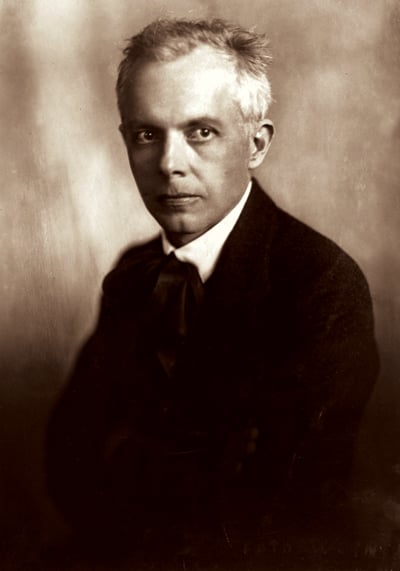

More than anything he looked like a man grimly in need of a transfusion. Béla Bartók had the pallor of a garlic clove. A wan, sometimes acrid personality to match. As obsessed as he was with tempo, you could have spent half an afternoon frisking his skinny little frame before you found a pulse. One of his closest friends would describe his voice as “gray and monotonous,” though he didn’t really have friends. His colleagues at the Academy of Music, in Budapest, found him bland: one of those almost offensively mild persons. He was sullen, puritanical, anemic, timid, like some mute and slippered monk shuffling the catacombs.

Sometimes the sweetish faint odor of chloroform could be detected when he passed by. He carried a vial of the stuff in his pocket to euthanize butterflies and other six-legged beasties that caught his eye while he wandered the countryside on one of his peasant-hunting expeditions. It was this hobby — chasing peasants, not bug collecting — that took him to Transylvania, skipping out on his teaching obligations for months at a time.

How the people there received him without snorting in his face one can only imagine: a klatch of bemused grandmothers, pausing from their work to regard this strange dink from the city, with his thin white hair and odd manners, come all this way just to meekly ask if they would sing for his pleasure? It must have seemed hilarious. But he was not as weak as he appeared. Surely, a few of the bábas noticed the powerful wrists beneath his threadbare cuffs. Wrists as strong as a butcher’s from hours of chopping at the piano.

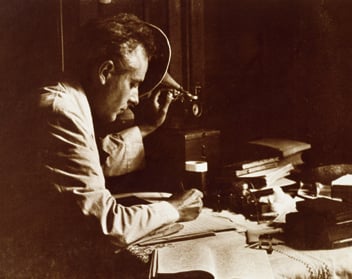

Of course, they marveled at the machine he had brought to suck the songs from their bodies. A szörnyeteg, they called it. “The monster.” He dragged it over the rutted roads of Maramureş and Székely Land, lashed to a horse cart. When he had them gathered round he would load one of the Edison wax cylinders, set the stylus on the groove, and demonstrate the device for them like a colonial officer showing the natives how the machine gun took the belt before mowing them down in their huts. Once he’d gained the trust of the hill folk, he would wait until the end of the workday, until the village maidens returned from picking apples, or haycocking, or whatever it was peasants did when they weren’t singing and getting drunk. Rapt, he would sit across from them in the lamplight. When they opened their mouths to sing, he lowered the arm, and the needle bit into the turning cylinder.

Like Rumpelstiltskin, he hurried back to Budapest to spin the bales of itchy straw into chaotic threads of Lydian gold. When audiences suckled on the usual Viennese milk heard his compositions, they fled in horror. If anyone still needed convincing that Hungarians were, indeed, a breed of Satan, as the Chanson de Roland put it, here was the barbaric proof. The gaunt sickly weakling — Herr Bartók — was transformed into a terrifying soul onstage. However meek he was in real life, here in the theater, behind his piano, he came to life. He leaped about the keys like a panther, like Menelaus crouching through the dark, spear in hand, creeping up to the wall. And then, between movements, during that excruciating pause, when some old fuck might be permitted his long withheld cough, you realized that, in fact, the blazing stare of the master was turned upon you. The audience had fallen away into darkness, and it was only you and the master. During this brief unreal moment, it felt as though you had become the subject of a new arrangement stirring in the composer’s mind. As though the whole time he had been playing, he had been hunting, stalking, and only now, when it was too late, did you realize he had smelled your blood.

Bartók House, Budapest. Embedded in the papier-mâché hills are little electronic peg lights that blink on when you press one of the buttons on the brass panel. Each light corresponds to a village where Béla Bartók collected. The mountains are built low to the floor, so you have to get down on hands and knees, like a child, to see, though I am the only one down on hands and knees. The mountains themselves, at first glance, look topographically sound. But they are a crude simulation, bald and artless, without so much as a single fake tree. It reminds me of the model-train layout my father built in the basement. He, too, had left his mountains unfinished. They were supposed to replicate the green hills that hugged our New England hamlet, where he was installed as resident village shaman, a.k.a., United Methodist pastor. He’d put a bit more effort into the village — the little church where he preached, the funeral home, the general store, even an elaborate complex of redbrick buildings that stood in for the sprawling campus of the Vermont State Hospital (formerly the Vermont State Asylum for the Insane), only a block from our house. It’s hard to convey the impact of growing up in a town where the main industry is the warehousing of the insane. Everywhere you turned were heavily sedated casualties, zombie courtiers with day passes from the castle. Sometimes, on my way to school in the morning, I would have to step around a patient on our front porch recovering from a walk, staring at a beetle crawling up his shoe. Behind the hospital was a smokestack that I once believed they used to dispose of the incurable.

After church, still in his robes and collar, my father would descend to his private dungeon with a mason jar of bourbon and amuse himself by arranging the tiny plastic figurines that wandered the grounds of the asylum to do perverse things behind 7 North or the B Building. I would discover them as I crawled around on the elevated table — the layout was five feet off the concrete floor, to accommodate his giant’s height — it being my greatest pleasure to frolic up there in my father’s clumsily composed world of HO track and switch towers, until one day I got too close to the ledge, slipped and fell, gouged my belly on the particleboard corner, and cracked my chin on the very real and unsimulated basement floor in an orgy of blood and pain. I still remember my father running with me in his arms across the yard, weaving through the intricate flower gardens kept by the dentist next door. I remember how the dentist’s fingers tasted of potting soil as they probed my bloody mouth. I’d bitten clear through my lower lip. I also remember the laughing gas — as if I were a gypsy moth the dentist had caught laying its ravenous eggs in his night gladiolus and then dropped in a vial of chloroform. I fluttered drunkenly upward, batting at the fluorescent panel as my legs kicked out in the air beneath me.

“És az utolsó. Most. Vége.”

“Yo, we’re going upstairs.”

This is the voice of my guide and translator, Bob Cohen. He and the director of the museum are already ascending, though I’m still down at floor level taking pictures of the toy Carpathians.

As we climb up to the second floor, the director, who wears a leather jacket and has buckles on his shoes, points to the banner in the stairwell embroidered with the entire score of Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto, his final piece, which he wrote in exile in New York City. The stairs go up one more flight, but then dead-end at the wall. The guide explains how this is because after the Third Piano Concerto, See? That was it. In fact, even after the ambulance had been dispatched to his fifth-floor apartment on West 57th Street, Bartók spent his last frantic moments trying to get down the final seventeen bars. The story goes that the ambulance men had to drag him away from the unfinished score. The dead-end stairs seem pretty heavy-handed, but the director is clearly proud of the symbolism.

On the second floor there is a lot of the weird furniture Bartók brought back from Transylvania. He furnished his whole house with the stuff. It’s all painstakingly carved and painted: geometric stars and what look to me like hex symbols and other hill-folk glyphs, somewhat oversized. Bob and the Hungarian are standing in front of a cabinet, laughing. The director points at a small box behind the glass.

“Our latest exhibit,” Bob translates. “Bartók’s last butt.”

I look in the case. “The last cigarette he smoked?”

“This is new,” Bob says.

I regard the little twist of yellowed butt, set like an engagement ring. The director talks quickly. “In 2006 they were doing a complete renovation here and called in somebody to work on the piano, this famous instrument restorer. He took the whole thing apart and found that inside.”

Idly, I wonder which string it was found under. Perhaps Bartók put the butt there on purpose for some kind of special effect.

“They checked — it’s a Tisza brand cigarette. [Hungarian.] And that’s what Bartók liked to smoke. [Hungarian.] So somehow or other it got between the strings of the piano. [Hungarian.] It was brought as a gift to his son.”

“That’s really beautiful,” I say.

Here and there are photographs of Bartók with his wife and children, one of the master in a polka-dotted ascot and suspenders, playing a giant crank instrument with strings and a primitive keyboard.

“Hurdy-gurdy,” Bob says. He takes his camera out of his leather fanny pack to get a picture. “Last traditional player died seven years ago.”

Bob is originally from the East Bronx via Teaneck, New Jersey, but he’s lived in Budapest for the past twenty-five years. His main thing is klezmer.  Not the honky-wonky clarinet-heavy wedding-band American klezmer. His specific niche: Carpathian klezmer. He spent years tracking down and recording the sacred, original stuff in Transylvania. Mostly his hunting days are over now. But he does have a band.

Not the honky-wonky clarinet-heavy wedding-band American klezmer. His specific niche: Carpathian klezmer. He spent years tracking down and recording the sacred, original stuff in Transylvania. Mostly his hunting days are over now. But he does have a band.

Inside another case we regard Bartók’s cuff links, stamps, a well-worn pocket metronome. If you read accounts by his students, you quickly learn how he put tempo, almost cruelly, above all else. He demanded a precision impossible to duplicate and would shame those who could not master it.

We wander over to a roped-off room. It is the master’s studio.

There is his coffin, black and shellacked. Did I say coffin? I meant piano. Black and shining, the track lighting sends streams, like rivulets of thawing ice, dribbling across the lid. The room is otherwise nearly empty. A leather chair by the window. The window is like any window. But the only thing of interest to me is the machine on the desk in the far corner.

“Is that the actual phonograph he collected with?” I say, sticking my head into the room past the velvet rope.

“NO NO NO.”

“Don’t lean over it,” Bob says. “They’ve got a sensitized alarm system.”

The amplifying horn is octagonal painted metal. The headphones rest beside it. Bartók’s son Péter, writing in his book My Father, describes how his father’s study was always inexplicably filled with flying insects. Covering the window, crawling on the walls. He wondered if, somehow, “perhaps the bugs felt safe near him.”

Bob looks at me. “Did you want to go closer for a photo or something?”

Yes I do. I am drawn to it. Though it does not appear they’re going to let me near it. The thing is, it is this machine, more than anything else, that allowed Bartók to become Bartók. His whole method relied on this advantage: to go out in the world, collect bits of direct experience, make faithful transcriptions, and then feed them to his inner gargoyle.

As a young man, he had not shown great promise as a composer. He was a good performer, was thought to have a brilliant career ahead of him as a pianist, but there was no burning inspiration to his early creative work. Of course, he was set back by the strange bouts of illness that had plagued him since childhood. (One skin rash that appeared at the age of three months lasted until he was five years old. The cure: arsenic.) During his first year at the Academy of Music in Budapest, in 1899, he began to vomit blood, and he was forced to take a half year’s absence to recuperate, in southern Austria. Aside from this deferred semester, and his general ill-health, his main impediment was no different from that of any young composer of his time. All were desperately hungry for something new. How tiresome his contemporaries had become with their endless copying of the Romantics. How pitiful their belief in Great Original Themes, especially when, really, all they did was turn out copy after copy of another Mendelssohn, another Brahms, another fourth-rate Beethoven.

Bartók turned to Wagner. He looked to Liszt. He profited by Debussy. But still he was starved for the new. After he attended the Budapest premiere of Also sprach Zarathustra, he thought he might have found the true, new way in Richard Strauss. “This work, received with shudders by musicians here, stimulated the greatest enthusiasm in me,” he wrote in 1902. “At last I saw the way that lay before me. Straightaway I threw myself into a study of Strauss’s scores, and began again to compose.”

It was as if he had climbed a mountain and been struck by lightning. He left the concert hall with his spleen glowing. For a time Bartók followed the new path blazed by Strauss and his chromatic tone poems. This seemed — it was — truly new.

And so Bartók began to generate a handful of interesting, alchemical pieces with inversions, rotations, retrograde inversions, motivic permutations. Overall they gave off the tonal whiff of dangerous laboratory experiments.

But it wasn’t until the summer of 1904, while Bartók was at the summer resort of Gerlicepuszta, in northern Hungary (now Slovakia), that he would overhear a nursemaid cooing a lullaby and discover his true master. He was there to work on his Piano Quintet. One day, he was interrupted by a voice from the next room. At first it must have annoyed him immensely. He insisted on working in absolute silence. In his studio, he muted out his noisy family with a thick leather blanket. In New York, many years later, he would leave the shower running as a kind of white-noise machine. But now, he set down his pen and sought out the girl.

She was flustered, faced by this fanatical wraith demanding to know what it was she was singing, and she must have been apologetic, no doubt thinking that she had disturbed him, for certainly the nursemaid had had to listen to his terrifying piano from morning till night.  But when she realized that he was not reprimanding her, only intensely curious, she told him it was just a simple song she had grown up listening to her grandmother sing.

But when she realized that he was not reprimanding her, only intensely curious, she told him it was just a simple song she had grown up listening to her grandmother sing.

Somehow Bartók found the courtesy and charm to persuade her to sing the song again so he might copy it down in his notebook. It was about an apple that had fallen in the mud. The song could not have been more simple. Bartók looked at it there, this apple in the dark mud, and he picked it up, and turned it this way and that, and he scribbled down the melody to better understand the shape of this thing he could not yet grasp. But where did the tree that dropped apples such as this grow? The girl told him she was from Transylvania. Her name was Lidi Dósa.

The encounter left Bartók wandering, confused, in a strange new orchard. Transylvania? It was a backwater — not a place one would ever think to turn for inspiration. More to the point: it was impossible that such music could still exist. Everyone knew — this opinion most confidently championed by Liszt — that if there was anything resembling a traditional Hungarian folk music it was the verbunkos preserved by the Romani, and that the peasants had long ago left their songs rotting in the weeds. And yet a few years later Bartók would set out there with a sack of wax cylinders and a phonograph in pursuit of this ancient form that in one afternoon had reshaped his entire mind.

But now the director won’t let me see the machine. At the very least I figure I can get a serial number. Bob looks at me like I asked to take the thing apart on the floor, or get a blood sample off the needle.

I ask the Hungarian if he is a musician himself.

“Igen, igen.”

“Yeah,” Bob says.

“What do you play?”

“Pianist.” Bob answers for him.

“Pianist?” I say. “Huh. You ever get to play that?” I nod at the piano on the other side of the rope.

“Kicsit, kicsit.” Little bit, little bit.

“When no one’s looking, I bet.”

The director shrugs, smiles, looks sheepish.

I give Bob a pleading look.

“Yeah yeah yeah yeah — I asked.” Bob crosses his arms. “He says that machine was, when he got it in the beginning of the nineteen hundreds, it was like, you know, the master super computer. They weren’t mass-producing these.”

“Do we know who manufactured this?”

“He doesn’t know,” Bob says.

“Is there a name on it, or . . . ?”

“He has no idea.”

“Maybe it’s an Edison?”

“He can tell you the typewriter’s a Remington.”

Bob is clearly ready for a cigarette. He listens to the guide and shrugs. “It might have been brought from Vienna.”

I recall reading a letter that Bartók wrote to Péter in June 1945, three months before the composer’s death, that began: “Waiting, waiting, waiting and — weeping, weeping, weeping, weeping — this is all we can do. For news has slowly begun to  trickle over here and these are rather alarming.” He had just read a newspaper report from Budapest that included an interview with his old friend, and fellow composer, Zoltán Kodály, who said that Bartók’s wax cylinders had been destroyed when Russian soldiers looted the National Museum.

trickle over here and these are rather alarming.” He had just read a newspaper report from Budapest that included an interview with his old friend, and fellow composer, Zoltán Kodály, who said that Bartók’s wax cylinders had been destroyed when Russian soldiers looted the National Museum.

It makes me think of the time I stood in my father’s neglected orchard, watching him burn all his papers. He had decided to do so on a whim, piling the back of his pickup with the dumped drawers of his filing cabinets, and I didn’t try to stop him as he pitched handfuls of his sermons into the fire. The last time I saw him, a week ago, he was still in the hospital. Still somewhere in the hangover of anesthesia after they’d torn open a hole in his stomach in a vain attempt to remove the tumor. But the black apple was stuck; it could not be plucked without killing him. He looked and sounded a million years older than he had before surgery and he still hadn’t absorbed that it had been a failure, but I did not have the courage to tell him. Even undead, my father retained his giant’s stature. During that last visit he had risen from the bed and was standing in the middle of his room in his flimsy paper gown, reeling and stammering, while two nurses hurried to wipe the shit that was smeared all down his back. I remember his look of bewilderment, and my own feeling of imminent collision with what I knew might soon enough be processed as reality. “Well, Dad, I’ve got to be going to Transylvania. Big magazine assignment. See you in a couple of weeks!”

In the elevator on the way out of the hospital I made a quick note to myself: You really can’t avoid this, you know. But by the time the elevator doors opened I was in Budapest at a bar with my New Jersey Virgil watching Serbian girls do Jäger shots.

Bob and the director talk for a minute. I think I make out the words dokumentum, fotográfia, gramofon, Amerika.

“You’d have to be a psychologist,” Bob says, in his indirect method of translation. “Here comes this city person, and the peasant who’s just going to sing for him has no idea what he wants, or how he wants it, you know? He just says, ‘Sing what you sing,’ and the — you’d have to be a psychologist to understand the relationship.”

The director looks infuriated at the idea of how messy it would be to get inside Bartók’s mind regarding the peasants.

“When he got married,” Bob says, “one of his academy colleagues came up and said, ‘Béla, I hear you have married again! Congratulations!’ and Béla answered, ‘Do not involve yourself in my genital situation.’ ”

We fall silent as a crowd of women come chattering down the stairs. Then we look at a few more cases. Bartók’s glasses. A child’s one-stringed toy fiddle, matches, keys, pencils, ink. A kind of forked instrument for drawing staves on composition paper, the handle of which is a stern little figurine of Wagner. Then we walk over to two glass boxes that lie flat like jewelry cases, and examine the contents. It is Bartók’s insect collection.

When I ask what his specialty was in bugs, was it just beetles or other insects too, the director, without really seeming to consider my question, says it was just anything. Nothing special. Just bugs.

Briefly, I try out my new digital-magnifying-lens app, which, really, is crap, but it does have a cool distorting effect, so, magnified eight times, the shriveled bugs look like giant quarter notes pinned to their vertical stems. I picture the composer sticking the wriggling notes to the staff before plinking out each tone on the piano.

As we’re leaving, Bob finishes recounting a final story the director told about Bartók walking in the park one day with his wife (I didn’t catch which one), when a big wasp flies past — zzzzzzzzzzt — and, either fearful of the bug or just testing her husband’s entomological savvy, she says, “Béla, what was that?” And he goes: “G-sharp.”

At the Institute for Musicology, which is housed inside Erdődy-Hatvani Palace, we are met in the rather grand lobby by the head of the Bartók Archives, a slight and genteel man who introduces himself as László Vikárius. I recognize the name from a journal article I found online called “Bartók’s Late Adventures with ‘Kontrapunkt.’ ” In his office, several flights up, there’s a large double casement window thrown open to a view of skeletal spires, river, general Gothic verticality. A pleasant breeze flutters the papers stacked around the room and on his desk.

Bob tells him how we’re going to be traveling through some of the same villages where Bartók himself went, and that we’ll also try to track down Lidi Dósa’s village.

Mr. Vikárius warms at the mention of Bartók’s muse. He says meeting the Transylvanian nursemaid was a small miracle for Bartók, as it led to the great discovery. “It was quite a revelation,” László says. “It was an accident that he heard this Lidi Dósa.”

“Do you know if she has living descendants still?” Bob asks. “We’ll be driving through Kibéd. I thought we’d stop and ask if there’s anybody who remembers if the family’s still there.”

The plan is to meet up in Transylvania with Bob’s friends Jake and Eléonore in two days. They’re driving from Moldavia, where Jake is working on a Fulbright studying links between Romanian folk music and klezmer. Bob speaks very highly of Jake, says he’s the best klezmer fiddler in the world.

“I don’t know about any relatives, but there might be,” László says.

“We could just ask in town,” I say.

“Ask the priest,” Bob says. “He knows everybody. A town that size — I’ve been to Kibéd, everybody knows everybody.”

László grimaces. “But let me tell you that it might be not so easy to go around and find someone. Or it might be too easy to find someone who appears to know something?”

Bob gruffly lets him know that he’s peasant-village street-smart enough to get us through any deliberate attempts at disinformation.

László returns to the subject of Bartók’s meeting Lidi Dósa. Just as groundbreaking as the accidental discovery of his autochthonous treasure trove of new melodies, László says, was Bartók’s discovery of pentatony.

“When he first reports on this discovery,” László says, “he mentions that he had found this ancient scale, which he had considered extinct.” Bartók also referred to it as a defective scale. “He didn’t have the right name for it. It was so new.”

“When he first reports on this discovery,” László says, “he mentions that he had found this ancient scale, which he had considered extinct.” Bartók also referred to it as a defective scale. “He didn’t have the right name for it. It was so new.”

“Defective scale,” I say.

“More ancient types of scales,” László says. “They are often pagan in origin.”

Nobody outside the hinterlands knew this music still existed, thanks to the geographic isolation of Transylvania — the very same geographic isolation that had preserved the music in the first place from the culturally polluting effects of the Ottoman and Hapsburg occupations. Even today, it’s an eight-hour train ride from Budapest to Cluj, the main city of Transylvania.

I ask László if it would be possible to see some of the Bartók Archive’s wax cylinders.

“Oh . . . ” László casts his eyes around the room. “They are — no.” He laughs. “I think that that is not possible now.”

From what I understand the cylinders are here in storage, and I imagine them lined up in a cool dungeon beneath us. Sadly, Bartók went to his grave (weeping, weeping, weeping, weeping) believing most of them had been destroyed in the war.

But László says it is not possible to see those particular vaults. Not today. (I later learn that the cylinders are kept at Budapest’s Museum of Ethnography.) But then he swivels in his chair toward his computer and says that if I want he can show me a few digital images. On the screen I see the words edison blank. The tin looks about the size of a can of Calumet baking powder.

When Bartók went on his excursions to Transylvania, he often went with Zoltán Kodály. It was Kodály who gave Bartók the idea of using the machine in the first place. Bartók recounts in his letters some of the tribulations of these early expeditions. Rain. Heat. Sickness. The coy obstinacy of peasants. The odd places he found himself collecting: pubs, boot makers’ workshops, pig-killing feasts. The cylinders themselves were very fragile. They had to be stored inside tin containers, and these in turn were stored inside padded boxes. The padded boxes were stored inside larger boxes to protect against the sinister roads. Edison had changed the formula from stearic acid, beeswax, and ceresin to a harder composite wax, so at least one no longer had to worry about cylinders melting in the farm-day heat. I recall listening to one of these early recordings at the library, and how in that moment I felt an almost unbearable suspense in the silence preceding the music. The hundred-year-old dead air being gently etched for posterity. A sound like a kind of grinding cosmic background radiation. You can imagine the brown wax cylinder turning. Bartók at the crank, waiting for his singer to gather her nerve as the needle carves its groove, the machine picking up the quiet apprehension of the country, the sound of its own turning, a bird, minuscule curls of wax falling to the ground and lugged off by ants to be archived in their subterranean grottoes.

When Bartók returned home he would spend hours, days, and years listening deeply and transcribing his recordings. It was critical to listen over and over, to get at all the shades and gradations.

“All of the ornamentations and the melismatics and stuff,” Bob says. “You wouldn’t be able to accurately notate that on one hearing.”

László nods. “And the original rhythms — there’s a logic behind them you can’t hear the first time through.”

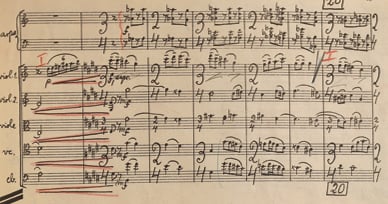

Bartók’s method was to first collect melodies, and then to classify the songs (Class A, Old Style; Class B, New Style; and Class C, Mixed Style), which he then broke up into subclasses of rhythm: I, Parlando (or Parlando-rubato), and II, Tempo giusto. Parlando being a looser kind of rhythm — a free rhythm reminiscent of natural speech. Rubato, meaning robbed, stolen from one note and carried over to the next. Tempo giusto refers to a stricter dance-like rhythm with the regularity of a steady heartbeat.

Bartók felt the rhythms of these “peoples living in primitive circumstances” were a kind of pure and spontaneous expression of instinct. He also admired how, unlike his own tradition of Western music, it was “void of all sentimentality and superfluous ornaments.”

It stimulated his own cool instincts.

Considering how long and repeatedly Bartók would have to listen before he had fully assimilated the peasant idiom into his system, he was lucky that Edison had included, on his latest version, the invention of both a pause button and a second key that, as Edison wrote, “when pressed down, will run the reproducer back so as to repeat anything which has not been clearly understood.” As much as the phonograph itself, it was these two innovations that enabled Bartók to make his close studies — to focus on the smallest intervals, to eavesdrop on these fragments of sonic experience like a scientist, to pause and rewind.

I’m still disappointed that I can’t fondle one of the actual cylinders, for the acquisition of tactile details and what all, but then László rummages around in his desk — “if you are interested, and I’m sure you are” — and then swings back around in his chair.

“Bartók made short transcriptions,” he says, holding something small and old and leather-bound. “He had such small-sized music books, which he could carry in his pockets.”

“These are his originals?” Bob asks.

“These are, yes, this one is original. Especially with vocal music, he notated on the spot.” László points at the quick mosquito notes in the master’s own hand. “You see here? He put down the melody and made some remarks. He carried around these books wherever he went on his search for new material.”

László says again how unusual the rhythms were that Bartók discovered. How he took this rawer thing and put it into his own music and how the first city audiences to hear it found his humping, thrusty peasant rhythms too “barbaric.” But isn’t this how the blood flows? With pulsing and barbaric and interminable fury. Melody is only a flimsy negligee, barely concealing the nakedness beneath. Why not rip off the lace and put one’s mouth direct to the wound — feel the blood pulsing straight from the source?

As much as I would like to be unafraid to come into such contact with that kind of raw direct experience, I now find that the nonvirtual presence of the diary balanced on my thigh, and the growing desperation for it to be gone, is triggering all the usual symptoms. My mind is playing, in scattered, rapid, broken sequence, through all its defective scales. I have been synchronized against my will with a demonic metronome. I feel its pounding rhythm inside my own abducted blood cells. And then, before I can stop it, I realize I am standing up from my chair and walking over to the window — or rather I perceive part of me doing this, like that hokey special effect you sometimes see, or used to see, on TV, where a  character is nodding off in a chair and then his sleeping ghost peels off from his body, stands up, and walks away from the oblivious prattling wife, cue laugh track, and this is what I now view myself doing: I watch my clone wander across the room while Bob and László discuss how Hungarian nationalism may have put Bartók in a mind-set of receptivity vis-à-vis the peasants, whereas prior to this new sense of national identity, as Bob puts it, they just weren’t considered; they were invisible. Then I watch myself jump out the window.

character is nodding off in a chair and then his sleeping ghost peels off from his body, stands up, and walks away from the oblivious prattling wife, cue laugh track, and this is what I now view myself doing: I watch my clone wander across the room while Bob and László discuss how Hungarian nationalism may have put Bartók in a mind-set of receptivity vis-à-vis the peasants, whereas prior to this new sense of national identity, as Bob puts it, they just weren’t considered; they were invisible. Then I watch myself jump out the window.

I wake from a dreamless sleep with strange bugs crawling over my face and the screech of train wheels. I swat off the flies and sit up in abrupt panic to see Bob across from me, hunched over the little foldout table, in our private berth, hacking at a log of salami. He’s working with a butterfly knife, cigarette dangling from his lips. When he’s finished slicing, he completes his task with a quick but elaborate sequence of one-handed flips to close the knife, pockets it, and then gives me a hunk of cheese and bread and says we’re about to cross into Romania.

We eat in silence while the landscape rattles by and I unsort myself from sleep, trying to remember why I am here.

“I don’t think they really give a shit if you smoke,” Bob says, wiping off his fingers and standing to flick his ash out the open window. Insects cling to the dirty pane. “You’re not supposed to smoke, but this is the train going east. This is a second-class old commie train.”

I make a note to take a few pictures of the engine for my dad, a lifelong train spotter. Some men collect folk songs, or pictures of birds, or postcards of dungeons; my father collects images of diesel-electric locomotives.

Bob continues talking as if I have not been asleep.

“He didn’t try to break the thing in pieces and then fit them in the box. He made the box fit the original.” It takes me a minute to realize he’s talking about Bartók. But at the moment it’s hard for me to summon even a semiquaver of interest.

Bob’s not usually a tour guide. His klezmer band, Di Naye Kapelye, plays shows throughout Europe. On the side he teaches fiddle workshops and writes the occasional piece for Time Out: Budapest. In his spare time now he’s trying to back up all the old cassette recordings he made on his ethnomusicological sprees into Transylvania.

“To be safe I burn CDs and make digital files of my recordings, which Bartók never had to do.”

When Bob and I first made contact he was finishing work on a book about fishing for catfish called Catfish Fishing. He wrote another book, for young readers, called Transylvania: Birthplace of Vampires.

Many people are surprised to learn that a place called Transylvania actually exists. Transylvanians are often just as surprised to learn that many people think that their homeland is a fictional creation filled with monsters.

Bob first came to Hungary to visit relatives a few times as a young kid, in the Sixties, then again in 1972, when he was fifteen. He got turned on to the folk-music revival and the táncház, or traditional dancing, movement.

“It blew everybody away. It was like hearing raw folk music for the first time, you know? I said, This is the stuff I want. My uncle was like a very peasanty butcher, and he would take me around to people he knew who played music. The next-door neighbor played the citera, another neighbor played the flute, the garbage men were  Gypsies, they had violins in the back of the garbage truck. He bought me a violin, and he bought me these three records that were Hungarian folk music. I went back to the States and I just fell in love with it.”

Gypsies, they had violins in the back of the garbage truck. He bought me a violin, and he bought me these three records that were Hungarian folk music. I went back to the States and I just fell in love with it.”

He returned the following year and spent three months hanging out in Gypsy bars. In 1988, when he was thirty-two, he came back to stay. He got work teaching English and married a woman whose family was from Székely Land, the region of Transylvania where Lidi Dósa lived. Bob says he knows a lot about the Székelys, and not only because he used to be married to one. He currently lives upstairs from a Székely family who are forever doing what they love best: arbitrarily drilling holes in the walls in an eternal but fruitless quest to make the apartment buzzer work.

At the moment, Bob’s big-money scheme is to write a Gypsy-vampire detective story set in Cluj, which is where we’re headed. I ask Bob to clarify the role of Romani musicians in the music Bartók collected.

He lights another cigarette and the smoke leaks through his teeth as he talks. “After the Turks had abandoned Hungary and Transylvania, the Gypsies, who had played Turkish music, without any chords, now played music for a new military patron class, which was the Hapsburgs — the Hungarian nobles, the occupying forces. And they did this with the new modern Western instruments, the violins and stuff.” Music for an upper-class taste. “You had to have money to go to a fine inn to pay for those good musicians. The local Gypsies would play for both the local nobles in the countryside and to the peasants.” The interesting thing, he says, is that the closer you got to upper-class society, the closer you got to harmony. The melodies were harmonized and resolved, whereas the music played by peasants in Transylvania put more of an emphasis on rhythm. “So instead of going up to a minor and then to a seventh and then something . . . you’re basically doing a rhythmic drone with the major chords of the melody in there.” His teeth smoke. “And it became an entire style.”

“That rhythmic drone,” I say.

“Yeah.”

He says he’s taught classical musicians, trained in conservatories, who wanted to learn how to get that sound. “And they’re fixing the melodies. The melody doesn’t want to be fixed. It’s got this incredible tension, you know? You completely harmonize it, you make it banal. And that’s what we were talking about with Bartók. He knew how to set a folk song to classical music but still maintain the spirit of the folk song.”

We look out the window and see some farmhouses and he says once we’re in Transylvania proper I’ll see the giant homes some Romani now build after stints working abroad.

“They build these McMansions to show off their wealth, then shit out in their back yards with the chickens because they’re disgusted by the idea of indoor plumbing.” He brushes ash off his lap. “They hate the idea of shit-water going over their heads. The New York Gypsies can’t stand the idea of gadjos shitting over their heads, so they won’t live in high-rises but move out to Queens where they can buy all three floors and shit in the basement.”

The men, he says, are unfailingly polite around women, even if they are just as vulgar as any men in unmixed company. They don’t say “I have to piss” if a woman is around, they get all genteel, Bob says in a fake-genteel voice, and say, “I must go water the horses.”

He says this as if it’s the summation of years of anthropological work.

When we finally meet up with Jake and Eléonore, at the hotel in Satu Mare, they’re eleven hours late. Bob and I waited at the station for a while, where they were supposed to pick us up, but we finally gave up and took a taxi to the hotel. They seem haggard when they arrive, well after dark. Jake had opted for what he thought would be the shorter national road (N17), despite Eléonore’s insistence that they stick to the safer European road (E58). Soon they were bottoming out in potholes the size of koi ponds; Eléonore says she begged Jake to turn back, but he pushed on until she made him stop to speak to a police officer who told them, with a great smirk, that the road only got worse and at the rate they were going (it had taken them one and a half hours to travel nine miles) it would take an extra day to get to Satu Mare. So they turned back to the highway and then nearly hit a Romani kid who was jumping into the road to scare drivers.

When they join us on the patio for drinks, Eléonore is still shaken, and she says she was angry with Jake for not listening to her, but the way she says it, in her light, whispery French accent, it is hard to imagine her being truly mad.

The next morning we pack up the violins and bags, and all of us cram into Jake’s ’96 VW Golf. It’s claustrophobic being pinned behind Bob’s somewhat forbidding bulk, but I feel well compensated by getting to have Eléonore as my backseat companion, with her faint but pleasing French-girl accent (et stink). She keeps a secret stash of chocolate and every once in a while breaks off a square and slips it to me.

As we travel farther northeast my mood lifts, as it always does in the mountains. Transylvania really does look and feel a lot like Vermont. Granted, with medieval trappings: the humble wooden cottages, the van Gogh haycocks, the bored peasant women sitting on rickety stools silently casting hexes on us. There are fewer cars and more horse-drawn wagons driven by brawny, sun-poached men in funny little hats. (Never make fun of the funny little hats, Bob says. They’re  a symbol of male virility.) As yet we see no forbidding castles. But we are in rural Maramureş, in far northern Romania, the most remote corner of Romania, quite possibly the most remote corner of non-Arctic Europe. We pass a few of the McMansions Bob warned me about, all pink stucco balconies and tacky clerestories. I see one with driveway gateposts crowned by two painted (photorealistic) concrete German shepherds.

a symbol of male virility.) As yet we see no forbidding castles. But we are in rural Maramureş, in far northern Romania, the most remote corner of Romania, quite possibly the most remote corner of non-Arctic Europe. We pass a few of the McMansions Bob warned me about, all pink stucco balconies and tacky clerestories. I see one with driveway gateposts crowned by two painted (photorealistic) concrete German shepherds.

“I fucking hate dogs,” I say.

Eléonore takes pictures out the window. “The old women are so beautiful,” she says. Even if I think all the old women really look like they’re in eternal mourning, everything Eléonore says sounds true. It’s the confiding pianissimo of her voice: not shy, but the kind of voice you could find your way to in the dark.

I want to tell her about my father, and how I got drunk with his moderately likable dog the night following his botched surgery, but I keep this confession to myself, feeling that it is somehow shameful to share one’s dead, perhaps especially when they are not yet actually dead.

As for Jake, I do confess feeling a bit awkward having this virtuoso chauffeur me around Transylvania. It seems it should be the other way around. But he’s super easygoing, despite what I sometimes interpret as his slightly menacing mien in the rearview mirror, an innocent defect due only to a childhood cleft lip. He’s a master at circumnavigating the potholes, which can take up an entire lane — as if a giant beagle had come down from the mountains and dug them up willy-nilly in its stupid instinctual hunt for bones.

Jake and I hit it off soon enough over Milan Kundera. I’ve brought The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, which turns out to be Jake’s favorite novel.

Kundera, I tell him, leaning forward between the seats, I confess, to better study the canine curl of his lip, wrote that Bartók’s music was “hypersubjective.” And that his “soul’s sorrow could find consolation only in the nonsentience of nature.” Fortunately for Bartók he had his machine. The nonsentient monster-machine that let him extract what he needed from people.

Come early evening, we arrive at our pensione in Poienile Izei. It’s down a long dirt road, deep in the countryside. In the front yard is a gazebo and a tree covered with pots and pans, which, according to Jake, means a girl of marrying age lives here.

Beneath the tree is a swinging bench upholstered with a tattered heavy sheepskin, and outside the barn across the yard is a wooden rabbit hutch.

“Ooh,” Bob says. “I hope we’re having bunnies for dinner. Cute things always taste good.”

“Ooh,” Bob says. “I hope we’re having bunnies for dinner. Cute things always taste good.”

After we get cleaned up we reconvene in the main house, where our hosts, a married couple in their sixties, have put out a feast on a long table. Bob takes pictures of all the food to blog about later. He’s on the Atkins diet but is making an exception for the heaped plates of plăcintă, a delicious cheese-stuffed fried pastry; mămăligă, basically polenta, but mixed with more cheese, plus crumbled bacon; and ciorbă, tripe soup. It’s not cute, but it tastes good.

The house is simple and clean. Hanging from the back of the front door are bags and purses made by the wife from the wool of their sheep. A picture of Mary and baby Jesus hangs on the wall next to a poster from a local tourist agency. The poster shows a few sites of unlikely interest. There’s the Romanian Peasant Museum in Bucharest, so, really, not so local. But then there’s the village of Sârbi, where the main attraction is a miller named Gheorghe Opris who makes miniature ladders out of plum wood, which he then inserts into bottles of pálinka (fruit brandy), like model ships, as if there were any way one could climb out of a bottle of fruit brandy.

Bob picks up my iPod and asks how many hours of recording I can get. The app I have gets thirteen hours of uncompressed audio per gigabyte, but at a lower quality setting, I could get as much as 130 hours, which, if you consider that the cylinders Bartók was using got four minutes each, would be the equivalent of 1,950 wax cylinders. How many horse carts and how many trips from Budapest to Transylvania that would take, I do not know.

Bob no longer burdens himself with machines. On earlier collecting expeditions to Transylvania, to get to the underlying original-original holy-holy stuff, he used to always bring a Sony Walkman. He went through about six of them. Once, in a bad situation, he had to buy a Panasonic to make a last-minute recording of a peasant fiddler who knew some Jewish tunes from the 1930s that he wanted.

One time the Jewish Music Study Group at Budapest’s Eötvös Loránd University gave him a Marantz to go to the village of Ieud to record the late Gheorghe Ioannei Covaci and his family, who, according to Bob, had the greatest repertoire of Jewish instrumental music of any Romani family in Transylvania.

“I carried it in my backpack and got to Ieud via trains, hitchhiking, and walking. After a couple of weeks I was in agony. It was heavy, especially with the big microphones. A pain to set up. I think this is how I screwed up my back. And when I got to Ieud, Gheorghe’s son, Ion, the accordionist, had an eggplant growing out the side of his face.” Bob makes a grotesque hand gesture over his face. “An abscess. So I gave Ion money to go to the hospital in Sighet — and as Gypsies are wont to do, the whole family, minus eighty-five-year-old Gheorghe, accompanied Ion to support him in his hospital stay, leaving me with no orchestra to record. But I got to sit with Gheorghe for a month, learning style and tunes and recording some pieces.”

In this way he built his repertoire.

“The other bands are almost all working with material that comes from Grammophon records. My band is the only band who’s only really worked off stuff we’ve recorded.” Bob picks up a bottle of pálinka and pours himself a shot. “In order to be legit, we’ve got to get down here in the mud.” He drains the glass and goes outside for a smoke.

After a little while a neighbor shows up with a guitar and then our hosts, both mister and missus, reappear dressed in traditional peasant garb. The man has a violin. When they start to play it’s all rather startling. The violin is beautiful and strange, yet somehow at odds with the guitar, which the neighbor plays with a rough, senseless kind of rhythm. The neighbor is several heads taller than our hosts, lanky, gold of tooth, and ruddy of face — he beams like a drunken butcher. He holds his guitar not at all like a guitar but propped sideways on his hip, with the neck straight up, the headstock nearly grazing the low kitchen ceiling. I make out two chord changes, tops. I think the guitar is actually missing a few strings, but he beats on it as if trying to bludgeon the smaller man’s wimpy, scurrying melody. His strumming sounds like roof work.

Despite the violence of the guitar, the wife, who wears a rose-patterned skirt and a green-and-black head scarf and little booties at the ends of her bare calves, each of which is as thick as a piglet, sings, her fists on her hips, and in an instant her high, lonesome voice dispels what I have not until this moment registered in myself as homesickness.

The woman’s song has a sense of defiant pride, and when I feel her warm spittle fleck my cheek I feel happy for this small if accidental intimacy.

The men’s outfits are far more interesting than the woman’s. They wear those little hats we’re not supposed to make fun of, and white blouses cinched at the waist with giant black leather belts that, not to be funny, nor to make fun, but only to accurately describe, look very S&M (i.e., three buckles), but that, I suppose, must be some kind of back support for lifting sheep. I recognize the outfit as that worn by the fearful peasant coach drivers who refuse to take the hero across the bridge to the castle in F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu. What Murnau could never have captured in black and white, however, are the dazzling multicolored ribbons on their hats and the mint-green hearts, each the size of a locket, embroidered around the flowing flared cuffs of the mad guitarist’s sleeves.

Soon, Jake and Bob get out their violins, too, and the small kitchen is reverberant with music. Eléonore sits close beside me with a glass of pálinka and translates the woman’s song. The words have to do with how the world is big but she doesn’t have any room in it. Mare-i lumea şi nu-ncap. And how when you’re doing well in life people really aren’t glad for you. Ca aşa. This is kind of the way it goes, she sings.

When Jake plays, they watch with amazement. That this American boy with the leather jacket and the cleft lip can play this music, their music, not just Romanian music, foarte frumos, so very beautiful, but their music, the style of Maramureş. With the sphincter-clenching rhythm of Maramureş. They request something that might be traditional American music. Jake hesitates, laughs. You can sense the hosts wondering whether we have such a thing, and then Bob lifts his fiddle to his shoulder and starts in on some chicken-in-the-bread-pan-pickin’-out-dough barn lick, something from Hee Haw, and the woman cries bravo, frumos, so beautiful, and the drunk with the guitar smiles widely to reveal his terrible gold teeth and says it reminds him of the movies. He says that Bob’s playing is barbateasca. Da, the other man agrees, barbateasca, aşa! It is very manly, this Hee Haw music.

I try to imagine Bartók here, in his wool suit, eating stomach soup and turning down pálinka, teetotaler that he was, but how, really, the peasants probably never would have invited him inside their home, asking him to wait outside instead with the rabbits and his weird machine.

When Bob and the guitarist and I wander outside to the gazebo to smoke, we leave Jake and the old couple inside still playing, with Eléonore sitting at the kitchen bench looking melancholy or maybe just tired.

We sit across from one another in the dark and I can see the guitarist’s gold teeth gleam dully in the moonlight, like the pots and pans drooping from the branches of the tree. It’s cold and the air feels like a New England night.

Bob tells me, after the neighbor rattles on a bit drunkenly, that the man is glad I came here to hear the pure, authentic Maramureş music. He is proud of his music and happy that Bartók sought it out and borrowed it for his own nobby high-art purposes, but less happy now that it is being stolen and commercialized and distorted, made less pure by less pure hearts. He says they come with computers and steal their beautiful Maramureş music. He says he’s heard himself pirated on the radio, heard his own music mixed and dubbed into popular music for the discotecă.

“Our tradition is being lost,” he says. “But it will not die.”

One of the song forms Bartók discovered in this region was the hora lungă. A defining characteristic of the hora lungă is its “indeterminate content structure.” It is so ill-defined, so non-constrained, that it can remain what it is and yet be something else at the same time. The musician who takes up the hora lungă is free to roam, to compress, distort, stretch, quicken, or altogether break the rhythm, shatter the box, chase the hens out of the coop, and yet somehow it will always come back to being hora lungă.

The next day, in Ieud, we stop off to see an old woman Bob knows whom he once paid a hundred euros to clean a dress. He and his girlfriend, Fumie, had been traveling through on one of his collecting expeditions, and somehow she besmirched her dress. Bob doesn’t say how. I’m sure it was innocent. When we get to the old woman’s house she and several of her friends, all clad in the standard old-Romanian-lady regalia — layers of aprons and floral-print skirts, ratty sneakers, tan and polka-dot head scarves — are out in her yard, in the middle of preparing a meal for some kind of cemetery ritual, and right away the old woman and Bob — the old woman’s name is Nitsa — are laughing about the dress, oh yes the dress! There’s a table set up on the lawn by the kitchen door where Nitsa is molding balls of rice and her friend is beside her chopping peppers and the other women stand around a giant cooking pot with the rice and cabbage. The friends know about the dress, too! What a classic moment! You washed it. A hundred euros. The dress! Yes! Bob introduces me to Nitsa, says how I’m interested in Bartók. She wipes off her hands, reaches somewhere down into her aprons, and comes back holding a photograph of Bartók, as if she’s a wizard who reads minds, or maybe Bob called ahead, I don’t know. She holds it up close to my face and I can smell the old woman on the photograph. Onion. Paprika.

All the women’s arms are slicked to the elbow with oil and rice and tiny cubes of minutely diced vegetable matter. The eldest, who looks to be about 200, sits for the most part silent and motionless on a red box beside the giant pot, which is itself balanced on a small stool.  Her heavy forearms are crossed over her lap, creased palms turned limply up, here but yet not entirely here, watching but not watching. The others chatter and bicker while they work, tossing pinches of spices from glass jars with screw-top lids, answering Jake and Eléonore’s polite questions about what it is they’re preparing anyway.

Her heavy forearms are crossed over her lap, creased palms turned limply up, here but yet not entirely here, watching but not watching. The others chatter and bicker while they work, tossing pinches of spices from glass jars with screw-top lids, answering Jake and Eléonore’s polite questions about what it is they’re preparing anyway.

“Orez, varza verde, ceapa verde, paprica, morcovi, piper, cimbru . . . Nu carne.”

No meat. They are making sarmale, stuffed cabbage. Bob says it’s for a potluck for the dead. There’s a ritual in the cemetery in which the villagers bring dishes, the priest blesses the food, and then there’s a feast. I think of the cemetery we visited this morning to see a UNESCO-preserved wooden chapel where there was one old woman on her knees stabbing a giant knife into the dirt around a grave, chopping weeds and stuffing them into a tattered plastic grocery bag, and then the insane pornographic images painted on the walls inside the church, sinners being punished by devils armed with red-hot pokers and hammers and stakes and a lot of ultraviolent ass play, and I’m starting to feel like maybe Transylvania deserves its reputation.

Bob says if we’re lucky Nitsa will invite us in to hear her sing. She knows some of the songs Bartók came to collect. The photo of Bartók, it turns out, is a calling card from a French filmmaker who came through a few years ago shooting a documentary about Bartók that was never released. It’s quite possible Bartók stood in this same yard, watching a group of peasant women with tough, fat arms glistening in the afternoon sun. Eléonore is walking around the barn, taking pictures, her long calves encased in mint-green leggings. She looks at me looking and smiles. There is nothing I would like to do more than take her behind the haycock and stroke her mint-green calves, if only because it might soothe the stabbing sensation in my brain. The old women try out her name and possible Romanian variations. El-ee-nora. Eleonora. Leana! They try Romanian diminutives. Elena. E-lee-o-no-ra. E-le-o-no-ra. Ileana. Eléonore looks over and says, in her soft French whisper, “Ileana, e bine aşa. Ileana, da.” All around us in the yard: the sound of insects and their terrifying erotic infinite serenade.

It occurs to me again, as I watch a rooster waltz across the yard and snatch up a grasshopper, that there is something vaguely insectoid to Bartók’s music. Especially in the Third String Quartet. The chirp-bark harmonics, chanty rubbed-out rhythms. Pizzicato of grass blades plucked. To check out this hypothesis, I slip on my headphones to play a few measures. But as soon as I hear the familiar opening bars, the acid chisel biting down lightly on the metal lathe, the music hijacks the whole scene, which I guess I knew it would, and everything goes lurid and celestial but mostly just ur-level ominous.

It occurs to me again, as I watch a rooster waltz across the yard and snatch up a grasshopper, that there is something vaguely insectoid to Bartók’s music. Especially in the Third String Quartet. The chirp-bark harmonics, chanty rubbed-out rhythms. Pizzicato of grass blades plucked. To check out this hypothesis, I slip on my headphones to play a few measures. But as soon as I hear the familiar opening bars, the acid chisel biting down lightly on the metal lathe, the music hijacks the whole scene, which I guess I knew it would, and everything goes lurid and celestial but mostly just ur-level ominous.

Somehow the music has profoundly slowed the projection of the 200-year-old woman’s face into my head, and she now comes to me as if she were a video installation, put here for my exclusive contemplation, very much as if she had been set on pause. The deeper I sink into her creases and grooves, gripped by the horror wending into my ears, the more I hear what the musicologist János Kárpáti, in his analysis of the Third String Quartet, called the “primordial figure emerging from the . . . static harmony” of the first movement.

The figure, as described by Julie Brown in her monograph Bartók and the Grotesque: Studies in Modernity, the Body and Contradiction in Music, is more that of absurdist monster or chimera, a hybrid grotto-dwelling creature, a distorted fusion of the mechanical and the animal.

“In Bartók’s Third String Quartet we might understand the eruption of the Seconda parte into glissandi . . . and particularly the extremely wide, contrary-motion glissandi . . . to be a type of string grotesquerie,” Brown writes.

Just as the human body can be washed, clothed and contained within norms of social decorum only to erupt in defecation, urination, sex and disease, so the beautiful violin can be mastered and practised to high art standards only to erupt into glissandi, fiddler style and earthy scraping sounds. Sonic eructations might be compared with gross bodily functions and linguistic vulgarities.

Theodor Adorno also refers to the alchemical, mixed-media nature of the work in his review of the Third String Quartet, published shortly after its 1929 premiere:

What is decisive is the formative power of the work; the iron concentration, the wholly original tectonics, so precisely suited to Bartók’s actual position. Hungarian types and German sonata are fused together in the white heat of impatient compositional effort; from them truly contemporary form is created.

At the time, Adorno was a fawning disciple of Alban Berg, whose Lyric Suite was a major influence on Bartók’s Third String Quartet; Bartók began composing it just a few months after attending a festival in Baden-Baden at which the Lyric Suite was performed. Bartók had debuted his recently completed Piano Sonata there, then reported to his mother, in a letter dated July 22, 1927, that earlier that evening he had witnessed a demonstration of the new film technique of synchronizing voice to image. The big surprise came after dinner when the spectral image of Schoenberg himself was projected on the wall. Who remembers what he was talking about, but his voice and mouth movements were perfectly synchronized. It was uncanny. Bartók thought the sound equaled that of the best gramophone.

He was less enthusiastic about the medium years later, when his son Péter persuaded him to go see Fantasia in New York. He was unimpressed with Disney’s “experimentation with three-dimensional sound.” This was in 1943, when Bartók was dying, impoverished, and living in the apartment on West 57th Street. They went to see it one winter’s night, at the Little Carnegie Playhouse. They got through Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but after a bit of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, Bartók turned to his son and said: “We will go now.” At first Péter thought it was because his father was ill, but on the walk home his father revealed that he was upset because

a small segment was missing from the Beethoven symphony, it was cut from the film. My father could not tolerate tampering with artistic creations. “Why did they do that to Beethoven? If the piece was too long for them, why did they not pick something else, shorter? How could Stokowski permit it?”

Suddenly Bob is in my face, making the exaggerated, muted charade motions of a person removing headphones. He is yanking me out of my private theater — just as Papa Bartók yanked his son out of Fantasia — but still I remove the headphones and follow him and the others inside the house, leaving my digressions behind. We go down a long, dark hallway, following Nitsa, and emerge into one of the more bizarre rooms I have ever seen.

It resides at the center of Nitsa’s house. A room filled with vibrant upholstered pillows and carpets and tapestries of sheer floral pandemonium.

“It’s like a bad acid trip,” Bob says. It sounds like an exaggeration to say so, but you nearly can’t tell where the floor ends and the psychedelic rugs hanging on the walls begin. It gives me instant vertigo and is disorienting enough that when no one’s looking I pop a benzo.

“It’s called the clean room,” Bob says. “In Romania it’s the room that shows stuff off. You can greet people and bring them in here for a coffee, like, before you go to church. It’s not really used for much. This is like the living room that has the plastic over everything.”

All the tapestries are handmade, and when they make them, they always make a copy. Bob points to one and says that he himself owns the twin.

In the center of the room, on a table with a basket of hand-painted Easter eggs, Nitsa sets out five glasses, and then goes to the closet and comes back with a big plastic jug. Evidently it’s moonshine time. If I’d known I might not have popped a tranquilizer, but on the other hand, that’s never much stopped me in the past.

At first she refuses to sing, despite Jake and Eléonore’s pleas. This is something Bartók certainly complained about, how suspicious everyone was, and how nobody wanted to sing and how he’d have to cajole and beg and then they’d want money.

But after a few glasses she begins to sing a song about those who abandon the church and die, performing for Jake and Eléonore, who cuddle on one of the weirdly upholstered benches.

“This is the real folk shit,” Bob murmurs my way. “This is like hearing Robert Johnson.”

The pálinka is wonderful, even if my eyes get a bit crazed by all the demanding patterns until I find a place to rest them, on a painting of Jesus. He’s in a scarf-draped frame, with a powder-blue robe, a Vandyke beard, and he seems to be resting his eyes on me as well. He points to his heart, which floats just outside his chest, clinched by a chaplet of thorns like it’s wearing an ankle monitor. After a little more pálinka, I can feel my own parolee’s heart loosen. Free to wander on my leash, but not too far.

Bartók’s handwritten score for Hungarian Folk Songs © De Agostini/A. Dagli Orti/The Bridgeman Picture Library

As she sings I watch a fly crawl across Jesus’ face, which makes me feel inexplicably ecstatic. The Easter eggs sparkle in the sun that pours through the curtains.

Nitsa pours more drinks and then starts to sing to her glass. Palincuta te iubesc, mai dorule mai . . . “Dear Pálinka, I love you, hey my dear hey, but I drink you as long as I live, hey my dear hey! Because if I die I won’t be drinking you, but the ones who are left will drink, hey my dear hey . . . ”

She stops, pours more, we toast and drink.

Eléonore asks if it’s made with apples.

“De mere, şi de poame,” Nitsa says. Apples and berries.

“Mulțumesc.”

“Thank you!”

“Cu plăcere.”

“Foarte tare.”

“Very strong.”

“E foarte tare?”

“It is very strong!”

Then Eléonore suddenly disappears with Nitsa for a costume change. When they return Eléonore is blushing and awkward and decked out in an embroidered peasant dress, a black felt vest, and a white blouse with flared sleeves.

Then Eléonore suddenly disappears with Nitsa for a costume change. When they return Eléonore is blushing and awkward and decked out in an embroidered peasant dress, a black felt vest, and a white blouse with flared sleeves.

“Țărăncuță,” Nitsa says.

Bob looks at me. “Țărăncuță. Peasant girl.”

“Cu bujori in obrajori.”

“With peonies in her cheeks.” She is our little Lidi Dósa.

“Să te văd!” Nitsa says. Let me see you!

“Bravo!” Bob says, taking pictures. Grinning, Jake starts to take pictures too.

“Frumos!”

“I feel like a circus fenomenul,” Eléonore says, frowning at Jake.

“You have no choice,” Jake says.

“I’m going to look like a clown.” Her voice is barely audible.

“Esti foarte bine!”

As we stumble back out to the car, I almost trip over a rooster, and for a moment I consider swooping it up and bringing it with us. This is the mood — hey my dear hey — the pálinka has put me in. I am also in the mood to hypersubjectively share, thus the thought of adopting animals launches me into a reminiscence about my old dog Clyde — Clyde, short for Claudius, whom my father gave away to the state hospital when I was six.

In the car Eléonore breaks off squares of chocolate to revive us and listens to me ramble on like a moron about how my father had my childhood pet committed, this particular story being a chapter from my most intimate folk oeuvre, a way to signal my gothic origins to new friends. The mad pastor for a father. A childhood under the shadow of the asylum. I can hear something distorted in the way I’m speaking, defective, a little trancy as I talk about Clyde, a good dog turned bad. I never knew why. Maybe Clyde saw something in life that he could not work out, some evil he could not brook, but the sweet, loving dog became uncontrollable, a demon, and, worst of all for my parents’ neighborly peace of mind, a savage exhumer of the dentist’s night gladiolus. One day Clyde was just gone. After that, the only time I ever saw Clyde was at the end of a leash, leading one of the village strigoi on a Thorazinic walk around the block. He no longer seemed to recognize me, and it made me wonder whether he was really in fact my dog, or whether they had done something to remove his memory, or perhaps it was only a convincing copy of Clyde. I imagined a gray trickle above the asylum’s smokestack.

I register my rambling in Jake’s brow in the rearview mirror. He is listening, murmuring uh-huh, mmm-hmm, but something in the mirror makes me think what I often think, which is that when I fell off that train table as a child I never stopped falling. Somewhere, many miles down, I am still falling through the basement floor.

Bob, smoking, ignores my garbled narrative, while working to unwrap one of the meatball sandwiches our hosts from the pensione packed us this morning. The car fills with the smell as Bob gives Jake directions to the village of Dragomireşti. In Dragomireşti, there’s a fiddler by the name of Nicolae Covaci, the brother of Gheorghe. Bob says that Nicolae is “like a Rosetta stone of folk music.”

We are now well up in the hills. My bladder is about to burst from the pálinka, so I’m glad when we arrive at the village. In the street where we park, there are a few urchins kicking a ball that looks like a half-eaten cantaloupe.

We walk down a mazy path between overgrown gardens to get to Nicolae’s yard, where we’re greeted by an old woman who silences the dog and roosters. After a minute, another older woman wanders out and looks around, dazed; then the old man, Nicolae, comes out and sends one of the women to go get his violin, while the other drags chairs into the dirt yard.

Nicolae accepts a cigarette and light from Bob and chats a bit in Romanian with Jake, who clearly regards the old man with great deference. He is toothless and extremely small, wearing a faded plaid shirt, grubby denim pants, and a deeply waled green wool hat — he is so skinny that the twine tied around his waist looks like a piece of rope tied around a log.

His skin is the color and texture of his violin, varnished and chipped.

A small and ancient cat creeps bonily around the rock-strewn yard, wisely keeping its distance from the rooster. There’s an outhouse that looks as if it’s been here for 600 years. It stands off by a copse of spindly trees like a coffin upended, recently exhumed.

Bob asks about another fiddler from this region who is now evidently dead. They talk about Gheorghe, his brother, also dead.

As the old man tunes his violin, the first old woman drones. “Only the old man is left. Only he’s left. He is ninety years old. Ninety years. Now he’s ninety.” Then she points to the other old woman, who has brought out a banged-up guitar, and who takes a seat on a stool by the woodshed with a look of sublime indifference. “She is eighty years old. Eighty. He’s ten years older.”

The old man smokes his cigarette as he and Bob hand off and inspect each other’s violins, then Eléonore films the old man while he and Jake take up, playing some ancient klezmer lament while Bob looks on with an expression of boyish veneration. It is amazing to watch the old man play. To watch his hands. They are thick, his cuticles dirt-black. He wears a chunky watch that somehow doesn’t get in the way as his fingers hunt up and down the worn fingerboard. It is such leaping, slender music. Every once in a while he pauses to grin or let out a rusty, protracted cough.

Bob watches the old man’s bow almost hungrily.

When Bob joins in, he leans into his fiddle, swaying on his bow, and as they get deeper into it, he says to me out the corner of his mouth unimpeded by a Marlboro, “Hora lungă, Bartók shit.”

The old man stops for a minute, takes the guitar from the old woman, tunes it, or does something that looks like tuning, and hands it back.

The woman with the guitar possesses what I can only describe as a truly dumbfounded expression. She sits on the stool with the fatigued air of somebody recently roused from a coma. She wears a mossy shawl around her head and a layer of dull sweaters, in the midst of which I notice a hole directly between where one supposes her breasts to be. It gives me a shiver to contemplate. Beneath her skirts are dusty gray ankle socks and rotten boots.

The guitar is cradled in her lap. Not to mince words, but at the indeterminate, arbitrary moment she takes up strumming the thing, it is horrid. Far more droning and monotonous than the drunken neighbor the night before. She holds the broken neck and bangs away. Just the barest rhythm on three open strings. A chopping thungk thungk thungk thungk thungk thungk. At first it is merely boring, but then it starts to have an untoward effect on my afternoon hangover.

Before I say just how untoward, I should take a moment to properly describe the fully heathen condition of the old woman’s guitar. It really is the beatest, gonest guitar I ever did see. It looks like something that might have been salvaged from the junk wharf on a river, under a bridge, after a flood. The fretboard is nailed on, and the neck itself is wired onto the body with what I imagine is a busted string, which may say something about the priority accorded the placement of said strings. The body is patched with pieces of bile-green plastic, maybe cannibalized from an old jerrican.

Whereas the guitarist at the pensione had two chords, here there are no chord changes. Just an unsteady wham on three witchy strings. She is the cosmic brute steady. The braying, uncooperative mule of time. Another bestial image comes to my mind, of a very dull-witted rabbit. A rabbit that has been cornered, and in its panic hurls and thuds itself against a wall, and if the guitar is the rabbit, the violin is the old man clumsily trying to get a snare around its neck, and, listening, one can only root for the old man to snare it as quickly as possible, or, failing that, for the rabbit to finally break its neck by hurling itself against the wall, you don’t really care which, only that it stop. Needless to say, it does not.

Here is the dark origin of something. Some pagan evil-id thing. Some kind of source, to be sure. Like a sulfur spring. The black gaping mouth-hole of the guitar is chewed open, like the old woman’s maw itself, which, by my careful count, is home to one solitary tooth, though it’s quite sharp.

I cannot take this old woman’s guitar anymore. I bum one of Bob’s cigarettes and excuse myself, muttering that I must go water the horses.

It takes a few moments inside the outhouse for my eyes to adjust, so I can only bumble forth in the dark to unencumber my full bladder without seeing much more than the vague outline of the hole. I can still hear the music, but from in here it’s amusing to think that the thungk thungk thungk and sawing violins are the sound of my friends hewing planks for a coffin, and that I am already inside the box. When I finish pissing I just stand there smoking for a minute, not ready to go back, when I notice that somebody has graffitied in the faintest lettering on the wall, in my handwriting, the words furor poeticus. Have I already been here, without my knowing it?

Then, after I smoke for another minute or so, I turn to the other presence, who, at first, I was trying my best to ignore, because, of course, it’s not real, but my eyes have now adjusted to the half-light of the shitter. He sits there, a slender figure, legs dangling over the hole, with jacket and pants folded neatly beside him, hands propped on the ledge of the stained boards, as if contemplating the subject of jumping. I try to convince myself, at first, that it is just a stain in the wood: an old, man-shaped stain braced as if in the midst of some violent letting go. Whatever it was, no doubt, his presence was an unreliable distortion of my pálinkered mind, my reason doubly compromised by the effects of the evil guitar — of this vision’s absolute unreality there must be no question, but, nonetheless, as the dimensions of his form resolve, it does not make him any less convincing, or less naked. I do recall reading that Bartók was an occasional nudist, so this detail is less startling.

His pupils are the size of pinpricks, as if he’s just pulled away from peeping out a crack or knothole; beside him is a notebook with a few fresh-looking notations. When he notices me he clenches the side of the hole even tighter. Perched on the edge, legs dangling lower in the hole, as if he might be slipping, he seems unbothered by the fumes that waft up from below. I can see that his skin is slightly bluish, like an old mimeograph, and that he’s trembling, because he’s either cold or afraid or sick, I’m unsure. His teeth gleam red in the light, and I wonder if perhaps he has had one of his hemorrhages. Except I know, also from my reading, specifically the article that his son Béla Jr. compiled on his father’s illnesses, that it seemed Transylvania was the only place where he could always depend on his health.

His pupils are the size of pinpricks, as if he’s just pulled away from peeping out a crack or knothole; beside him is a notebook with a few fresh-looking notations. When he notices me he clenches the side of the hole even tighter. Perched on the edge, legs dangling lower in the hole, as if he might be slipping, he seems unbothered by the fumes that waft up from below. I can see that his skin is slightly bluish, like an old mimeograph, and that he’s trembling, because he’s either cold or afraid or sick, I’m unsure. His teeth gleam red in the light, and I wonder if perhaps he has had one of his hemorrhages. Except I know, also from my reading, specifically the article that his son Béla Jr. compiled on his father’s illnesses, that it seemed Transylvania was the only place where he could always depend on his health.

Then again maybe what’s really happened is that he was caught at sunrise, and had to hide out here till sunset.

Then again maybe what’s really happened is that he was caught at sunrise, and had to hide out here till sunset.

Even though I know it is all mad, I listen to the master’s ghost begin to tell me about how, in 1918, after nearly dying in the flu pandemic, he developed an inflammation of his middle ear, and how it sounded like insects scratching and digging at his eardrums. For a time he heard every note on the piano a fourth higher than usual.

This gives me the opportunity to ask about the possible influence of insects on his composition, but he says how that sounds like something Péter would have said, his son who once made the mistake of referring to his father’s music as “atonal,” when Bartók said his music was always tonal, never atonal.

As if reading my mind, he shows me a box. It’s a small cardboard box. It fits easily on his wispy lap.

Inside is a dead beetle the size of a fist.