Drawings by Olivier Kugler

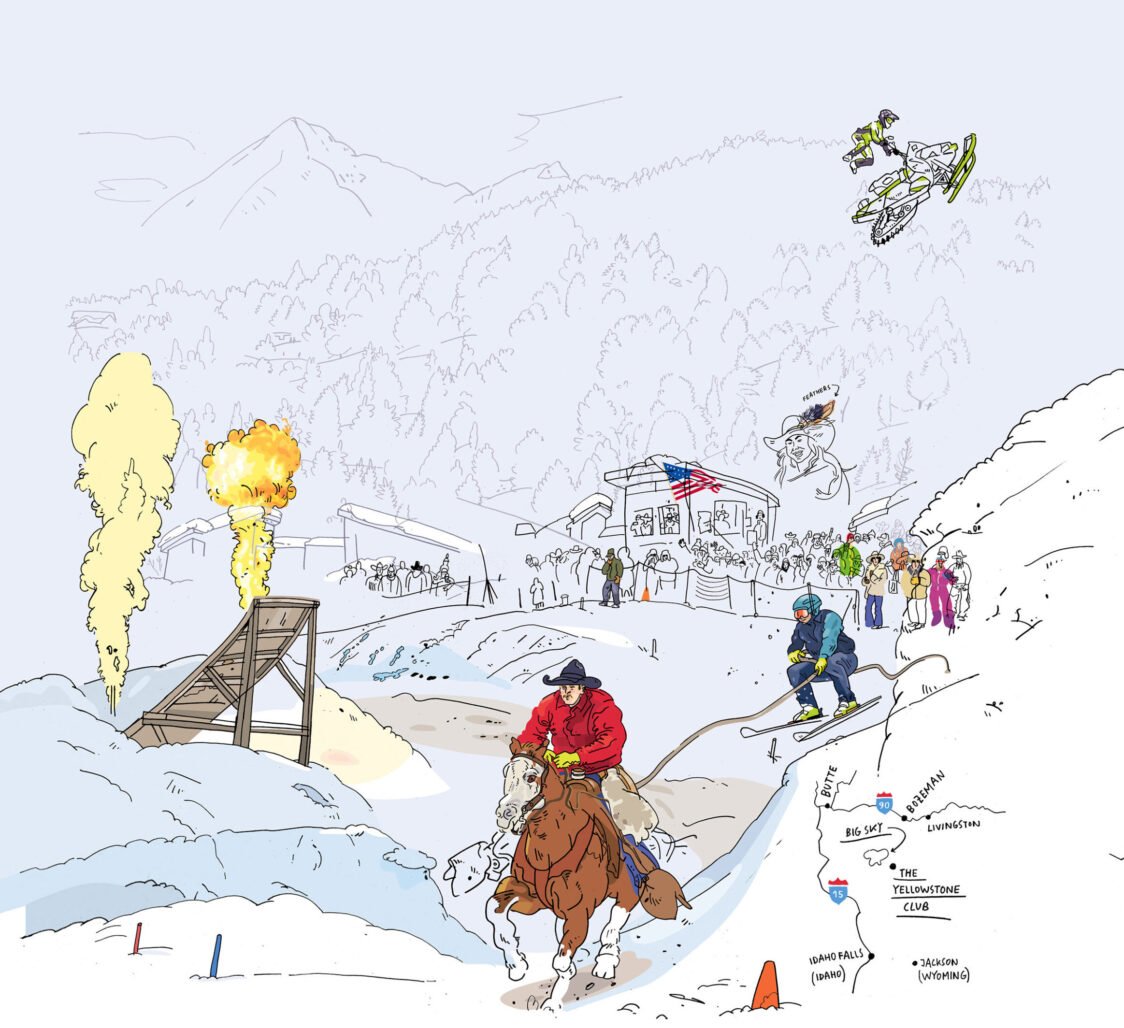

Last February, on a warm day with few clouds, thousands of people gathered on an icy lot in Big Sky, Montana, to watch a skijoring competition—a race contested by awkward hybrids of human and horse. A saddled rider pulls a skier or snowboarder who is attached to a thirty-three-foot rope tied to the saddle horn, through a gauntlet of snowy jumps, walls, and poles. Riders drifted past the crowd, grinning and clutching beer cans, and a team of freestyle snowmobilers launched backflips off a jump, interspersed with jets of flame. Pop-country blared while two announcers tried to make the crowd laugh.

“I remember things better when I’ve been induced by alcohol,” one quipped.

“That’s what she said.”

I found myself digging a trench in the snow to avoid sliding down the icy hill where a ranch hand named Maddie was standing. She and her boyfriend worked at a local ranch but lived in Bozeman, about forty-five miles northeast, in an apartment owned by their boss. Maddie didn’t care for Big Sky. The objects of her disdain were all around us: the ski-town elite, mixed into the crowd but easy to spot in their high-end Western wear, the women in wide-brim hats with feathers in the band and the men in tight Wranglers and designer boots. Off in the distance jutted a prominent, long-dormant volcano: Lone Mountain, home to Big Sky Resort, one of North America’s largest ski destinations.

“I hate it here,” she told me.

It’s a familiar sentiment these days in Montana, one of the country’s fastest-growing states. You often hear it in shorthand—in Bozeman’s nickname “Boz Angeles,” for the influx of Californians, or in the popular anecdotes, like the one about a duck hunter ticketed for trespassing on land where he had hunted since childhood, recently purchased by millionaires. “You’ll overhear them talking about how they’re coming on vacation from San Francisco or L.A.,” a Big Sky ski-lift operator told me of the newcomers. “And then they come out here, like, ‘This is my favorite place to come—I love wearing my cowboy hat, my cowboy boots.’ ”

These circumstances didn’t surprise me. I live in Gunnison, a town of nearly seven thousand people at 7,700 feet in western Colorado. Just to the north is Crested Butte, one of the state’s iconic ski towns, where I spent several years making extra money by bartending, mixing drinks for vacation-home owners and cracking open endless cans of PBR for spring-break revelers. We have our own examples of wild excess in the high country; during peak ski or foliage season, private jets, some painted with the Lone Star flag, descend on the county airport. We also rely on an enormous winter workforce of young, often white seasonal workers, along with rapidly growing populations of Central and South American migrants who tend to do construction, cleaning, and restaurant work.

At the bar, I worked with a few people who had passed through Big Sky, and I’d heard about it as the epitome of these forces: great skiing, awful housing, billionaire indulgence. I had never been there; the $260 peak-season lift ticket was an obstacle for someone on a journalist’s salary. Even so, I began to poke around; I wanted to see the place that the New York Times dubbed “the future of skiing.”

And Big Sky stands apart for other reasons. The obvious distinction is the Yellowstone Club, a private resort hidden in the mountains above the community that Justin Farrell, a professor of sociology at Yale and the author of Billionaire Wilderness, has described as “the pinnacle, or inevitable telos, of the trajectory of extreme wealth concentration in the United States.” The club is one of the most exclusive institutions on the planet. Guards watch its gates, and Google Street View doesn’t show its streets. It has its own ski mountain, a fire department, and a restaurant overseen by a celebrity chef; people who have worked inside describe thirteen-thousand-square-foot homes and sharkskin bar tops. The club’s members reportedly include Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, Eric Schmidt, and Warren Buffett. As of 2019, new members put down a $400,000 deposit and paid about $44,000 in annual fees, according to Mansion Global. Those with the means can buy property on the club’s land, and sources note that sale prices can be well north of $20 million. Current and former employees insisted on anonymity, fearing retaliation from an institution that employs a private security force.

In recent years, CrossHarbor Capital Partners, the private-equity firm that owns the Yellowstone Club, has emerged from behind the club’s walls and directed its financial might at the broader Big Sky area. Through Lone Mountain Land Company, the developer it owns and uses to conduct local business, CrossHarbor owns at least thirty properties, worth about $135 million, in what people regard as Big Sky’s downtown area, according to a Harper’s Magazine analysis of publicly available Montana property data; it also owns hundreds of acres, including all the undeveloped residential and commercial land in the same sector. It is also one of the area’s prominent landlords, with hundreds of housing units for community members. Big Sky is unincorporated, with no mayor, no city council, few of the representative bodies that a standard local government would provide. Instead, over decades, a patchwork of hundreds of homeowners’ associations (HOAs), special districts, volunteer boards, and nonprofits—notably the Yellowstone Club Community Foundation—has come together to manage the community. That didn’t matter so much years ago, when Big Sky was a sleepy hamlet. But today, the median home price is more than $2.5 million. And CrossHarbor, via its local affiliates like Lone Mountain, stepped into this regulatory void, gaining increased power by virtue of its financial portfolio. Farrell put it bluntly. “Big Sky is a strange town,” he told me, “in the sense that it’s not really a town.”

Even at the skijoring event, amid the loose, loud carousing, where the high-mountain air sent alcohol straight to the head and the grassy smell of horses and weed smoke drifted over the crowd, the powers that increasingly control Big Sky were close at hand. Banners displayed the event’s sponsors, including an insignia representing Lone Peak, mirrored, off in the distance, by the real thing. It’s the logo of Lone Mountain Land Company, which was, unsurprisingly, one of the event’s top sponsors, and the owner of the land on which the crowd cheered as the horses pulled skiers across the snow.

The forces that are remaking the Mountain West—the consolidation of land and wealth in the hands of a few, the circulation of global capital, the substitution of corporate power for civic authority—are uniquely visible in Big Sky, where private interests affect the very structure of the community. Tucker Roundy, who moved to Big Sky eleven years ago and began stocking shelves at the Hungry Moose Market and Deli, used a common phrase when describing the community’s dynamics to me. “With Lone Mountain buying the Town Center area, it’ll be interesting to see what the next five to ten years hold for Big Sky,” he said, “and how much of a company town it becomes.”

Big Sky’s leaders dismiss that label. “You hear that criticism a lot, when you have those conversations on barstools,” David O’Connor, executive director of Big Sky Community Housing Trust, told me. Daniel Bierschwale, executive director of the Big Sky Resort Area District (BSRAD), insisted that there are multiple representative bodies. Within the tax district, which covers the downtown of Big Sky, the surrounding resorts, and the Yellowstone Club, BSRAD collects a sales tax on “luxury” items, raking in nearly $19 million in 2022. A quarter of this money funds local infrastructure. The rest goes to things like the fire department and conservation projects. A five-person board, elected by Big Sky voters every four years, distributes the funds. “It is inaccurate to say there is no government,” Bierschwale said.

A Lone Mountain Land Company representative, meanwhile, emphasized in an email that the company is made up of locals committed to making Big Sky “a thriving year-around livable community, not just a resort destination”—and that Big Sky is “governed and overseen by its residents.”

But in Big Sky, there’s a pervasive sense that BSRAD fails to give residents equal standing, and that the board ultimately answers to the Yellowstone Club, Lone Mountain, and CrossHarbor. Three of the five board seats are currently held by people associated with the Yellowstone Club or Lone Mountain Land Company. Other members of CrossHarbor’s network appear on Big Sky’s transportation and water and sewer boards. Roundy, for his part, became interested in BSRAD after it applied the sales tax to cases of beer and bottles of wine, which he thought would disproportionately target locals. So, in 2020, he decided to run for a board seat, hoping to address infrastructure needs and affordable housing. Since many seasonal workers do not vote, Roundy wasn’t exactly surprised when he was trounced.

In my county in Colorado, a financier named Mark Walter has purchased seemingly half of Crested Butte’s main street. In Aspen, a Russian billionaire sued a local newspaper for describing him as an oligarch. At lower altitudes, there are plenty of strange new examples of powerful private financial interests operating in unusual jurisdictions: legislation that allowed Walt Disney World to be an essentially self-governing territory in Florida; Amazon’s soliciting enormous concessions from cities across the country in its search for a second headquarters; Elon Musk’s purchasing thousands of acres of land outside Austin, Texas, where he intends to incorporate a new town. Brian Highsmith, a fellow at Harvard Law School who studies corporate power and local government, agreed with Roundy, describing these examples to me as contemporary company towns—now often achieved via extreme concentrations of property ownership that allow for private interests to gradually take hold of local democratic processes.

In recreational meccas like Big Sky, the kind of extravagant wealth visible throughout American life reaches a new register. Privacy, as Farrell notes in Billionaire Wilderness, is determined in these places not only physically—as with the Yellowstone Club’s walls—but in more diffuse ways, via regulatory capture, fragile seasonal jobs, and limited housing. “Unsurprisingly, this sows seeds of distrust and resentment within communities, who fear that they are losing control in this new gilded age,” Farrell writes, “where huge swaths of cherished land are being purchased and closed off, for the occasional enjoyment of a select few.”

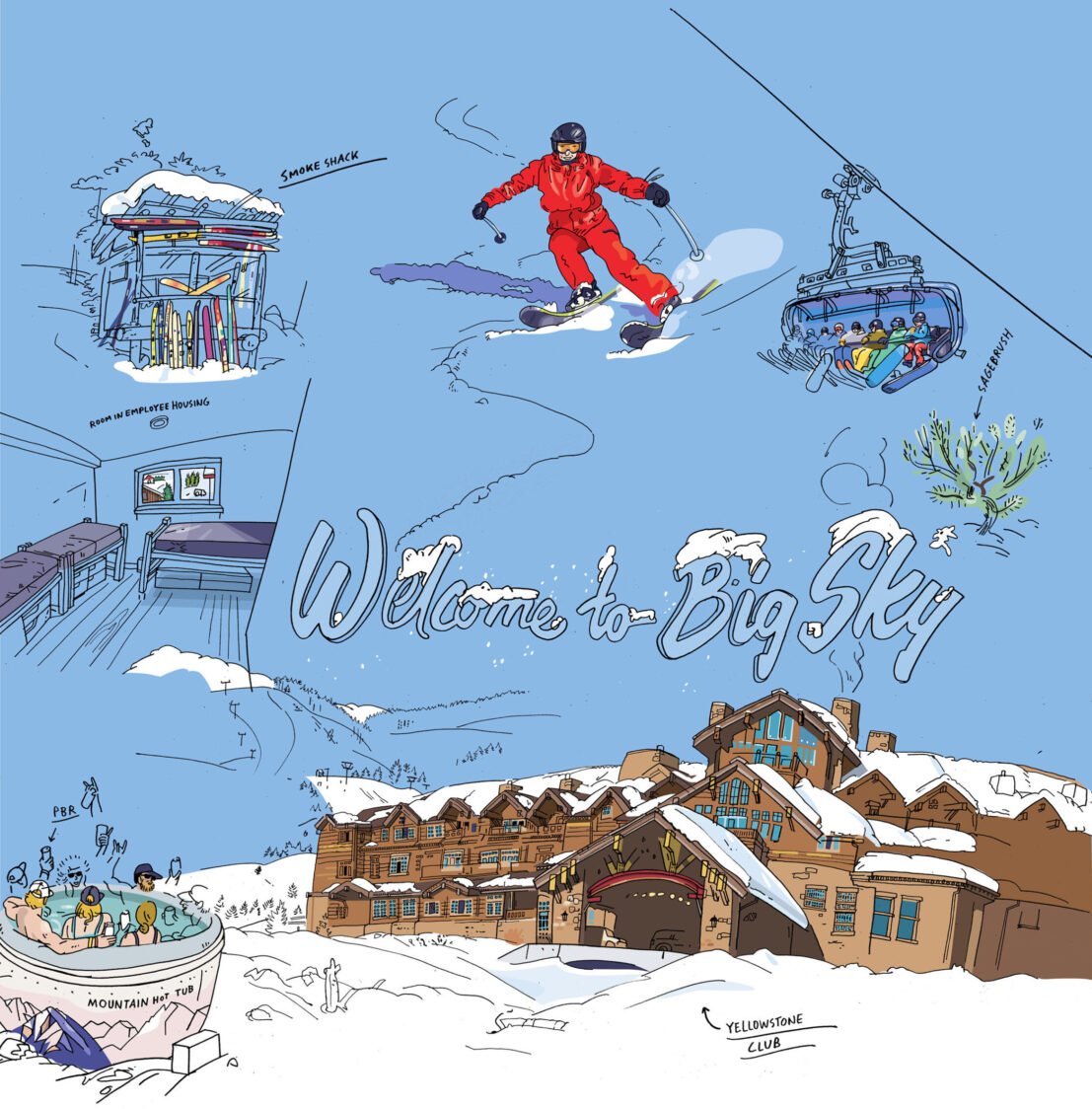

The biggest skiing in america: the slogan was plastered all over Big Sky Resort, but I hardly needed the reminder after my visit last winter. That morning, I met Elise Otto in the parking lot before the chairlifts started running. Otto is pursuing a Ph.D. in geography at the University of Arizona, but she had spent eight years as a private ski instructor at the resort. She once told me that “skiing makes you live with multiple ontologies.” The day before, while walking around one of Lone Mountain’s new luxury hotels, she suggested that if skiing denotes anything besides simple pleasure-seeking, it is regular exposure to extreme physical risk.

In the base-area warming hut, we were joined by Noelle Hart, an instructor employed by the resort, who greeted us jovially in a bright-red snowsuit. Hart was technically showing up to her workplace, but she seemed as excited to get on the slopes as any vacationer. (When I asked her about her employment history over her twenty-two years in Big Sky, she summed it up simply: “Just kept skiing.”) Both Otto and Hart possess an easy, almost haughty physical confidence on the slopes, while I fell behind immediately, wearing ski boots I had bought in college. (Months later, when I told Otto that I had finally donated them to a used-gear store, she said that they’d make great flowerpots.) We finally paused in a glade at a small lean-to, made of logs and old skis, half covered in snow. These structures hide throughout the resort as relics of its less-polished past, and are known as “smoke shacks.”

Otto and Hart were talking about the travails of ski instructing. Otto used to ski with clients who paid $1,200 per day for private lessons, and she would encounter people used to being in charge—a power dynamic aided by the basic challenges of skiing at Big Sky. “Most people don’t start off respectful,” she said later, “but almost without fail they end up respectful, because you get scared out there.” They also talked about the resort’s expansion to a whopping 5,850 skiable acres, thanks to a deal made just over ten years ago between the current owners of the public resort—Boyne USA—and CrossHarbor. Big Sky is famous for its size, its extreme terrain, and its long, steep cirques high above the tree line. Mere minutes into the day, my legs began to ache.

Each winter, around one hundred ski patrollers strive to keep the hordes of visitors to Big Sky’s slopes safe. I met one during my visit named Jack Braley, who got the job after bouncing between ski resorts around the country. Braley told me that he admitted to himself that he would “never be rich,” but that patrolling provides him a combination of fulfilling work and more financial stability than other ski gigs. “There’s more of a career in it,” he said.

But even in these more stable corners of Big Sky’s workforce, cracks are starting to show. Staffing issues have plagued the resort in recent years, in part because prospective recruits couldn’t find affordable housing. Patrollers are hopeful that their new union—certified by an overwhelming vote in 2021—will help with issues like low pay, inadequate benefits, and crushing workloads. Employees report that the Big Sky Resort has raised wages across the board, perhaps owing to pressure from the union vote, while the patrollers recently received a substantial hourly rate increase.

Hart eventually left for a lesson, and Otto and I made our way to the tram, from which we could see Big Sky’s iconic run, the Big Couloir, a long, sheer, forty-degree chute between jutting rocks. “Most of the run is a no-fall zone,” Otto told me as she pointed it out—a skier who falters could tumble a potentially fatal distance. The top of Lone Peak offers an unobstructed panorama of the surrounding mountains. After taking in the view, we made an unspoken agreement that we would not take on “The Big,” as it is known, and Otto led me down to another run, for some reason named Marx. On another chairlift that afternoon, we sat next to a talkative young man who told us about the two-year warranty on his $375 ski gloves.

Otto and I worked our way across the flanks of Lone Peak to the resort’s southern edge, where Big Sky Resort abuts the perimeter of the Yellowstone Club. In the distance, I could make out a large central lodge and rows of multistory houses with peaked gables and exposed wooden beams, their roofs neatly covered in snow, like buildings in a snow globe. A chairlift doubled back at the base of the private ski mountain, where I could see a few figures gliding gently down the white face. An orange no trespassing sign was bolted to a nearby tree. On it, someone had placed a sticker: fuck the yellowstone club.

Since its beginning, Big Sky has been run by developers and HOAs. Until the Seventies, the area where Town Center and the resort sit today was an expanse of undeveloped and national-forest land. Enter Chet Huntley, an NBC evening news anchor. Huntley had grown up in Montana and often returned on vacation. He dreamed of building a mountain recreation haven, one free from the heavy hand of the government, which he once described to Life magazine as “an insufferable jungle of self-serving bureaucrats.”

Huntley became the square-jawed face of an investment group made up of corporate giants that wanted to acquire the public land at the West Fork of the Gallatin River. The group concocted a series of land swaps with the U.S. Forest Service, eventually acquiring thousands of acres for a new town and ski resort. Huntley died in 1974 of lung cancer, barely three months after the resort’s opening, but his spirit lingered, and the community that grew up with the resort was never incorporated. Services like the post office and the installation of street signs were administered by the Big Sky Owners Association, which, in 1972, “assumed the mantle of municipality,” according to its website.

The resort was eventually sold to Boyne USA, and the mountain thrived in the Eighties and Nineties for one very simple reason: phenomenal skiing. Big Sky developed a shaggy-dog reputation among Western resorts, grittier and harder to get to than Aspen or Vail, with extreme terrain that matched or surpassed its posh Colorado cousins. A 1997 High Country News article described it as “famous for not being too famous.” Old-timers recall a place with cheap housing and roadhouse bars, where the ski-season workers would carouse all night. Other parts of the early era were less charming: with no centralized water system, septic tanks reportedly proliferated and tended to leak, creating underground sewage lagoons that caused massive green-algae blooms in the river.

Like the resort, the Yellowstone Club’s origins involve Forest Service land swaps, this time with Tim Blixseth, a brash timber baron from an impoverished Oregon logging town. In the Nineties, Blixseth wound up with a large chunk of forest between Yellowstone National Park and Big Sky Resort, where he set out to build an exclusive refuge for the superrich, which became known as “private powder,” a phrase the club trademarked in 2005. Bill Gates bought in, as did former vice president Dan Quayle and three-time Tour de France champion Greg LeMond.

Hart, the ski instructor, was there from the beginning. Late one Tuesday afternoon, before she picked up her kids, I met her at the Korner Klub, a longtime watering hole at a highway intersection west of Bozeman. She came down to meet me from Belgrade, one of a number of small towns once affordable for people like her—she holds three jobs year-round—but where housing prices have now tripled. Hart is funny, blunt, and a willing storyteller about her early days at the club, when she was paid to ski and socialize with some of the most famous people on the planet. “We were paid to go to Christmas parties and be the members’ friends,” she recalled. Gates was “just ‘Bill’ at the club,” she recalled, “in this white T-shirt.”

Blixseth’s net worth reached $1.3 billion by 2007, according to Forbes, but the Yellowstone Club filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy during the Great Recession. Years of litigation followed, and Blixseth went to jail twice for contempt of court. I asked Hart if he ever comes back to Big Sky. “No, no,” she said immediately. “He would get shot.” Hart had some choice descriptors for him—“flamboyantly fake,” “very much a chode”—but she also called him a visionary. Blixseth rejected the traditional ski-town model that attracted middle-class families for single vacations, having realized that the real money was in luxury real estate, where the wealthiest people in the world would pay huge sums for amenities, belonging, and above all, seclusion.

This attitude persisted after CrossHarbor, the Boston-based private-equity firm, purchased the Yellowstone Club in 2009. Since then, CrossHarbor has acquired Big Sky’s two other luxury clubs and, along with Lone Mountain as its development arm, expanded to luxury hotels like the Montage, where suites run to more than $7,000 per night. When Lone Mountain purchased all the undeveloped land in Big Sky’s Town Center in 2022, the deal put the developer at the head of the Town Center Owner’s Association, the TCOA, which plows the area’s streets, maintains streetlights, and performs other nominally public services. The acquisition gave Lone Mountain significant sway over new development within the TCOA’s boundaries—which happen to encompass what most people experience as the “beating heart of Big Sky,” as a Lone Mountain–owned magazine put it. The future of vacant lots or road placement: these decisions are now influenced by Lone Mountain and CrossHarbor.

In annual speeches at the Community Building Forum, Matt Kidd, a managing director of CrossHarbor and Lone Mountain, frames his firm’s expansion as inevitable, though at times he acknowledges dissatisfaction. “I have days where, and some of you would like this,” he said in 2022, “but I have days where, it’s like, we should stop building everything.” Ultimately, Kidd sees Lone Mountain as a benevolent force. Through philanthropic giving, the company supports many local organizations annually, and has built bike trails, a community center, and helped establish a medical center; the Yellowstone Club Community Foundation has donated nearly $30 million in Big Sky since 2010. “There’s a real town,” he said in another speech in 2020. “I mean, you can walk down Main Street, which you couldn’t do a few years ago.”

Physically, yes—there’s a commercial strip where, just a decade ago, buildings were interspersed with sagebrush. But as Alanah Griffith, a Big Sky local and a lawyer who has represented Big Sky HOAs, kept reminding me, “there is no town of Big Sky.” Instead, there are HOAs and private parcels, more of which have entered Lone Mountain’s sphere of influence in recent years. What Big Sky will look like in the coming decades will be notably sketched by “the main developer in Big Sky,” as Lone Mountain calls itself, operating properties using a tangle of LLCs, registered with the state using CrossHarbor’s Boston address, according to public data. Griffith, who is running for the Montana House seat that covers Big Sky, took clear delight in my struggle to understand her hometown. “Clear as mud, right?”

One morning last ski season, I woke early and drove to Ennis, one of the towns being flooded by Big Sky’s economic spillover. There seemed to be different weather in every direction—a black shelf of storm clouds covering the peaks above Bozeman and a turquoise sky ahead. The road took me through mountain ranges, into the Madison River Valley, and finally to Ennis, population 917. Western-style false-front buildings line Main Street, suggesting the gold-mining town it once was. Several famous trout-fishing streams bisect the valley; it is common to hear it referred to as a “drinking town with a fishing problem.”

I drove through Ennis and up a snowy road past the county airport to a large two-story structure, still under construction, with scaffolding visible through windows covered in plastic. Inside I found Luke Theriault and John Zeller, two local contractors who often work together, finishing a drywall installation. Zeller is tall, broad-shouldered, jocular, and has a Fargo lilt, while Theriault is laconic, with a bear-claw tattoo on his neck that alludes to his Anishinaabe heritage. Zeller came to Montana during the Great Recession to work on high-dollar houses, and Theriault followed. “What Luke and I were doing back in Minnesota was what we like to call shit-boxes,” Zeller told me, referring to cookie-cutter homes. The work near Big Sky was different.

They showed me around what Zeller called a “curious house.” A bathtub, planned for one corner of a loft with no surrounding bathroom, was set to face large windows looking out on the Madison Range. Over those peaks sits Big Sky. The most direct road from Ennis to Big Sky—absent a helicopter—is controlled by Moonlight Basin, a Lone Mountain development, and requires a pass, which sometimes costs as much as $100.

As we stood on the unfinished floor of the loft-to-be, Zeller told me that he and Theriault would work seventy-hour weeks, often on houses for homeowners from Texas or California that occasionally cost up to $62 million. Both fear the Montana housing boom will go bust, even though the wealth of their employers offers some comfort. Zeller talked about ballooning inflation, the lack of affordable housing, the price of diesel for his truck. “How is this sustainable?” he asked, gesturing outward.

When COVID hit, Justin Timberlake and Jessica Biel retreated to their Yellowstone Club property, and well-to-do, newly remote workers fled the coasts for Bozeman in droves. Formerly working-class neighborhoods have been remade. In 2005, the city considered an “urban blight” designation for a section of Bozeman called Northeast, where, in 2009, the average home cost less than $300,000, according to an analysis by Megan Lawson, an economist at Headwaters Economics. By March 2024, an 1,800-square-foot house in Northeast was valued at $825,000. Between the ever-present appetite for luxury homes in Big Sky and the post-pandemic real estate explosion in Bozeman, the demand for construction workers is virtually endless, a demand that has been met by a massive influx of immigrant workers, largely Hondurans and Venezuelans. I met one woman named Kendi, who now works framing houses for new construction projects in Big Sky. While waiting to cross the border, she sent her children ahead of her; they were held in a facility outside El Paso before the whole family made it to Montana. Some migrants arrive in Bozeman with ankle monitors, another longtime Bozeman construction worker from Mexico told me. “They cut it and throw it into the canyon,” he said. Without Social Security numbers or credit histories, securing housing on the open market is nearly impossible, and those without legal status are forced to the fringes, often living in apartments and mobile homes owned by construction bosses. “I’ve seen some guys—they live almost twenty guys in one place,” the construction worker said.

The immigrant workers tend to hold different jobs from the ski-slope employees, but some experiences cross these divides, notably that of having one’s employer for a landlord. Lone Mountain has spent more than $300 million on community housing and plans to build over one thousand more units. One of these projects is the Powder Light, a drab collection of stacked prefabricated boxes costing $1,700 a month per room, often shared, and backed by Lone Mountain; the 448-bed development was finished in 2023. A current Yellowstone Club employee, who had previously worked for the resort, was one of the first tenants, and he told me he experienced water pooling on the carpets and fuses blowing if the stove and oven were used at the same time. “Everything about the housing here is the most half-assed, cheaply built garbage that you can imagine,” he told me.

There’s an assumed trade-off here: the great skiing is supposed to make it all worthwhile. And while it’s easy to find workers with dark stories about Big Sky winters, many seasonal workers remain, as they might put it, stoked. Last February, I stopped by the Golden Eagle Lodge, a motel converted to workforce housing that is generally referred to as the Dirty Bird. I ran into Jethro Cormier, a stocky and ponytailed twenty-year-old lift mechanic, who told me that he came to Big Sky from Louisiana after dropping out of college. He loved the Dirty Bird, which he found preferable to Bozeman, where some resort workers end up in the Super 8. It might be, well, dirty, but if the heater isn’t working, the resort will eventually send someone to fix it. “I mean, all my friends are here,” he said simply. “It’s a great time.”

In the end, it may be true that life for young people is harder, more precarious, and plainly less fun than when the older generation of ski bums first arrived in Big Sky. “Twenty years from now,” Hart predicted, “you’re not going to have employees in this town.” But some traditions endure, such as the Dirtbag Ball, the annual end-of-season party after the spring-break rush. I ran into Hart while waiting to enter the bar that hosted last year’s Dirtbag, and she wore a red sequin dress and a fur wrap. Back in the day, she told me, the ball aimed for a mix of debauchery and high fashion, but today’s style tends toward neon ski jackets (and the occasional cowboy hat).

Every year, dating back to the Seventies, the resort’s ski patrollers vote for a Dirtbag king and queen. These honors go to great skiers and enthusiastic partygoers, those who answer the bar’s last call and greet the sun on the slopes the next morning. Winners must work regularly—no trust-fund kids, in other words. Dirtbag royalty comes with privileges: skiing off-limits parts of the resort, or first tracks on powder days, and never paying for drinks, of course. A former lift operator I met named Shane Knowles was crowned in 2010. He told me that it was an honor that also brought burdens on the body. “I say it was like the best-worst year,” he said with a laugh.

The evening’s band, Afro Funk, paused its set a few hours into the evening so that the outgoing king and queen could announce their successors. The departing queen clutched her drink and worked the crowd. “Show up for stuff and be part of the community, eh?” she shouted to cheers, then introduced her replacement, who she noted had “been shredding and partying for a long time.”

I found it difficult not to compare the event, long an underground affair, with the skijoring competition, which began in 2018 and seems by contrast a facsimile of an organic public festival. Citizenship is a hazy identity in Big Sky, so the ski town’s working class found other forms of community, of collective and earned self-expression. But skijoring and the Dirtbag Ball do share telling traits: Lone Mountain owns the skijoring track, as well as the bar where the dirtbags danced before me.

While reporting on and living in ski towns, I sense, at times, an ambient melancholy beneath the party atmosphere, a partial acknowledgment that the low pay, the bad housing, and the uncaring bosses will force many to leave. And while embracing being a dirtbag is a beloved way to endure this reality, the identity has always subtly played to the interests of the people who increasingly run these towns.

In Big Sky, there’s no sign that the forces squeezing the workers’ quality of life will end. International global finance sees Big Sky as an investment target. The One&Only resort, set to open next year, is backed by Kerzner International, the “ultra-luxury” hotel operator funded in part by the Emirate of Dubai’s sovereign-wealth fund. There are fourteen One&Only resort locations around the world, including in Cape Town, Montenegro, and the Maldives. For its first in the United States, Kerzner International partnered with Lone Mountain.

Change approaches from other directions. There’s been a fresh push to incorporate Big Sky, which could alter the unusual municipal arrangement that gives Lone Mountain and its private-equity owner such rare authority over the town. This effort faces many challenges, from what incorporation would mean for the availability of liquor licenses to the cost of the process. In his 2022 address at the Community Building Forum, Kidd took no public stance. “I don’t know if incorporation is the right thing to do or not,” he said.

The Yellowstone Club, meanwhile, is once again turning to the surrounding national forest to secure its future. Another Forest Service land swap is in the works, this one in the Crazy Mountains, where the Lone Mountain Land Company has already purchased an eighteen-thousand-acre ranch. On paper, the club’s part in the deal is minor: it seeks a small expansion of its private ski resort. But the other player in the swap is David Leuschen, a club member, a billionaire, and a large landowner in the Crazy Mountains. Montana public-land advocates say that the terms of the swap offer scant protections against large-scale development on the exchanged land. Leuschen’s relationship to the club, along with the club’s recent acquisitions, have led to speculation that the parties could develop their Crazy Mountain holdings in tandem—potentially creating a backcountry skiing paradise, available only to the few, on what was once public land. (A CrossHarbor representative said there are no plans for residential developments or heli-skiing.)

The wealth concentrated in this area can disguise itself, obscured just as much by LLCs and HOAs as by the physical walls around the Yellowstone Club. But for those who get a glimpse behind those walls, the view can startle. At a strip-mall coffee shop in Bozeman, I met a Honduran construction worker who described to me his long, harrowing journey to the United States, as well as good things about his new life, like getting to play soccer with his son during the summer. He builds houses at Spanish Peaks, he told me, one of Lone Mountain’s other private clubs. It’s very big, he said. Very big, he repeated. “The only thing I think,” he said, “is: How are there people with that much money?”