Discussed in this essay:

Patriotic Betrayal: The Inside Story of the CIA’s Secret Campaign to Enroll American Students in the Crusade Against Communism, by Karen M. Paget. Yale University Press. 552 pages. $35.

The revelations that the National Security Agency secretly gathered information on millions of us at home while the Central Intelligence Agency systematically tortured prisoners overseas have made it tempting to assume that such arrogant excesses are somehow novel. But Karen Paget’s Patriotic Betrayal brings to life a similar scandal from half a century ago. It’s a scandal that has great relevance today, and one for which, as it happened, I had something of a ringside seat.

Paget met her husband when they were undergraduates at the University of Colorado, where he became student-body president. Together they attended the 1964 conference of the National Student Association, in Minnesota. Delegates came from all over the country, as if for a presidential nominating convention. Paget, who grew up in a small town, says the experience opened up an “astonishing world” for her: “I was riveted by the political speeches,” she writes. “I had never seen or heard anything like it. I had grown up more devoted to cheerleading and baton twirling than political or intellectual pursuits.”

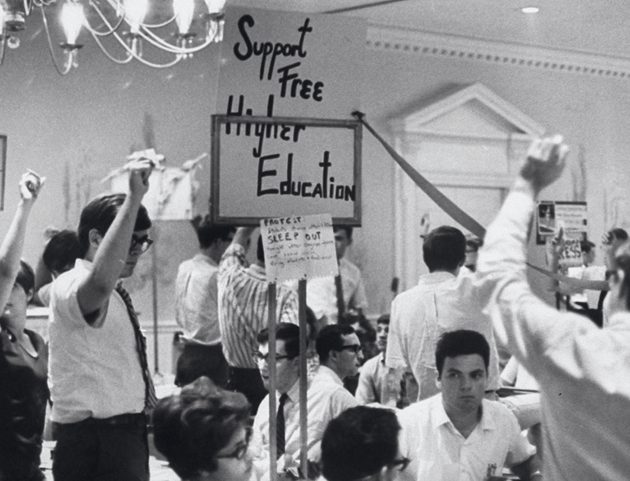

Photograph of a National Student Association meeting, September 1966 © Gerald R. Brimacombe/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

For several decades after the Second World War, national student unions were where the young and ambitious tried out their political wings. Barney Frank, Olof Palme, and Kofi Annan were all active in their countries’ organizations. In the United States, the National Student Association represented some 400 American campuses at its peak during the Cold War, when the role of such groups was greatly magnified. Both the United States and the Soviet Union saw student politics as a proxy battleground for their rivalry.

In 1965, Paget and her husband attended a National Student Association seminar that was far more exclusive than the conference in Minnesota had been: only a dozen other students, sessions with experts on student politics in Africa and Latin America, and a visit to the State Department. When the seminar ended, the association offered Paget’s husband a job on its international staff in Washington. He was given a good salary, they were living in the nation’s capital, and at the next national conference of the group she got to sit on the dais while Vice President Hubert Humphrey gave a speech. “Our new life seemed almost magical,” she writes. But then one day Paget found herself alone with a man who “told me that my husband was ‘doing work of great importance to the United States government,’ and handed me a document to sign. . . . My host then revealed that he worked for the Central Intelligence Agency . . . and that he was my husband’s case officer.” The National Student Association, Paget discovered, was underwritten by the CIA.

Her husband had signed a similar document, a national-security oath. He had been, she writes, “deeply shaken by the revelation, which turned our time in Washington from a period of elation to one of confusion and, later, fear. . . . We told no one . . . we felt isolated.” The couple soon learned that revealing the association’s CIA ties would be a felony violation of the Espionage Act, and punishable by twenty years in prison. Suddenly they were in far over their heads; he was twenty-two, she was twenty, and they had a baby. What they had believed to be a democratically controlled student organization turned out to be something much darker. “We kept asking ourselves: How could this have happened?” Paget has spent many years working to answer that question, and the result is an important and carefully researched book about events that eerily foreshadow the Snowden era.

Paget has looked at what seems like every available written record, published and unpublished. The more than 150 people she interviewed include scores of former association officials, both witting and unwitting about the CIA relationship, as well as retired CIA men, some repentant and some defiant. The CIA was less than cooperative in response to her requests, and she found that it had reclassified documents that had been previously available to the public; her quest to get two reports from 1949, for example, took nine years.

Patriotic Betrayal is an impressive evening of the score by a woman who felt unfairly trapped and violated fifty years ago. It is not, I have to say, easy bedtime reading. A blizzard of names, initials, and acronyms sometimes overwhelms the reader. A glossary, timeline, and cast of characters all offer some help, though the snow remains thick. Still, Paget has done a true service by putting together a comprehensive history of the relationship between the CIA and the National Student Association, including much that has not been disclosed before. Her book offers a sobering lesson about what happens when a country loses control of its intelligence apparatus.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the National Student Association and student unions from other Western democracies belonged to the International Student Conference, a federation headquartered in the Netherlands, while student groups from the U.S.S.R. and its allies were members of a rival federation, the International Union of Students. The two organizations competed fiercely for the allegiance of students in nonaligned countries. But the I.S.C., like the National Student Association, was funded largely by the CIA, and huge amounts of agency money were covertly spent on its annual meetings and in support of its sixty-person secretariat. National Student Association officials traveled all over the world on the CIA’s dime to lobby student unions in other countries. They also arranged grants to establish student unions to the agency’s liking in countries that didn’t have them, and to create well-funded new unions to compete with those considered too far to the left. The CIA infiltrated nearly every level of the era’s student politics: in 1959, for example, it recruited Gloria Steinem, a recent Smith College graduate, to lead some one hundred Americans in disrupting proceedings and distributing pro-Western literature at a Soviet-sponsored youth festival in Vienna.

Patriotic Betrayal reminds us that the CIA’s control of the National Student Association gave it not just a means of influence but a fount of intelligence. Association staffers made “fact-finding” trips to other countries, where they interviewed student leaders at length and wrote reports; American and foreign student officials also took part in seminars on international issues, as Paget and her husband had. Over the course of six weeks, a seminar leader would encourage participants to freely voice their opinions, read what they wrote in essays, and could see who was friendly or unfriendly to American foreign policy. Hundreds of reports about the students taking part flowed back to CIA headquarters. The seminars were such an intelligence gold mine that the CIA replicated them throughout the world: thirty-three were staged in Africa alone. One report described a Congolese student as “the conservative, intelligent, French-speaking African people have been looking for.” A Cameroonian was rated well because he was “a genuine nationalist, though perhaps of the more revisionist moderate variety.”

The reports provided the CIA with information about the men and women who would someday be cabinet ministers, ambassadors, and U.N. officials. More ominously, they also gave the agency data to trade with other intelligence services. That is what all such agencies do. Many of the governments the United States was friendly with, however, were brutal dictatorships. The National Student Association was deeply involved, for example, in Iraq. In the early 1960s, the agency backed the Baath Party, which was seen as tough on communism. The association dutifully passed resolutions in favor of the Baathists, and its international staff supported a new Iraqi student union to counter the existing pro-Soviet organization. Once the Baathists took power in a coup, Paget notes, they arrested some 10,000 Iraqis, of whom they executed about half. Then a different Baathist faction seized power in a second coup and arrested students who had worked with the Americans. How many of the student victims in both groups were targeted via National Student Association reports that had been passed on to Iraq?

In Iran, the CIA had helped to put the shah on his throne and to establish his notoriously ruthless secret police. But at the same time, association officials — many of them unwitting about the CIA connection, and most of them liberals genuinely opposed to despotism — were helping an anti-shah union of Iranian students in the United States, all the while filing the usual plentiful reports about the union’s members. “My God,” a former association president burst out at an alumni gathering decades later. “Did we finger people for the shah?”

The tie between the CIA and the National Student Association was successfully kept secret for some twenty years. Students recruited for the group’s international staff, or those who were urged to run for its key elective offices, were carefully vetted by veterans of the organization who had the CIA’s interests in mind. Once in place, and likely pleased to have an exciting job with the chance to travel, a new association official would be told that he (it was almost always a he) was about to be given some highly confidential information. Who will turn down the chance to hear a secret — and who won’t promise, in return, to keep it?

Given the CIA’s vast budget, money was never a problem for the association: once a project had been approved by Langley, the financial spigot gushed in response to a mere one- or two-page funding proposal. A sum worth more than a million dollars in today’s money was spent organizing a single conference in Ceylon in 1956. A decade later, the CIA was spending twenty times that much on student operations each year. In case skeptics were to ask questions about the lavish funding for sch programs or the association’s comfortable double-town-house headquarters near Dupont Circle — were there no strings attached to any of these plentiful foundation grants? — there was a handpicked advisory board that could be counted on to say that all was on the level. But then, suddenly, everything came unglued.

In early 1967, a frightened, bushy-haired man named Michael Wood approached Ramparts magazine with a story so far-fetched that at first no one believed him. Wood had been hired as the National Student Association’s fund-raiser. Like anyone in such a role, he knew that an organization’s most promising source of donations was those who had already given. But he was baffled when he was told not to contact several of the foundations that had been the association’s most generous supporters, such as the innocuously named Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs. He repeatedly protested to the friend who had hired him, National Student Association president Philip Sherburne, and eventually Sherburne sat him down for a confidential talk. After having been elected, Sherburne said, he had been horrified to learn that most of the money was coming from the CIA. He had brought in Wood to raise funds from other sources so that this embarrassing connection could be ended for good.

Achieving that goal turned out to be far more difficult than either man imagined. The CIA, alarmed at the prospect of losing its hold over the student union, began playing hardball. The Foundation for Youth and Student Affairs abruptly claimed that the National Student Association owed it large amounts of money. A number of staff members, including Sherburne himself, had their CIA-arranged draft deferments canceled — a lethal threat during the escalation of the Vietnam War. And when the CIA learned that Sherburne had violated his national-security oath by talking to Wood, the agency became nastier still. Fearful of a possible prison term, Sherburne sought legal advice from Roger Fisher, a distinguished Harvard Law School professor. Soon after, a senior CIA official appeared at Fisher’s office and asked him to drop his client. When Fisher refused, the man hinted that there could be unfortunate consequences for Fisher’s brother, a foreign-aid official stationed in Colombia. Fisher, to his credit, was not swayed.

Frustrated, Wood went to Ramparts, which had established itself as a saucy journal of investigative reporting and was known for a damaging exposé it had published of the CIA’s involvement in a Michigan State University aid program in Vietnam. The magazine’s editors were initially skeptical of Wood’s tale, but the story soon checked out. When Michael Ansara, a Ramparts researcher in Boston, began to investigate the foundations that had funded the National Student Association, he discovered that most were housed in law firms, where attorneys refused to talk about their clients. Ansara then consulted a legal directory and realized that the law firms all had something in common: each had at least one senior partner who, during the Second World War, had served in the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of the CIA.

At the time I was a young staff writer at the head office of Ramparts, in San Francisco. I worked on the story in a small way, rewriting a short section of it and traveling to interview a former association officer who, unsurprisingly, denied everything. It soon became clear that the CIA knew what we were up to, and the magazine took all sorts of frantic precautions: we made furtive calls from pay phones, and hired a bored-looking Pinkerton guard to sit by the front desk. Wood came and went from the office, and one evening when he and I and several others were working late, we were frightened by a string of loud explosions in the street outside. Was this how it was all going to end? But there was no CIA assault team. The office was on the edge of Chinatown, and we had forgotten that it was the Chinese New Year.

In mid-February 1967, we got word that the National Student Association was about to call a press conference and intended to put its own spin on the story before we were ready to publish. What could be done? The issue of Ramparts with the exposé wasn’t yet at the printer’s. Warren Hinckle, the magazine’s editor, had the brilliant idea of placing a full-page advertisement announcing the story in the next morning’s New York Times and Washington Post. The association was upstaged, the story and its reverberations were on newspaper front pages for a week, and a group of members of Congress signed a protest letter that was sent to the president. This began a long period of public embarrassment for the CIA, which climaxed in the 1970s with the revelation that it had attempted to assassinate foreign leaders.

In the wake of the Ramparts story, something happened that none of us had anticipated. Reporters began to look at public records to see what other organizations the CIA’s conduit foundations had funded. Hundreds were discovered: the Congress for Cultural Freedom, labor and church groups, journalists’ organizations, and more. But none had been more important to the CIA than the National Student Association, which gave the agency influence over national and international student politics at a time when it was eager to battle the Soviets on every possible front.

After the exposé, some CIA defenders argued that it had been a good thing to create a democratically oriented international student federation as an alternative to the Communist I.U.S. Paget adds a curious fillip to the argument, which should be a warning to any regime that thinks it can secretly pull the strings of a front organization forever. The I.U.S. was based in Prague, and many of its top officials were Czechs. But surprisingly, the group’s three most important leaders became major figures in the Prague Spring of 1968, which was crushed by Warsaw Pact troops. The Prague Spring started less than a year after the Ramparts story broke. It’s a pleasure to imagine spymasters in Moscow and Langley pounding their desks at almost exactly the same time, in anger at the young people who had escaped their control.

And pound their desks they certainly did. When President Lyndon B. Johnson heard about the impending Ramparts story, he summoned CIA chief Richard Helms back to Washington from a trip to the nuclear labs at Los Alamos. The CIA, in turn, called home some 200 agents from overseas to discuss damage control. The agency quickly persuaded some friendly members of Congress to declare that they had known and approved of the relationship with the National Student Association (not true), and twelve former association presidents signed a statement that the CIA had never interfered with their activities (also a lie — the CIA had directed much of what they did). Paget dryly notes that three of the statement’s signers were CIA career agents at the time; all but one had continued to work for the agency after his term as president expired.

Many people felt shocked and betrayed to learn of the close connection between the two organizations. Shortly after the tie was revealed, I met a former South African student leader, a passionate anti-apartheid activist. He was trying to gather support overseas for an underground resistance movement, and thought he had a sympathetic ear in an American friend who had been an official of both the National Student Association and the International Student Conference secretariat. The two had been so close that one had been the best man at the other’s wedding. Now, stunned by the Ramparts article and the revelation that the American had been aware of the CIA tie, the South African was agonized, wondering how much of what he had confided to his former friend had made its way back to Pretoria.

He was right to wonder, for we know now that despite its public denunciations of apartheid, the U.S. intelligence establishment shared a huge amount of data with South Africa for decades. This included satellite intercepts of African National Congress radio communications as well as the information, passed on by a CIA officer in Durban in 1962, that allowed the South African police to put their roadblock at the right place to arrest Nelson Mandela, the event that began his twenty-seven years in custody.

The CIA clearly knew that the revelation of its control of the National Student Association could have reverberations around the world and might unravel its whole web of covertly funded organizations. It reacted with alarm to the news that Ramparts was working on the story, establishing a “Ramparts Task Force” at Langley and gathering information on many of us who worked at the magazine. It was chilling to discover how closely the agency was watching Ramparts and its employees. A decade after the exposé, under the Freedom of Information Act, I was able to get redacted copies of the CIA’s files on me — a dossier of more than a hundred pages, even though I was a very low man on the Ramparts totem pole. Although I was pleased to be referred to as “a needle to the Agency,” various garbled details do not inspire faith in the CIA’s concern for accuracy. One example: My wife and I were married soon after having been civil rights workers in Mississippi, and in lieu of wedding presents, we asked people to make donations to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In a report by a CIA agent whose name had been redacted, this was recorded as “gave his wedding presents to Goodwill.”

Do democratic governments have the right to gather intelligence, and to gather it secretly? Of course: we live in a world with malicious regimes and movements. But intelligence gathering can all too easily expand into realms that have nothing to do with thwarting possible attacks — whether that means passing on information about student leaders to repressive regimes, or tapping Angela Merkel’s cell phone, or vacuuming up the emails and text messages of hundreds of millions of people at home and abroad while the highest intelligence officials deny to Congress that any such thing is happening. The news of the CIA’s control of the National Student Association, Paget tells us, came as a complete shock to as high an official as Vice President Humphrey.

The more clandestine intelligence operations are, the more we need rigorous vigilance to ensure that the ends do not corrupt the means. Otherwise we start to look like our enemies: to combat a Soviet front organization, we create a front organization of our own; to build allegiances against secret-police regimes, we finger people for the shah’s secret police; to fight the brutality of Al Qaeda, we brutally torture prisoners. The power whose abuse Edward Snowden alerted us to is essentially electronic; the power that the CIA wielded through the National Student Association was financial. In neither case were there checks or balances. Both scandals warn us of what can happen when great power is exercised without oversight or conscience.