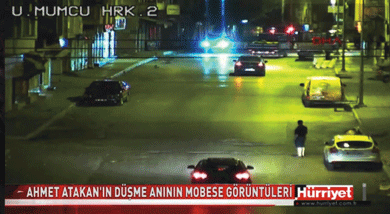

In 2005, the Turkish government launched a program called the Urban Security Management System (known by the acronym MOBESE), a network of CCTV cameras installed around Istanbul to monitor crime. MOBESE was soon expanded to cities all over Turkey, where its cameras remain a conspicuous piece of urban jewelry. By 2010 there were some 4,000 government cameras in 1,000 locations in Istanbul alone. “I think it is now possible for the state to follow someone from his home to virtually everywhere through CCTVs,” Kaan Karc?l?o?lu, an Istanbul attorney, told me. In the summer of 2013, when demonstrations to save Istanbul’s Gezi Park grew into the largest antigovernment protests in decades — a movement now referred to simply as Gezi — they were documented by MOBESE, by TV journalists, by mobile phones, and by private security cameras. On the night of September 9, a MOBESE camera was filming Gündüz Street in Antakya, a city near the Syrian border and the capital of Hatay province. Most of the frame is empty, but at the top right, red taillights mark a protest that has turned violent. Residents of the Armutlu neighborhood had gathered to oppose a new government development project and, as always, the brutality of the Turkish police. A few months earlier, a young protester named Abdullah Cömert had died on Gündüz Street after allegedly being struck by a tear-gas canister — the second Gezi fatality nationwide. Shortly after midnight, on September 10, in the faint red glow recorded by the camera, a twenty-two-year-old named Ahmet Atakan became the sixth. How Atakan died — whether hit by a tear-gas canister or after falling from a building — was a matter of controversy. When I visited his family at their apartment a week after his death, they said they planned to sue the police. His lawyer and supporters were picking over video footage for evidence. But the images were full of ambiguities, many of which seemed to be building a case for the police’s innocence. “Ahmet died exercising his human rights,” Nevzat Atakan, the victim’s uncle, said. “But I do not expect a positive outcome for us.”

Footage taken from a private security camera above a shop just north of where Atakan’s body was found shows a scattering of young men pacing or running along the street, sometimes congregating in loose huddles before an armed police vehicle called a Scorpion (Akrep, in Turkish) chases them into side streets. One protester saunters alone in the wake of a Scorpion and is narrowly missed by a sailing tear-gas canister. Atakan’s elder brother, Süleyman, released this video online as part of a thirteen-minute compilation trying to rebut the notion that Armutlu was full of protesters the night Atakan died. “I suppose it is the cars parked on the street that they call a crowd!” he wrote in a caption. “Residents and so-called crowds of protesters are panicking!” Atakan’s family seized on the storefront footage as proof that the police response was disproportionate. Similar images of other Gezi protests have been slow to materialize. Business owners with a good view, particularly those near Istanbul’s Taksim Square, have been pressured to turn over their footage to police. When a protester named Ali Ismail Korkmaz died in Istanbul in June 2013, police allegedly destroyed video of the incident.

Footage taken from a private security camera above a shop just north of where Atakan’s body was found shows a scattering of young men pacing or running along the street, sometimes congregating in loose huddles before an armed police vehicle called a Scorpion (Akrep, in Turkish) chases them into side streets. One protester saunters alone in the wake of a Scorpion and is narrowly missed by a sailing tear-gas canister. Atakan’s elder brother, Süleyman, released this video online as part of a thirteen-minute compilation trying to rebut the notion that Armutlu was full of protesters the night Atakan died. “I suppose it is the cars parked on the street that they call a crowd!” he wrote in a caption. “Residents and so-called crowds of protesters are panicking!” Atakan’s family seized on the storefront footage as proof that the police response was disproportionate. Similar images of other Gezi protests have been slow to materialize. Business owners with a good view, particularly those near Istanbul’s Taksim Square, have been pressured to turn over their footage to police. When a protester named Ali Ismail Korkmaz died in Istanbul in June 2013, police allegedly destroyed video of the incident.

“They shot him behind the left ear, and he fell,” Tolga Ocak, a teenage friend of Atakan, told me when I met him at a community center in Antakya. “After this they shot about ten canisters onto the street.” Ocak maintains that Atakan died, like Cömert, from being hit at close range with a tear-gas canister. “A half an hour before Ahmet died I counted fourteen or fifteen shots of tear gas,” Ocak said. “I was hiding in a small side street. I wasn’t able to talk at all, I felt almost dead, I couldn’t breathe.” After accounts like Ocak’s were repeated in Armutlu, word spread that the police had killed Atakan. Soon protesters across Turkey shouted, “We are all Ahmet!” to show their rage at the continuing police brutality. (Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, meanwhile, regularly praised the police.) According to Amnesty International, 130,000 canisters of tear gas were used in the first twenty days of protests. In addition to its primary function of dispersing crowds, tear gas also clouds video recordings. Partly because of this, the Atakan family lawyer was building a case against the police on the basis of eyewitness testimony. But just as tear gas can render a video useless, it can make the job of an eyewitness nearly impossible. The gas causes severe eye irritation, nausea, and breathlessness and can precipitate a heart attack — “and those are effects under ideal circumstances,” Vincent Iacopino, a senior medical adviser with Physicians for Human Rights, told me. “That’s not the way it’s used in Turkey.” Ocak granted that the gas could have impaired his senses: “When I ran to Ahmet, I couldn’t see anything.” But he stuck to the core of his story. “The police did it,” he said.

“They shot him behind the left ear, and he fell,” Tolga Ocak, a teenage friend of Atakan, told me when I met him at a community center in Antakya. “After this they shot about ten canisters onto the street.” Ocak maintains that Atakan died, like Cömert, from being hit at close range with a tear-gas canister. “A half an hour before Ahmet died I counted fourteen or fifteen shots of tear gas,” Ocak said. “I was hiding in a small side street. I wasn’t able to talk at all, I felt almost dead, I couldn’t breathe.” After accounts like Ocak’s were repeated in Armutlu, word spread that the police had killed Atakan. Soon protesters across Turkey shouted, “We are all Ahmet!” to show their rage at the continuing police brutality. (Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, meanwhile, regularly praised the police.) According to Amnesty International, 130,000 canisters of tear gas were used in the first twenty days of protests. In addition to its primary function of dispersing crowds, tear gas also clouds video recordings. Partly because of this, the Atakan family lawyer was building a case against the police on the basis of eyewitness testimony. But just as tear gas can render a video useless, it can make the job of an eyewitness nearly impossible. The gas causes severe eye irritation, nausea, and breathlessness and can precipitate a heart attack — “and those are effects under ideal circumstances,” Vincent Iacopino, a senior medical adviser with Physicians for Human Rights, told me. “That’s not the way it’s used in Turkey.” Ocak granted that the gas could have impaired his senses: “When I ran to Ahmet, I couldn’t see anything.” But he stuck to the core of his story. “The police did it,” he said.

There was another camera recording on the night of Atakan’s death. The police have released footage taken by one of the Scorpions as it drove down Gündüz Street. The chaotic video lasts for two minutes and shows the vehicles driving about three blocks. Trails of orange sparks follow the crack of tear-gas launchers; objects that appear to be stones or bricks hit the street and shatter into dust; the image lurches nauseatingly as the Scorpion swerves to avoid bits of failed barricades. Halfway through the clip, Atakan appears on the ground on the left side of the frame, his right arm flailing above his head, his knees curled toward his chest. In the hospital, after a long attempt to resuscitate him, doctors made notes of Atakan’s injuries. His limbs were intact but his spine had snapped. They removed 1.1 liters of blood from his lungs, his skull was fractured, and he was bleeding out of his left ear. Behind that ear the doctors found a wound, an “indented fracture,” of between five and six centimeters in diameter. Those with him in the hospital, mostly other protesters, friends, and his family, were convinced that he had been killed by a tear-gas canister — the wound behind the ear seemed a decisive bit of evidence. But Selim Matkap, the head of the Hatay branch of the Turkish Medical Association, told me the hospital staff could not determine what caused Atakan’s injuries. The video was likewise inconclusive: it showed Atakan rolling on the ground but not the force that had knocked him down.

There was another camera recording on the night of Atakan’s death. The police have released footage taken by one of the Scorpions as it drove down Gündüz Street. The chaotic video lasts for two minutes and shows the vehicles driving about three blocks. Trails of orange sparks follow the crack of tear-gas launchers; objects that appear to be stones or bricks hit the street and shatter into dust; the image lurches nauseatingly as the Scorpion swerves to avoid bits of failed barricades. Halfway through the clip, Atakan appears on the ground on the left side of the frame, his right arm flailing above his head, his knees curled toward his chest. In the hospital, after a long attempt to resuscitate him, doctors made notes of Atakan’s injuries. His limbs were intact but his spine had snapped. They removed 1.1 liters of blood from his lungs, his skull was fractured, and he was bleeding out of his left ear. Behind that ear the doctors found a wound, an “indented fracture,” of between five and six centimeters in diameter. Those with him in the hospital, mostly other protesters, friends, and his family, were convinced that he had been killed by a tear-gas canister — the wound behind the ear seemed a decisive bit of evidence. But Selim Matkap, the head of the Hatay branch of the Turkish Medical Association, told me the hospital staff could not determine what caused Atakan’s injuries. The video was likewise inconclusive: it showed Atakan rolling on the ground but not the force that had knocked him down.

Scorpions were an effective tool during the Gezi protests. Unlike TOMA trucks, white beasts with mounted water cannons, Scorpions are relatively small and fast but substantial enough to crash through barricades and protect the police inside. The Scorpion video supports the claim that protesters threw things from roofs and balconies. (Protesters have admitted as much.) And the video certainly does not show police shooting Atakan. But this isn’t what Armutlu residents saw in the footage. They saw the Scorpions and the canisters shot frequently and at dangerous angles. “One thing for sure is, there was a massive amount of tear gas,” Atakan’s brother Süleyman said. Some viewers offered a new theory: perhaps Atakan had been hit by a Scorpion. Selim Matkap — who acted out various scenarios for me in an elaborate, body-twisting pantomime — said that the wounds could be consistent with the impact of a Scorpion, or maybe not. He could have fallen from the roof, or been hit by a canister on the street, or not. The video provided few details about how Atakan died, but it left his supporters with great clarity about the police. To them, it was more proof that the authorities were the aggressors. Luckily for the police, they weren’t the only ones filming that night.

Scorpions were an effective tool during the Gezi protests. Unlike TOMA trucks, white beasts with mounted water cannons, Scorpions are relatively small and fast but substantial enough to crash through barricades and protect the police inside. The Scorpion video supports the claim that protesters threw things from roofs and balconies. (Protesters have admitted as much.) And the video certainly does not show police shooting Atakan. But this isn’t what Armutlu residents saw in the footage. They saw the Scorpions and the canisters shot frequently and at dangerous angles. “One thing for sure is, there was a massive amount of tear gas,” Atakan’s brother Süleyman said. Some viewers offered a new theory: perhaps Atakan had been hit by a Scorpion. Selim Matkap — who acted out various scenarios for me in an elaborate, body-twisting pantomime — said that the wounds could be consistent with the impact of a Scorpion, or maybe not. He could have fallen from the roof, or been hit by a canister on the street, or not. The video provided few details about how Atakan died, but it left his supporters with great clarity about the police. To them, it was more proof that the authorities were the aggressors. Luckily for the police, they weren’t the only ones filming that night.

Several hours after Atakan died, Akdeniz TV released a video taken by one of their cameramen. He had been filming on Gündüz Street, behind a low barricade made of trash. As the Scorpions race down Gündüz amid the noise of protests, a dark mass falls through the upper-right corner of the frame. It is slack and unmoving and perpendicular to the ground before impact. The video satisfied Turkish officials. Atakan had not been hit by a tear-gas canister, the governor of Hatay announced, but had fallen from a roof. Turkish media broadcast the video in slow motion with Atakan’s body circled in yellow. Government supporters claimed that Atakan had been throwing objects — stones, solar panels — onto the street before he fell. The young Akdeniz cameraman, who was part of Atakan’s social circle, wouldn’t leave home out of “shame,” one of his friends told me. In Armutlu, though, there was a bitter denial that the video proved anything. The image is grainy, shot at a distance and at night. Many, like Ocak, believed that the video had been manipulated in order to exonerate the police. Others thought it possible that Atakan had fallen from a roof, but only because a tear-gas canister had knocked him off. “It’s clear that he is unconscious,” Süleyman told me. But why were none of the satellite dishes or laundry lines in his path damaged? Why were the fractures in his neck and head only? “It’s clear something is falling,” Süleyman continued. “I don’t know whether it is my brother or not.” But the autopsy results were consistent with a fall, according to both Matkap and a leading American forensic pathologist who watched the videos and discussed the injuries with me (and who asked to remain anonymous). “I’m not sure a tear-gas canister had anything to do with it,” the forensic pathologist said. A canister found near where Atakan landed and presented to the authorities with much hopefulness turned out not to carry his blood or hair.

“Police officers were repeatedly seen firing tear gas canisters horizontally at suspected demonstrators as a weapon,” reported Amnesty International. “[P]hotographic and video evidence also point to the frequent use of tear gas against protesters fleeing police.” In this image, taken from the Scorpion video, an orange streak coming from a Scorpion looks to be nearly horizontal to the ground. A moment later the same Scorpion fires two shots at a steep angle, upward. Tear gas is intended to be fired at a forty-five-degree angle. “Once you use tear gas incorrectly, it effectively becomes a lethal weapon,” said Emma Sinclair-Webb, a senior Turkey researcher with Human Rights Watch. Videos showing police misuse of tear gas could aid Atakan’s family if they sue the government. But catching the police and protesters on camera often backfires. “It’s important to record police abuses,” Andrew Gardner, Amnesty International’s Turkey researcher, said, but “in the past the state has used video evidence against people taking part in the demonstrations.” Turkish law allows for demonstrations without prior approval as long as they are “peaceful,” but the term is loosely defined. “The thousands of people arrested at the protests — the evidence against them is often going to come through video evidence,” Gardner said. Can Atalay, a lawyer with Taksim Solidarity, suspects that Gezi’s seasoned protesters destroyed the cameras in Taksim Square themselves. “It’s a protest against Big Brother,” he said, “and they were technically part of a big demonstration. Obviously they didn’t want to be watched and recorded.”

“Police officers were repeatedly seen firing tear gas canisters horizontally at suspected demonstrators as a weapon,” reported Amnesty International. “[P]hotographic and video evidence also point to the frequent use of tear gas against protesters fleeing police.” In this image, taken from the Scorpion video, an orange streak coming from a Scorpion looks to be nearly horizontal to the ground. A moment later the same Scorpion fires two shots at a steep angle, upward. Tear gas is intended to be fired at a forty-five-degree angle. “Once you use tear gas incorrectly, it effectively becomes a lethal weapon,” said Emma Sinclair-Webb, a senior Turkey researcher with Human Rights Watch. Videos showing police misuse of tear gas could aid Atakan’s family if they sue the government. But catching the police and protesters on camera often backfires. “It’s important to record police abuses,” Andrew Gardner, Amnesty International’s Turkey researcher, said, but “in the past the state has used video evidence against people taking part in the demonstrations.” Turkish law allows for demonstrations without prior approval as long as they are “peaceful,” but the term is loosely defined. “The thousands of people arrested at the protests — the evidence against them is often going to come through video evidence,” Gardner said. Can Atalay, a lawyer with Taksim Solidarity, suspects that Gezi’s seasoned protesters destroyed the cameras in Taksim Square themselves. “It’s a protest against Big Brother,” he said, “and they were technically part of a big demonstration. Obviously they didn’t want to be watched and recorded.”

Fights over video footage have marked the Gezi protests since the beginning. Each side accuses the other of destroying cameras and editing clips to suit its own ends. “The prime minister is saying, ‘Protesters came to Dolmabahçe Palace to kill me,’ ” Esra Arsan, a professor of journalism at Istanbul’s Bilgi University, told me. “Then we must see some footage, but there is nothing . . . When someone claims they were tortured or psychologically disturbed [by the police] they cannot prove it, because all the cameras are broken in the police station. Their use of surveillance is so hypocritical . . . they try to destroy all evidence of their wrongdoing. They say they are recording the truth, but they are hiding the truth.” Twenty-two seconds after Atakan’s body rolls into the frame, the Scorpion camera turns away. For half a minute more, while the action continues audibly to the left, the camera films Armutlu’s still, shuttered storefronts. In Gezi Park — as with protests across the country — when traditional media failed, protesters trained their mobile-phone cameras on the police. They were proud of their ability to document the government’s brutality. Videos show police officers shooting tear gas into enclosed areas; they show police beating protesters; they show crowds that include children and the elderly. But they don’t show everything. In many videos, police identification numbers, normally displayed on helmets, are covered, or the cops are in plain clothes. All too often, as in this portion of the Scorpion video, the action is just offscreen. Atakan’s family, for their part, could barely watch the videos from September 9 and 10. What they showed, the family already knew. “There could be many things that caused his death,” Atakan’s uncle said. “But the reality is, if the police hadn’t been there, Ahmet wouldn’t have died.”