official line on the hacks, explained to me, “They’re basically saying that the Russian intelligence services are completely inept. That one hand doesn’t know what the other hand is doing, that they have no concern about using a free Russian email account or a Russian server that has already been known to be affiliated with cybercrime. This makes them sound like the Keystone Cops. Then, in the same breath, they’ll say how sophisticated Russia’s cyberwarfare capabilities are.”

In reality, Carr continued, “It’s almost impossible to confirm attribution in cyberspace.” For example, a tool developed by the Chinese to attack Google in 2009 was later reused by the so-called Equation Group against officials of the Afghan government. So the Afghans, had they investigated, might have assumed they were being hacked by the Chinese. Thanks to a leak by Edward Snowden, however, it now appears that the Equation Group was in fact the NSA. “It doesn’t take much to leave a trail of bread crumbs to whichever government you want to blame for an attack,” Carr pointed out.

Bill Binney, the former technical director of the NSA, shares Carr’s skepticism about the Russian attribution. “Saying it does not make it true,” he told me. “They have to provide proof. . . . So let’s see the evidence.”

Despite some esoteric aspects, the so-called Russian hacks, as promoted by interested parties in politics and industry, are firmly in the tradition of Cold War threat inflation. Admittedly, practitioners had an easier task in Selin’s day. The Cold War was at its height, America was deep in a bloody struggle against the communist foe in Vietnam, and Europe was divided by an Iron Curtain, behind which millions chafed under Soviet occupation.

Half a century later, the Soviet Union is long gone, along with the international communist movement it championed. Given that Russia’s defense budget is roughly one tenth of America’s, and that its military often cannot afford the latest weapons Russian manufacturers offer for export, resurrecting this old enemy might seem to pose a challenge to even the brightest minds in the Pentagon. Yet the Russian menace, we are informed, once again looms large. According to Defense Secretary Ashton Carter, Russia “has clear ambition to erode the principled international order” and poses “an existential threat to the United States” — a proclamation endorsed by a host of military eminences, including General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, his vice-chairman General Paul Selva, and NATO’s former Supreme Allied Commander, General Philip Breedlove.

True, relations with Moscow have been disintegrating since the Bush Administration. Yet Russia achieved formal restoration to threat status only after Putin’s takeover of Crimea in February 2014 (which followed the forcible ejection, with U.S. encouragement, of Ukraine’s pro-Russian government just a few days earlier). Russia’s intervention in Syria, in the fall of 2015, turned the chill into a deep freeze. Still, the recent accusation that Putin has been working to destabilize our democratic system has taken matters to a whole new level, evoking the Red Scare of the 1950s.

At the core of the original Cold War threat was the notion that the Soviets, notwithstanding the loss of 20 million lives and the utter devastation of their country in World War II, somehow maintained a military technologically equal to that of the United States, and far greater in numbers. Portraying the United States as militarily vulnerable might have seemed tricky. There was, after all, the nation’s million-man army, its 900-ship navy, its 15,000-plane air force, and a strategic nuclear arsenal guaranteed, as its commander, General Curtis LeMay, announced in a 1954 briefing, to reduce Russia to a “smoking, radiating ruin in two hours.”

Nevertheless, public belief in the Soviet Union as an existential threat (not that the phrase existed then) was undimmed. The enemy to be held in check appeared awesome. No less than 175 Soviet and satellite divisions were reportedly poised on NATO’s eastern border, vastly outnumbering the puny twenty-five NATO divisions defending Western Europe. U.S. military officials regularly delivered somber warnings that the Soviets were also close to overtaking us in the quality of their military hardware. In 1956, when the Soviet defense minister, Georgy Zhukov, informed a visiting U.S. delegation that its estimate of Soviet military strength was “too high,” the visitors brushed this aside as obvious disinformation. They returned home, as one of them wrote later, convinced that “the Soviets were rapidly reaching the point where they could successfully challenge our technical superiority.”

Zhukov was telling the truth. Soviet military units were to a large extent undermanned, badly trained, and ill equipped — those menacing divisions in East Germany had only enough ammunition for a few days of fighting. An exhaustive 1968 study by the Systems Analysis Office concluded that the two sides in Europe were actually equal in numbers. But since this dose of reality ran counter to the official story, it had no effect on military planning, and certainly none on defense spending.

The “missile gap,” conceived by the Air Force and heavily promoted by John F. Kennedy as he ran for the White House in 1960, stands out as a preeminent example of Cold War threat inflation. Kennedy, briefed by the CIA on President Eisenhower’s orders, knew perfectly well that no such gap existed — except in America’s favor. He campaigned on the lie nonetheless, and once in office, he felt it necessary to spend billions of dollars on a thousand Minuteman ICBMs. (In accord with Selin’s maxim, a large percentage of the missiles were inoperable thanks to a faulty guidance system.)

So it continued. Throughout the Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties, the Soviet threat reliably prompted infusions of cash into the defense complex, to the gratification of its many functionaries, not least the congressmen and senators who were amply rewarded for their role in lubricating the process. Meanwhile, the “American threat” was performing a similar role on the other side of the Iron Curtain, sustaining the Soviet military’s grip on the commanding heights of a comparatively impoverished domestic economy. Thus, the Soviets eagerly matched the U.S. missile buildup until they, too, had the ability to lay waste to the planet several times over.

Maintaining these huge forces on hair-trigger alert, ready to launch on a few minutes’ notice, was an intricate business, requiring radar arrays, high-powered computers, and elaborate communication networks. Though profitable for participants, these systems had potentially catastrophic consequences. In November 1979, for example, Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national-security adviser, was awoken at three in the morning with the news that the NORAD headquarters in Colorado had detected Russian nuclear missiles streaming toward the United States; they would begin detonating in a matter of minutes. A second call moments later confirmed the report. Brzezinski was on the point of calling Carter, who would have had three minutes to decide whether to precipitate an all-out nuclear war, when a third call announced it had all been a mistake. A NORAD computer had inexplicably started running a software program simulating a Russian attack. Another false alert occurred the following year, this one generated by a single malfunctioning computer chip. The Soviets, meanwhile, developed the Perimeter system, by which alerts of an incoming attack would automatically trigger a counterstrike.

A decade later, the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union appeared to consign the long-standing threat of nuclear annihilation to the ash can of history. Europe was (almost) stripped of tactical nuclear weapons, and the United States and Russia agreed to reduce their strategic arsenals to 6,000 warheads on either side. American nuclear bombers (though not missiles) were taken off alert. Although the Russians had inherited the remains of the Soviet arsenal, they could not afford to maintain or update decaying systems. In the words of Bruce Blair, a leading authority on nuclear weaponry who once served as a Minuteman launch-control officer, our perennial opponent “effectively disarmed.”

Unsurprisingly, there was much optimistic talk of a “peace dividend” for the American taxpayer. If the threat propelling all that spending over the years had disappeared, surely defense budgets could and should be slashed. Our fighting forces did indeed shrink — by 1997, half the Air Force’s tactical fighter wings had been disbanded, while the Army had lost half its combat units, and the Navy more than a third of its ships. Overall military spending, on the other hand, remained extremely high. As Franklin “Chuck” Spinney, then an analyst at the Defense Department and long an acute observer of such trends, noted presciently in 1990: “The much smaller post–Cold War military will require a Cold War budget to keep it running.” Spinney was overoptimistic: allowing for inflation, defense spending has never once fallen below the Cold War average.

This mismatch, astonishing to the uninitiated, was in fact a classic example of a hallowed Pentagon maneuver known as the “bow wave.” When afflicted by rare but irksome intervals of budgetary hardship, the services launch research-and-development projects, initially modest in cost, that lock in commitments to massive spending down the road. A post-Vietnam downturn had spawned the B-2 bomber and the MX intercontinental missile. Now the post–Cold War drought incubated the F-22 and F-35 fighter programs, not to mention a fantasy-laden Army project, replete with computers and sensors, called Future Combat Systems. The cost of these projects would explode in later years, even when there were no tangible results. The F-22 was canceled early in its planned production run, while the Army project never got off the drawing board. The F-35 program staggers on, with an ultimate budget now projected at $1.5 trillion.

All this was achieved without much sign of a viable enemy, despite hopeful invocations of the Chinese military as a potential “peer competitor.” In any case, steps were being taken to remedy that deficiency. As I have explained before in this magazine, the United States casually violated promises made in the Soviet Union’s dying days not to expand NATO into Eastern Europe — an initiative prompted and certainly exploited by U.S. arms manufacturers smarting from the outbreak of peace and in need of fresh markets. A possible downside to this trend surfaced in 2008, when Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili, an enthusiastic petitioner for NATO membership, provoked hostilities with Russia in expectation, reportedly encouraged by Vice President Cheney, of U.S. military support. “Misha was trying to flip us into a war with Russia,” Bruce P. Jackson, a former Lockheed Martin vice president who had been key to the NATO expansion effort, recently explained to me. President Bush proved reluctant to blow up the world on behalf of his erstwhile protégé, and Saakashvili was left to his fate.

Initially, the Obama Administration appeared disposed to warmer relations with Moscow. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton presented her Russian counterpart with a “reset” button. According to Vali Nasr, a former State Department official, the new direction was largely prompted by a desire to gain Russian cooperation for tougher sanctions against Iran. In pursuit of this goal, Nasr later wrote,

Obama stopped talking about democracy and human rights in Russia . . . abandoned any thought of expanding NATO farther eastward, [and] washed his hands of the missile defense shield that had been planned for Europe.

These amicable gestures also extended to a 2010 nuclear-arms-control agreement. New START, as it was called, cut the number of strategic nuclear-missile launchers deployed by either side and limited the number of warheads to 1,550. Commendable as this might seem, there was less to the agreement than met the eye. The treaty reduced the number of deployed Minuteman ICBMs from 450 to 400, along with the same quantity of deployed warheads. Yet this slimmed-down complement of missiles, constituting only part of our nuclear arsenal, still represents eight thousand times the explosive force meted out at Hiroshima. The fifty missiles taken out of service were by no means destroyed, merely stored away against the day when they might be needed, in which case they could be reloaded in their old silos — which would be kept “warm,” ready for reuse.

In fact, this modest effort at trimming the nuclear arsenal came at a high price, which we will be paying for many years to come. As the administration struggled to gain ratification for the treaty, key Republicans, led by Senator Jon Kyl of Arizona, demanded a commitment to the “modernization” of our nuclear forces. This clashed somewhat with Obama’s 2009 pledge to take “concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons.” Nonetheless, he caved and accepted the trade-off. Though the president protested that he was merely taking steps to maintain and secure the existing nuclear arsenal, modernization turned out to mean the wholesale replacement of almost every component of the force with new weapons, and at vast cost.

The Navy has therefore been promised a fleet of twelve ballistic-missile-launching nuclear submarines, loaded with newly developed missiles, at an estimated price of $100 billion. The Air Force will acquire 642 new ICBMs at a supposed cost of $85 billion (a price tag that will, like that of the naval program, inevitably increase). In addition, the Air Force is getting a long-range nuclear bomber, the cost of which it has brazenly classified with the excuse that such details would reveal technical secrets to the enemy. The shopping list also includes several nuclear warheads that are essentially new designs. Meanwhile, command-and-control systems are being developed for an array of satellites (costing up to $1 billion each), whose purpose is to make the business of fighting a nuclear war more manageable.

Those new warheads have allowed the nuclear laboratories (better described as weapons factories) to elbow their way to the trough. Thus the Los Alamos lab in New Mexico plans to expand its facility for producing plutonium “pits” — the fissile core at the heart of a nuclear weapon. Instead of an annual total of ten such pits, Los Alamos now plans to manufacture eighty, at a cost of some $3 billion. This is despite the fact that the United States has roughly 15,000 pits in storage, most of which will be in working order for another century. In a fine example of the pervasive power of the military–industrial complex, Tom Udall of New Mexico, among the most liberal members of the Senate, has felt it necessary to support this inane scheme.

Reliable estimates indicate that “modernization” will ultimately deplete the public purse by $1 trillion. Justifying such spending might have been tough in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet collapse. But times have changed. “We are investing in the technologies that are most relevant to Russia’s provocations,” Brian McKeon, principal deputy undersecretary for policy at the Department of Defense, told Congress in December 2015. In other words, Moscow has resumed its customary role as budget prop and bogeyman — and one with a modernization plan of its own.

On the face of it, the Russians have plenty to modernize. American bomber pilots “need around two hundred hours of flight training a year in order to remain proficient in everything from takeoff to landing to flying the plane,” Bruce Blair told me. “Back in the Nineties, all the Russian pilots were receiving just ten hours of flight training per year. The last time I checked, they were up to eighty or ninety hours.” Blair also cited the Russian deployment of mobile early-warning radars around the borders to compensate for the “drastic decline of their missile-attack early-warning system over the past two decades. They have not yet managed to put up a satellite network.”

True, the Russians have been digging underground bunkers for their military and civilian leadership, including one to house the general staff at their wartime headquarters south of Moscow. They are developing a big intercontinental ballistic missile, the RS-28 Sarmat, and another missile, the Bulava, for a new class of submarine. They are also reported to be designing a nuclear-armed underwater drone, allegedly capable of zipping across the ocean and exploding in an American harbor. You could even argue, as Blair does, that the “operational posture” of the Russian military, which essentially collapsed after 1989, has “been fixed, more or less.”

A Russian military “more or less” back in working order doesn’t sound much like an existential threat, nor like one in any shape to “erode the principled international order.” That has not deterred our military leadership from scaremongering rhetoric, as typified by Philip Breedlove, who stepped down as NATO’s commander in May. Breedlove spent much of his three-year tenure issuing volleys of alarmist pronouncements. On various occasions throughout the Ukrainian conflict, he reported that 40,000 Russian troops were on that nation’s border, poised to invade; that regular Russian army units were operating inside Ukraine; that international observers were reporting columns of Russian troops and heavy weapons entering Ukraine. These claims proved to be exaggerated or completely false. Yet Breedlove continued to hit the panic button. “What is clear,” he told Washington reporters in February 2015, “is that right now, it is not getting better. It is getting worse every day.”

In reality, the fighting had almost completely died down at that point. There was still no sign of the armored Russian invaders Breedlove had unblushingly described. This in no way fazed the general, whose off-duty relaxation runs to leather-clad biker jaunts. His private emails, a portion of which were pilfered and released by a hacker organization called DC Leaks (rapidly and inevitably billed as a Kremlin tool), revealed him to be irritated by Obama’s dovishness and eager to pressure the White House for a change of policy. “I think POTUS sees us as a threat that must be minimized,” he complained to a Washington friend in a 2014 email.

Breedlove’s spurious claims, which were echoed by the U.S. Army commander in Europe, Lieutenant General Ben Hodges, reportedly caused considerable agitation in Berlin, where officials let it be known that they considered such assertions “dangerous propaganda” without any foundation in fact. Der Spiegel, citing sources in Washington, insisted that such statements were by no means off the cuff, but had clearance from the Pentagon and White House. The aim, according to William Drozdiak, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on the United States and Europe, was to “goad the Europeans into jacking up defense spending” — and the campaign seems to have worked. Several NATO members, including Germany, have now begun raising their defense spending to the levels demanded by the United States.

Russian actions, when interpreted as threateningly aggressive, have been a boon to the defense establishment. But talking up Russian capabilities is no less important for nurturing defense budgets in the long term — in case the Kremlin’s foreign policy should take on an inconveniently peaceful turn. So, just as those U.S. generals returned home from a desolate Russia in the mid-1950s convinced that Soviet weapons makers were about to challenge American technical superiority, Russian weapons are today receiving glowing reviews from U.S. military leaders.

Last June, for example, Vice Admiral James Foggo, commander of the Sixth Fleet, told The National Interest that the Russians had upped their game on submarine warfare. He singled out for praise the Severodvinsk, a 13,800-ton behemoth. Foggo also noted that the Russians were “building a number of stealthy hybrid diesel-electric submarines and deploying them around the theatre.” In the same article, Alarik Fritz, a senior official with the Center for Naval Analyses and an adviser to Foggo, described these hybrid vessels as some of the most dangerous threats faced by the U.S. Navy: “They’re a concern for us and they’re highly capable — and they’re a very agile tool of the Russian military.”

A closer look reveals something less impressive. The sinister-sounding description “hybrid diesel-electric” refers to a submarine equipped with a small nuclear reactor that is used to power up the electric batteries that drive the boat while it is underwater. (On the surface, it relies on diesel power.) Despite the admiral’s casual reference to “a number” of such boats, the Russians have built just one, the Sarov. It was laid down in 1988 and entered service in 2008, after which they apparently decided to build no more. In any case, the design concept sounds strange — as the batteries need topping up, the reactor, described by engineers as a “nuclear teakettle,” is switched on and off. This would be a cumbersome and noisy process, the opposite of stealthy. In any event, there is little sign of a surge in Russian submarine building, which seems to be proceeding very, very slowly. The dreaded Severodvinsk, laid down in 1993, took twenty-one years to be built and enter active service. The Sarov, that “very agile tool” of the Evil Empire, took twenty years.

Similar distortion proliferates in depictions of the Russian and, for that matter, the Chinese air force. (China has yet to be raised to “existential” threat status — maybe because we owe them so much money.) Air Superiority 2030 Flight Plan, published by the USAF this year, asserts that the service’s “projected force structure in 2030 is not capable of fighting and winning against [the expected] array of potential adversary capabilities.” Unsurprisingly, this gloomy forecast is followed by an urgent plea for more money. In contrast, Pierre Sprey, who may certainly be considered an authority on fighter design, observes that even the latest Russian fighters are “huge, awfully short-ranged, and relatively unmaneuverable, except at low speeds — which is good for air shows and nothing else. Their ‘latest’ models are basically the same old machines, such as the MiG-29, which has been around for years, with a few trendy add-ons. But they’ve realized that you can sell more airplanes abroad if you change the number, so the MiG-29 has become the MiG-35, and so on.”

Needless to say, Russia’s land forces are being accorded a status no less ominous than its subs and planes. “The performance of Russian artillery in Ukraine,” according to Robert Scales, a retired Army general who is esteemed by many of his peers as a military intellectual, “strongly demonstrates that, over the past two decades, the Russians have gotten a technological jump on us.” The Russians’ T-14 Armata tank is similarly hailed in the defense press as a “source of major concern for Western armies.”

In one sense, the new Red Scare has had the desired and entirely predictable result. Defense spending, though hurt by troop wind-downs in Iraq and Afghanistan, is now exhibiting renewed vigor. Introducing its upcoming $583 billion budget in 2016, the Pentagon specifically cited “Russian aggression” as a rationale for spending. NATO allies have meanwhile pledged to increase their defense spending to 2 percent of GDP.

Yet despite all the rhetoric, practical responses to the “existential threat” have been curiously modest. Even with 480,000 troops, the U.S. Army generates surprisingly little fighting power. According to its chief of staff, this force is hard-pressed to field more than a third of its “ready” 4,500-man brigades, overwhelmingly light infantry, that can deploy and fight in less than a month. “These are paltry numbers for a force that approaches nearly a half-million,” Douglas Macgregor, a former colonel and pungent commentator on defense topics, wrote me recently. To achieve “this stellar result,” added Macgregor, the U.S. Army has eleven four-star generals scattered throughout the world.

A loudly proclaimed plan to bolster NATO’s eastern defenses against those aggressive Russians has turned out to mean sending a battalion — 700 troops! — to Poland and each of the allegedly threatened Baltic republics. In addition, the United States will rotate one armored brigade into and out of Eastern Europe. Aerial reinforcements to the Baltics have been similarly miserly: small contingents of fighters deployed for limited periods before returning home.

It is not as if the military lacks sufficient cash. The Army budget alone, some $150 billion, is more than twice Russia’s spending for the entire armed forces. The ratios for the other services are similarly unbalanced. The answer would seem to lie in the military’s priorities, thanks to which actual defense needs take second place to more urgent concerns, such as the perennial interservice battle for budget share, as well as the care and feeding of defense contractors (who will doubtless employ all those four-star generals once they retire).

This approach, of course, generates a staggering amount of waste. Many of the headline scandals, such as the $200 million F-35 fighter that could not fly within twenty-five miles of a thunderstorm, have become notorious — but the list is long. The Army in particular has spawned an impressive list of procurement projects, including helicopters, radios, and armored troop carriers, that have come to nothing. The Future Combat Systems referred to above is said to have been launched by Army chief of staff General Eric Shinseki as a kind of preemptive strike on the taxpayer’s wallet. “If I don’t buy something new,” he reportedly declared, “no one on the Hill will believe that the U.S. Army is changing.” The project ultimately absorbed $20 billion with nothing whatsoever to show for it.

There would seem to be one major difference between the fine art of threat inflation as practiced during the Cold War and the current approach. In the old days, taxpayers at least got quite a lot for their money, albeit at inflated prices: the 900 ships, the 15,000 planes, and so forth. Things are different today. The so-called global war on terror, though costing more than any American conflict apart from World War II, has been a comparatively lackadaisical affair. Iraq at its height absorbed one fifth the number of troops sent to Vietnam, while Air Force sorties ran at one eighth the earlier level. Though the weapons cost more and more, we produce fewer and fewer of them. For example, the Air Force originally told us they were buying 749 F-22 fighters at a cost of $35 million each. They ended up with 187 planes at $412 million apiece. The trend persists across the services — and sometimes, as in the case of the Army’s Future Combat Systems, no weapons are produced at all.

This may be of comfort to those who worry at the prospect of war. Yet the threat inflation that keeps the wheels turning can carry us toward catastrophe. Among the token vessels deployed to reassure Eastern European NATO countries have been one or two Aegis Destroyers, sent to patrol the Baltic and Black Seas. The missiles they carry are for air defense. Yet the launchers can just as easily carry nuclear or conventional cruise missiles, without any observer being able to tell the difference.

Bruce Blair, who spent years deep underground waiting to launch nuclear missiles and now works to abolish them, foresees frightening consequences. As he told me, “Those destroyers could launch quite a few Tomahawk cruise missiles that can reach all the way to Moscow. You could lay down a pretty severe attack on Russian command-and-control from just a couple of destroyers.” This, he explained, is why the Russians have been aggressively shadowing the ships and buzzing them with fighter planes at very close quarters.

“Now the Russians are putting in a group of attack submarines in order to neutralize those destroyers,” Blair continued. “And we’re putting in a group of P-8 antisubmarine airplanes in the area in order to neutralize the submarines.” Quite apart from the destroyers, he continued, “are the B-2 and B-52 missions we fly over the Poles, which looks like we’re practicing a strategic attack. We fly them into Europe as shows of reassurance. We’re in a low-grade nuclear escalation that’s not even necessarily apparent to ourselves.” Excepting a few scattered individuals in intelligence and the State Department, he continued, “so few people are aware of what we’re getting into with the Russians.” Nobody is paying attention on the National Security Council, Blair said, and he added: “No one at Defense.”