Chatham County, North Carolina, population 63,505, is in the geographic center of the state. We are 710 square miles, eighty-nine people per square mile. An improvised web of old roads has settled across the county, most of them named for a long-gone church that once sat at the road’s end, or for the family that once owned the land they now transect, or the store that once stood at the crossroads. Even the names of those places still standing can confuse an outsider. For example, on Saturdays you can drive down Reno Sharpe Store Road to go play your guitar at what’s known as Reno Sharpe’s Store, though it’s no longer a store, and Reno died a few years ago. You would only know this if you’d lived here awhile.

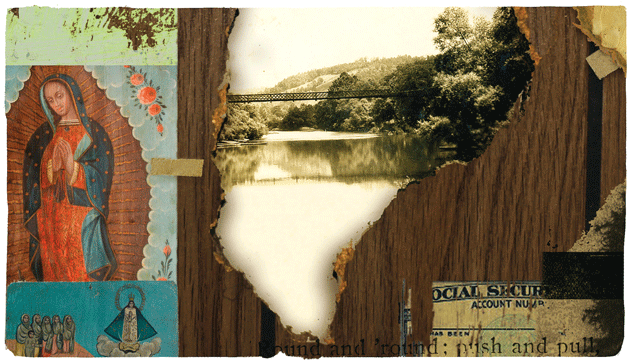

Out on Lorax Lane they manufacture and sell biodiesel, which explains the incongruous number of old Mercedes sedans clanking around. Many of the fields formerly planted with cotton now grow organic vegetables for the local market, or they’re filled with chicken barns and cell towers. Day by day the rest go back to pine forest. In the towns, the detritus of the storefronts’ many transformations — the drywall, the nails, the broken bits of concrete, the old newspapers — is everywhere crunching underfoot. The patron saint of our Catholic parish is St. Julia, a martyred Carthaginian slave.

At one end of the county, in the middle of the woods, there’s a small, lifeless circle of dirt twenty feet in diameter, called the Devil’s Tramping Ground going on 150 years, where Satan himself is said to pace at night. The whole county is a series of linked folktales: of a race of famously plentiful rabbits now nearly disappeared, of deadly freshwater mermaids found where the Haw and Deep Rivers meet to form the Cape Fear River, of the dribbling fonts of miraculous spring water named Faith and Love, and of the ghost dogs in the abandoned shafts of Ore Hill overlooking the springs below. Out on Russell Chapel Church Road, just past Elf Way, a woman has erected a sign in front of her trailer, its message written in foot-high black letters: get to no me befor you judge me.

Three unnavigable rivers split the county. They must have been mighty and cataractal when they cut down from the mountains some geologic ages ago, but the mountains are hills now, and the rivers are flat and full of old rock. The county now sits at 200 to 770 feet above sea level. This is the Piedmont, a waypoint for the traveler, the space between long-ago tide lines. It’s profoundly green in the summer, but not bright green. A washed-out green. Europeans arrived here in the 1740s, most of them Quakers and Poor Palatines. At that time the area was frontier, the hinterland, a virgin territory that could be conquered and civilized. The settlers were subsistence farmers and craftsmen, usually both at the same time. In Chatham County they became hard-core homesteaders.

The mountains were scoured, sifted, and carried off by erosion, exposing rich veins of clay that could be mined, collected, purified, turned, and fired. This region is famous for its pottery, mostly stoneware. Depending on the clay and the ingredients in the salt glazes, our pots become a deep gray, or the color of warm sand, or a veiny light green the color of a camellia leaf’s underside. Potters used to test clay out in the field by spitting on it, rolling it out like a worm, twirling it around a finger to see if it was plastic enough, biting it to see if there was any grit.

This clay has long contained the tombs of Alstons, Matthewses, Wrens, storekeepers and farriers, postmen, minders of the gins and mills. Soon we’ll be adding new names: Cuadros, Vincente, Santiago, Álvarez, Mejía, Estrada, the claim jumpers and infiltrators, the new colonizers, the squatters. They have rushed into this place: Hispanics now constitute 13 percent of the county’s population (8,228 of 63,505), up from 1.4 percent (564 of 38,979) in 1990. Most of them have come here for work in meatpacking, landscaping, and construction. The white population has grown steadily, but the black population is down to 13 percent, from 23 percent, in the same twenty-year period. A usurpation has taken place, a transfer among the powerless — a trend repeated throughout the old states of the Confederacy.

Esteban Almanza* came here a decade ago to be a chicken wrangler. In the mornings he walked into the barns atop years of hardpack chicken shit, among mobs of stuporous birds, to snatch them up six at a time and stuff them into cages stacked five high on a flatbed that, just before dawn, would whine and rattle through the towns and down the lanes until it hit the highway and pushed on toward the slaughterhouses just then beginning to throw off morning steam. The trucks sometimes overturned on the twisting back roads, and when this happened the wranglers came through to catch the survivors. Sometimes a chicken held out and was never caught, and for a time it would wander the woods, a strange, white, top-heavy creature.

Father Pedro and I drove to the Almanzas’ trailer in a battered Honda shared by the three brothers of his friary. The trailer sat at the joint of two gravel streets overhung by viny oaks on a halo of dark and shiny compacted dirt. When it rained it appeared the trailer had broken its mooring to float on a bright orange lake. The trailer is a cousin to the old tenant shack, but unlike the shack, it has vestigial wheels tucked up under itself and could be moved if necessary.

After setting the parking brake, Father Pedro leaped from dry patch to dry patch, ordering me to stay away from the mud because my wife, he believed, would kill him if he sent me home soiled. “Hola!” he shouted through the trailer’s doorway — which, it being too hot for doors, was covered only by a lacy drape to bar flying insects. As I ducked through the drape, I smelled bleach, pine cleaner, and frying oil.

Esteban wore a white shirt and pressed jeans, his thick, dark hair combed back. He was fine-looking, with sharp cheekbones, a pointed chin, and a high forehead. An animated speaker, he stuttered, which Father Pedro tried to cover up in his interpreting. Esteban looked at the ceiling when he was thinking about what to say.

María, his wife, worked in the processing plant and, to supplement their income, baked bread. The bread of María Almanza was small, round, flaky, built atop a thin layer of something pink and sweet, dusted with sugar, gathered in old plastic bags and once a week hauled through the trailer park in a red wagon. María was quiet, thick-bodied, and bright-eyed. She wore a green cardigan and her long hair was drawn back tight from her face, which was wide and dimpled. María listened and watched me as her husband talked. Esteban moved like an acrobat. María could move quickly through the trailer without seeming to move at all.

The Almanzas lived in a chaos of maximized space — colorful mosaics of paper napkins, plastic utensils, plates, spices, toothpicks, sugar, pencils and pens and erasers, bottle caps and crayons, everything stacked neatly. At the stove María pushed up the sleeves of her cardigan and pulled out the bread. The sound of the one window air conditioner sometimes interrupted the silence during the lulls in our conversation. The Almanzas ran it only when Father Pedro came to visit or when María was baking.

That first day we sat in the kitchen on patio furniture donated by the church. Esteban and I passed serrano chilies back and forth, which María had lightly fried with her daughter Sara balanced on her hip. We talked about things in the way people talk when there’s a priest in the room. You never saw such a pious and happy group. Esteban spoke at length of his love for the church, and María about her great job cutting chickens on the line.

Esteban waved his hand at the bread. “Sit down, eat. Eat more.” He told me that when they came to North Carolina there was no bread like at home, and so they saw there was money to be made. He didn’t tell María to sell her bread, he said; she does this for herself, just like the other women in her family. “We have six children!” María turned the air-conditioning up a little, and for no particular reason we all looked out the window. On hot days in this territory, the rippling and heated air from the chicken barns gets lifted up and out by enormous fans, sometimes making the barns shimmer like mirages.

Esteban led me outside while Father Pedro stayed in the trailer eating corn tortillas. The cicadas whirred, starting out for the evening following thirteen years of sleep. Esteban poked at his car, a blue Chrysler sedan with an unpainted front left fender. He fiddled with the distributor cap and the solenoid but nothing got fixed, and after a while he gave up and leaned against the car. He gave a deep, satisfied sigh and crossed his arms. The sun had gone bright red just before disappearing behind the trees. The children of the neighborhood had quit the street. At a certain angle between the raised hood of the car and the corner of the trailer, it was impossible to see any other hooch or shack, or to hear the sound of any other human. Even the six Almanza children had gone quiet. It became dark. The streetlights don’t work, Esteban said. Actually, he pointed at the dead lamps and said: “No light.” Soon all I could see of Esteban was his white T-shirt.

Back in the trailer I took a quick photograph as I got ready to leave. In the background, the eldest girl, Paula, a very shy young lady, sat on a twin bed that doubled as a couch. She looked everywhere but at the camera — out the window, down at the carpet. María wrestled with her baby; the littlest brother, Daniel, scratched his armpit; Gabriel looked out of the frame at the other middle brother, Rafael. The photograph only hints at the presence of the eldest son, Arturo, off to the left, who I remember was cocking his head and squinting hard at me. Arturo then went out back, where he could be seen through one of the scratched and clouded windows beating an old metal patio chair with a piece of fence post. The chair vibrated, wang-wang-wang, and he scowled. “That one will be a priest,” said Esteban.

One day Father Pedro and I were drinking orangeade at the Almanzas’ when María returned from selling bread. The children scattered into the trailer park to find their friends. Just a few bags remained. María carried them heaped in her arms and put them down on the table.

Esteban kept eight mason jars of barbecue sauce of varying colors and consistencies on the shallow windowsill above the kitchen sink. These were his attempts to re-create the sauce he’d discovered washing dishes at a local barbecue joint. He thought I would be particularly interested in this, as it had been his observation that “Southern is barbecue.” He put the sauce on carnitas and beans. Southern style. He told me this was serious work, work that would be remembered someday by his children when they had their own sauces and their own places to make them.

María seemed less sure than Esteban of the essential benevolence of the universe, or of a country that would let Esteban go on making his sauces till his children were grown. I think she had a better understanding of the world’s dark traps and sudden reversals. Whatever happened was hardly ever a surprise to her.

María had been called Esperanza for years, which was the fake name in her employment file and on her identification card at the chicken plant. Esperanza had an exciting life. Esperanza was the one who had friends in the break room and on the line, where they stood shoulder to shoulder keeping one another warm.

She was expert in lots of things, including the removal of ribs from a chicken. Every day the chickens passed by her station, one every six to twelve seconds, impaled on stainless-steel cones, breasts facing the knives. Cut and twist, dump the ribs. María and the others wore hairnets and smocks. Their breath mingled as cold mist above them. She knew it was a terrible job, but she also made clear to me that she felt important doing it. She’d never seen so many machines in her life, she said. Some days the most efficient deboning line won a free lunch brought in from the Chinese place down the street, and she looked forward to that.

(At home there is no ceremony in María’s baking, never a dramatic display of her wares. She rolls up her sleeves, goes to the oven, and pulls the breads out, dumping them in a pile in front of Esteban. Esteban burns his fingers a little when he transfers them to the bags. When María needs a child to take a bag of bread out to load into the little wagon, she looks up at the ceiling and calls out. It’s only a minute before one of the children reports for duty. María presses food on me every time I see her. “Hola, here’s food,” shoving it into the pockets of my coat. Sometimes it’s just day-old tortillas, but they’re wrapped twice in tinfoil carefully crimped at the edges.

“This is how they made it back in Ostutla,” María says.

“Maybe someday we’ll go back there,” Esteban says. “Or maybe not. God’s will.”)

After showing me the barbecue sauces, Esteban sat at his normal spot at the circular table, feet up on the temporary storage shelves that served as their pantry and a drying rack for clothes. When he passed María he stroked the back of her neck with the tips of his fingers. In that place and at that moment — with a priest and all their children present, with every lilting word asserting the pieties of churchgoing and nose-down industriousness for themselves and their posterity — this frank and open tenderness surprised me. Much became clear then, especially the mystery of how they’d made that broken-down, tin-can trailer seem so large.

I told María she should sell her bread downtown, in Siler City. I decided this was good, sound business advice, thinking especially of the three or four blocks of old commercial buildings that would be nearly empty if not for the tiendas and nail salons and the Farmer’s Alliance, with its homemade honey, hoop cheese, and affordable dungarees. I thought maybe if she sold more bread and made more money that way, she wouldn’t have to risk being Esperanza.

She said: “I’m afraid.” Afraid? “Yes, I stay close to here.”

I asked whether she was afraid of the crowd of old men appearing at the storefront where they handed out canned goods once a week.

“No, no,” she said. “I know them.” Then what? “I don’t know.” There must be something. “It’s nothing.”

But it wasn’t nothing. When I got home I received a phone call from Arturo. “Why are you doing this?” He said he was asking on behalf of his mother, but I didn’t believe him.

“It’s just what I do,” I said. I heard fear in his voice too, and I wanted to reassure him, but I didn’t know, really, if there was anything I could say.

For months I returned to the Almanzas’ trailer again and again. Sometimes, early in the morning, the chicken plant clanked and hissed, and the smell came through the cracks of the battened windows. There are rooms like this on old ships, paneled boxes with small windows and exposed plumbing, nature raging at the porthole.

“I had the devil in me,” Esteban told me during one visit. He’d been a bad sinner before getting saved, he wanted me to know. This revelation made Paula embarrassed, though she was pretending not to listen. She blushed and sat against the wall under an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“He says he had the devil in him,” Father Pedro said, in case I hadn’t caught it. “But I tell him the devil is in all of us.”

Esteban tells me about how he fought off the devil of drugs back in Ostutla, a monumental struggle he survived only by the grace of God.

“Also I found the drugs and told his mother,” María said. She was waving her hands over the bread to get it to cool.

“I did the worst things,” Esteban said. “I smoked marijuana.”

I began to count the number of images of the Virgin in the trailer. There were seven, up on the wall and on the table and above the sink. There might have been more in the bedroom down the hall.

Esteban sat by the oven helping María pack bread into plastic bags. They were down to one coil on the electric range, but the oven still worked fine. The trailer was intolerably hot, even with the air conditioner humming.

María and the boys began filling empty tomato cartons with bagged bread. Daniel munched on one; his mother waved her index finger at him admonishingly.

“We will be back in an hour,” María said, herding the boys out the door.

“Go with God,” Esteban said.

María pulled the little red wagon away from the front door and toward the gravel lane. Daniel kept trying to get in the back atop the piles of bread, but María shoved him off. I watched them through the window, which was clouded with dust. Finally everyone was settled, and they went off through the trailer park.

Esteban had seen many women peddle bread in Ostutla, but never María. Selling bread was for old women, Esteban said. But then, all women had seemed old to him when he was younger. I am old now myself, he said. He was thirty-five years old.

Esteban then told me the story of his becoming a man, and by becoming a man he meant becoming the sort of person willing to suffer indignities, sometimes for the greater good and sometimes merely because it fell to him with no explanation. He says he came to the United States and became a forgotten citizen of nowhere. He washed dishes and deboned chickens even as he imagined another life as a chef. When he had no work and María was away on a shift, he sometimes hiked to the chicken plant with Sara in his arms because the girl would not quit screaming and would take food only from her mother’s breast.

Esteban said there were two small roads that led to Ostutla, up in the highlands of Guerrero. The town is not on many maps. They walked everywhere on dusty paths. When it rained it rained too much and everything leaked except the houses of the old people whose sons sent money home. The sons could be anywhere — Costa Rica, Argentina, Nicaragua, America. Maybe China. When he was a boy Esteban thought he was not far from China, which of course was down the big hill and across the water. “How big is an ocean?” he asked me in explanation. “You don’t know.”

Ostutla was not for me, Esteban said. He must have been from somewhere else. Dirt did not stick to his shirts, he said. It was a mystery. The Church had been a mystery, too, at least to him. When he was young he learned to drink and smoke cigarettes. He did worse things, he said. In church everyone stood still and he could hardly stand it. He left María for a time after she discovered his marijuana and caused trouble with his mother. He found more marijuana, which he took to a little shed across town full of shovels and old Coca-Cola crates. He sat in the shed and smoked as much as he could until he thought he’d died. He had a vision of death, that it would be like sleeping, only your eyes would be open and you’d be forced to see everything forever and you wouldn’t be able to move. He stretched out on the floor and couldn’t get up. In that moment he couldn’t make his mouth go right, he couldn’t yell or talk, and he was very afraid. He told me he wouldn’t ever forget this. It’s his conversion vision, he said, though the full story of that conversion is more complicated. There had been much more struggle after that; the vision had been a kind of annunciation of what was to come.

This is the way of all visions, religious or not. Americans were the landless and ornery who pushed out from the coast, driving hogs before them, over the mountains (always a mountain), putting behind them their fellow citizens. And when they reached the big river, they crossed it and climbed into the next set of mountains. At every stop the pioneers shed some of their number, who lingered behind as instantiations of a human desire to put down roots, a desire not shared by those who went on. In this way a restless people bred themselves into travelers through frontiers where God appeared only in moments of clarifying strangeness.

The wayfarer is most happy when the world reveals itself in pieces, flashes, glimpses out a bus window and between the trees. The cascade retains its sublimity only so long as the observer remains unformed and on the move, the angle of observation unfixed. The traveler sees nothing unusual in the words of Daniel Boone: “Thus situated, many hundred miles from our families, in the howling wilderness, I believe few would have equally enjoyed the happiness we experienced.” In this desert the traveler sloughs off history like an old skin. But the traveler is a freak. We the settled turn ever back to the past, lost in the woods, pleading with the past, our founders, to preserve us from outsiders.

When Esteban had recovered from his bender and enshrined his vision in memory, he returned to María. He threw out the marijuana, and then the liquor, and then the cigarettes. They had their first three children, Arturo, Rafael, and Paula. The war between the paramilitaries and the narcotraficantes in Guerrero began to heat up, and Esteban had more visions of death.

Soon afterward they came to Chatham County. That was ten years ago.

Arturo never mentioned to me the subject of his call to holy orders. He appeared in every way a typical middle-school student: he wore chunky secondhand skater shoes and spiked his hair sometimes. Once, in a rare moment, he said he liked to fish, and sometimes fantasy novels spilled out of his book bag. I also learned, through a sheriff’s deputy I sometimes trusted, that Arturo enjoyed painting words and faces on the underside of the bridge half a mile away where the main drag crossed the railroad tracks. The huge concrete canvas wasn’t visible unless you bushwhacked through skunk weed and scrub pine down a steep incline, or hiked a mile or so up the railroad tracks from the center of town. Periodically the Department of Transportation would paint over the hieroglyphs, but it was never long before the intricate signs returned, offering clues as to who was still un gato, who could still kick your ass, and who was still in love with Lazy Smiley and his boy, Luny T. This didn’t seem part of the education of a priest, though it did seem a familiar American sort of education — that of the teenager declaring Here I am, I was here, I passed this way. Fewer than a hundred yards from the graffiti bridge lies the grave of Frances Bavier, Aunt Bee from The Andy Griffith Show, who lived about a mile from where the Almanzas’ trailer now sits. On her headstone is carved: to live in the hearts of those left behind is not to die. Shortly before her death, surrounded by her many cats and her dense hedges, Ms. Bavier gave an interview: “It’s very difficult for an actress or an actor to create a role and be so identified that you as a person no longer exist.”

A child like Arturo knows that the best thing to do, for now, is to stay out of sight. The threat is everywhere — of separation, arrest, and deportation. So he leaves his work unsigned, he paints in the dark and carries his backpack with him everywhere. My arrival disrupts the equilibrium. He sees a threat. His parents don’t see it that way, they don’t feel the threat quite as personally as the son does. They want to prove that they can talk freely without fear. The son thinks this is naïve, and it makes him angry. They don’t understand this place as well as he does, and they don’t read the papers.

María was at work when the cops came for her. She was on the line, as usual. They tapped her on the shoulder and she stepped away from her workstation. The line closed up behind her. She didn’t know why they were taking her, or precisely who they were, but she had always known she could be taken by someone.

Esteban was at work when he found out. He remembered receiving a call and then going to collect the kids into a neighbor’s minivan, one of those jalopies so old the paint had been flayed from the front hood by wind and sand. He remembered speeding down to the courthouse. Like all undocumented immigrants in North Carolina, he’s forbidden to have a driver’s license, and so he prayed against being stopped. He called Father Pedro for help, and it was Father Pedro who found the bail bondsman and, later, the lawyer. But what he remembered above all was seeing María shackled hand and foot, and realizing at that very same moment that he had brought the children, who would now see their mother in chains. This was foolish. He should have left them at home. But with whom? There was no one he could trust who wasn’t working.

Esteban thought, “This is a test. We must accept it and thank God for it.”

Esteban thought they shouldn’t treat María as a criminal: all she’d done was to go to work that morning and cut chickens. She would never run. Where would she run? The children were convinced she’d be taken away forever that day, and so they cried. María seemed so small. For the first time in many years, at least since the marijuana incident, he began to imagine being without her.

María’s beauty would be familiar to anyone who’s seen Orozco’s Cortés y La Malinche, a mural in Mexico City’s Colegio de San Ildefonso. María looked very much like La Malinche, Cortés’s guide and lover, the original Indian mother. It isn’t the architecture of the face so much as its expression, like that of the tentative and contained nude woman in the weird, chaste grasp of a ghastly white Cortés, the woman who trusted too easily and failed her people.

In the front rows of the courtroom the fearful and the possessed had gathered. The domestic abusers with striped jail gear and shaved heads mouthed off at their girlfriends, who stood quietly across the room. There was an endless parade of drivers who were drinking, drivers without licenses, drivers who were drinking and driving without licenses, underage drinkers. Some of the men had been getting into shoot-outs over underage girls. Behind them sat those caught with drug paraphernalia, the check kiters, the shoplifters, and the graffiti artists. White, black, Latino, all of them awkward in the way of people who know they must be on their best behavior but whose knowledge of that behavior is somewhat theoretical. They pay a lot of attention to their hands. They stand up in front of a man who doesn’t speak their language, who speaks a legal language that’s nominally English but is hardly comprehensible. They’re all ready to tell their life stories, the hundred different reasons why what they did wasn’t so terrible, and how they’ve since been renewed and redeemed.

The judge never wants to hear their exquisitely rehearsed bullshit; he barely lets them open their mouths. No chance to tell the court how they really aren’t as awfully broken as they appear. When defendants go free they’re sometimes so shocked they seem reluctant to leave.

If there is an American Experiment, this is where it stands at the moment: with María in the dock, with chickens squabbling and tossing feathers from the trucks, with old Mercedes diesel sedans rumbling by at all hours, with men climbing cell towers to mount their shortwave repeaters in advance of the coming revolution and the end of the world, with reports of barren circles where the Devil paces when we’re not looking, with futsal and catfish-spotting and the old Arabian horses out in the paddock too feeble to ride, with fracking and picketing and pickling and chemotherapy, with a man at Father Pedro’s church dressed up in plastic centurion gear to place a crown of thorns on Jesus, who that year was from Tabasco and sold mobile phones in Siler City during the week.

The Almanza children, from eldest to youngest, have been transformed. The link to their parents’ past is mostly broken. They are now American, peripatetic and animated by longing. Their parents lecture them about materialism, but it was their parents who packed up and walked out of Ostutla. In doing this they ratified the American notion that happiness is just one more transformation distant, one more trip down the highway with the trunk packed. Esteban and María’s children will someday disappear into America, if they can stay.

The last time I went to talk with the Almanzas, I brought María a used stove that a friend of mine had wanted to toss out. María’s had finally broken for good, and Father Pedro had been calling around trying to find one. The old stove slid out easily, and the new one just barely fit. Esteban promised to return the favor. We rested afterward at the kitchen table.

María had bonded out two hours after her arrest, which meant Immigration and Customs Enforcement didn’t have time to investigate her residency status. She’d been charged with identity theft, a felony, but her attorney arranged a deal with prosecutors: in exchange for pleading guilty to possession of a fraudulent identification, a misdemeanor, and making restitution to the victim, prosecutors would dismiss the felony charge. If all went well, María would face only forty-five days of a suspended jail sentence and six months of probation. This was the best possible outcome for her, but in order to pay the $8,000 they owed for restitution and legal fees, only some of which they could borrow from Esteban’s uncle, María would have to go back to work — illegally — to help raise the rest.

María disappeared into the back room and returned, pulling a card out of a little beaded purse. She held it out to me, and I saw a new identification card bearing a new identity. This time, at least, it was entirely fictitious and bore no Social Security number, license number, or other traces of a legally recognized citizen. She’d learned that lesson. Later, her friends and family would describe her terror at being caught again and her fear of even leaving the trailer. But she had few options; failing to pay the restitution would mean another arrest and probably deportation.

“I didn’t understand, I didn’t know it was another lady’s number,” she said. She told me that she would quit working at the plant just as soon as they’d raised the money. “I will come home and take care of the babies and bake my breads,” she said to me. She watched my eyes when she said it, as if they would tell her whether this was true or not.

Esteban came in from the grill, wiping his hands on his trousers, and I asked, “Why don’t you all just leave?”

Father Pedro shook his head at me. María got up to stand by the stove with her back to us.

I said, “You can go. They’ll get you, you know that, right? They’ll take the money and they’ll still get you. They’ll have you up in court again, as many times as it takes.” This seemed obvious, not even worth mentioning under other circumstances. They should have been gone days before, should have left this place in their dust. Pack up and move, it’s the only way.

Esteban nodded, as if he’d heard this before and had even considered it. He folded his hands on the table in front of him, as if he were giving testimony. In Father Pedro’s translation he sounded almost oracular:

“I believe in this nation, and I want to be faithful, to the courts and to the bondsman. I have faith in this country and in God. And I say no! If I returned back to our country I would not have the opportunity to accept what God sends me. We must accept this and thank God for it. I always tell my children I am happy to be the father of six children, and that their mother is very proud. I say, ‘We love you.’ And we are always prepared to accept what God gives us. I say to our children, when they ask me what will happen to mami, that God will not divide a family, a mother from her children. If I cry every day, my family will cry also. We are not going to rob or steal. We are not going to cheat to get this money.”

And then Esteban did begin to cry. His face flushed. He had to stop talking for a moment. Father Pedro put his arm on his shoulder and squeezed. We sat silently. Esteban recovered and began speaking again. Because he was nervous, he stuttered a little.

“The reason why God is going to permit us to remain here, in this country, is because I believe and hope that one of my children will consecrate themselves to God. My family is joyful here. I won’t be swayed by any group, I won’t give in to materialism. We have been changed already. We are converted. It is the only change that matters, and it is forever. And that is why we are willing to stay, why we are not running, and why we are trying to pay back the money we owe. We have faith in God and are willing to accept anything.”

It would have been cruel for me to tell him what I thought, which was that hardly anyone cared how much he wanted to be an American, that this was beside the point, and that among some Americans his desire to join them would itself be considered evidence of the threat he posed. If he thought he could carve a holy paradise out of this wilderness, I would not be the one to tell him otherwise.

After that our conversation dwindled to nothing. We sat at the table pulling at the roasted chicken Arturo brought in. We chatted about this and that; I went over to set the digital clock on the stove. Finally I made to leave. Esteban pumped my hand, thanking me for the stove. “It’s nothing,” I said. It was really nothing.

María hugged me, and even Arturo gave my hand a shake. I think maybe he knew I wouldn’t be back.

“If I have to go to jail for what I have done,” María said as I was leaving, “if I have to go to jail for this wrong thing I did, I am willing.”

Some months later, I drove back to the trailer park. Someone had strung decorative lights over the Almanzas’ doorway. I was ashamed that I hadn’t been back for a proper visit, so I stayed in my car out of sight. Father Pedro had been assigned up north to a place where he could hear confession all day (“It is like being a vessel of God!”) and had been gone a couple of months.

The chicken plant had been closed down by its owner, a Ukrainian petrochemical kleptocrat and poultry tycoon, and I assumed the Almanzas were out of work. And so I suppose there were only two things I expected to find: either they had left for a new place or Esteban hadn’t been kidding about their devotion to this one.

I hope someday there will be Almanzas to watch when Reno Sharpe’s store collapses on itself in a heap of gray wood, laying down a new local geology of grease and fifty-year-old bottle caps. This county has been disintegrating and remaking itself in one form or another since before our recorded history.

From my hiding place I saw Esteban come out back, wearing the same shirt he always wore. He started working on his car. This time Arturo was with him, and he appeared to know what he was doing. Esteban handed him wrenches and rags, and they seemed to be talking very seriously, man to man. After a while they cleaned up and went inside, and when they pushed aside the drape I thought I saw María for just the slightest instant.

I waited so they wouldn’t hear the sound of my car, and then I pulled out with the headlights off. I noticed they were running the air-conditioning. It had been an unusually warm fall day, and I could hear the window units thrumming throughout the trailer park and all the way home.