Discussed in this essay:

12 Years a Slave, directed by Steve McQueen. Fox Searchlight Pictures. 134 minutes.

“Someone must have slandered Joseph K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested.” So begins one of the most emblematic novels of the twentieth century and so, more or less, begins the most generally honored motion picture of 2013: 12 Years a Slave. Directed by the forty-four-year-old British filmmaker and video artist Steve McQueen from a screenplay by the American novelist John Ridley, itself based on an 1853 account of the same title, 12 Years a Slave is, like The Trial, a trapdoor over the abyss. Although less abrupt than Kafka’s novel, the movie wastes little time before plunging its viewer into a nightmare of dehumanization.

Eleven minutes after Solomon Northup (played by the British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor) has been introduced as a happy man with a family, a livelihood, and a comfortable home in bucolic Saratoga Springs, New York, he wakes to find himself in darkness and chains. Protesting his inexplicable condition, he is beaten with a paddle until the paddle, used because it leaves fewer marks than the whip, snaps. His earlier life has evaporated; his new reality is that of a black man in the antebellum South.

Northup’s book, transcribed from his oral account by a white man, the New York state legislator David Wilson, is notable among so-called slave narratives for its specificity in names, places, and dates. It is not only a blunt, detailed account of the physical and psychological terror with which America’s “peculiar institution” was maintained but also a chilling evocation of non-personhood, as Northup’s identity is obliterated entirely. The son of a former slave but himself born free, Northup was persuaded by two con men to accept work in Washington, D.C., and there was drugged, kidnapped, penned, brutalized, given a new name, and packed off to New Orleans to be sold as chattel.

Could it be possible that I was thousands of miles from home — that I had been driven through the streets like a dumb beast — that I had been chained and beaten without mercy — that I was even then herded with a drove of slaves, a slave myself? Were the events of the last few weeks realities indeed? — or was I passing only through the dismal phases of a long, protracted dream?

McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave is, like the book, an existential ordeal, but it is also by far the most visceral of those recent motion pictures responding to a unique actor on the public stage — Barack Obama.

There has long been a recognition that America’s presidents are the protagonists of some great national drama. JFK and Bill Clinton both inspired Hollywood cycles — glamorously angst-ridden and hyperbolic political melodramas in Kennedy’s case and tawdry action flicks in Clinton’s. LBJ’s war brought the rise of the “dirty” western; Nixon presided over innumerable TV and Hollywood policiers. Ronald Reagan appropriated the macho language of some blockbusters (Star Wars, Rambo) and inspired others, fanciful saber-rattlers like Top Gun, while the blithe denial of George W. Bush’s two terms found an analogue in cinematic fantasies of omnipotence — the rise of animated blockbusters and comic-book superheroes.

Even before Obama, a black president was not an unknown Hollywood trope. As numerous turn-of-the-millennium movies and TV shows made clear, an African American in the White House coincided with disaster. (In addition to Deep Impact, we have The Fifth Element, Stealth Fighter, the television series 24, the Christian-fundamentalist Left Behind, and Roland Emmerich’s multicataclysmic 2012.) A black man could become America’s president only once life as we knew it had come to an end (or was about to) — as with the crash of September 2008 that helped sweep Obama into office.

But Obama’s presidency has reconfigured the narrative, emphasizing the black man as an American protagonist and inspiring Hollywood to retell African-American history. “There’s a situation of authority which allows authority,” McQueen said of the age of Obama in a PBS interview. “We can tell our story now, because we are in a position of authority.” The 2012 Oscar season brought Steven Spielberg and Tony Kushner’s judicious Lincoln along with Quentin Tarantino’s outrageous Django Unchained, which depicts a slave’s rebellion by fusing the Sixties anti-American spaghetti western and the Seventies Black Power revenge film. The year 2013 saw a new Jackie Robinson biopic and the latest Roland Emmerich disaster film, White House Down, with Jamie Foxx (a.k.a. Django) playing a beleaguered president who, unlike Morgan Freeman or Dennis Haysbert or Danny Glover (or, indeed, Barack Obama), talks “black” and wears Air Jordans. As the film’s envious Speaker of the House complains: “Voters today want somebody cool.”

The panorama of post–World War II history known contractually as Lee Daniels’ The Butler normalized a black presence in the White House in another way, starring Forest Whitaker as a Forrest Gump–like figure who rises from near-slavery in the Deep South to serve Presidents Eisenhower through Reagan. In addition to 12 Years a Slave, 2013 fare included Black Nativity, an adaptation of Langston Hughes’s gospel passion play, also starring Whitaker; the docudrama Fruitvale Station, about state-sanctioned violence against a young black man; and historical documentaries on Muhammad Ali and the Philadelphia black-liberation MOVE cult. As Hollywood Reporter noted last November, “never before has such a diverse slate of black-led films performed so well at the box office as they have in recent months.” (The only “race” movie Obama associated himself with was Lincoln, which, in hopes of establishing some sort of consensus with congressional Republicans, he had screened at the White House.)

Yet there’s an especially modern, or at least modernist, aspect to Northup’s story, with its portrayal of the cosmic absurdity of fate. Published the year after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1853, 12 Years a Slave was a well-known abolitionist text and even a bestseller in the years before the Civil War. That it was, until McQueen’s film, less famous than other slave narratives may be due to Northup’s collaboration with a white amanuensis who many thought tidied up or even usurped his voice, sacrificing authenticity for literariness. More crucial to the book’s eclipse, however, may be the trajectory of Northup’s experience. The story of a free man sold into bondage runs disconcertingly counter to the more positive narratives told by Frederick Douglass and other ex-slaves. It is one thing to pity the travails of a person unluckily born into poverty, disadvantage, or slavery — and quite another to experience the plight of a free individual losing everything for no reason at all.

Born in London of West Indian parents, McQueen was a video artist for fifteen years before making his first feature, Hunger (2008). McQueen’s shorter pieces were confrontational, tactile, and often focused on the body (in many cases, his own). One shows the actress Charlotte Rampling in close-up as the artist’s finger probes her eye. Another uses a helicopter and a telephoto lens to explore the armpit of the Statue of Liberty.

McQueen’s gallery installations were both highly formal — using a Warholian sense of “real time” — and overtly political. A 2001 video shows the artist in a hotel room relaxing in the glow of a TV report on the dispatch of NATO troops to Afghanistan. In McQueen’s best-known video piece, the half-hour Western Deep, the camera accompanies an elevator filled with anonymous workers on a descent in near total darkness and silence miles into the depths of a South African gold mine.

Duration also plays an important part in McQueen’s feature-length movies, which are unusually concentrated on the physical suffering of the protagonists. Though McQueen’s interest in privation, brutality, and degradation can make his films grueling to watch, the films also leave the impression of having been grueling for the actors to make. Extreme experience is dispassionately offered up for contemplation. Hunger, which is set almost entirely inside Belfast’s Maze prison, opens with a shot of inmates rhythmically banging their cups — and holds it long enough to establish the movie as something deliberate, cool, and perversely musical. It ends with the jailed IRA member Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender) starving himself to death, a harrowing final movement informed by a thousand years of Christian iconography: the emaciated martyr lies on a prison-hospital cot covered with weeping sores and stigmatic lesions. (Fassbender lost forty pounds for the role.) Solemn music and crucifixion imagery abound as well in 2011’s Shame, but in that film Fassbender’s thirtysomething Manhattan office drone mortifies his flesh in another fashion. Enslaved by an insatiable appetite for porn, whores, and hookups, both cyber and actual, he’s a sex addict — utterly narcissistic and single-minded in his pursuit, which nonetheless offers him no release.

Although more conventional in form than Hunger or Shame, 12 Years a Slave is likewise a film about bodies in prison and in pain. It’s composed almost as a linked series of short films, not unlike McQueen’s gallery work. Most sequences are closely adapted from the text, though several scenes appear as nearly autonomous inserts. These include the opening, which introduces the enslaved Northup (now rechristened Platt), as well as a brief sequence in which Platt stumbles on a lynching in a sylvan glade to realize, as Primo Levi learned in Auschwitz, that “here there is no ‘why.’ ”

John Ridley’s screenplay has streamlined Northup’s chronicle to a few experiences, all of which McQueen dwells on much longer than is usual in a narrative film. The protagonist’s initial beating in a Washington cellar within sight of the Capitol dome, for example, is a movie within the movie. So is the scene in which, after Platt attacks and beats a cruel overseer, he is strung up by the neck to a tree branch and left to dangle for endless minutes with his weight supported on tiptoes. The length of this unbearable scene is emphasized by the calm flow of daily plantation life all around him.

As its title reminds us, 12 Years a Slave is about time passing as well as about times past. “The time of the slave’s world is increasingly disjoined from any standard sense of time,” as the scholar Sam Worley, writing about Northup’s chronicle, observed in the literary journal Callaloo. The slaves’ present is not their own; instead, they are “made to stay up all night dancing to entertain the master, work around the clock during the cane harvest, and work on the Sabbath.” Only once in 12 Years do the slaves articulate their own relationship to time — to, in fact, eternity. In a scene invented for the movie, the camera records Platt’s reaction at a fellow slave’s funeral as he submerges himself in the group-sung spiritual “Roll Jordan Roll.” (The historian Eugene Genovese used the same powerfully affirmative anthem to title his excellent examination of slave society.)

Still, scenes depicting the capricious nature of the violence slaves endured are at the heart of McQueen’s film. In his book, Northup distinguishes between good and bad masters and goes so far as to speak of “the bright side of slavery.” At one point, he even finds himself cast as a slave driver (though this is not something that McQueen, whose view is more systemic, includes in his movie). With the notable exception of the abolitionist carpenter played by Brad Pitt (the deus ex machina who enables Platt to regain his freedom, and whose scenes follow Northup’s narrative verbatim), the whites are either passive go-alongs submitting to what they take as God’s will or sadistic brutes enabled by a system that debases all.

In interviews, McQueen has declared his sympathy for the worst master Northup encounters, the cotton planter Edwin Epps (Fassbender again). For the filmmaker, Epps is another sort of prisoner, in thrall to his lust for the young slave Patsey, whom he repeatedly rapes and obsessively torments, driven by both love and a desire to extinguish its object — as well as by the need to placate his vindictive wife. (In a sense, Fassbender, who has spoken of his difficulty in playing Epps, is reprising his role as the tormented sex addict from Shame.)

Patsey (the Kenyan actress Lupita Nyong’o) is, the protagonist aside, the most important figure in 12 Years a Slave. It would seem, from Northup’s text, that he loved her as much as Epps did:

Patsey was slim and straight. She stood erect as the human form is capable of standing. There was an air of loftiness in her movement, that neither labor, nor weariness, nor punishment could destroy. Truly, Patsey was a splendid animal, and were it not that bondage had enshrouded her intellect in utter and everlasting darkness, would have been chief among ten thousand of her people. She could leap the highest fences, and a fleet hound it was indeed, that could outstrip her in a race. No horse could fling her from his back. She was a skillful teamster. She turned as true a furrow as the best, and at splitting rails there were none who could excel her.

Patsey is also the fastest and most dexterous at picking cotton, routinely doubling the amount brought in by the male slaves. Northup calls her “queen of the field,” a sobriquet bestowed in the film by the besotted Epps.

Patsey is also cursed. She is scarred with a thousand stripes, Northup writes, because “it had fallen to her lot to be the slave of a licentious master and a jealous mistress.” After one terrible beating, Patsey begs Platt to put her out of her misery. (The movie follows the book, although Northup’s language is ambiguous as to whether it is Patsey pleading for oblivion or Mrs. Epps demanding it: “Nothing delighted the mistress so much as to see [Patsey] suffer, and more than once, when Epps had refused to sell her, has she tempted me with bribes to put her secretly to death, and bury her body in some lonely place in the margin of the swamp.”)

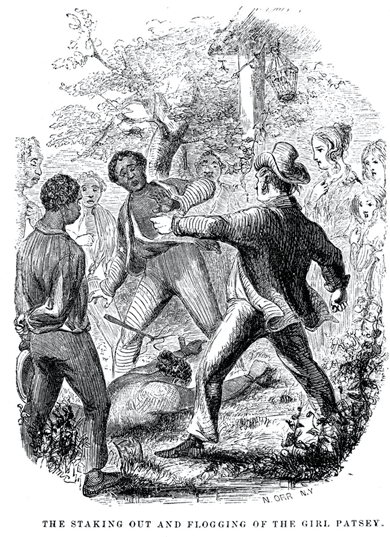

Gripped by an insane suspicion that Patsey is having a secret affair with a neighboring planter, Epps has her stripped naked and forces Platt to lash her before the assembled plantation hands. When Platt finally refuses to go further, Epps seizes the whip and in his frenzy beats Patsey gruesomely. Northup devotes the better part of a chapter to this ordeal, “the most cruel whipping that ever I was doomed to witness”; McQueen lingers on Epps’s violence and Patsey’s flayed back long enough to torment the audience. But Patsey is not permitted to die for our sins.

At the press conference that followed the screening of 12 Years a Slave at the New York Film Festival last fall, McQueen recalled his reaction when he first became conscious of the history of slavery. One might have expected him to speak of rage or disgust or sorrow. Instead, he spoke of his “shame and embarrassment.”

Shame is a central theme in McQueen’s work, but it has particular resonance in 12 Years. McQueen did not refer to, nor is his movie about, the shame of slavery (an institution for which “shame” is an insufficiently strong word). Rather, it might be said that 12 Years addresses the shame of the slave.

The embarrassment that McQueen experienced as a child is the recognition that one can be defined by the judgment of another. It is the helpless realization that, as Sartre put it, one is “no longer master of the situation.” Solomon Northup’s shame at being reduced to Platt is a vastly amplified version of the humiliation anyone might feel when cut down to a crude profile — when subjected to a police “stop and frisk” or shadowed by a department-store employee.

Viewers know that the movie’s protagonist will ultimately be freed. The title itself is a necessary spoiler. Like the Jews who found themselves on Schindler’s list, Solomon Northup is the great exception. Not one of the other slaves we encounter in 12 Years will escape slavery. In his heady moment of emancipation, Northup turns back from the wagon carrying him home; he meets the gaze of the movie’s most abused and hopeless character, the one to whom strength and beauty have only been an added burden and to whom even the relief of nonexistence has been denied: Patsey, a solitary figure who represents multitudes. We watch her watching Northup wave goodbye as he, who embodies the promise of freedom, forever vanishes from her world. It’s an ending that, however happy, is by Hollywood standards drastically muted.

Restored to his family, Solomon Northup’s first impulse is to beg forgiveness. His trial is over. But as Kafka concluded of Joseph K.’s, “the shame of it must outlive him.”