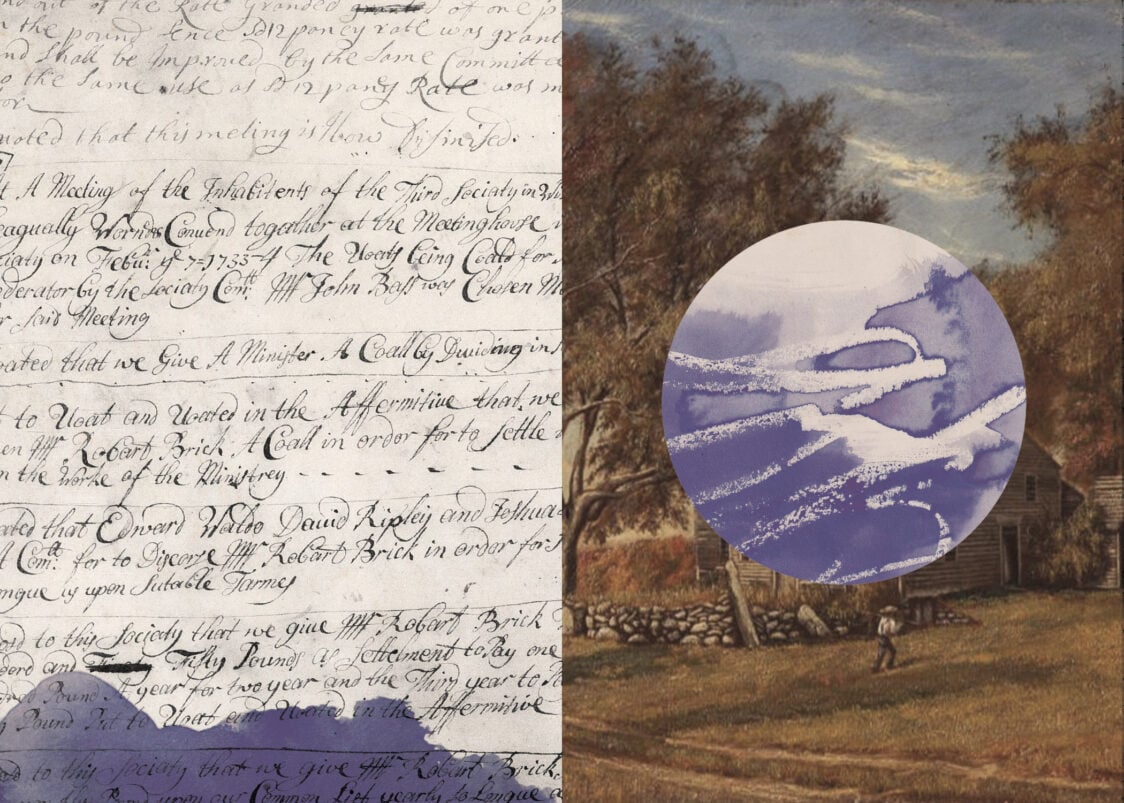

Collages by Vanessa Saba. Source photograph of the northern Brook Road bridge by Gregory Funk, Connecticut Department of Transportation. Courtesy the author. Painting © David Findlay Jr. Fine Art, New York City, USA/Bridgeman Images

Before the flood came the tornado. It touched down out of a purple sky to the west, at around eight o’clock on a humid August morning last year. Barreling east along State Route 14, it veered slightly north at the chain-saw shop and then cut a swath through woods and fields, across Pinch Street, eventually lifting as it crossed Brook Road. It left behind tangles of downed utility poles and electrical wires; sheared trees, flattened corn, and torn-off shingles; dozens of homes without electricity or internet access; and, if you were inclined to feel such things, the vague unease that sets in when nature seems to have a purpose, in this case the intention to assault one town and one town only: Scotland, the home of some 1,500 people in the northeastern corner of Connecticut.

It wasn’t long before the state’s regional emergency management coordinator showed up in a Ford Police Interceptor, along with two other men in a pickup whose door decals announced that it had been purchased with Homeland Security funds. I didn’t know exactly who these men were, why they were here, or what they wanted from me, but since I was the official who ran the town—what we in New England call the first selectman—they had reason to think I would provide what they wanted.

Mostly, it turned out, what they wanted was local knowledge of what lay along the storm’s path and access to those who were affected by it. I directed them to a homeowner whose picnic table, I had heard, had been lifted off the ground and dropped elsewhere, and then to the chain-saw shop, where they told Dana, who was working in the back, that it had been a good thing he’d failed to open the door when he heard what sounded like a freight train outside, because the wind might have blown the roof right off the place. I introduced them to Dana’s boss, Kathleen, whom they asked for any video of the storm that their surveillance cameras may have captured. A day or so later, some of the footage showed up on the news: rain stirring up stones from the driveway, and wind blowing flags—Old Glory and a Stihl banner—straight out from the pole. Then, as if someone were running the video backward, they suddenly reverse direction: the cyclone had passed overhead.

Eventually, the men explained they were looking for evidence that this was no ordinary violent weather event, but a twister, the kind that drops houses on witches. They took pictures and called in drones and looked at the radar and concluded that we had been struck by an EF1 tornado, with top winds around 100 miles per hour. Just another day in Kansas, but rare enough in these parts to bring the TV news vans to town. Yet tornadoes are not as rare as they used to be in New England, and the Homeland Security men would be reporting their results to the National Weather Service, whose models, I reckoned, needed to be tweaked to account for climate change. The meteorologists had gotten pretty good at forecasting the blizzards that hardly ever happened anymore, but not so much these increasingly frequent warm-weather, moisture-saturated, sudden-onset, potentially lethal storms. We’d received no warning that a tornado was on its way, and since such storms were more likely to occur as the warming atmosphere got ever more juiced, this was a problem in need of a remedy.

The next day, I stopped in at Perry Motors, the repair shop that has sat across from the town green for more than seventy-five years. Men gather in the shop’s tiny office each Saturday as they would in a barbershop, if Scotland had such a thing. Russ, its owner, sat behind his gunmetal desk, alongside Bill, a retired federal agent; nonagenarian Don, who had played “Happy Birthday” on the accordion for Russ on the occasion of his eighty-fourth a few months before; Jean, as far as I knew the only other Democrat in the room; and a couple of guys named Ed. One of the Eds had brought his own chair, but the rest made do with what was there—an old trolley bench covered with back issues of auto magazines, along with assorted beat-up chairs and stools. I came in late and ended up standing at the door, from which, like Pheidippides returning from Marathon, I dispensed the news from the front.

They’d seen the Homeland Security truck, and I explained about the prediction models. Several people scoffed, confident that something else was at work here. The Ed who’d brought his own chair knew what it was: the State trumping up the threat of severe weather to force us into electric cars. No one disagreed, not in this group, most of whom were convinced that the government was up to no good, especially when it came to climate change. I told them that it was worse than they thought, that in fact the state had seeded the clouds with silver iodide, that they’d only wanted to make a bad rainstorm but things had gotten out of hand. It took a second for them to figure out that I was kidding.

By then I was tired of exercising restraint. I had announced my intention that spring not to run for a third term in November, so I was coming into the homestretch after four years of running a town that Donald Trump won handily twice, where fuck biden banners flap alongside Gadsden and Confederate flags, where my rights don’t end where your feelings begin is a working slogan as well as a not uncommon bumper sticker. By then I’d failed a couple of times to persuade my neighbors to adopt some modestly progressive climate measures. The town meeting voted overwhelmingly against my proposal to lease municipal land for two solar arrays, which would have added at least $40,000 to our meager annual revenue and earned us a reduced electricity rate. The following year, my proposal to provide for free the first one thousand dollars’ worth of electric-vehicle charging at a station I’d had installed at the library with grant money when no one was looking encountered so much resistance that I withdrew it before it ever came to a vote. People came to meetings armed with notions about exploding solar panels, as well as the specific worry that a rich lawyer’s $100,000 Tesla would somehow set the library (which is made of brick) ablaze while sucking down the taxpayer-funded juice. Underneath these objections ran a river of grievances: about regulators forcing solar power down our throats, about the notion that government money comes from a “grant fairy” rather than taxes, about the unfairness of giving away electricity for free—an inequity that one resident said, at a meeting held during the warmest June in recorded history, could be remedied only by placing a free gas pump next to the EV charger. And even further below it all, the boiling magma of suspicion, and sometimes outright hatred, of government itself, and of the elites who ran it for their own benefit.

Given all that, I was pretty sure there was little point in citing statistics about rainfall and sea levels, or explaining that a little EF1 tornado was nothing compared with what was already happening elsewhere and was sure to happen here in the near future. I figured that if my neighbors hadn’t noticed that it had been a few years since we’d had anything resembling a proper winter; that our trees were being choked by vegetation that didn’t used to stand a chance in these parts; and that Canadian wildfire smoke had fouled our skies for a couple of weeks earlier that summer, then these facts wouldn’t stand a chance. So I played jester to this court, burying my disagreement in a joke. Because the comity—to call it by its correct name, the love—in that office, and by extension, in this little town, did not seem worth sacrificing to even so dire a truth.

This is not to say that Scotland is a stranger to division. It’s been riven from the beginning: 1731, when twenty-six landowners who lived in the southeastern section of Windham petitioned the Connecticut General Assembly to spare them the several-mile walk to the Windham church and give them permission to build their own. This right could be conferred, however, only if the petitioners were granted their own “society,” which, in theocratic eighteenth-century Connecticut, was often tantamount to forming a new town. Almost immediately, a dozen dissenting settlers filed a remonstrance with the assembly. Because the difficulty of turning the stony land into a source of sustenance “renders it highly necessary for us to be at great charge in subduing it without expecting any great profit for some considerable time,” they wrote, they had neither the time nor the money to build a church, hire a minister, and operate a parish. Moreover, they added, the “considerable debate” over the question of ecclesiastical independence, which had by then gone on for four years, left them “much afraid it will promote a great deal of strife and contention among us if your Honors do not interfere and prevent any further proceedings until we are better able.” Despite these pleas, the Honors eventually voted to interfere, creating the Third Society of Windham, soon to be known as Scotland, in May 1732.

Source images: Scotland Congregational Church records, eighteenth century. Courtesy the author. Waldo Homestead in Scotland, Connecticut, 1873 © Connecticut Museum of Culture and History

The fractious run-up to the town’s secession is not noted in church records, nor is any subsequent argument. Every decision—the size and location of the meetinghouse, the arrangement of its pews, its preacher and his salary and the taxes to pay it—was “voted in the affirmative,” or just plain “voted.” Once independence was achieved, everyone with a voice felt the same way about everything, at least on paper.

But absence of evidence is not evidence of its absence, and in fact, there was plenty of strife. Scotland’s first preacher was run out of town within weeks of arriving. The official record notes only that in February 1734, the town voted in the affirmative to call Robert Breck to the pulpit and, the following month, to form a committee to hire a new pastor. But elsewhere we can learn that Breck was accused of preaching that some Bible passages might not be the actual word of God, that right-living Indians might be saved, and that it was possible to earn one’s way into heaven with good works. He went on to espouse similar heresies in Springfield, Massachusetts, where his ordination was vehemently opposed by a colleague up the river in Northampton named Jonathan Edwards. The clash between the two, which came to a head at an inquest that included testimony from scandalized Scotlanders, was one of the early skirmishes of the Great Awakening. The attempt to use legal means to remove Breck from Springfield eventually resulted in some of the colonies’ first legislation separating church from state.

Scotland’s scribes could not have known they were in on the earliest stirrings of such history, but they surely knew these were profound and vexing questions. After five years of polarizing argument about separating from Windham, they may well have just wanted to move on. They had a wilderness to subdue, after all, and a city on a hill to build. Ongoing clashes over fundamental matters could only slow them down and—insofar as they might grow from or feed blasphemy—risk the plunge into the fiery pit.

The virtue of reticence is enshrined in the earliest documents of the New World’s Puritans, including the 1636 covenant fashioned by the settlers of Dedham, Massachusetts, who promised “to profess and practice one truth according to that most perfect rule, the foundation whereof is everlasting love,” and to meet together en masse to determine how best to build on that foundation. The fabled New England town meeting that grew out of such an arrangement still governs many towns, including Scotland, but it would be a mistake to think of it as the pure democracy it might seem, at least in its origins. As the historian Kenneth Lockridge points out, the Dedham Covenant did not call for “a clockwork balance of one power against another, but voluntary restraint on the part of all concerned.” The point of meeting to discuss affairs of church and town was not to determine what the majority wanted, but to forge a consensus to which all would subscribe, leaving those who disagreed to surrender their agency in order to strengthen the everlasting love available only to a community of believers. Without that restraint, the settlers understood, a town or a church could easily devolve into one that is permanently and disastrously polarized.

Lockridge calls this approach “conservative corporate voluntarism,” and if those first two words do not endear it to modern ears, still it would be a mistake to dismiss it out of hand. After all, a society that can’t put aside differences in the midst of a pandemic (or, for that matter, in the aftermath of a tornado), that can observe its own fracturing and still be helpless to repair it, is a society in deep trouble. If emergency cannot bring us together, then we are surely lost.

Just shy of four weeks after the tornado, at 12:59 pm on Wednesday, September 13, I got an email from Gregory, an engineer at the Connecticut Department of Transportation (DOT). Its subject line:

“BridgeWatch—NEXRAD Alert.” Citing a notice from the National Weather Service warning that the rain that had been falling all day was about to start dumping at a rate of a couple of inches per hour—enough to qualify it as a “25 year event,” though it would turn out to be a fifty-year one—he recommended that “the Town direct personnel to check for scour related damage” to its bridges and close those that seemed in imminent danger of collapse.

Scotland’s bridges, many of which were built in the Thirties, were designed for a different climate—one in which less rain fell, and in which twenty-five-year storms were unlikely to happen more than once every twenty-five years. More rainfall meant more water in Scotland’s streams, especially Merrick Brook, a waterway that runs from north to south through the town. Along the way, it flows under eight bridges, four of which, in 2014, were deemed to be “scour-critical” by state DOT engineers, meaning that their foundations are at risk of collapse. When swollen by rain or snowmelt, Merrick Brook runs behind and beneath the abutments of Scotland’s bridges, scouring out the ground that supports them until they can no longer hold up the deck. In one case—that of the Bass Road bridge—so much material had been washed away that the state recommended that it be closed. Soon after, we laid a prefab steel bridge on top of the compromised bridge, anchoring it to abutments in the roadway. It was not a permanent fix—even the new structure was still perilously close to the ever-expanding brook, and it was just one lane wide—but it cost only around $105,000, about 5 percent of what we might pay for a new bridge, and it worked.

We knew that it was only a matter of time before all the bridges went the way of Bass Road’s, but the costs of measures to improve their resilience, let alone the costs of replacing them, were way beyond our means; Scotland has virtually no commercial property to tax, and by that measure it is one of the least wealthy districts in the state, its revenue mostly coming from its 625 or so households’ property taxes.

The only means we had to carry out the inspection Gregory had recommended was for me and Bill, the town’s road foreman, to get in our trucks, drive around in the pelting rain, and look with our own eyes. By three o’clock, what we were seeing was not reassuring: logs floating down Brooklyn Turnpike as if on their way to a mill; catch basins vomiting into the gutter; gravel driveways sliding into the road; and, as I drove onto one of the two bridges on Brook Road, water beginning to spill onto the deck. Merrick Brook, which usually gurgles peacefully seven or eight feet below, had entirely escaped its confines, transforming into a furious brown monster that beat against the underside of the bridge and threatened to swallow it whole. From upstream a log approached, bobbing like a struggling swimmer. The bridge groaned and shivered as the log ducked under it, scraped against its underside, and shot out the other end. By the time I got back to my truck, the water level had risen to my ankles.

By around six o’clock, the other bridge on Brook Road, right next to the grade school, was also underwater, as was the bridge on Route 14. I stopped at its eastern edge, where the fire department was trying to prevent traffic from crossing. Just downstream, a pond was spilling over its banks, the water approaching an old millhouse. Its residents, a young couple and their baby, were running to their car, the father stopping to help me pull yellow tape across the roadway. From there I hurried to the firehouse, where I had to run a Board of Selectmen meeting. Before I arrived at the conference room, a volunteer told me that the first Brook Road bridge, the one I had inspected only a few hours earlier, had just given way, dropping out from under a fire department truck as it crossed the bridge. The front axle had made it to solid pavement, but the rear wheels were now dangling uselessly a foot or so above the fallen deck. I brought the board meeting to a quick end and drove to the scene. When I got there, the firemen were unloading equipment to prevent the truck from spilling its contents in the event that the roadway crumbled underneath it. At about ten o’clock that night, the bridge finally fell into the brook, but the truck did not follow, and was hauled to safety by a wrecker.

By eleven, Bill and I had closed off access to the fallen bridge with loads of dirt dumped into the middle of the road—a cash-strapped town’s way of preventing people from driving into a void they would not see until it was too late. By midnight I was finally heading home. On the way, I stopped at the Bass Road bridge, steadying myself against a post as I shined my flashlight on its underside. As soon as I put weight on it, the post tipped over and splashed into the brook, nearly taking me with it. What I saw sickened me: the brook had wiped out its banks, leaving the new foundation exposed and the bridge teetering. By one in the morning, John, the emergency management director, and I had barricaded that bridge with piles of dirt, and by one-thirty I was in bed, counting the days remaining in my term like sheep, and cursing the gods of deluge for wreaking havoc now rather than sixty-nine days from now, when figuring out what to do about two wrecked bridges would have been someone else’s problem.

And it wasn’t only two bridges. It was three. Morning brought a call from Brenda, the chair of the town library board, who reported, as calmly as she could, that she could see Merrick Brook through a pothole that had opened up on Brook Road, just north of the bridge by the school. A little later, a DOT engineer told me that divers had determined that the stream’s swell had washed out the soil holding up the road as it approached the bridge. The pothole Brenda had seen was on its way to becoming a crevasse. There was a risk, the engineer said, that the fissure would expand, meaning that the bridge was unsafe to cross at any speed, even on foot.

Brenda was right to be alarmed, not only about the safety of drivers and pedestrians, but also about the six homes located in the half mile between the two bridges, including hers, that were about to be cut off from the rest of the world. She said she wasn’t sure her neighbors knew of the imminent peril. My administrative assistant dug up their phone numbers and called to tell them they should, if possible, vacate their homes by three o’clock, a deadline I made up on the spot. She managed to reach all but one of them. One of the households, she reported, included a newborn, and another a boy with a feeding tube that, his mother later told me, he sometimes yanked out, after which they had about a half hour to get him to a hospital before the stoma closed.

A bridge down in the brook with another on its way, six stranded families with groceries to buy, jobs and schools to get to, and homes that could no longer be reached by fire engines or ambulances, with more rain to come: if it wasn’t an emergency yet, it would be soon.

There is no book on how to be Scotland’s first selectman. But Nelson Perry, who did the job for thirty-two years until his retirement in 1995, did leave behind a list, typed on onionskin, detailing thirty duties: maintaining highways, issuing pistol permits, and supervising town cemeteries, among other things. The town’s penury forces one person to assume all these responsibilities, few of which I knew anything about before taking office. On the other hand, I had lived a DIY life, fixed my own cars, and built my own house, and I knew how to drive a truck and run a backhoe. I also knew how to look things up. But there is no YouTube video telling you what to do about two kaput bridges and six trapped families, let alone how to do whatever needs doing when you don’t have millions of dollars and years in which to do it.

Fortunately for me, and for the town, the rain carried with it some kind of unguent or pixie dust, something that smoothed out our rough Yankee edges. After Brenda called to worry about her neighbors, Tom offered use of a cow path that ran through his fields, west from Brook Road to Pinch Street, and from there to civilization, and agreed to delay a project that would have fenced it off. Danny showed up with a hay wagon attached to his tractor to take the stranded people and whatever stuff they grabbed up the cow path to Pinch Street. His brother Joe offered one of his company’s school buses to bring them to the firehouse, where they could reunite with family members who had gone off to work or school before the last bridge failed. The volunteer firefighters drew up an emergency action plan (involving staging areas, communication protocols, and utility vehicles, some carrying stretchers and medical supplies, others pumps and hoses) that they shared on a hastily arranged Zoom call with nearby fire departments. One of the people living on what came to be known as the Island offered the firefighters a disused swimming hole behind her house as a water source to replace the now unreachable standpipes, and used her little garden tractor to clear a trail to it.

Soon enough, the islanders had no need to evacuate. Some used bicycles and carts to haul their groceries. They parked at the school and walked home; or, if the cow path wasn’t too muddy, they arranged with Tom to use it for their commutes. The school superintendent supplied the parents, including one with whom she had been bitterly beefing, with home-schooling materials, and offered to escort any kids who had walked as far as the bridge the rest of the way to school.

For days my phone was hot to the touch; people were calling constantly to ask how they could help. Another Tom, this one a log-truck driver, thought we should fill in the crater at the bridge next to the school with concrete to strengthen the crippled abutment. His brother Jim offered use of one of his log trucks to move the concrete blocks we might need as a foundation for a makeshift crossing. Chris, trained as a civil engineer, thought we could construct a bridge out of shipping containers. One citizen sent me a picture of a similar arrangement using a half-submerged city bus. Another called to tell me about the availability of engineered wood beams long enough to clear the span and serve as a foundation for a makeshift crossing. Yet another roads-and-bridges guy offered expert advice on some of these suggestions. Even the Scotland Residents page on Facebook, usually seething with vitriol directed toward neighbors and local officials alike, was full of solicitude and suggestions and offers of help.

Most of the time, I could not take people up on their suggestions, and when I told them so (after thanking them), they sounded more disappointed than relieved, as if some elemental desire—to help, to be of service, to gain the ecstasy of community—had stirred within them and then been denied its satisfactions.

The only complaint in the first days came from Holly, the mother of the newborn on the Island. She had been crossing the bridge by the school with her infant in a stroller and her husband and other child behind. When a DOT engineer and I reminded her that it was unsafe for pedestrians (a warning that was being roundly ignored by the Islanders), she snapped at us, saying she had no choice. The family continued on. Politician that I was, I caught up to them, smiled, asked her name, and told her mine. Putting a face to it, she was mortified. She thanked me for working so hard and apologized for being unpleasant. I wished her a good day and later, on Facebook, she apologized again.

If the supply of altruism outpaced the demand, it did not cheapen the sentiment. But in other ways, the laws of capitalism prevailed, as usual. A young man named Derek, a project manager for an out-of-town construction company, attached himself to me in the days after the flood like a hungry puppy. He had ideas too, some of them even more harebrained than those volunteered by Scotlanders. But at least one seemed viable: to move the now useless Bass Road bridge to one of the Brook Road locations and drop it onto wooden platforms. He’d already figured an estimate for the job: $55,000. In the end, the bridge turned out to be too short for either of the Brook Road locations, but Derek had another proposal: he had a contact at a crane company that owned a jumper bridge, a steel gangway that was just long enough to replace one of the collapsed bridges. I think he wanted me to let him arrange the deal, but I coaxed the company’s name out of him, along with the name and number for its regional salesman, and by noon on the Monday after the flood, the jumper bridge was on the scene, along with a crane and a crew of riggers. The ramp, it turned out, consisted of two six-foot-wide steel decks without guardrails, lights, or markings. The cost of the effort was breathtaking: around $13,000 for the crane and crew, and $3,500 for each day we used it—and that was after the salesman, taking pity, gave us a discount of $1,000 a day.

Disasters are lucrative business opportunities, and not only for a crane company that happens to own a temporary bridge. Some companies stock products specifically for the emergency market. The New Jersey–based Acrow Corporation, for instance, offers a bridge that comes in ten-foot sections designed to be put together with nuts and bolts and pins, like an Erector Set, in a matter of a week or so. For $271,800, we could buy enough sections to span the brook near the school, and for another couple hundred thousand, a contractor would build the foundation and assemble the bridge. In the month it would take to do that, renting the jumper bridge would add up to at least $105,000. Ancillary costs—for concrete blocks to support the jumper bridge, equipment rental, and casual labor supplementing foreman Bill’s—might approach $100,000. Throw in another $25,000 just because, and you’re at nearly seven hundred thousand dollars—depleting all the funds we had in reserve, and well over 10 percent of our budget expenditures for the year. Ultimately, the disaster was financial as well as infrastructural, its victims the very souls whose wish to help had been kindled by the flood: the taxpayers.

The Puritans might have wondered what sins the residents of Scotland had committed, such that the stranded homes were on the very same stretch of Brook Road that had seen some of the worst damage from the tornado. And they would have taken it as yet more proof for their every-man-for-himself-and-God-against-all philosophy, and therefore a clear indication of how important it was to make and uphold their covenants to care for one another. Their God might not have been moved to mercy by their good works, but by binding themselves into a town, the Puritans could extend compassion and aid (and reminders about that angry God) to one another, and make this life a little less difficult, if not quite joyful.

Perhaps this is why their villages huddle around town greens like Conestoga wagons circled up for the night: to create a feeling of safety in a hostile world. The town meeting surely creates a sacred inside and a profane outside, but gathering to decide upon every detail of civic life is a distraction from plowing fields and erecting homes and all the other work of building a civilization. So by the mid-seventeenth century, many New Englanders had decided to select a few men to attend to the daily business of the town. The town meeting still assembled, but less frequently, to determine major items like the annual budget. Otherwise, the general welfare of the town and its people had been turned over to the selectmen—that is, to a government.

It was a government employee, a DOT engineer, who, on the day after the flood and before Derek ever told me about the jumper bridge, suggested a way to reconnect the Island to the world more or less immediately—and at no additional expense to taxpayers. In his off-duty hours, he served in the Connecticut National Guard, and he explained that the Guard had a bridge that could be assembled in a matter of hours, that it was stored at a base a mere forty-five minutes away, and that his crew would love an opportunity to deploy it in a real-life situation. He called it a dry support bridge. The next morning, I joined a Zoom call arranged to field my request for the Guard to bring the bridge to Scotland.

Major Seth, the National Guard officer on the call, assured me that the Guard’s hearts went out to us, then listed the obstacles to fulfilling our request. Local emergencies weren’t generally within the scope of the Guard’s operations. Civilian vehicles couldn’t traverse the ramps up to the bridge, and it had no guardrails. We’d need 24/7 traffic control. We would have to certify that there were no commercial alternatives available. But mostly thanks to the DOT guy, I was ready with rebuttals. I had drawings of the bridge showing that private vehicles could make it onto the bridge. I cited Connecticut’s State Response Framework for emergencies, whose Section 3.1.2.29 lists “Dry Span Bridging” as within the scope of Guard operations. As for a commercial vendor, I had not yet called the crane company, so I could report, not untruthfully, that I had not been able to locate one. Major Seth seemed unmoved, but he didn’t say no outright, and the call ended with vague promises to consider the request.

That afternoon, the DOT engineer told me he’d been ordered to stop talking to me. But another order had already gone out: for Major Seth to carry out an “engineer assessment” on Saturday, at 0800 hours. He seemed unhappy when he called to confirm his assignment, complaining about the early hour and asking if he could come at 0900 instead. He also asked me to keep his visit quiet—he didn’t want people to get the idea that help was on the way. That’s why he and his crew arrived in civilian vehicles, he later told me (he didn’t mention whether that was also the reason he showed up in camouflage).

“I’m from the government, and I’m here to help,” he said to me, stretching out his hand. He looked too young to remember Ronald Reagan, but I was pretty sure he understood irony. At a big round table in the firehouse meeting room, he rehearsed all the reasons his mission couldn’t be accomplished, and I reiterated my counterarguments. We traveled to the site in a convoy: the major, three of his soldiers, John, and me. I led the way, careful to take the route with the widest roads to assure him that our rural byways, contrary to his worry, could accommodate the large vehicles carrying the bridge. I hadn’t thought about the overhanging branches, however, which, he said, were sure to ding the apparatus as it passed underneath. He reminded me, not for the first time, that the bridge was a federal asset, entrusted to the care of the Connecticut National Guard. He didn’t want to piss off the Pentagon.

Major Seth’s crew poked around the wreckage, taking measurements and notes for forty-five minutes or so while he and I made small talk. Once they were finished, he assured me he’d have an answer by the next morning. The crew packed up and drove off, stopping briefly to take photos of the threatening trees.

When I hadn’t heard from him by one-thirty on Sunday, I sent a text to the governor, a couple of state senators, and anyone else who had been foolish enough to provide me with their number: “Radio silence from CTNG re emergency Bridge. More rain forecast. If they can’t/won’t, then I need to know so we can improvise something.” Shortly thereafter, Major Seth called to tell me that the analysis was still under way and would not be complete until the next day. But even if it was a yes, he added, the town would still be on the hook for charges. I asked how much. He told me it would be something like $450,000, part of which would pay for the sentry who would be posted there around the clock to keep civilians away. So the Guard wasn’t going to say no, they were just going to charge us exorbitantly for a bridge we could not use. It was, as they surely knew, an offer I had to refuse, which I did, in short order, right before I called the guy with the jumper bridge.

But the Puritan idea of government was not completely dead. In fact, it was alive in the most unlikely of places: the Department of Transportation, whose engineers—among them Rob and Andy and Gregory and Mikhail and James—had arrived early the day after the flood and stayed on the scene for days. Some of them had stood in the driving rain on Monday, and when the jumper bridge looked too precarious for their liking, diagrammed in the mud their ideas for shoring up its support. They’d called the division chief of bridges, who called me that evening to go over an idea they’d hatched together to pick up the bridge, flatten the bank, and add some gravel, to make a pad; build a wall on that pad using concrete “Mafia blocks”; and lay the bridge back down. Rob and Andy returned on Tuesday and oversaw the operation—directing the crane and backhoe, measuring and confabbing and measuring some more, climbing down into the ditch to shovel and scrape with their own hands, asking for an inch more dirt and then another inch, and calling for the blocks to go just so—until they were satisfied that the bridge could hold cars and school buses and tanker trucks and fire engines, and told me that it was safe to notify the public that the Island was an island no more.

The engineers weren’t the only denizens of the deep state who came to our aid: There was also the DOT commissioner who pushed Scotland to the head of the line to replace the washed-out bridges, with 100 percent of the cost covered by the state and federal governments, and who effectively ordered his engineers to drop what they were doing and design the supports for the Acrow bridge that would serve in the meantime. The state legislators who Virgiled me through the circles of influence and favor to connect me with the people who could intervene on the town’s behalf. And the governor himself, who called late on a Friday afternoon, a Democrat who responded reliably to my texts, and whose appearance at a nearly inaccessible rural road in a firmly Republican town on a dark and rainy Monday afternoon was not exactly of great political benefit to himself. They didn’t say it, but if they had it would have been without irony: they were from the government, and they were here to help.

I have no idea what the original Scotlanders would have made of this outpouring of aid and comfort from community and government alike. I like to think they would have recognized in our flood and its aftermath a modern version of the Puritan dream: a community bound by love, a government that embodied it, and mutual protection from God’s wrath expressed as altruism. I also don’t know what they would have made of what I said to the TV reporter who asked me how we would pay for the emergency bridge: “So what is the plan moving forward?” I didn’t remember my answer until I looked up the clip later. We’re standing in front of a crane on a dark, wet afternoon. Underneath my soaked baseball cap, my eyes are dark and bleary, my face stubbled and worn. “The plan moving forward,” I say without hesitation, “is to get on my knees and beg.” I suspect my Puritan forebears—for though I may be a lapsed Jew, if you participate in the civic life of a New England town for forty years, and run it for four, I promise you will count them among your ancestors—would have nodded at the image of me in supplication and said: “Of course. What else?”

For a moment, we had what they had: a communal purpose that draws us together—in their case, an angry God, in ours, angry weather—and leads us to put aside differences, or at least to surrender them to exigency. And in that same moment, I had something I hadn’t for the four years I’d led Scotland: a reservoir of goodwill on which to draw as I expressed views I’d mostly kept in check all along. I wrote it in my head, rehearsed it in my car: a sermon on the meaning of recent events, on floods and tornadoes as evidence of our sins. Not sins against a God holding us over the fiery pit, but against an earth that was becoming one. I’d preach about the sweltering summer just past, about the spirit that had moved neighbors to help neighbors, about the need to draw on it to save ourselves from calamity, about the necessity illustrated by the tornado and the flood. We must face the truth, I’d say, no matter how difficult, and we must face it together, for it belongs to everyone. And maybe, just maybe, we should revisit the solar farm and the free EV charging.

I didn’t just have the support, I thought, but also the opportunity: a town meeting, at which almost a hundred people gathered to vote on whether to take nearly every last penny we’d managed to save over the years and allocate it to providing a safe and reliable way for those six stranded families to live their lives. No one talked about grant fairies or Democrat tax-and-spenders or corruption and malfeasance. No one blamed anyone—not a single person even spoke against the question—and when the time came to vote, there was only one nay. People lingered after the meeting, as if to extend the joy of restraining themselves in service of one another (for we all knew who would pay for this in the end) for just a few more minutes.

The sermon I prepared was a good one, worthy of Jonathan Edwards, I promise. But I never delivered it. As for my reasons why, the wish not to endanger the nearly universal goodwill (not to mention adulation) that people had been showing me for a couple of weeks—in short, cowardice—would be near the top. But not too far down would be the recognition that nothing could threaten our unity like the truth: that even though this was exactly the time to point out the danger we’re in and its immediacy, it was, for the same reason, exactly not the time. We need one another too much to risk that fight.

There’s one thing the Puritan preachers had that I did not: a congregation held together by their conviction that they all faced the same predicament and so they’d better do it together. But even as they preached in New England, back in Europe, Enlightenment philosophers were turning their notion of religious freedom into a much more comprehensive liberation, one that would eventually kill off their wrathful God. I don’t mean that as a lament. There is a fine line between restraint and repression, between persuasion and oppression. But the recognition that community is the correct response to the extended emergency we call life, that this must come before everything else, that we are all we have, and that we forget this at our peril: this is one thing the Puritans got right, and that we have lost in the floods of time.