I met her in a computer course my sophomore year at NYU, in 1981. It was the first day of class, and we were learning how to connect the terminals on our desks with the mainframe: we had to dial a number and insert the phone handset into a bulky modem, after which it would emit a series of tones of varying frequencies and speak to its master. The girl next to me was having difficulty making the apparatus work, and she turned to me for help. I didn’t know much about computers, but as an Indian I was expected to know. I got her through.

“Thank you! Can I have your number, in case I need help with the homework tonight?”

She had laughing brown eyes, dark hair cut short in a bob, a Carib Indian cast to her cheekbones, and a mouth made for sin. Her name was Nina, she said. It wasn’t; it was Natalia, I found out much later, the first of the evasions or adornments or embellishments that marked all her stories.*

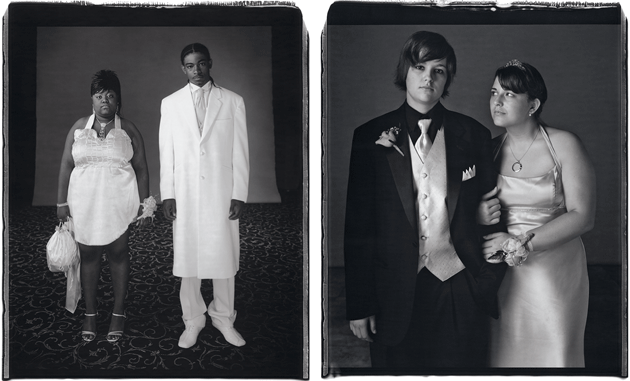

“Nikkia Simmons and Isiah Merrill, Malcolm X Shabazz High School, Newark, New Jersey, May 18, 2006” and “Miranda Banks and Candice Martin, Charlottesville High School, Charlottesville, Virginia, April 26, 2008,” by Mary Ellen Mark, from her monograph Prom (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

That night she called me. After we got business out of the way, we chatted about NYU, where she had just started business school. She seemed, in her Latin manner, easy and approachable. I asked her what she was doing that Saturday night. I asked if she’d like to go with me to a Broadway play.

The university gave its students discount vouchers to plays that had been extended past their natural runs, or that nobody wanted to see, or that had too much dialogue and not enough music. One of them was a one-man show performed by Dave Allen, an Irish comic who had a series on PBS.

“Sure,” she said. I put down the phone quickly, before she could change her mind.

I had come over from Bombay with my family to Jackson Heights when I was fourteen. My parents sent me to an all-boys Catholic high school in Queens. There was nothing in the way of sex ed in the school, except when we were told about the evils of abortion in religion class or when the gym teacher urged us not to masturbate. “Don’t do it,” he said. “It’s sticky and attracts flies.” The only woman in the school was the secretary to the headmaster; she was in her fifties and had a stolid, pale face and always wore her hair up in a bun. When she walked across the commons room, the space erupted in a series of feral catcalls and comments on her skirt, her heels, her legs. We were convinced she kept the job in this miserable institution solely so that she could be the exclusive recipient of such rampaging male attention; nobody would look twice at her on the street immediately outside the school.

My knowledge of sexuality came mostly from the pages of the porn magazines in the back of my best friend’s uncle’s candy store, in Astoria. The first naked woman I saw in the flesh was a bespectacled Caribbean stripper in London the summer I turned eighteen. When I got back to New York, I went with my friends to another peep show in Times Square, where obese naked black women clutching dollar bills wandered around a stage surrounded by booths whose inward-facing walls had two sets of holes: one for the eyes, and one for hands, which we thrust out as the women asked, “Wanna touch, wanna touch?” If a hand held out a dollar, the woman came closer to the hole, and the hand poked and groped as fast as it could before the flesh it was probing moved on to the next hole.

I lived at home all through college; there was never even a discussion about whether I’d be allowed to live in the dorms. After my phone call with Nina, I asked my father for permission to stay out late; he looked up from his newspaper and asked me where I was going, and who with.

“I . . . I’m going out with a friend.”

“Which friend? Minesh?”

“No, it’s . . . a girl in my computer class.”

There was a pause, and I steeled myself for his fury.

“Come with me,” he said. I followed him out the front door and to the Spanish menswear shop on 37th Avenue. He asked the oleaginous attendant to fit me out. “This is an important social occasion,” my father explained. I showed up for my first date wearing a three-piece suit.

The Irish comic sat on a chair onstage. He held a glass of whiskey and cracked jokes about drinking too much of it. “Why am I always flicking my shoulder like this?” He flicked his shoulder. “It’s because the little people start climbing up me arm after I drink.”

Afterward we went out to Raga, the best Indian restaurant of the time, and I ordered everything on the menu: tandoori chicken, naan, palak paneer, and on and on. Scotch and soda, a bottle of wine. Then desserts. I could eat only about three bites of the vast spread, although I did justice to the alcohol. We left most of the food on the table when we got up.

From the restaurant, we walked to the skating rink at Rockefeller Center and sat on the benches there. We could smell the flowers planted in the half-light behind us. There was nobody there at that hour but us. Nina turned her face to me and smiled. With fear and trembling, I kissed her — or did she kiss me? For the first time in my life, I felt someone else’s tongue enter my mouth. High above Rockefeller Center, I floated.

We started dating. We would go to movies in the student center and make out in the theater’s balcony, hardly remembering what movie we were seeing. We sat in Washington Square Park and kissed publicly, demonstratively. I found everything about her background entrancing — her Brooklyn-Spanish accent, her stories about the tortured history of the Dominican Republic. She took pains to distinguish herself from the throngs of darker, lower-class Dominicans who predominated in New York.

“Can you find a place we can be together?” she asked a few weeks after that first kiss. “I’m a woman, I can’t live without sex,” she said, in invitation and warning. If I didn’t have sex with her soon, I’d lose her. And then I’d be like all the other womanless Indian geeks at NYU. Having a girlfriend made me feel special, more American.

I turned to the Sharif brothers, a pair of Indian Muslims who had been with me in high school; Bunty, the younger brother, was also attending NYU. They ran the family garment emporium on Broadway, where they’d cut out a hole in the dressing room to spy on female customers trying on the gorgeous Indian dresses for sale. The brothers had an apartment of their own in a modern condominium building on Lexington Avenue, in Curry Hill, and they gave me the key.

I planned my conquest carefully, as best as I could using what I had gathered from pop songs, TV sitcoms, and men’s magazines. Nina and I got to the Sharifs’ place right after they’d left in the morning. I put on a tape of my favorite album, Simon & Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits. We kissed for a while, sitting on the living room sofa. Then I rose, held out my hand.

“Shall we go into the boudoir?”

“The what?”

I led her into the bedroom and deposited her on one of the two single beds. “Excuse me while I change into something . . . more comfortable.”

When I returned from the bathroom, in a paisley smoking jacket, she laughed so hard I thought I’d blown my chances. But then my Nina opened her arms, one unlikely American embracing another. And, as two boys from Queens sang, “Coo coo ca-choo, Mrs. Robinson,” Nina called out, “Ay papi. Coño. Carajo.”

The buzzer rang. It was Bunty Sharif, demanding to be let back into his apartment. We gathered up our clothes and fled. Nina took me to a restaurant down the block — not an Indian one — and ordered a hamburger, cut it up with a fork and knife, and fed me sections of it with her hands.

After the ice had been broken, we fucked anywhere we could in the nooks and crannies of NYU: in the study carrels of Bobst Library; in the stairwell behind the fire exit at the top of the Loeb Student Center; in my car; on a subway platform with her skirt hiked up, leaning against a pillar; and, most of all, in various offices of the student center, where my desi friends and I had formed a consortium that trafficked in spaces where we could drink and have sex. NYU was desperate for student clubs that would belie its reputation as a commuter school for Jews who couldn’t get into the Ivy League, and so if you got together five students, the university would give you $500 a semester and a room of your own in the Student Activities Building.

My Indian friends and I were all living at home with parents who were fearful of corruption, addiction, and miscegenation. Eighty-six percent of Indians in America marry other Indians. Our parents were afraid of the other 14 percent. Once, while I was dating Nina, my mother, chopping vegetables in the kitchen, said to me, chop-chop-chop, “If you marry an American,” chop-chop-chop, “take this knife,” chop-chop-chop, “and stab me in the heart with it.”

So we formed clubs: the Asia Society, the Cricket Club (our stadium was the sixth-floor hallway), and, in an inspired stroke, the Meontic Society (meontic meaning “what is not there”). The administrators didn’t notice that the clubs did nothing; they gave us the money, and we used it to drink screwdrivers out of tennis-ball canisters. The offices smelled perpetually of sex. People lost their virginity on the institutional sofas.

The Asia Society was composed of Indians from families in which the fathers expected their children to be home by nightfall and called the other fathers if they weren’t. Many of us were involved in impossible loves. Milind was in love with his sister-in-law’s sister, but her parents didn’t want two sisters to be married into the same family. They announced that an astrologer had determined the couple’s horoscopes to be mismatched, and so Milind and their daughter had to stop seeing each other. Soni’s father, who owned a fleet of taxicabs in Staten Island and hosted Punjabi separatists in his house, found out that his daughter was seeing a Hindu (the mother of the boyfriend called anonymously to tell him so). He promptly shipped his daughter off on the next plane to India, and she found a Sikh husband waiting for her in Amritsar.

We learned how to lie, and covered for one another. We said we were at the homes of our friends of the same sex. We lied about where we were, what we were doing, and who we were doing it with. We made up courses we were taking during the summer so that we could be out of our parents’ homes early in the morning and return late at night. We lied even when we didn’t need to, because it was easier, or perhaps because we’d gotten so good that it became a challenge to invent ever more implausible scenarios.

The more conservative the home, the wilder the girls were when they finally got out. There was Sheetal, the daughter of my family’s (Hindu) insurance agents, who fell in love with the dashing Sikh manager of the Deluxe Theater in Woodside, which showed Bollywood movies. When her parents found out, they dispatched her to relatives in Bombay for the summer to safeguard her virtue on what we called a “virginity vacation.” In their plush flat, she gazed out forlornly toward the sea. A young man noticed her from the neighboring balcony. By the end of the summer she was pregnant.

Mostly the Asia Society hosted parties. There were movie nights, for which Minesh and I would drive out to Queens Boulevard to pick up heavy 35-mm canisters from the dark office of the film-rental company. And then there were the dance parties in the auditorium, massive events with hundreds of people coming from colleges and high schools all over the area to dance to English new wave, disco, and Bollywood. And to drink: the drinking age was eighteen, and nobody bothered to card. There were always more men than women, and there were always fights. At a Chinese students’ party, two Chinese gangs — the Ghost Shadows and the Flying Dragons — started fighting, first with fists, then with guns. A fourteen-year-old Shadow was chased by Dragons into the laundry room of a dorm and shot dead. All our parties were shut down for a while after that.

One day, after Nina and I had sex in a friend’s apartment while he and his family were at work, we sat in a bar near the Jackson Heights bus station, and she ordered a manhattan for herself — she always went first — and another for me.

“I have something to tell you,” she began. “I’ve been married before.”

She was born and raised in Brooklyn — she had a strong South Brooklyn accent — but when she was sixteen, on a visit to the D.R. with her mother, she’d entered one of the island’s numerous beauty pageants. She caught the eye of a powerful politician named Brinio, and within a few weeks they were married. He was a member of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD), led by the blue-black Peña Gómez, and people said he would be vice president if the PRD came to power. But once they were married Brinio was often sought by the military, and she would have to hide him and lie to the soldiers who came looking for him at their home.

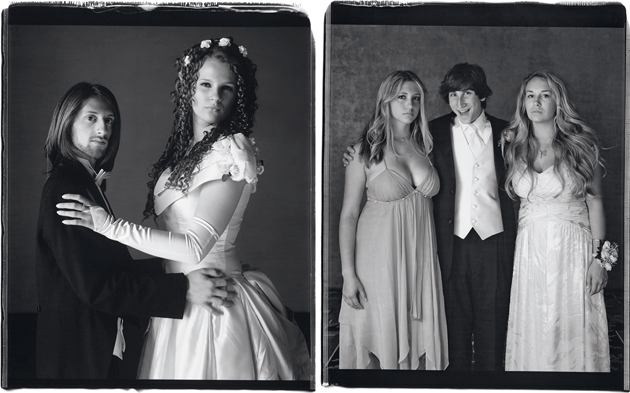

“Michael Glorioso and Eliza Wierzbinska, Tottenville High School, Staten Island, New York, June 16, 2006” and “Katie Barcay, Zack Goldman, and Mary Amato, Harvard-Westlake School, Los Angeles, May 17, 2008,” by Mary Ellen Mark, from her monograph Prom (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

A couple of years later, on Valentine’s Day, the phone rang in her house, and when Nina picked up, a woman demanded to know where Brinio was. “Tell him I’m waiting for him in the hotel room,” the caller said.

Nina divorced him and took up with a young German named Hans who was closer to her own age and attached to his country’s embassy. He would drive her on his motorcycle to the beaches of the island, play his guitar, and make love to her. Then she came back to New York to get a college degree. But her ex was still in touch with her, and he sent her money. Nina was grateful to him: “He gave me his name.”

She never invited me to her apartment, in Ditmas Park, where she lived with her mother. I didn’t meet any of her friends. Once, when she had to run an errand at the home of a friend, a gentleman who knew her in the D.R., she asked me to accompany her. There was a blizzard outside, but I tagged along faithfully. At the apartment building she asked me to wait in the lobby. “My ex’s bodyguards are following me. If he finds out I’m seeing someone we’ll both be in danger.”

Nina’s previous lovers had been, for the most part, powerful, rich men. The whole time I dated her, I always paid. I went to NYU on a generous scholarship, and the university gave me an annual stipend, which my father took control of, doling out $5 a day for my expenses. The little brass subway tokens cost 75 cents, and the lunch special at the Punjabi place on Bleecker Street, with unlimited sides, was $2.99. After a morning of strenuous tennis, my friends and I would swarm into the restaurant like locusts. The owner pleaded with us to eat less.

Whenever I had extra money, I took Nina to Panchito’s on MacDougal Street and ordered banana daiquiris, an obscene $5 each. I saved up my allowance for my dates, as my male friends also did for theirs. When it was just the boys, we would buy a loaf of white bread and a bag of chips from Gristedes, steal packets of ketchup from McDonald’s, and eat potato-chip sandwiches to stave off hunger.

My new country was munificent in unexpected ways. One Sunday morning I was doing my homework, and the radio was tuned to a pop station, WNBC 66. With the music thumping in the background, the DJ announced a giveaway: the sixty-sixth caller would get a prize. On impulse, I called. The DJ picked up.

“Congratulations! You’re the sixty-sixth caller! What’s your name?”

I gave it.

“Whatever. You are the lucky winner of sixty-six Arby’s roast-beef sandwiches! Whad’you think of that?”

There was a pause, and hundreds of thousands of listeners all over the Tri-State Area waited for me to respond with appropriate exultation.

“I’m Hindu,” I said.

There was another pause. The DJ swore under his breath.

“Tough luck. That’s what you’re getting.”

An envelope arrived in the mail with coupons for sixty-six sandwiches. At the time, I ate meat, and I was always hungry, so I took Minesh out to an Arby’s. The sandwiches weren’t just roast beef; they were “au jus,” which meant they came with a little plastic tub of grease into which you dipped the torpedo-shaped sub, the flesh of the long-dead animal soaking in the fat of other members of its species. When I took a bite, I understood why they were giving them away.

But here was a solution to my dating-budget problems. I would take Nina out for as many of the sandwiches as she could stomach, then give my father the rest of the coupons. He took his secretary out for lunch.

A few months into our relationship, as I was sitting with Nina at a bar, she asked the waiter for a manhattan and said to me, “You know how when you callmy house you hear kids’ voices? And I tell you they’re the neighbors’ kids? Well,” she said, taking a sip of her manhattan, “they’re not. I have an eight-year-old son.”

The next day I was miserable, thinking I was going to break up with her. “I’m dating a mother,” I thought.

But I stayed. You know the line in Dylan’s “Just like a Woman,” “I was hungry, and it was your world”? It was like that.

Around this time I began taking classes outside the business school. One of them was Introduction to Philosophy, taught by an assistant professor named Hannah. Hannah was attractive, Jewish, intellectual, with oily black hair and thick glasses. She inflamed me with her talk of Plato and Aristotle. I had recently discovered coffee, and a single cup with four spoons of sugar sent me soaring. I would drink it sitting in the front of the room, and much of each ninety-minute class was a private conversation between me and her, as the other students dozed off. One day, when I lingered after class as usual, she asked me to walk with her to the post office.

I was supposed to meet Nina in front of Bobst. She saw me walking by with Hannah, entranced by a conversation about Descartes and justified true knowledge. Afterward, when I went looking for Nina, she had disappeared. When I called her that night she said, “Something died in me today.”

Soon after that, Nina asked to go for a drive. I picked her up at school in my parents’ Caprice Classic and we drove to Flushing Meadows. We sat there in the car we’d had sex in so many times.

Nina stared into the rearview mirror. “I have to leave you. Because I’m older than you and in ten years you’ll look at me and you’ll look at yourself in the mirror and you’ll leave me. So I’m leaving you now, before you leave me then.”

I protested, I pleaded. I had spoken to my uncle about the possibility of marrying her, even. We could work it out, we really could. But she had made her decision.

Day after day I waited for her in the sixth-floor lounge. Or I waited for the phone in the lounge to ring; it might be her, and I was afraid to go to the bathroom in case I missed it. But day after day she did not come. My friends went, couple by couple, into the Asia Society office, and came out flushed and beaming. I sat on the sofa outside, taking my place among the computer geeks, the South Indians, Bunty Sharif. There was the weird Trini kid who wore polyester shirts with the first several buttons undone, showing his skinny, dark, hairless chest. He continuously combed his hair in front of the mirror in one of the student clubs, saying over and over, “Lookin’ good! Lookin’ good!” All around us, all over Greenwich Village, people were getting laid. “Poverty in the midst of plenty,” observed Dilip the Marwari MBA student. “Don’t you look at my girlfriend,” Supertramp sang from the lounge boombox. “She’s the only one I got.”

Everything having to do with love acquired multiple resonances. I read and reread the Gilbert Sorrentino story “The Moon in Its Flight,” which is about a Catholic boy from Brooklyn in love with a Jewish girl from the Bronx. Driving aimlessly out onto Long Island I listened to Pankaj Udhas’s ghazals about lost love. Nina always had mysterious older Latin men chasing her, and the Eagles’ “Lyin’ Eyes” became too painful for me to hear.

I fancied that she was the most beautiful girl in the world and that everyone wanted to fuck her. I fancied that she was fucking my friends. There was a charming Ismaili business student named Karim; I had noticed her laughing when I’d introduced them. I sat in my Jackson Heights bedroom and little porn loops ran through my mind of Nina doing all the things she had done with me, but now with Karim in a fancy condominium somewhere in Manhattan. His own place.

A few months after she broke up with me I was at the registrar’s office waiting in line to sign up for courses. My Trini friend Jude was working at the counter. He looked up her records. She wasn’t five years older than me, as she had said; she was nine years older. This time there was no manhattan to cushion the shock.

One fall day, almost a year after she broke up with me, Nina came to the lounge of the sixth floor, looking for me. She asked me to sit with her in Washington Square Park. We sat on the bench where we had made out so often, amid the derelicts and the drug pushers with their insistent “Smoke smoke smoke.”

Nina brought me up to date on her life. After she left me, she’d taken up with a Hispanic man who owned a chain of radio stations and a penthouse overlooking Central Park. They were engaged; she showed me the ring. But the previous night she’d come home to the penthouse earlier than planned, and found her naked fiancé snorting coke and masturbating over Polaroids of the women he’d been with.

“I feel like I’m a little bird up the tree and I’ve fallen out of the nest and I need you to catch me,” she said.

I listened, not saying anything.

“I’ve been shopping,” she said. She opened her bag and pulled out a set of leopard-print underwear.

We checked into a cheap hotel on 8th Street and fucked the rest of the day. The next day I called her and told her I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t catch her.

But after a year, Nina called again. She asked me to meet her at her office, at a radio station in Times Square, when she got off work. She came to the lobby dragging a large garbage bag that contained a frozen turkey. The owner of the station had given each employee a turkey for Thanksgiving, and she brought hers into the restaurant where we ate. She gave me a stock tip — OCI Technologies — “All the people at work are buying it.” The next week it doubled in price. She was still dragging the turkey when, underneath the lights of Times Square, we kissed goodbye.

We met once a year for a few years after that. The last time, she finally took me back to her place, and this apartment that I had so often tried to imagine became real, and then inconsequential. The last time we met, she came back to the place I shared with a group of louche Indian artists in Prospect Heights. We had sex, and then she left. I didn’t call her the next day. I had a crush on my roommate, an Indian girl from Iowa. “Don’t ever get old,” I told her.

A year later, I was married and living in New Brunswick, New Jersey, where my wife was in college. The phone rang.

“Hi! It’s Nina. I got your number from your parents.”

She had been watching a Latino news program and saw footage of a funeral in the D.R.: her ex-husband had been assassinated. Then she found out that he had left her six companies, including a bank. “I’m driving to Fort Lee, where I have a condominium, in my new BMW. Can we meet?”

I told Nina I was going to Boston for a trip and promised to call her when I got back. She gave me her number, and I wrote it down on a piece of paper.

When I hung up, I took the paper, tore it up into very small pieces, and flushed them down the toilet.