One of the things I like about Walmart is that pretty much the nearest neighbor to its Home Office, which is to say the nearest neighbor to the world headquarters of a company that sold more than $400 billion worth of stuff last year, is the world headquarters of Keith’s Body Shop. Over here, you’ve got your basic Fortune 1 company, the Heavyweight Champion of World Capitalism, an outfit with more than 2 million employees — the kind of company that (allegedly) pays more in foreign bribes each year than most make in profits — and over there, you’ve got Keith. He’s just down the way, running his own command center from a one-story corrugated-metal building, the second-biggest business on the block. You fly in from New York or Chicago or Beijing or Berlin and want to negotiate the price you’re going to get for millions and millions of disposable razors, digital cameras, frilly pink baby clothes, cheap flip-flops — that’s here. You want to get that dent in your Camry taken care of — go see Keith.

So last July I went to Bentonville, Arkansas, which is where the Home Office, and Keith, are located, to talk to Walmart about a new initiative to double the amount of local produce the company sells in the United States. Local, for the moment, was being defined as grown and sold within the same state, and Walmart had promised to increase the proportion of local tomatoes and peaches and peppers and watermelons and so on that it sells from about 4.5 percent of its supply to 9 percent by 2015. Which may seem like small numbers until you consider that Walmart sells almost $150 billion worth of groceries a year. Nine percent, hence: a lot of local eggplants.

I had flown to Shreveport and rented a car, thinking I’d drive down through Louisiana, then over and up into Mississippi, and then across Arkansas through the Ozarks to Walmart HQ, spending some time talking to farmers along the way. This turned out to be a route, unsurprisingly, with a lot of Walmarts available for local-produce inspection. At Walmart Supercenter No. 448, a few miles from Shreveport Regional Airport, I bought two local tomatoes ($1.49) and a red T-shirt with america: land of opportunity printed on the front ($5.48). The T-shirt had a tag that told me it had been made in Nicaragua of 100 percent polyester; the tomatoes were less informative, though because I had the Walmart definition of local in mind, I could at least assume that they had been grown in Louisiana. They were the ripest tomato-red they could be, perfect globes, almost like Christmas ornaments. They tasted fine. On my way to the hotel I stopped by the Shreveport Farmers’ Market and bought four much smaller tomatoes ($1.50), cracked and lumpy and cat-faced, streaked with green and smeared with dirt. I thought they tasted better, though not enough better to rule out the possibility that they weren’t better at all, just the beneficiaries of the fact that I’d bought them from a sweet lady who’d picked them herself and, as she bagged them for me, asked me in her sweet bayou accent if I wouldn’t like a little jar of pickled okra, just to try, since I was a stranger to this part of the world.

From Shreveport south, through Cajun country, and then the next day east, past Baton Rouge. The highways, swelling in triple-digit July heat, were dotted with torn-up tire treads, and I made slow progress, unable to resist stopping in Walmarts about every fifty miles or so: Johnny Cash’s 16 Biggest Hits ($5), glazed doughnuts (53¢ each), more local tomatoes ($1.49), a case of Miller High Life ($12.47). In Tickfaw, Louisiana, an hour or so north of New Orleans, I stopped to meet a strawberry grower named Anthony Liuzza. I had reached Liuzza on the recommendation of the Walmart communications team, though Liuzza himself didn’t seem to realize this, that he’d been picked by a public-relations team as a success story. Liuzza is a fifty-five-year-old fourth-generation grower — both his mother’s grandfather and his father’s father had come from Sicily to Louisiana and started growing strawberries on this land — a frank and open guy who has been farming since he graduated from high school, in 1975, and who has been selling to Walmart, happily, for fifteen years.

“We was in a transition, a lot of things was changing at that time with some of our other customers,” he told me, showing me around the property from the elevated vantage of his gigantic white pickup. “Not for the good. So the Walmart thing hit at a perfect time.” The strawberry fields were stripped now — the season was over — but Liuzza had expanded from berries to a much larger operation; he had a whole series of fall fruits and vegetables to sell to Walmart, including cabbage, bell peppers, cucumbers, squash, and tomatoes, and his workers were readying the rows for the new crops. “We was doing direct store deliveries with strawberries at first,” he said. “At that time we was about a twenty-five-acre strawberry farm.” From those twenty-five acres, Liuzza has expanded his fiefdom — now shared with his son, Kevin, and Kevin’s wife, Lizzy — to around 500 acres by trucking his produce to the local Walmart distribution center (known as a DC). As we passed a barn and some prefabricated housing, Liuzza spotted his daughter-in-law, eight months pregnant, talking with a federal inspector sent to survey the living conditions the Liuzzas provide for seasonal workers, and he waved her over.

Lizzy got in the truck, and we headed over to another of the family’s plots, a few miles away in a town called Amite. “We’re expanding,” Liuzza said. “A lot of expansions. I’m going to give credit to Walmart for that. But with that expansion is a lot of expenses.” We pulled into a field with a huge concrete platform in the middle of it. “I want to show you how we’re gonna gear up to do the proper job with Walmart,” Liuzza said, pointing out new cooling and packing and processing facilities they were building. “After working with them all these years, we thought, Well, yes, we’re taking a major chance, because we don’t need this facility if we don’t have their business as a vendor.”

I asked if this wasn’t a little worrying.

“With the economy being what it is, this is not the time to be going into the debt we’re going in. Okay? But we’re doing it. And it’s scary. But, so far, everything we’ve seen, they’ve been behind us.”

“They’ve even been behind us if we want to go to the other local DCs — in fact, they’ve asked us to,” Lizzy said. “They’ve been behind us throughout.” The Liuzzas said they had a close relationship with the company — “I deal with Walmart directly,” Lizzy said; “they want to know what weather we got coming up, what issues we have, they want to know everything” — but sent the paperwork and negotiated most of the deals through a third-party broker, in their case the Minnesota-based logistics giant C. H. Robinson. The prices Walmart gave them were good and consistent, and at every turn, the family felt, Walmart had treated them fairly and understood their needs.

Still, Liuzza had not forgotten why he had needed Walmart in the first place. He had been a big supplier for another supermarket chain — until one day he wasn’t. “We was really doing a lot of things to grow, and all of a sudden, we was still growing but they was done with us. It wasn’t over quality, it wasn’t over prices, it was just a change in direction they was going. The small little deal didn’t matter anymore,” he said. “It scared me — it like to broke me. But my son don’t have that memory. The Walmart deal’s everything for him. When it changed, I looked at my daddy and said, ‘What did we do? What did we do to deserve this?’ But Kevin don’t remember that. . . . He’s taking on a heap of debt to scale up for Walmart, a heap of debt.”

The other supermarket had decided that bigger suppliers made better financial sense. It seemed to me, I said, that Walmart could come to the same conclusion at any time. Liuzza insisted that it was different: he trusted Walmart; there was no reason they’d drop him if he offered them good product. But as I was leaving, he added, “At one time I went to a seminar at Walmart, and I’m listening, and at that time they said they didn’t really want to be over twenty-five percent of your business.”

“Is that still true?” I asked.

“I hope not,” he said, and laughed.

“How much of your business is Walmart?”

“I really don’t want to figure it out,” Liuzza said, and shook my hand and sent me on my way.

The 25 percent rule is in fact still a Walmart guideline, though, as I would learn when I reached Bentonville, the company knows that number isn’t realistic for smaller-size family farms. Nathan Winters, a farmer who has written for the website Fair Food Fight, summed up the problem to me this way: “Fifteen acres does not produce a lot of food. And Walmart needs a lot of food. So will the farmers try to grow in size? Of course. . . . What are they going to do? They’re going to scale up. Buy bigger machines, take out loans, get big. What happens when Walmart changes its mind?”

Walmart insists its locally sourced produce initiative is a permanent part of a “new global commitment to sustainable agriculture,” as the corporate press release has it, “that will help small and medium sized farmers expand their businesses, get more income for their products, and reduce the environmental impact of farming, while strengthening local economies and providing customers around the world with long-term access to affordable, high-quality, fresh food.” Agriculture is just one aspect of a massive sustainability push Walmart began rolling out several years ago, a very large, and very public, corporate commitment to preserving the earth, with the ultimate goal of 100 percent renewable energy and zero waste.

In 2005, then-CEO Lee Scott gave a speech broadcast live to all of Walmart’s 6,000 stores worldwide and to more than 60,000 of its suppliers. “What if we used our size and our resources to make this country and this earth an even better place for all of us?” he asked. But, he added, the motivation wasn’t purely altruistic. “Being a good steward of the environment and in our communities and being an efficient and profitable business are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are one and the same.” It’s a refrain Walmart has stuck to: This makes sense only if it is profitable. The economy, however, has not cooperated. And so green activists, many of whom have been encouraged by Walmart’s attempts to transform itself from a lumbering consumption machine into a lean, environmentally friendly animal, took note when, in March 2011, in the midst of the company’s worst domestic sales slump ever — profits had been flat or down for nine quarters (the latest numbers show a slight uptick) — U.S. division head Bill Simon warned the Wall Street Journal, “Sustainability and some of these other initiatives can be distracting if they don’t add to everyday low cost.”

Just a short drive south of the Liuzza property, I visited another berry grower, Eric Morrow, in Ponchatoula, which is known — at least in Ponchatoula — as the strawberry capital of the world and the home of an annual strawberry festival. (Morrow didn’t mention it, but later I discovered that he was the king of the 2002 strawberry festival.) An eighth-generation berry farmer, Morrow is a big, friendly man who lives on a road lined with massive live oaks that his great-great-grandfather planted in the 1850s. (The property officially became the Morrows’ in 1859 thanks to a land grant from President James Buchanan.) He started selling to Walmart — also through the broker C. H. Robinson — because of a program Walmart calls “Heritage Agriculture,” an initiative meant to reintroduce a diversity of crops to regions where they had once grown and subsequently languished. “In my grandfather’s time, they had more berries, if you can imagine this, in this parish and one other than they have in California today,” Morrow told me. “Over thirty thousand acres of berries.” And now? “Three hundred acres. Maybe. Maybe two hundred and fifty.”

[inline_ad ad=1]Morrow himself has fifteen acres of strawberries, some of which go to Walmart and the rest to smaller retailers and farmers’ markets. I asked what he thought Walmart was getting out of the deal, considering how much easier it would be — because of the amount of product they require to stock their thousands of stores — to buy in volume, and how much lower a price they could pay if they bought from someone with 15,000 acres instead of fifteen. Was he getting lowballed on the prices?

“I tell you what, Walmart gave me three dollars over the price of the market last year,” Morrow said. “Because they were getting product out of California, and the California prices were so cheap that we couldn’t make any money. California comes in, they got gobs of berries, and they’ll give ’em to you just to clean out the cooler. And what it does is it just kills our market here. The market was five and six dollars for twelve pints. You can’t even grow ’em and put ’em in the pot for five and six dollars. Robinson called Walmart, they said, ‘Man, our local guys are coming into the season, they just can’t survive on five or six dollars. It’s impossible. Can you give more?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, we’ll give them nine fifty. We want to build these guys up. We can’t cut their heads off.’ They’re looking into building this thing up. The way they’ve explained it to me is, everything’s gonna get tighter and tighter in California. The price of fuel is going way up. Up and up. So shipping is killing them. If you can get a product from here to a Walmart distribution center just a few miles up the road, then you ain’t got no trucking deal to pay for. You ain’t burning no diesel. But if you kill us you don’t have that option. So they want us to survive.”

From Morrow’s farm I went east past New Orleans into Mississippi, driving through torrential rains. In Jackson, I met Ben Burkett, a farmer from Petal, not far outside of Hattiesburg. Burkett, a fourth-generation grower who coordinates the Mississippi chapter of the Federation of Southern Cooperatives and is the president of the National Family Farm coalition, grew up with cotton in the Fifties and Sixties and now runs a 300-acre diversified family farm. It’s mostly vegetables, though he also raises livestock and grows some corn and soybeans. The land in Petal comes down from his great-grandfather, who, along with a few other African-American farmers, was granted a 164-acre homestead by Grover Cleveland, in 1889. We met at the downtown Marriott for a drink. Burkett brought along Dan Teague and Joe Barnes, outreach specialists with the Mississippi Association of Cooperatives.

“Walmart moving in on the small local markets — that can’t be good,” Barnes, the youngest of the three, and the most voluble, said immediately. “It’ll start off fine, Walmart’s gonna be great — at first. Then, once the other little local markets have been killed, once the other avenues have been taken out, once they sucked the life out of every other viable business on Main Street or on the side of the road — that’s gonna be a sad day, man.”

“Then they can control prices totally,” said Teague, a very large man with a deep, rolling voice.

“And they already don’t?” Barnes said.

“I’ve been in three meetings with Walmart in the last three or four months,” Burkett said, speaking considerably more slowly than Teague and Barnes. “We had all the senior vice presidents, I think we had everybody except one of them Waltons. I think it’s a wait-and-see thing. If it works like they say, it’s gonna be a good thing for small and family farmers.” Burkett thought that the money Walmart saved on trucking fruits and vegetables across the country had a good chance of making the initiative profitable.

I asked whether popular interest in the local-food movement had made any difference that they could see.

“It’s not such a big thing here in Mississippi, but I’ve seen the emergence of farmers’ markets,” Burkett said. “Every town wants one or got one. But the problem now, there ain’t enough farmers to go round.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“What happened?” Barnes said. “Most people, especially minority farmers, the ones who went north — like my parents — they want no part of farming. They did it. Mama pulled cotton, Daddy pulled cotton, planted corn — and they left. For those good-paying jobs. After that? After cotton? That’s a pie job to them, twelve hours in a factory. That’s pie! Plus to get paid a real wage, benefits.”

As small-scale farmers switched to factory work, a major shift occurred in agriculture. “My father used to farm about forty acres of cotton, soybeans, some hogs, some cows,” Teague said. “So he was very diverse, but he wasn’t a big operation.”

“From 1969 to now,” Burkett said, “it’s been the same. That’s when it started, with get-big-or-get-out. You got your petroleum-based farming, chemical-based farming. The Nixon Administration’s Farm Bill: Make food cheap for the American people. Keep food cheap at the expense of the family farm.”

“And that drove them out of business,” Teague said.

“It took us from 1970 till now to get in this mess,” Burkett said. “That’s forty years.”

“Forty years,” said Teague.

“Forty years to get where we’re at,” Burkett said. “So it’s gonna take forty years to get out.”

Today, around 33,000 farms — 0.15 percent of the 2.2 million in the United States — account for about half of all agricultural revenue. The various food movements of the late twentieth century and early twenty-first — local, organic, slow, and so on — haven’t coalesced into a single revolution, but what they have in common is the desire to replace global corporate food production, dependent on fuel and chemicals and giant operations, with smaller, more diversified local food systems.

I spoke with Michael Pollan, the author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma and one of the culture’s leading chroniclers of how we feed ourselves, to ask what he thought of Walmart’s local-produce plan. “I think it’s the most important of the various initiatives they’ve announced,” he told me. “But if the food doesn’t sell as well, who knows if they’ll stick with it.” The farmers, he feared, had no bargaining power. “I’ve had suppliers tell me, ‘Well, Walmart came back and said, Sorry, this year we’re cutting back ten percent, end of story.’ ”

Anthony Flaccavento, an organic farmer in Virginia, was also pessimistic. “What they do is bring suppliers in and then bring them to their knees,” he told me. Flaccavento, who also runs a consulting business dedicated to supporting ecologically sound food systems and is currently running for Congress, worried that Walmart would start out strong, offering fair prices and good deals, and then, once the growers became dependent on the company, squeeze them. “They’ve done some things that are commendable,” he said. “But any risk is passed back to the producer.”

And not everyone agrees that if Walmart simply treats farmers well it will be an unequivocal victory. As Pollan puts it, “The local-food movement wants to decentralize the global economy, if not secede from it altogether.”

I asked Alice Waters, the owner of the restaurant Chez Panisse and a longtime promoter of local and organic food, what she thought about the support of people like Michelle Obama for Walmart’s affordable healthy food initiatives.

“I’m behind her,” Waters said. “And I believe, and I only believe because she has told me I should, in the right thinking of Walmart.”

But right thinking aside — and though Waters was generally positive about Walmart’s specific initiatives — Walmart’s doing more is not exactly the road to paradise she had imagined. “The way that organic farmers care for their food production is very different from farmers in the industrial model,” she said. “And things are pretty fragile in the organic world. They’re not grown to be shipped. If it can be local enough to go in and out in the same day —”

“Walmart is defining local as grown and sold in the same state,” I said.

“I think it would be fabulous if Walmart just gutted all its stores and turned them into giant farmers’ markets,” Waters said, laughing. “I mean, really! Just gutted.”

Through Mississippi and heading back across northeastern Louisiana, I stopped at Mom and Pop’s Fresh Produce, off the side of the road on the edge of Transylvania, in East Carroll Parish, not far from the Arkansas border: a couple of tables under a tin roof, run by an elderly pair of farmers, Harold Shelton and Alta Lovell. I bought some delicious pickled squash ($5.00), which they’d grown and jarred on the quarter acre they lease from the owners of a 6,000-acre farm. I asked them if making a living was tougher than it used to be for a small farmer. “All kind of farming’s tougher than it used to be,” Shelton said. “Six thousand or sixty or six, it’s no kind of living from how it was.”

In Prairie Grove, Arkansas, about forty miles south of Bentonville, I heard the opposite point of view from Dave Sargent. I’d been thinking of Sargent, a seventy-one-year-old grower, as Walmart’s Favorite Farmer: they’ve featured him in commercials, invited him to speak on panels, and thrown his picture on leaflets and posters, just the perfect expression of authentic American hard work rewarded. For most of his life Sargent was a dairy farmer, with a six-year stint in the Army and a sideline career as an author of children’s books; he didn’t start growing produce until the age of sixty-two, when he planted a garden on a third of an acre behind his house.

“And my gosh,” Sargent said, “I had more stuff than I could possibly use or give away.” He began selling to local markets, and then to Walmart: first one supercenter, then two more, and pretty soon to all the Walmarts in the area, and then to the distribution center. In less than a decade, he had turned a garden into a million-dollar business. “You can be as big as you want, you can be as small as you want,” he said.

It sounded pretty simple — do the work and Walmart will take care of you. “Walmart is the best company in the world,” he told me.

An hour away, I met Randy Hardin, a fourth-generation farmer who runs a 1,600-acre farm in Grady, Arkansas. I found him at his retail market in Scott, not far from Little Rock, where he sells vegetables and fruits, jellies and jams and that sort of thing, and runs a sandwich counter.

“It’s a setup! It’s smoke and mirrors,” Hardin said. “They’re gonna draw us in and then kill us off, one by one.” Hardin, a beefy, bearded, no-nonsense type — though none of these farmers seemed like they were much in the nonsense-brooking business — had sold watermelons and pumpkins to Walmart, but swore he never would again. Walmart rejected perfect produce, he said, because it generally ordered more than it needed. If a farmer showed up at the DC after it had filled its quota, Walmart pretended that what he’d brought wasn’t up to their standards.

I’d already had a brief conversation with Hardin’s son Josh, and he had expressed some doubts of his own, if more temperately. “They get to say, ‘Look what we’re doing for your community.’ But we’re not some faceless global corporation — we’re right here. And if I’m going to let them use me like that, I need a commitment in return.”

Now Hardin’s older son, Jody, sat down with us.

“I’ve been working with Walmart, trying to figure out how to work with local farmers,” Jody said quietly. He added that he hadn’t told anyone outside the family about it, worried that meeting with Walmart might lose him credibility in the work he was doing to organize Arkansas farmers’ markets and growers’ cooperatives. “I mean, look at him!” he said, pointing at his father. “You mention Walmart and he says, ‘Aaaaah! Ooahh ooahh ooahh!’ So I know better than to talk about it to him, but I’ve been meeting with them every winter for the last three years to do a national plan for Walmart to work with small farmers.”

“And they’ve been using him just like, just like, a piece of toilet paper,” Randy said.

“Isn’t it a good thing that they want his opinion?” I asked.

“That’s exactly why I go to the meetings,” Jody said. “Somebody needs to speak for the farmers.” What Jody felt was most important was infrastructure — shared collection, packing, and processing facilities for the wholesale market — and he hoped Walmart would be willing to invest in communal planting and harvesting equipment for farmers.

“Which is something they’re talking about doing,” I said.

“Yeah, they’re talking about it,” Jody said. “And my clear statement to them was, once you isolate a farmer, that’s trouble. We could go out together as a cooperative of farmers. But they tend to take those farmers and isolate them, and drive their prices down, with separate agreements. And that’s exactly what I’m saying I won’t go into business with.”

“Well, that’s their whole deal!” Randy said. “And they’re picking your brains to compete with us! In other words, they’re riding to the bank on our backs. They’re plotting. Their whole deal is, one farmer against another. One grower against another.” Jody laughed but didn’t argue. “More growers, more producers, more everything than they need, so they always have the advantage,” Randy said. “You’re at their mercy. That’s the name of the game. . . . They want to control the whole deal, from the A to the Z.”

“They’re integrating,” said Jody.

“Integrating!” Randy said. “You can call it whatever you want. I call it absolute control. These little markets right here are a thorn in the side of Walmart. I went to Sam’s Club [which Walmart owns]. They were sampling seedless watermelons. They were sampling them, and I got a taste, and it was one of the worst watermelons I’ve ever tasted. But every person in that store was buying them.”

“Here’s what Walmart’s paying for them, Dad,” Jody said. “They’re paying twelve to seventeen cents a pound. The national average last year was seven to eight cents a pound. They’re gonna sling that in your face. They’re gonna say, ‘This is what we paid on average,’ so they can shut people up like you.”

“But you know what the market on seedless watermelons, if you can get ’em, has been for the last two months?” Randy asked. “Twenty-two to twenty-six cents a pound.”

“Let’s see what Walmart’s paying right now.”

“I bet they’re paying fourteen cents a pound,” said Randy, and started punching numbers into his cell phone. “Lemme ask you a question,” he barked into the phone. “What is Walmart paying for seedless watermelons right now? What’s the market? What’s —”

“My dad’s still bitter from bad experiences,” Jody told me in a low voice. “But I think they’ve come a long way. I think if he met with them he’d be impressed.”

Randy was off the phone. “Market’s twenty-four to twenty-six if you can find ’em,” he said. “Walmart’s paying fifteen.”

“That’s what they average,” Jody said. “And Walmart’ll tell you that when watermelons drop to seven to eight cents they’ll still pay fifteen.”

“So they’re not affected by the market?” I asked.

Randy snorted. “They control the market! They are the market. And that’s what they intend to do with these smaller stores. That’s what they’re missing right now. And when they eliminate this thorn in their side, then they control the whole ball game. I never called them dumb, did I?”

I pulled into Bentonville on a Sunday. The town is, on its face, standard American sprawl: pleasant houses with lawns, strip malls along a main thoroughfare (Walton Boulevard), and chain hotels all down the way. On the street where the Home Office is located, I saw a large sign that said so far this year, we have saved families, and below it an LCD screen read $199,575,567,130. (This figure is from research, I was told by Walmart representatives, that found Walmart saves every U.S. family $3,100 a year, whether they shop there or not.)

The Home Office itself is an architectural achievement in nondescriptness: just a few stories high, and built so you can’t really tell how much ground it covers without an aerial view. It communicates no real trace of any kind of power or wealth, no imposing or impressive Late Triumphalist Facelessness or Postmodern Total Dominion. This is what I like about the behemoth and the auto-body shop, to return to the matter of Keith. His business doesn’t look like it got dropped on the wrong block by mistake.

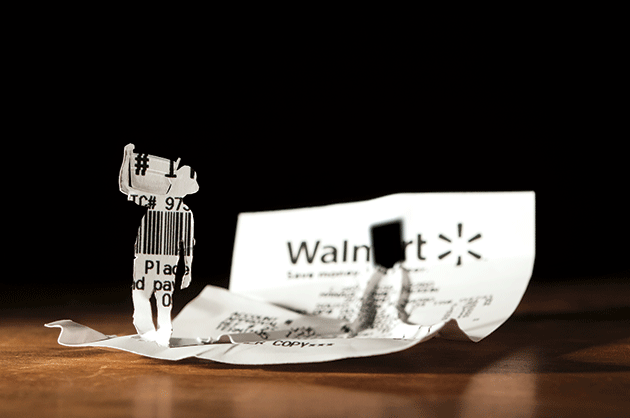

Their proximity fits perfectly within the image the company wants to project, and within the model of what it actually does. The Walmart press-release writers would argue that the company has grown so large by staying in close touch with its own local roots, in touch with the needs and demands of the small communities it serves. What’s clear is that never before has a company grown so big by the manipulation of the small. It is the third-largest employer in the world, after the U.S. Department of Defense and the People’s Liberation Army of China, and it has grown to this position by relying on the poor and middle-class people who work and shop at Walmart stores.

Inside the Home Office is a labyrinthine set of hallways and cubicles, suitably shabby. I was led to a small cubicle where Ron McCormick, senior director of local and sustainable sourcing, was waiting. McCormick told me Walmart was going to make money on the deal with local farms. “For us, produce in particular is one of those items where freight is a disproportionate cost of the goods,” he said. “But if we can buy the product close to the distribution centers, this gives us a substantial freight savings, which gives us a strong competitive advantage that not everyone can duplicate. So there’s a strong business motivation just from the logistics.”

I asked whether losing out on economies of scale didn’t offset the shipping savings.

“If I’m buying a hard good that I can store forever, being able to buy a full truckload in California as opposed to a quarter of a truckload in Illinois, there’s nothing there,” McCormick conceded. “But if it’s a highly perishable item — in three days it’s going to be trash — the economy of scale is more than outweighed by the amount of product we throw away. We throw away a shocking amount of food.” And, he added, “If we can save three dollars a case in freight, we can do a lot with that three dollars. . . . We can pay to the cost of production. Because no matter how efficient we are, it will always cost more to grow that product in some parts of the country. . . . So we can take a portion of that saved freight and pay that farmer more.”

I asked about any reputation problems among small farmers.

“We used to have a lot of small regional local producers we did business with,” McCormick said. “What we found was that on those occasions that our local buyers would go visit those farmers, or just at a convention or some industry meeting, they’d hear these horror stories about how bad it was to do business with Walmart. . . . We’re going, ‘Okay, we think we’re pretty fine people, how did we manage to become the devil of the industry?’ What we found out was that if we allowed it to be an invisible process, our best suppliers did a great job — even the mediocre suppliers still did a decent job of it — but then there were still a lot of people who were literally telling the farmers, ‘Look, I can only pay you four dollars. You know how Walmart is, they pound us down, they beat us up, all we can pay is four.’ We may have been paying nine dollars to that supplier, but they were telling the farmer, ‘Hey, I have to make a little profit here, Walmart’s paying seven dollars, I know the market says eight fifty, but that’s it.’ ”

They were lying and gouging, I said.

“They were gouging. So we understood we need to make it a three-way conversation,” McCormick said. They needed more direct contact with the farmers themselves. But small farmers weren’t necessarily equipped for all the paperwork, the insurance, and so forth, without those middlemen. The best solution, McCormick thought, would probably include more farmer-run cooperatives, and Walmart wanted to encourage that. This was good news for the farmers, I thought: he was saying Walmart wanted the same thing as the growers had told me they did, a way for farmers to come together to share costs and achieve some negotiating power without losing out to more middlemen.

Are corporations changing? I asked. Was this part of an evolution of the idea of what a corporation should be?

McCormick wasn’t ready to confess to all that. “I think our senior executives, Mr. Scott, and now Mike Duke,” he said, “have been very vocal and up-front telling people that with all the sustainability work we do, there’s an element of self-interest there. Lee Scott used to call it ‘earning our license to grow.’ Because this is a growth company. So we have to be the kind of company that people would want to grow . . . We want to be the kind of company that provides transparency to the people about what we’re buying, how we’re buying — to have the sort of corporate citizenship that would make people say, ‘I want to shop at Walmart.’ And feel good about what they’re doing.”

McCormick’s words were echoed by Beth Keck, Walmart’s senior director for sustainability, when I asked her whether there were any political drawbacks to the sustainability initiatives — whether consumers might be turned off, seeing it as some liberal tree-hugging waste of time and effort.

“I see us as a very mainstream business, and we’re a very down-to-earth business as well,” Keck said. “Because, you know, our everyday consumer is just an average person, and many of them live paycheck to paycheck. And our promise to them is very simple: that they should never have to choose between a sustainable product and one they can afford. We’re very conscious of the mission to bring these two together. And I think that supersedes politics. It’s really all about bringing our consumer the best value.”

I was puzzled for a moment about the consistency of these lines of argument from McCormick and Keck — We’re not out to save the world; we’re doing this for our customers and for our bottom line — until what should have been obvious finally occurred to me: that in our conversations they were actually addressing their shareholders. Sustainability would improve efficiency, and thereby increase profit. Sustainability would improve Walmart’s image, and thereby increase profit. Sustainability would allow growth, and growth was profit.

Jim Prevor, who runs Perishable Pundit, a website dedicated to covering the produce industry, told me, “Things have not been good at Walmart. So there’s tremendous pressure to produce more sales and more profits.” But part of the problem is that food is rising as a percentage of the company’s sales, and food is still a low-margin item — big profits come on lawn mowers, not peaches. “One day, Walmart’s going to need earnings, and the word will come down to their buyers: Find money. And these people” — the growers — “will be very, very vulnerable.”

Whether that vulnerability should be Walmart’s responsibility — whether Citizen Walmart should be expected to do something more than simply make money any legal way it can — is an ethical question no one at the company wanted to address.

This past spring, Walmart announced it had already increased its local-food sourcing from 4.5 to 10 percent of total sales, beating the 9 percent goal four years ahead of schedule. The road to sustainability, it seemed, was even smoother than the company thought it would be. But that 10 percent, and the speed with which Walmart got there, represents a lot of farmers like the Liuzzas making risky investments in order to scale up quickly.

Food grown by sustainable practices shouldn’t be something only the wealthy can afford, and perhaps Walmart has the will to do something about that. But it’s a problem that so many farmers are being kept alive by the good graces of one of the biggest companies in the world: they wouldn’t be the first to perish hoping their despots would remain forever enlightened. The retailer says it saves Americans money whether they shop there or not, but this also means that its choices affect Americans in all sorts of ways it can’t control. In this instance, the more Walmart buys local, the more it changes what local means.

In Ponchatoula, I stopped by the Liuzzas’ retail farm stand, Berry Town Produce, and picked out some jellies made from fruits I’d never heard of. When I asked two elderly ladies if they could tell me what mayhaw jelly was, this produced some argument: what exactly the season was, whether the red ones were better than the yellow ones, how much like a grape it was, what the differences between mayhaw and muscadine were. (I later read that a mayhaw is an edible early ripening hawthorn that grows, in Louisiana, from mid-April to early May.) But one thing was easily agreed upon: there was less of it than there used to be.

“When we was children they fed it to us so much I thought I’d choke on it,” one of the ladies said.

“They have mayhaw jelly in Walmart?” I asked.

“Oh, heck no,” said the second lady.

“They have everything,” I said.

“No mayhaw jelly,” said the first.

“They don’t got it in California, they don’t got it in Ponchatoula,” the second lady said.

“Maybe that’ll change,” I said.

“Maybe,” the first lady said. “In the meantime, I advise you to buy two jars.”