The Letters of Lewis H. Lapham and Henry A. Kissinger

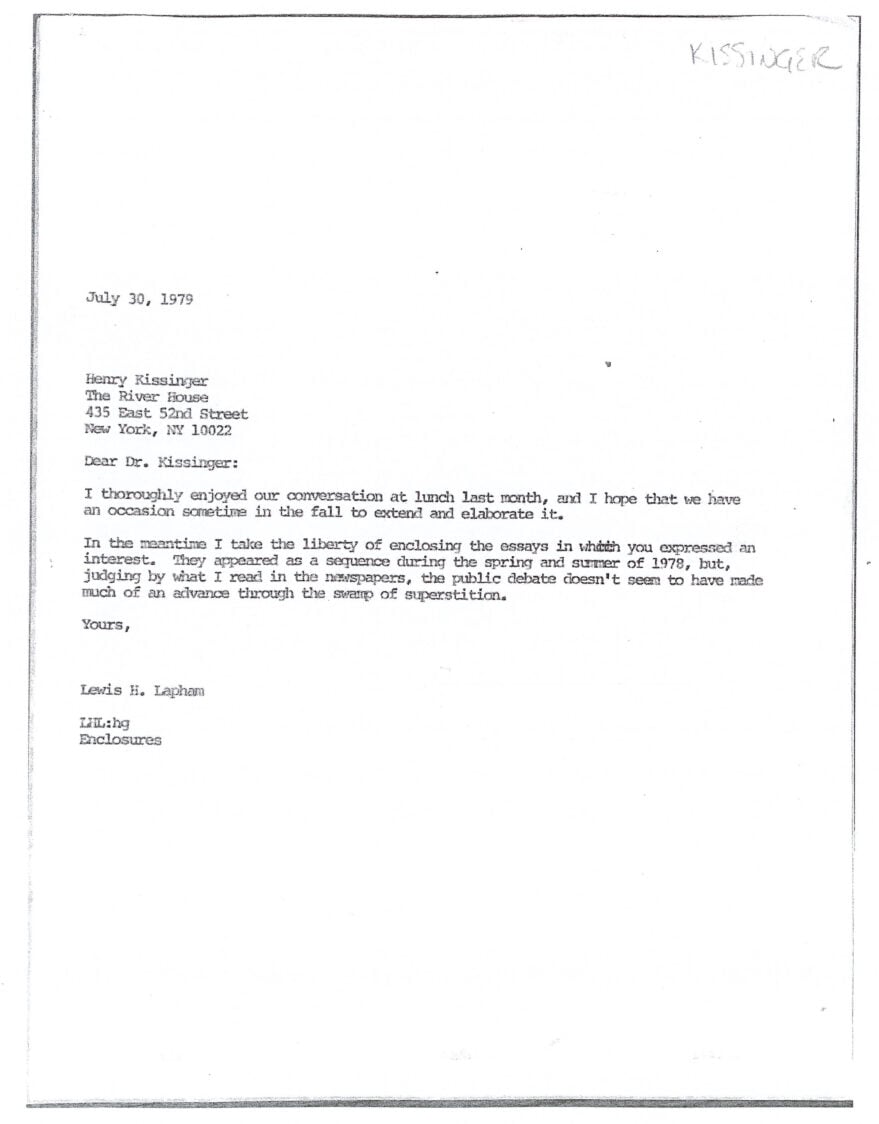

July 30, 1979

Dear Dr. Kissinger:

I thoroughly enjoyed our conversation at lunch last month, and I hope that we have an occasion sometime in the fall to extend and elaborate it.

In the meantime I take the liberty of enclosing the essays in which you expressed an interest. They appeared as a sequence during the spring and summer of 1978, but, judging by what I read in the newspapers, the public debate doesn’t seem to have made much of an advance through the swamp of superstition.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

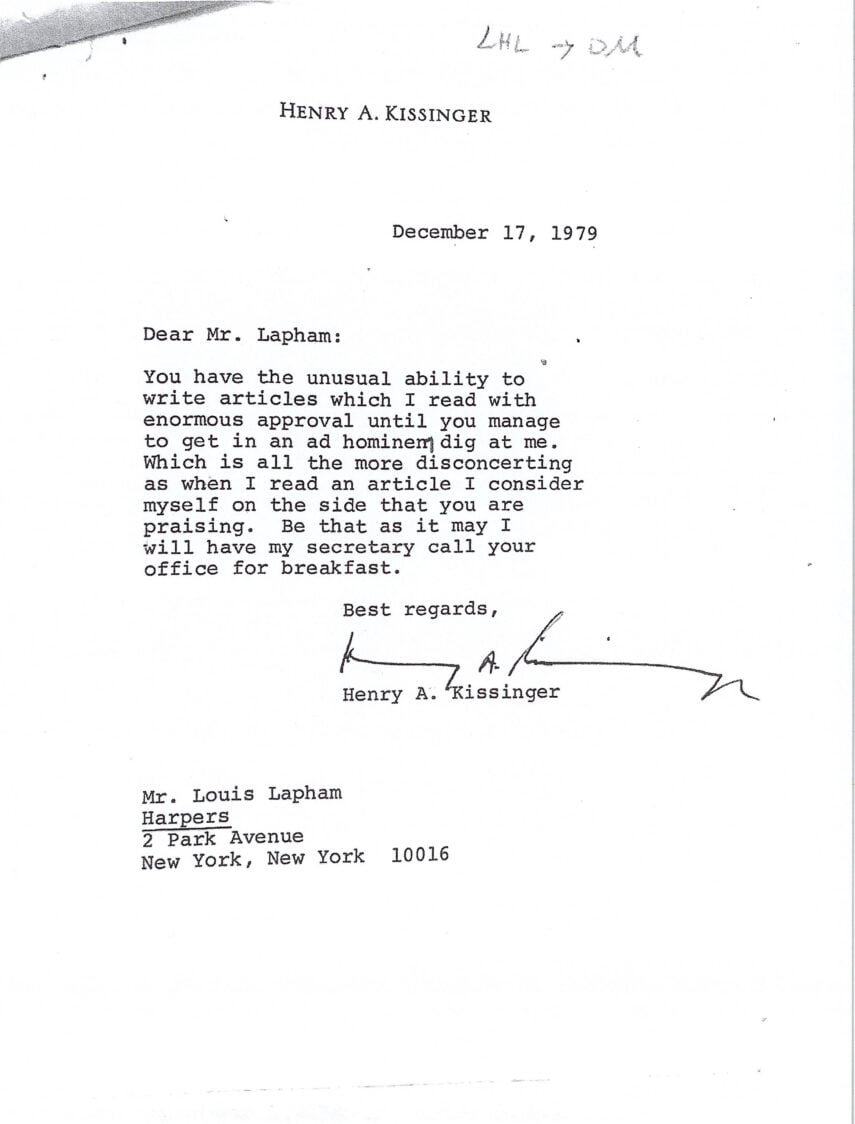

December 17, 1979

Dear Mr. Lapham:

You have the unusual ability to write articles which I read with enormous approval until you manage to get in an ad hominem dig at me. Which is all the more disconcerting as when I read an article I consider myself on the side that you are praising. Be that as it may I will have my secretary call your office for breakfast.

Best regards,

Henry A. Kissinger

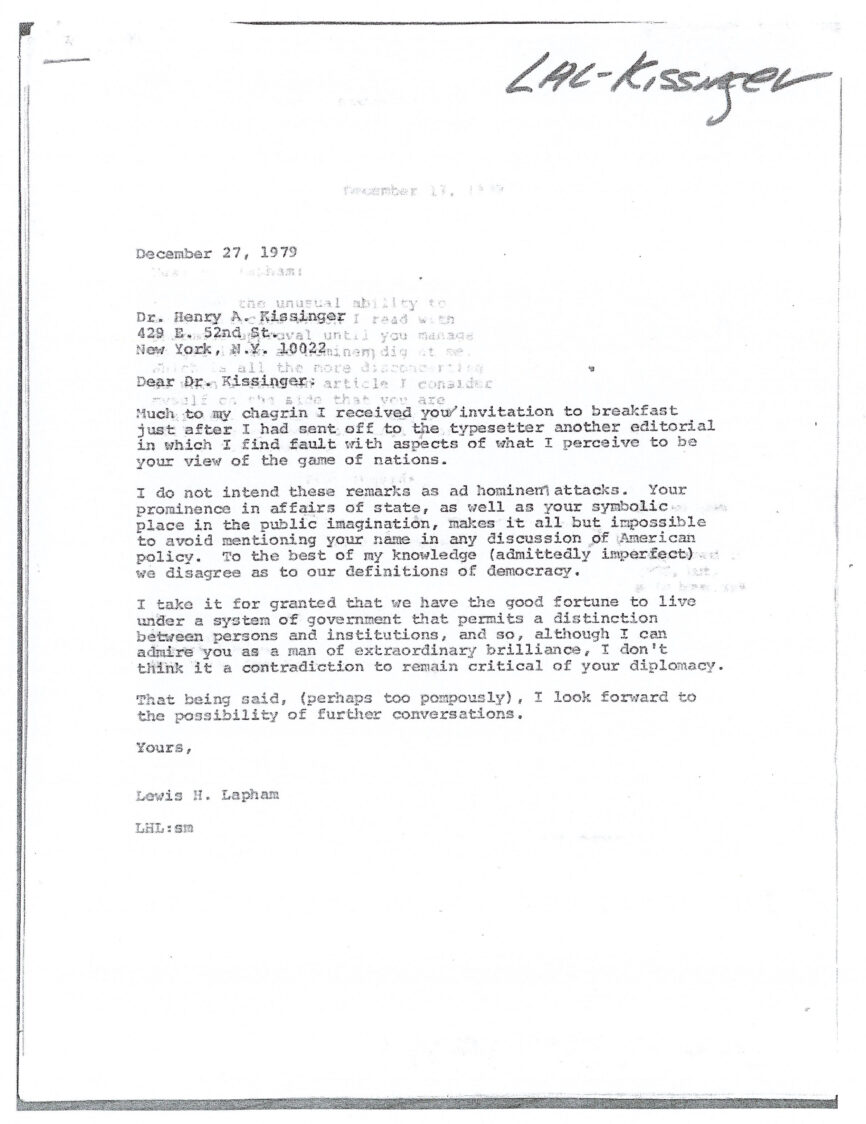

December 27, 1979

Dear Dr. Kissinger:

Much to my chagrin I received your invitation to breakfast just after I had sent off to the typesetter another editorial in which I find fault with aspects of what I perceive to be your view of the game of nations.

I do not intend these remarks as ad hominem attacks. Your prominence in affairs of state, as well as your symbolic place in the public imagination, makes it all but impossible to avoid mentioning your name in any discussion of American policy. To the best of my knowledge (admittedly imperfect) we disagree as to our definitions of democracy.

I take it for granted that we have the good fortune to live under a system of government that permits a distinction between persons and institutions, and so, although I can admire you as a man of extraordinary brilliance, I don’t think it a contradiction to remain critical of your diplomacy.

That being said, (perhaps too pompously), I look forward to the possibility of further conversations.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

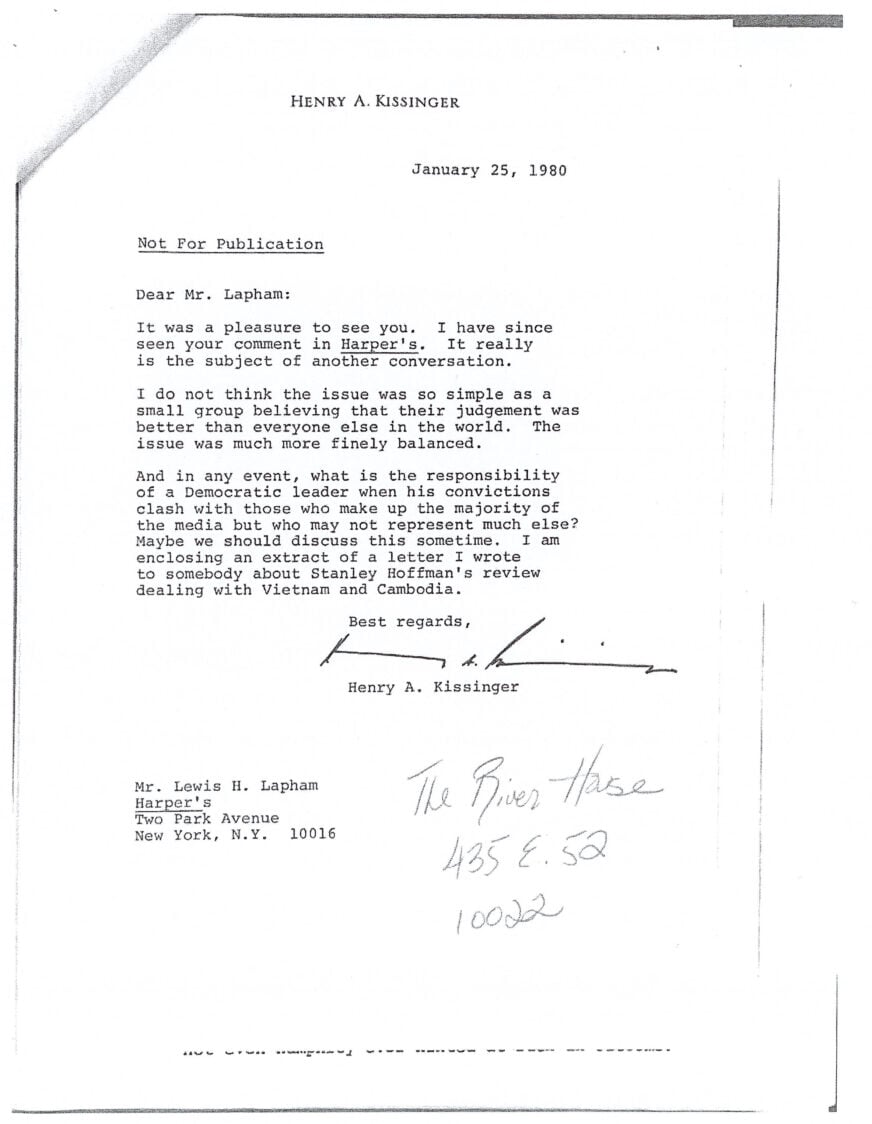

January 25, 1980

Dear Mr. Lapham:

It was a pleasure to see you. I have since seen your comment in Harper’s. It really is the subject of another conversation.

I do not think the issue was so simple as a small group believing that their judgement was better than everyone else in the world. The issue was much more finely balanced.

And in any event, what is the responsibility of a Democratic leader when his convictions clash with those who make up the majority of the media but who may not represent much else? Maybe we should discuss this sometime. I am enclosing an extract of a letter I wrote to somebody about Stanley Hoffman’s review dealing with Vietnam and Cambodia.

Best regards,

Henry A. Kissinger

Stanley has written an incisive, occasionally brilliant exposition of the opposing philosophical position. As do many of his writings, it suffers from pushing sensible arguments to absurd conclusions. Certainly if everything is linked to everything else, flexibility is lost; but so it is when nothing is linked. Similarly Stanley hints darkly that in my account of SALT, I leave out issues such as silo dimensions with respect to which our negotiating methods later led to criticisms. This is in fact fully covered (on pp. 1217 ff.); it was, moreover, a subject negotiated in regular channels and not in the Brezhnev-Nixon “backchannel.” Nor is it true, as Stanley alleges, that I blame the military—or at any rate everyone but myself—for the failure of the Laos operation. On the contrary, I point out (on p. 1111) that the basic mistake was to seek decisive results with insufficient forces, “for which all senior officials, including myself, must bear the responsibility.”

But given the length of the book, even a less biased reviewer than Stanley could miss such esoteric fine points, which are in any case more significant to the author than to the reader. That part of the review, one-sided as it is, is a tour de force.

When Stanley reaches Vietnam, however, he loses any perspective, and on the subject of Cambodia he stoops to endorsing Shawcross’s tawdry personal attack which amounts to a kind of McCarthyism of the left.

With respect to Vietnam, Stanley never tires of stressing the hopelessness of our situation. He insists now that no “honorable” outcome was ever possible. Thus we presumably should have accepted the only terms available before October 8, 1972: connivance in the overthrow of an allied government and the unconditional withdrawal of our forces on a short deadline without even a cease-fire for the south Vietnamese during that process. I have done no research on Stanley’s position during that period; I do know that none of the so-called opponents of the war advocated such a course. McGovern came closest to it but even he talked of longer deadlines and a different kind of coalition government. Can anyone believe that Nixon was elected to accomplish unconditional surrender when he and Wallace obtained 56 percent of the vote and not even Humphrey ever hinted at such an outcome?

In fact a fair presentation would grant that Nixon went far beyond what his record or his pronouncements might have led anyone to expect. I have shown that by August 1969 we had carried out the minority Democratic platform of 1968: in other words we had already exceeded the official programs of both parties. We were then urged to offer a cease-fire; this was accomplished by 1970. After that the responsible critics shifted to proposals for a withdrawal deadline and coalition government–which they never presented as the sort of capitulation Stanley seems now to advocate, but rather as a “balance” of political forces with the Communists in a minority position. A true coalition government was a non-starter, as I have shown at perhaps excruciating length. What Hanoi wanted was a Communist government; and in its absence Hanoi rejected even a withdrawal deadline. In fact, we eventually accepted every proposal of the anti-war movement except the destruction of an allied government that our predecessors had established and the turnover of tens of millions that had relied on us to Communist rule.

Stanley shows not the slightest understanding for the dilemma of a government responsible for the fate of many other nations in extricating 540,000 Americans and over 100,000 foreign troops from a war we did not start. One would never know from his argument that we in fact succeeded in about the same time it took de Gaulle to get France out of Algeria. So what exactly is the criticism about? That Vietnamization was problematical and potentially dangerous? This was recognized early. (See pages 284-286 and the texts of my September 1969 memoranda to Nixon in the notes at pages 1480-1482.) Unconditional surrender, however disguised–and whose difficulty for a serious policymaker no one should underestimate–struck me as dishonorable and disastrous then, and I have not changed my view. One could not read Stanley’s article and learn that we in fact withdrew 150,000 men every year and did in fact end American involvement in the war in a controlled manner–while enduring an unremitting assault led by many who had got us into the mess in the first place.

Similarly Stanley’s attack on the Paris Agreement rests largely on the proposition that we should have known we would never be permitted to enforce it. That perception (never advanced during the war), of course, also implies that surrender was the only realistic option, for no agreement could possibly be negotiated which would be self-enforcing. On that theory, South Korea would long since have disintegrated. What did those who kept urging a negotiated outcome have in mind?

And how is one to reconcile it with a contradictory (not to say hypocritical) strand emerging from Stanley’s analysis: that Thieu was somehow double-crossed, that we not only fought to no purpose but settled too quickly? Thus Stanley “explains” Thieu’s outrage in October 1972 on the ground that even in May 1971 we were still proposing the mutual withdrawal of all outside forces–this despite the flatly contrary documentation of my book. Our May 31, 1971, proposal set a deadline for the withdrawal of US and allied forces; it established precise conditions for a cease-fire; as for the withdrawal of other outside forces, it required only that the Vietnamese parties “discuss” it. This clearly gave Hanoi a veto over the definition of outside forces as well as the timing of their withdrawal. It was a formula for accepting the continued presence of North Vietnamese forces after the withdrawal of ours and after a ceasefire. Hanoi understood this and so did Thieu. In any event the proposal was repeated with Thieu’s approval on October 11, 1971, and publicly by Nixon on January 25, 1972 (where he dropped the reference to “outside forces” altogether) and on May 8, 1972. In short, not even the most biased critic should stoop to denying the plainest fact: that what Hanoi accepted on October 8, 1972 had been on the table for a year and a half (and was of course much more favorable to Thieu than the stance of the anti-war critics, which was coalition government and unilateral withdrawal).

Nor is Stanley’s account of the November-December 1972 negotiations any fairer. By the time they stalemated, the issue was not that Hanoi rejected the sixty-nine changes Thieu had proposed. We were down to one issue, as Le Due Tho admitted. What happened–and is explained at great length in my book–was that Hanoi decided to stonewall any agreement, refusing not only to discuss the one outstanding issue but any of the essential technical protocols as well. By blocking a negotiation Hanoi was gambling that war weariness in America would hand it total victory. Stanley’s assertion that the Christmas bombing killed hundreds simply to give Thieu a psychological lift is false and indecent.

Stanley’s arguments on Vietnam seem to me to suffer from the same horrible self-righteousness which was the bane of our entire debate. Thus he cites my comment about some academic friends as examples of my vindictiveness. But he neglects to describe the incidents to which these comments refer nor my account of my attitude towards the protesters (pp. 299-303) or my efforts to stay in touch with them (pp. 514, 1015-1016); indeed I would hardly have thought these incidents worthy of attention had they not involved men and women who had meant a lot to me. I sought to present the anguish of a tragic process; for Stanley everything is simple and self-evident. No one then in office can claim that no mistakes were made; but the merciless critics will prevent any serious lesson from being learned if they fail to admit that most of their predictions of what would happen in case of a Communist victory turned out to be disastrously wrong.

Where Stanley is one-sided on Vietnam, he goes over the borderline of fair discourse into McCarthyism in his discussion of Cambodia. The essence of McCarthyism is the making of charges impugning the morality of the other side; backing them up with semi-specious documentation (“I hold in my hand here. . .”); and when confronted with contrary evidence simply ignoring or better still reinterpreting it. In this sense Shawcross sets the pattern; but Stanley is not absolved, for he quotes his tendentious potboiler as if no other authority existed even though I have marshalled voluminous evidence contradicting it.

Sihanouk was overthrown on March 18 without our foreknowledge; as early as March 20, from Peking, he declared himself on the North Vietnamese side and on March 23 announced the creation of a “liberation army” to overthrow the new Cambodian government. At the end of March the North Vietnamese broke out of their sanctuaries and began to invest all of eastern Cambodia. On April 4 we offered immediate talks on the neutralization of Cambodia–these were turned down. In late April–or four weeks after Sihanouk’s throwing in his lot with the North Vietnamese–we finally took a decision to clean out the santuaries [sic].

How does Stanley handle these incontroverted facts? He mentions none of them. (Not one of the critics has yet deigned to acknowledge our offer of April 4.) He alludes darkly to Nixon’s stated eagerness to do something; to plans of Saigon “the Communists must have known about.” He justifies Hanoi’s actions by our plans; he simply denies that Hanoi could have wanted to occupy Phnom Penh; he takes refuge in a mythical “third force” between Lon Nol and the Khmer Rouge whom we allegedly kept from power.

The facts simply do not support any of these propositions. The threat to Phnom Penh was real, and antedated any American action. Indeed, the reader of the Shawcross book will hardly know of what is perhaps one of the crucial turning points of modern Cambodian history: the wave of North Vietnamese attacks on Cambodian military positions, towns, roads, river and rail communications beginning at the end of March 1970 and continuing for over a month before the American “incursion.” It was this event that spread the fighting to Cambodia; it was this that engulfed the Cambodian armed forces in the Indochina war for the first time. Shawcross has one sentence mentioning that the North Vietnamese moved westward into Cambodia for the allegedly defensive purpose of “securing their lines of communication.” In fact, documents which Shawcross had obtained under the Freedom of Information Act–but failed to use–made clear that by April 21, the North Vietnamese had systematically cut all of the roads, waterways and rail links into Phnom Penh, blocking the highways particularly to the north, east, and south of the city and interrupting traffic on the Mekong River which was the city’s most vital lifeline. These North Vietnamese actions had little to do with “securing their lines of communication” but a great deal to do with strangling the lines of communication of the Cambodian capital.

Stanley then takes refuge in Shawcross’s claim that Khmer Serai units were “launched on a grand scale into Cambodia,” which supposedly provoked the North Vietnamese attacks. What Shawcross omits to mention is that these so-called Khmer Serai totalled a mere 3500 men and the decision to send them was made on April 22–and executed days later–when Phnom Penh was already surrounded by the North Vietnamese and as part of our attempt to prevent the fall of Phnom Penh. It is difficult to see how this act could have provoked the North Vietnamese attacks four weeks earlier.

As for the negotiations on Cambodia, Stanley fails to tell us how we would go about contacting Sihanouk when he had deliberately placed himself in Peking (with which we had no contact) and already declared war on us. During the negotiation of the Paris Agreement on Vietnam, we made a concerted effort for a parallel settlement in Cambodia. We did not, as I shall show in my next volume, insist on the retention of Lon Nol; we sought a coalition between the Cambodian government side (without Lon Nol) and the Khmer Rouge, a coalition that we hoped would be headed by Sihanouk. The Khlner Rouge consistently vetoed all attempts to negotiate on such a basis from 1972 to 1975.

Matters do not improve when Stanley turns to the “secret bombing”. He quotes approvingly General Abrams’s alleged support for the proposition that the bombing drove the North Vietnamese deeper into Cambodia and helped destabilize Sihanouk. In fact, what Abrams “acknowledged” fell far short of that; the words Shawcross quotes, moreover, were spoken by Senator Symington, not by General Abrams–a rather cheap bit of sleight of hand. Shawcross’s other purported documentation on this point is even more fraudulent. He quotes a JCS memo of 1969 that in fact refers to the enemy’s dispersion of supplies, not the spread of fighting as he claims; and he cites a 1969 article by Lon Nol which refers to the increase in numbers of Communist troops in Cambodia as a result of clearing operations in South Vietnam, not to their spreading in Cambodia as a result of our bombing. Even the map in Shawcross’s book shows no change in the location of the sanctuaries between 1969 and 1970. The significant spreading of North Vietnamese troops took place in March-April 1970, after the Cambodian government dared to ask them to leave.

Stanley is no more precise in analyzing the motives for our bombing of the sanctuaries. He suggests that it resulted more from Nixon’s eagerness to loosen old constraints than from the North Vietnamese spring offensive. To reach this conclusion Stanley must suppress incontrovertible facts. To be sure, when we had evidence of an imminent offensive, Nixon ordered me to look into what could be done to “destroy the build-up there.” The inconvenient fact is, however, that we did nothing about it. On the contrary, on February 22, 1969–the day the enemy offensive started–he approved my recommendation that we not engage in bombing of the sanctuaries. Afterwards we waited over three weeks and issued many warnings before ordering one retaliatory blow. Yet Stanley considers Cambodia’s neutrality only “dented” by the North Vietnamese occupation of its territory while we presumably totally violated it by bombing military targets occupied exclusively by the North Vietnamese.

While ascribing total ignorance or depravity to his opponents, Stanley gives no account of the negotiating efforts nor of Hanoi’s intransigence nor admits that the Administration could possibly have had a valid concern on even a minor detail. This is the tragedy of our Vietnam debate. I do not claim omniscience or infallibility. Only our critics do. The conclusion remains inescapable that the anti-war left feels a vested interest in any contorted reasoning that seems to absolve it from its own share of responsibility for the horrendous consequences of the collapse of the non-Communist side, which it so long encouraged.

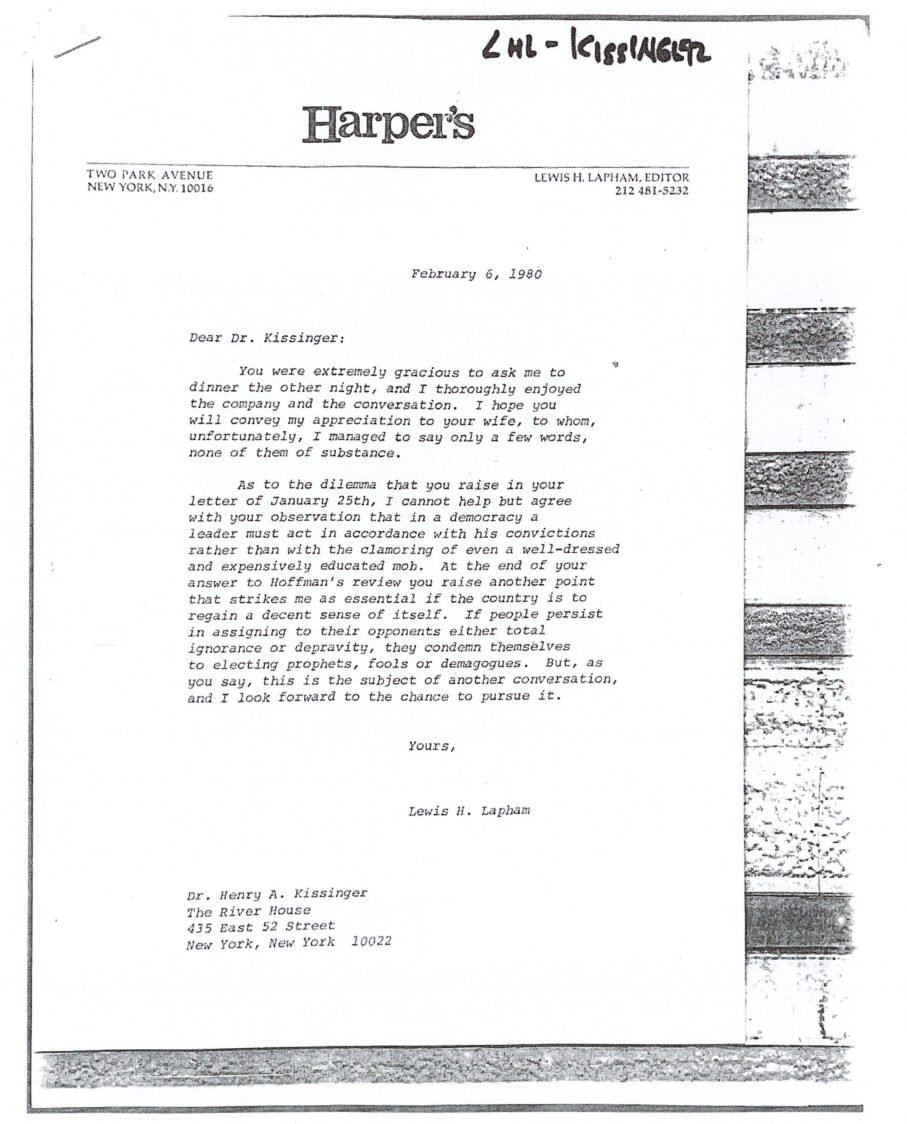

February 6, 1980

Dear Dr. Kissinger:

You were extremely gracious to ask me to dinner the other night, and I thoroughly enjoyed the company and the conversation. I hope you will convey my appreciation to your wife, to whom, unfortunately, I managed to say only a few words, none of them of substance.

As to the dilemma that you raise in your letter of January 25th, I cannot help but agree with your observation that in a democracy a leader must act in accordance with his convictions rather than with the clamoring of even a well-dressed and expensively educated mob. At the end of your answer to Hoffman’s review you raise another point that strikes me as essential if the country is to regain a decent sense of itself. If people persist in assigning to their opponents either total ignorance or depravity, they condemn themselves to electing prophets, fools or demagogues. But, as you say, this is the subject of another conversation, and I look forward to the chance to pursue it.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

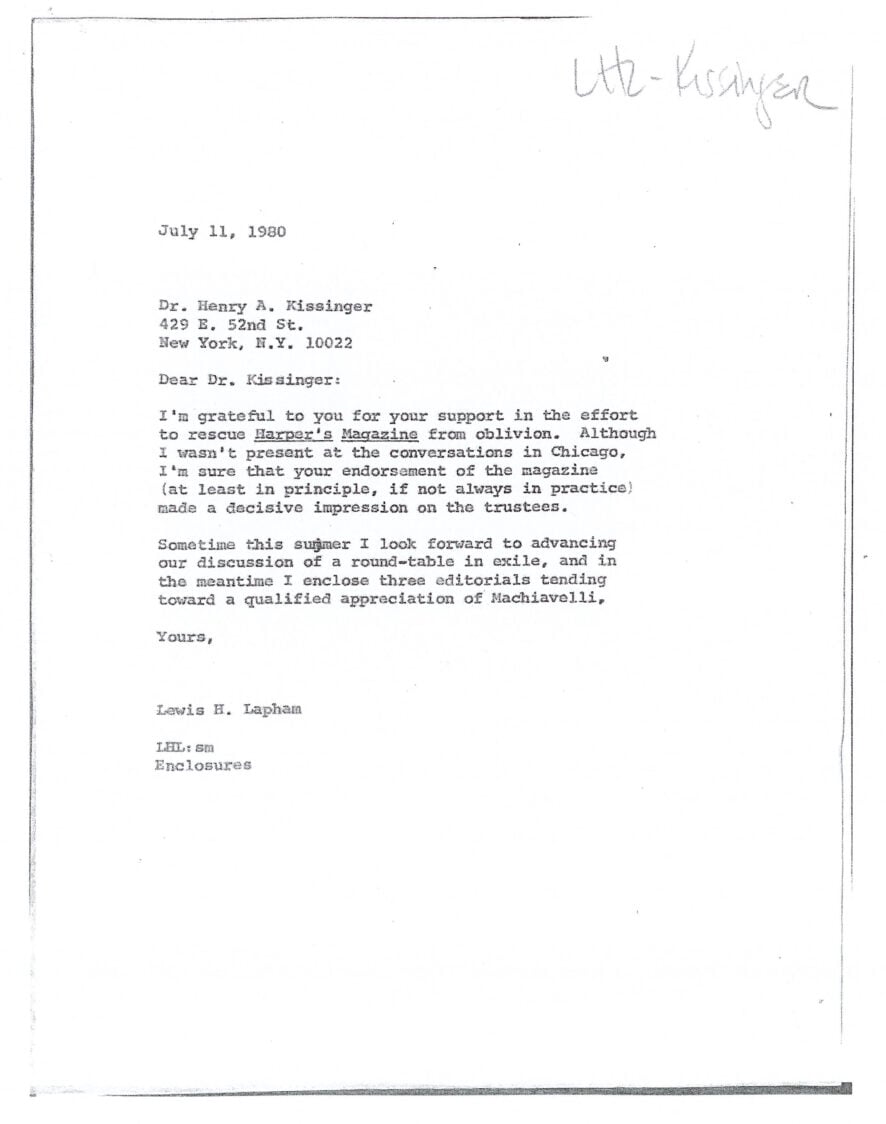

July 11, 1980

Dear Dr. Kissinger,

I’m grateful to you for your support in the effort to rescue Harper’s Magazine from oblivion. Although I wasn’t present at the conversations in Chicago, I’m sure that your endorsement of the magazine (at least in principle, if not always in practice) made a decisive impression on the trustees.

Sometime this summer I look forward to advancing our discussion of a round-table in exile, and in the meantime I enclose three editorials tending toward a qualified appreciation of Machiavelli.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

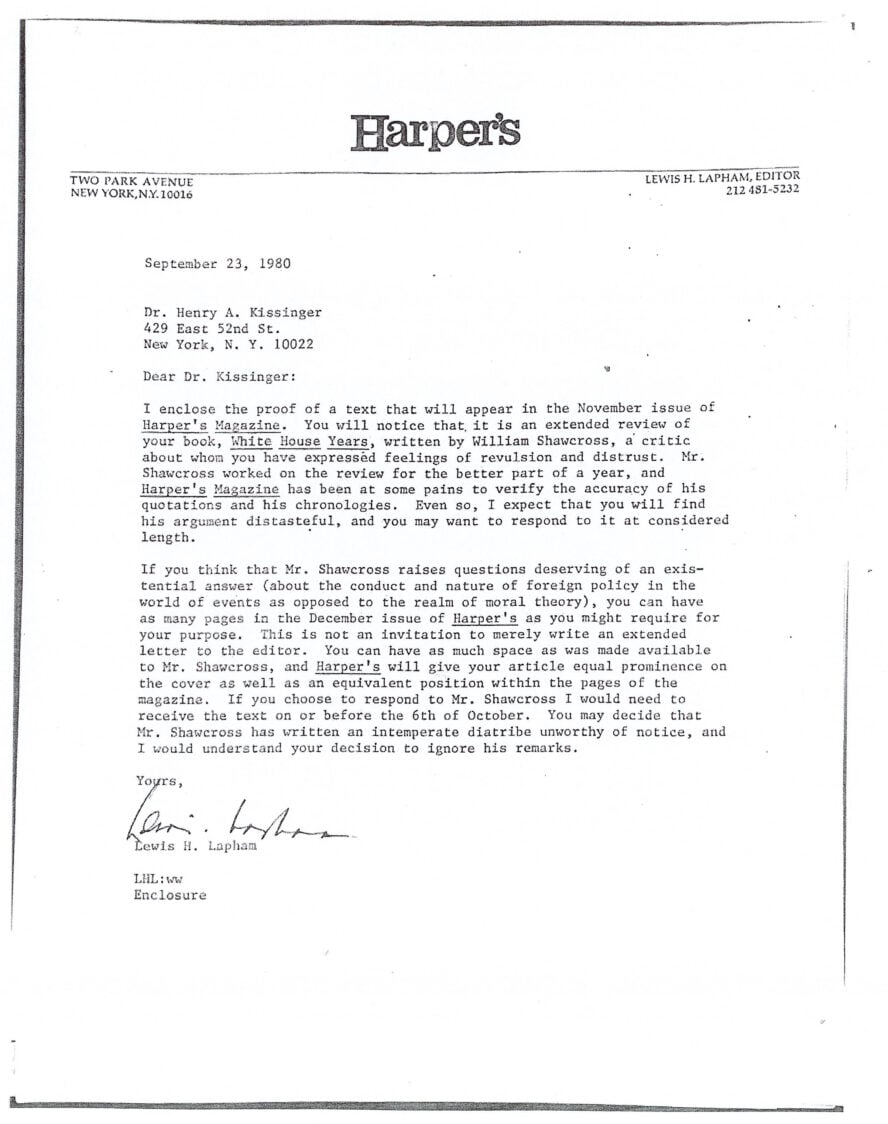

September 23, 1980

I enclose the proof of a text that will appear in the November issue of Harper’s Magazine. [Available here.] You will notice that it is an extended review of your book, White House Years, written by William Shawcross, a critic about whom you have expressed feelings of revulsion and distrust. Mr. Shawcross worked on the review for the better part of a year, and Harper’s Magazine has been at some pains to verify the accuracy of his quotations and his chronologies. Even so, I expect that you will find his argument distasteful, and you may want to respond to it at considered length.

If you think that Mr. Shawcross raises questions deserving of an existential answer (about the conduct and nature of foreign policy in the world of events as opposed to the realm of moral theory), you can have as many pages in the December issue of Harper’s as you might require for your purpose. This is not an invitation to merely write an extended letter to the editor. You can have as much space as was made available to Mr. Shawcross, and Harper’s will give your article equal prominence on the cover as well as an equivalent position within the pages of the magazine. If you choose to respond to Mr. Shawcross I would need to receive the text on or before the 6th of October. You may decide that Mr. Shawcross has written an intemperate diatribe unworthy of notice, and I would understand your decision to ignore his remarks.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

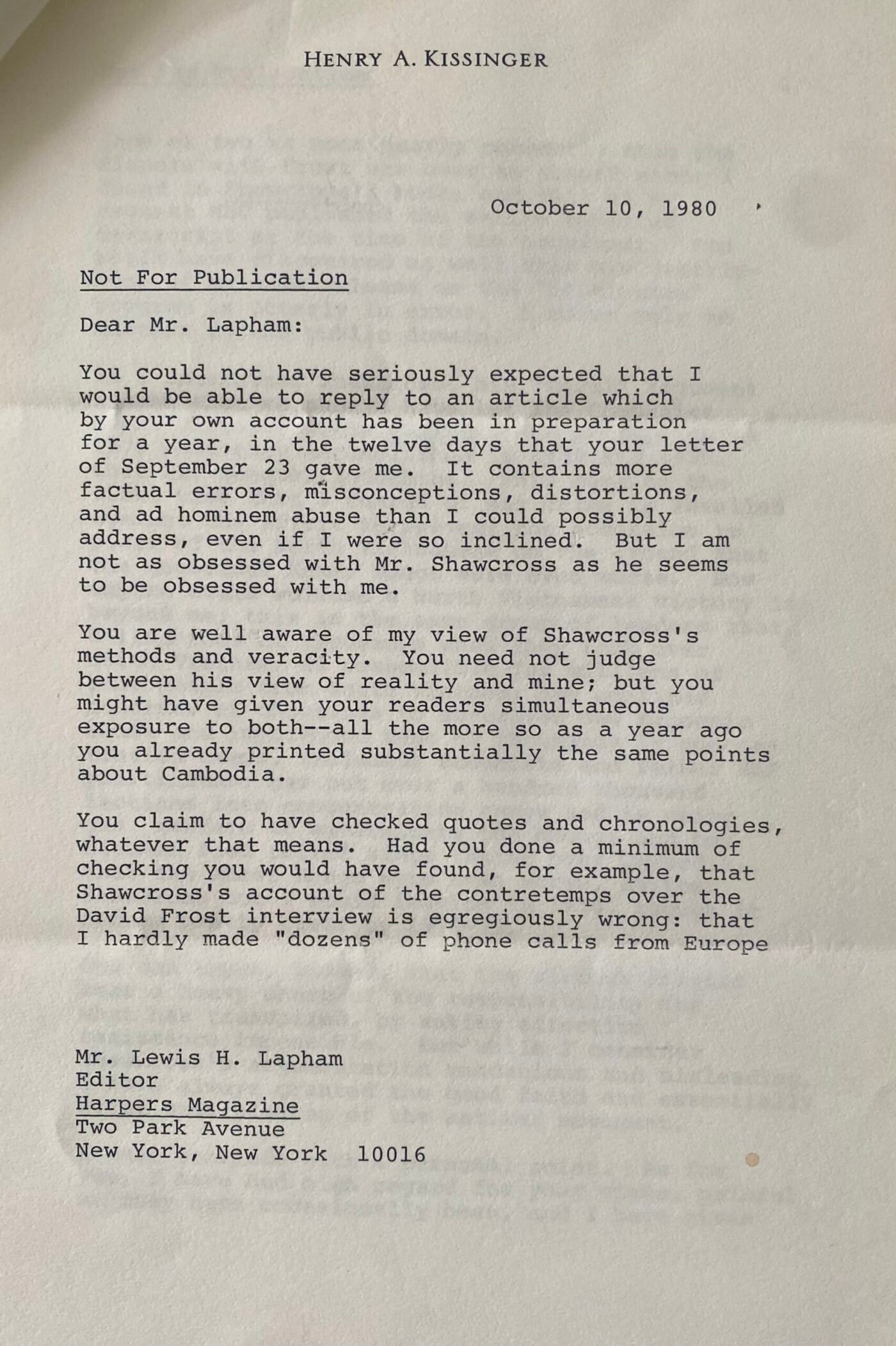

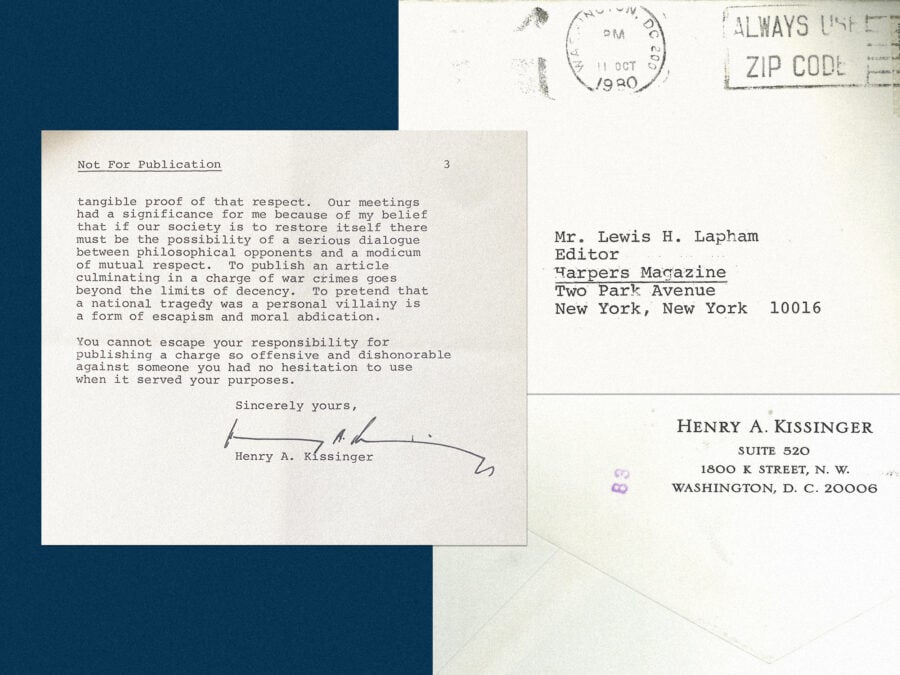

October 10, 1980

Dear Mr. Lapham,

You could not have seriously expected that I would be able to reply to an article which by your own account has been in preparation for a year, in the twelve days that your letter of September 23 gave me. It contains more factual errors, misconceptions, distortions, and ad hominem abuse than I could possibly address, even if I were so inclined. But I am not as obsessed with Mr. Shawcross as he seems to be obsessed with me.

You are well aware of my view of Shawcross’s methods and veracity. You need not judge between his view of reality and mine; but you might have given your readers simultaneous exposure to both–all the more so as a year ago you already printed substantially the same points about Cambodia.

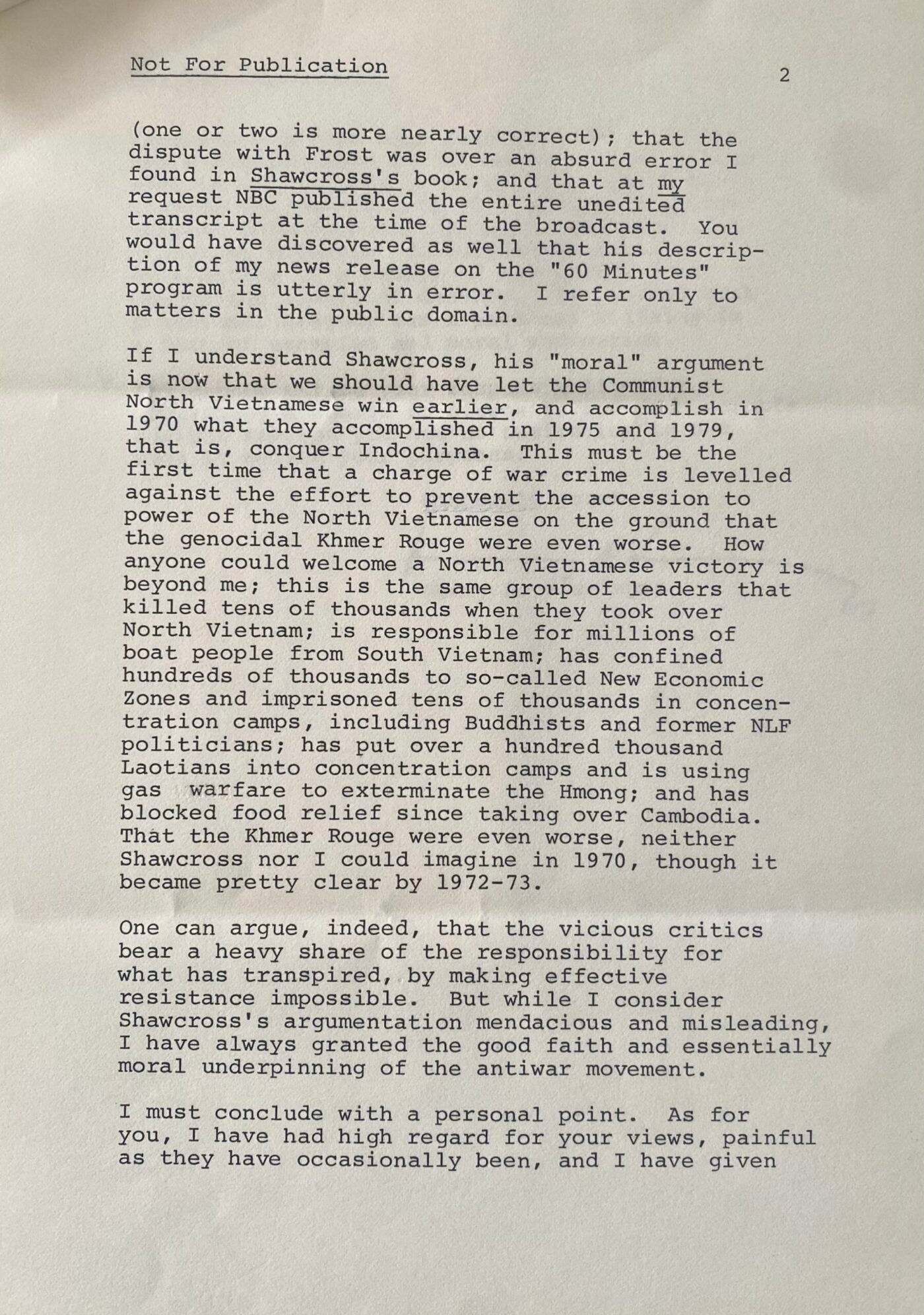

You claim to have checked quotes and chronologies, whatever that means. Had you done a minimum of checking you would have found, for example, that Shawcross’s account of the contretemps over the David Frost interview is egregiously wrong: that I hardly made “dozens” of phone calls from Europe (one or two is more nearly correct); that the dispute with Frost was over an absurd error I found in Shawcross’s book; and that at my request NBC published the entire unedited transcript at the time of the broadcast. You would have discovered as well that his description of my news release on the “60 Minutes” program is utterly in error. I refer only to matters in the public domain.

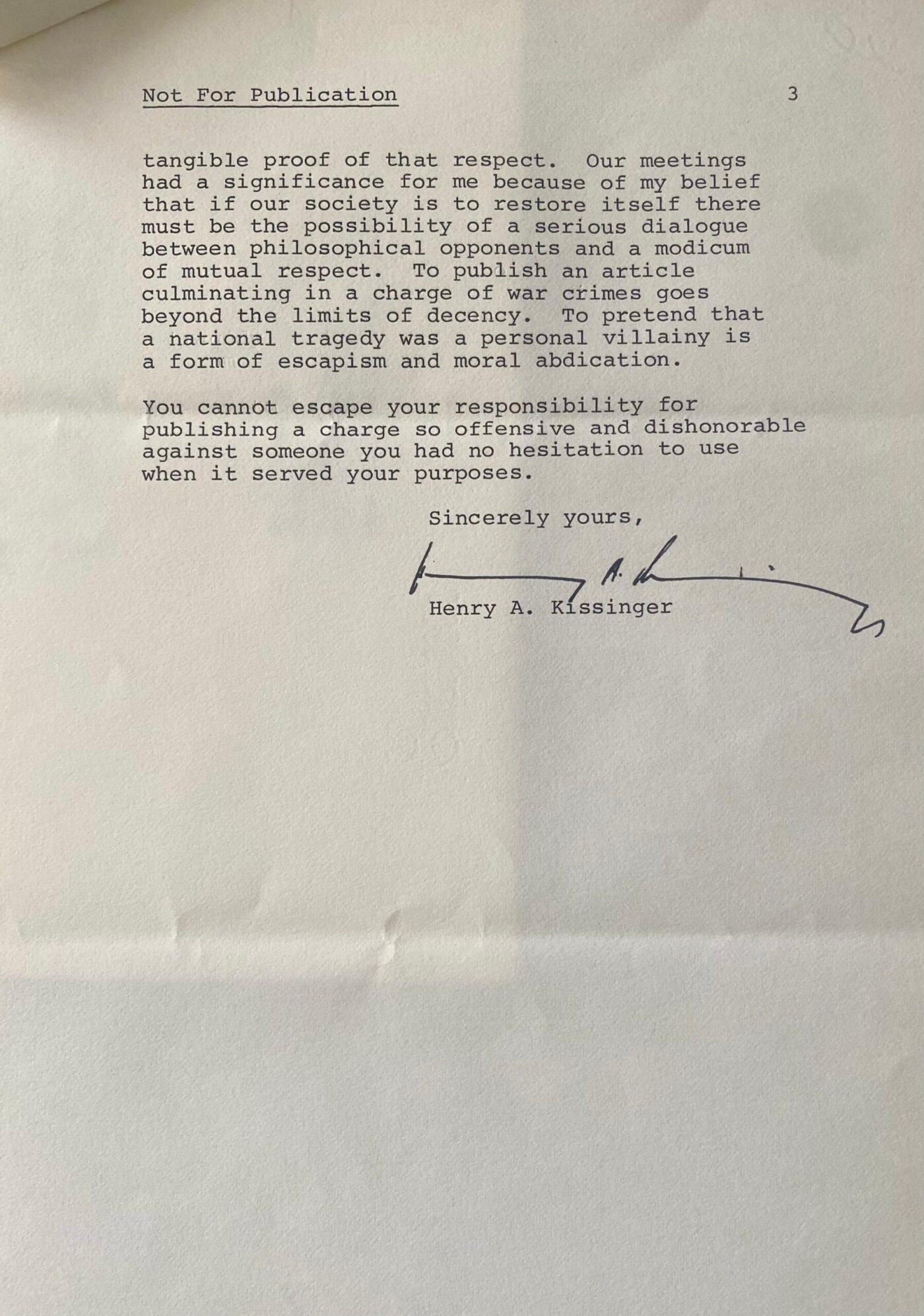

If I understand Shawcross, his “moral” argument is now that we should have let the Communist North Vietnamese win earlier, and accomplish in 1970 what they accomplished in 1975 and 1979, that is, conquer Indochina. This must be the first time that a charge of war crime is levelled against the effort to prevent the accession to power of the North Vietnamese on the ground that the genocidal Khmer Rouge were even worse. How anyone could welcome a North Vietnamese victory is beyond me; this is the same group of leaders that killed tens of thousands when they took over North Vietnam; is responsible for millions of boat people from South Vietnam; has confined hundreds of thousands to so-called New Economic Zones and imprisoned tens of thousands in concentration camps, including Buddhists and former NLF politicians; has put over a hundred thousand Laotians into concentration camps and is using gas warfare to exterminate the Hmong; and has blocked food relief since taking over Cambodia. That the Khmer Rouge were even worse, neither Shawcross nor I could imagine in 1970, though it became pretty clear by 1972-73. One can argue, indeed, that the vicious critics bear a heavy share of the responsibility for what has transpired, by making effective resistance impossible. But while I consider Shawcross’s argumentation mendacious and misleading, I have always granted the good faith and essentially moral underpinning of the antiwar movement. I must conclude with a personal point. As for you, I have had high regard for your views, painful as they have occasionally been, and I have given tangible proof of that respect. Our meetings had a significance for me because of my belief that if our society is to restore itself there must be the possibility of a serious dialogue between philosophical opponents and a modicum of mutual respect. To publish an article culminating in a charge of war crimes goes beyond the limits of decency. To pretend that a national tragedy was a personal villainy is a form of escapism and moral abdication.

You cannot escape your responsibility for publishing a charge so offensive and dishonorable against someone you had no hesitation to use when it served your purposes.

Sincerely yours,

Henry A. Kissinger

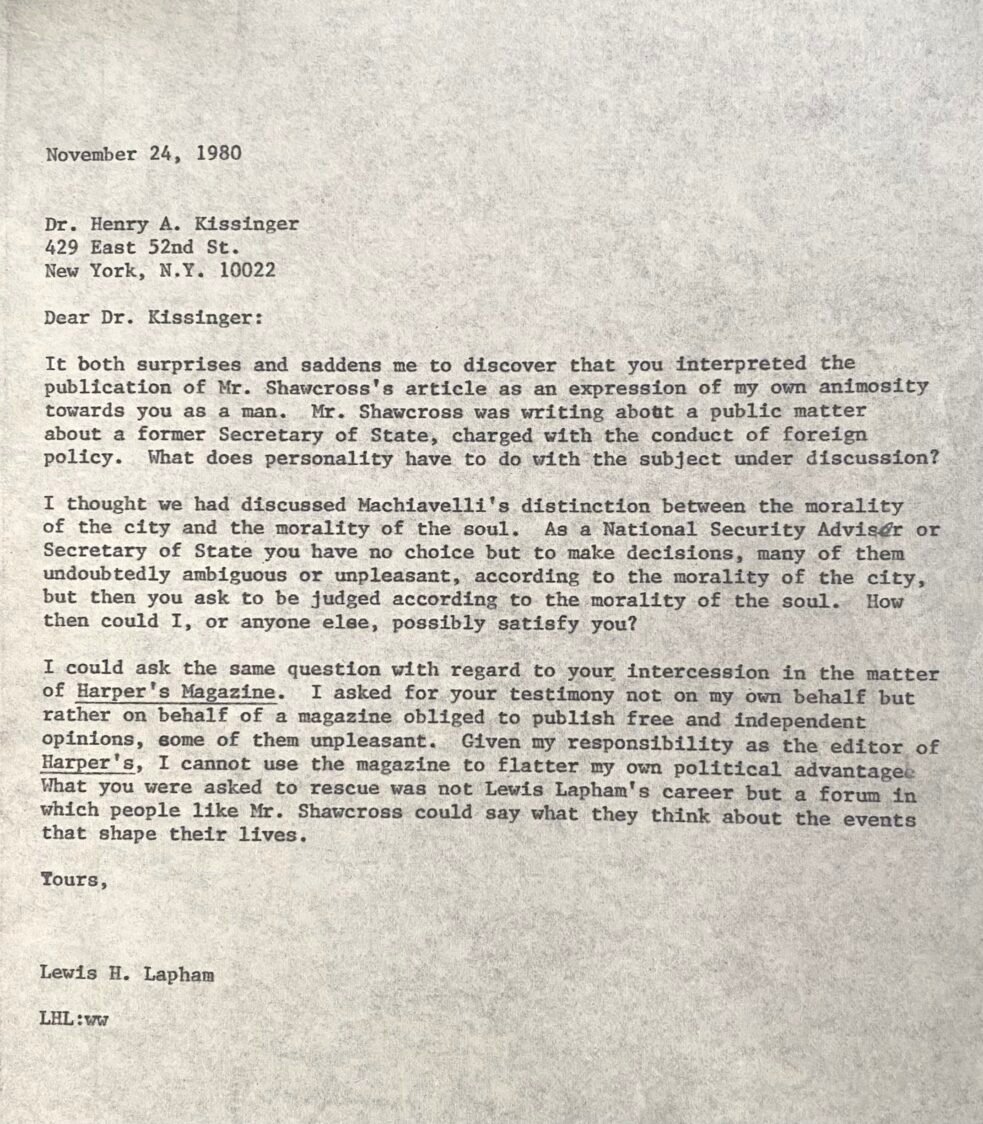

November 24, 1980

Dear Dr. Kissinger:

It both surprises and saddens me to discover that you interpreted the publication of Mr. Shawcross’s article as an expression of my own animosity towards you as a man. Mr. Shawcross was writing about a public matter about a former Secretary of State, charged with the conduct of foreign policy. What does personality have to do with the subject under discussion?

I thought we had discussed Machiavelli’s distinction between the morality of the city and the morality of the soul. As a National Security Advisor or Secretary of State you have no choice but to make decisions, many of them undoubtedly ambiguous or unpleasant, according to the morality of the city, but then you ask to be judged according to the morality of the soul. How then could I, or anyone else, possibly satisfy you?

I could ask the same question with regard to your intercession in the matter of Harper’s Magazine. I asked for your testimony not on my own behalf but rather on behalf of a magazine obliged to publish free and independent opinions, some of them unpleasant. Given my responsibility as the editor of Harper’s I cannot use the magazine to flatter my own political advantage. What you were asked to rescue was not Lewis Lapham’s career but a forum in which people like Mr. Shawcross could say what they think about the events that shape their lives.

Yours,

Lewis H. Lapham

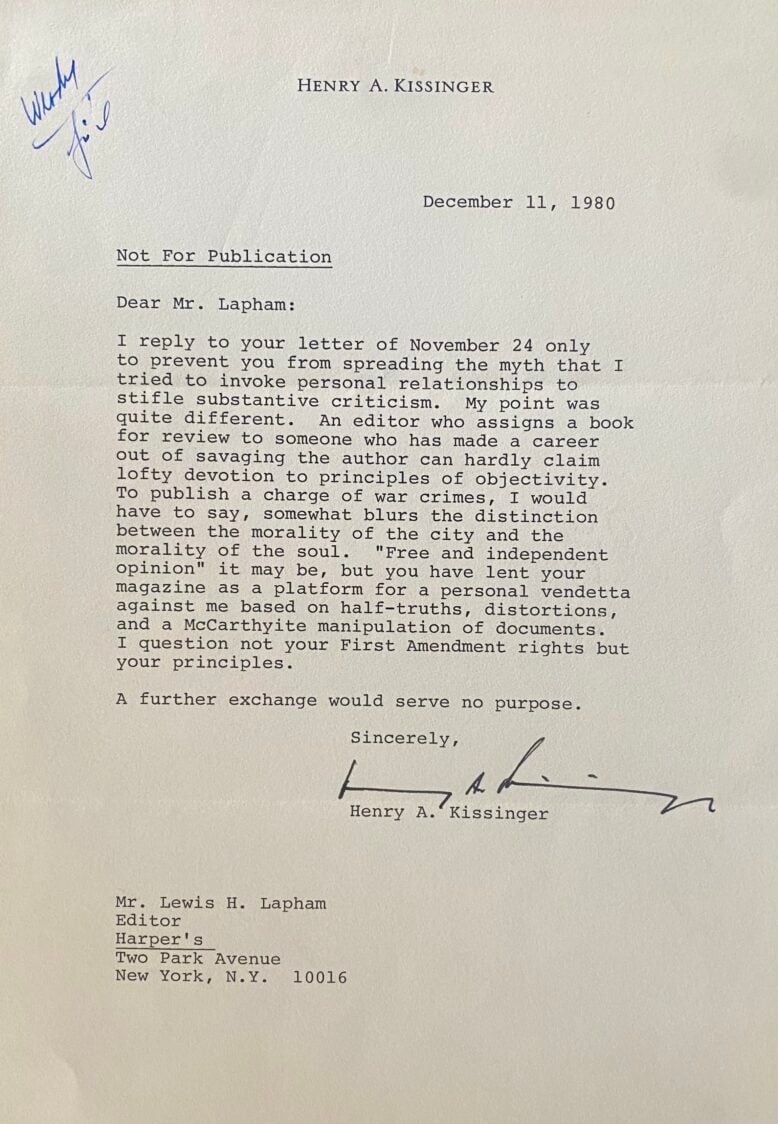

December 11, 1980

Dear Mr. Lapham:

I reply to your letter of November 24 only to prevent you from spreading the myth that I tried to invoke personal relationships to stifle substantive criticism. My point was quite different. An editor who assigns a book for review to someone who has made a career out of savaging the author can hardly claim lofty devotion to principles of objectivity. To publish a charge of war crimes, I would have to say, somewhat blurs the distinction between the morality of the city and the morality of the soul. “Free and independent opinion” it may be, but you have lent your magazine as a platform for a personal vendetta against me based on half-truths, distortions, and a McCarthyite manipulation of documents. I question not your First Amendment rights but your principles.

A further exchange would serve no purpose.

Sincerely,

Henry A. Kissinger

For more on this correspondence, read John R. MacArthur’s Publisher’s Letter in the November 2024 issue here.