Discussed in this essay:

A Big Enough Lie, by Eric Bennett. Triquarterly. 296 pages. $17.95.

The Yellow Birds, by Kevin Powers. Back Bay Books. 256 pages. $14.99.

Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, edited by Matt Gallagher and Roy Scranton. Da Capo Press. 256 pages. $15.99.

Redeployment, by Phil Klay. Penguin Books. 304 pages. $16.

Fives and Twenty-Fives, by Michael Pitre. Bloomsbury. 400 pages. $17.

The Watch, by Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya. Hogarth. 318 pages. $15.

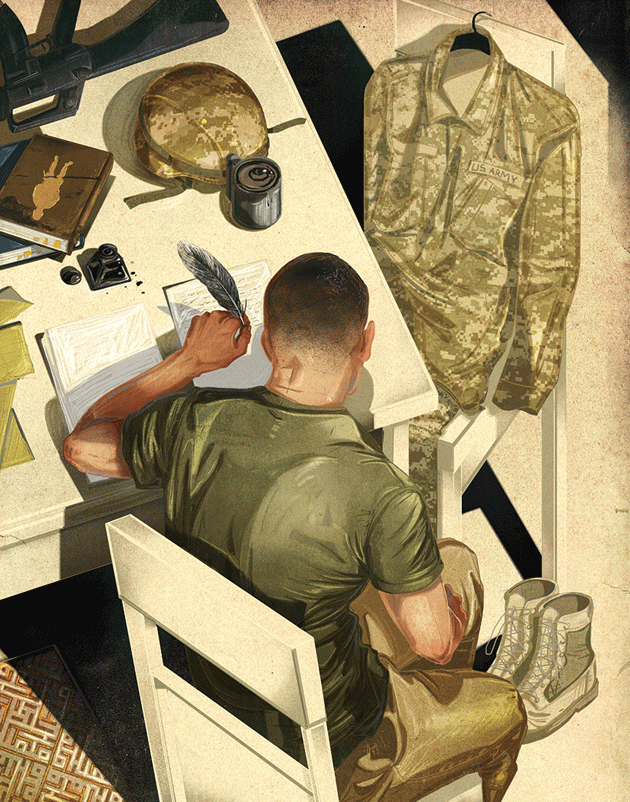

Toward the end of 2012, when the first major fiction by veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan began to be published, the response from the literary world fell somewhere between celebration and relief. The books seemed to herald a sorely needed reckoning. After years of awkward silence, here, finally, were writers willing to urge a complacent and distractible public to confront the tragedies of the Terror Wars.

Critics and commentators who sensed the importance of this transformation were keen to enlist these veterans into the ranks of classic war writers. The 2014 National Book Award citation for Redeployment, Phil Klay’s story collection, argued that “if all wars ultimately find their own Homer, this brutal, piercing, sometimes darkly funny collection stakes Klay’s claim for consideration as the quintessential storyteller of America’s Iraq conflict.” In an appreciation of Klay and others, including Michael Pitre, the author of the novel Fives and Twenty-Fives, and Kevin Powers, who won the 2013 PEN/Hemingway award for The Yellow Birds, Michiko Kakutani wrote in the New York Times:

All war literature, across the centuries, bears witness to certain eternal truths: the death and chaos encountered, minute by minute; the bonds of love and loyalty among soldiers; the bad dreams and worse anxieties that afflict many of those lucky enough to return home. And today’s emerging literature . . . both reverberates with those timeless experiences and is imprinted with the particularities of the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In The New Yorker, George Packer also saw continuity between this crop of young veteran authors and their forebears, but he emphasized something different: the healing role that fiction can play after the fighting is over. Calling to mind Vietnam veteran Tim O’Brien’s assertion that “stories can save us,” Packer pointed to the feeling of communion that these books can inspire: “Some will begin to recognize their own suffering in the stories of others. That’s what literature does.”

Modern war writing is a strange thing to praise, because such praise ennobles the account while deploring the event. Time and distance blunt this quandary — most of us, if we are honest, are happy that there were battles at Agincourt and Borodino because of the literature they inspired — but when the dead are barely cold, it’s necessary to keep two sets of books. This is why a familiar language of acclaim is always invoked: shared suffering, eternal truths, the passion play that transmutes pain into collective redemption. War is hell, but its themes make critics purr.

This division awkwardly mirrors the distant, unreal nature that today’s conflicts have for most American civilians. The public’s unprecedented disconnection from the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan — wars waged by a volunteer army and funded with borrowed money — has made it all the more eager to genuflect before the writing that has emerged from these conflicts. As if in response to this public appetite for artistic redemption, veterans have been producing stories of personal struggle that are built around abstract universal truths, stories that strive to close the gap between soldier and civilian. As Private Bartle, the traumatized narrator of The Yellow Birds, says: “Nothing is more isolating than having a particular history. At least that’s what I thought. Now I know: All pain is the same. Only the details are different.”

All pain may be the same, but all wars are not, and in the search for reconciliation that distinction has gone missing. Why did we fight these wars, and what were we trying to achieve? Did we succeed or did we fail? What consequences have we wrought on the countries we attacked? What, if anything, have we learned? Questions like these rarely come up in recent war fiction, because they lie outside the scope of personal redemption, beyond the veteran’s expected journey from trauma to recovery. As one of Klay’s narrators puts it:

The weird thing with being a veteran, at least for me, is that you do feel better than most people. You risked your life for something bigger than yourself. How many people can say that? You chose to serve. Maybe you didn’t understand American foreign policy or why we were at war. Maybe you never will. But it doesn’t matter.

To be sure, Klay is not presenting this attitude without irony, but it’s representative of a genre that scrupulously avoids placing the Terror Wars within a larger political or ideological context. Redemption seems to rely on a shared incomprehension of what exactly these wars were about. Stories can save us, as O’Brien said, but they can also let us off the hook.

The working template for the contemporary soldier’s story was set almost immediately with The Yellow Birds. Fire and Forget, a 2012 anthology of short stories by returning veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan, appeared soon after. In his introduction, Colum McCann writes that the authors’ words “eclipse war” and “bring back the very humanity we have always desired.” The power of these stories, he suggests, comes from the way in which they transcend their contexts. It’s striking that fewer than half the stories in Fire and Forget, which was edited by Iraq veterans Roy Scranton and Matt Gallagher, are about the fighting itself; most concern characters coping with post-traumatic stress or struggling to reacclimate to civilian life. In The Yellow Birds, Bartle returns home isolated and suicidal, ashamed “on a cellular level” by what he has seen and done in Iraq.

The stories also share a consistent perspective. They view the war from the restricted point of view of individual characters, to whom no larger picture of the conflict is visible. The narrator of Jacob Siegel’s “Smile, There Are I.E.D.’s Everywhere,” which opens Fire and Forget, explains,

For us, there had been no fields of battle to frame the enemy. There was no chance to throw yourself against another man and fight for life. Our shocks of battle came on the road, brief, dark, and anonymous. We were always on the road and it could always explode. There was no enemy: we had only each other to hate.

The Yellow Birds turns on the desertion and death of Bartle’s closest friend, but the scenes set in Iraq are curiously ethereal. Powers, a former Army combat engineer, has also written poetry, and he seems torn between indirect, lyrical evocations of the war zone — a desert firefight is “hazy and without sound, as if it was happening underwater” — and raw, confessional outpourings about Bartle’s feelings of blame and despair.

In his author’s note in the paperback edition, Powers writes that his intention was “to create a cartography of one man’s consciousness.” The same could be said of almost all contemporary war fiction: to hear these books tell it, the soldier’s consciousness is the field of battle. You find the same close focus throughout the lengthening list of fiction by veterans: Fives and Twenty-Fives; The Knife, by Ross Ritchell; War of the Encyclopaedists, which was co-written by Gavin Kovite and Christopher Robinson; and, most recently, I’d Walk with My Friends If I Could Find Them, by Jesse Goolsby. (That these books are all by men shows how traditional the veteran’s narrative remains. There are more than 200,000 women on active duty in the military, but the female experience of warfare has barely been broached.)

The first-person narrators in Phil Klay’s well-crafted Redeployment share this self-involvement. The running theme of the book is uncertainty, both in the nature of combat and in the stories that people tell about it. Klay, a Marine Corps veteran, occasionally widens his lens to examine the cruelty and dysfunction of the war at large. “Ten Kliks South” reveals the workings of an artillery unit whose target areas are more than six miles away, and who therefore have little idea how many people they’ve killed or who those people are: “Wherever we hit, everything within a hundred yards, everything within a circle with a radius as long as a football field, everything died.” The follies of nation-building are exposed in the Helleresque “Money as a Weapons System,” which is set within the compound of an incompetently run Provincial Reconstruction Team.

Ultimately, however, Redeployment returns to the confined viewpoints of individual soldiers who can’t comprehend what they’ve experienced. “You can’t describe it to someone who wasn’t there, you can hardly remember how it was yourself because it makes so little sense,” says one of Klay’s characters. This sort of anxious metafictional meditation seems to have become almost compulsory for contemporary chroniclers of war. Here is Siegel:

I got up every day after Annie went to work and tried to make sense of what happened over there, how it all fit together, why it counted for so much if I wasn’t even sure how to add it up. . . . I couldn’t write the things that haunted me for fear of dishonesty and cheap manipulation, which I blamed on not being haunted enough.

Pitre:

It’s not smart for me to tell stories. Makes people uncomfortable. . . . Even the memories that seem funny in my head come out sounding like the summer vacation of a psychopath.

Powers:

What happened? What fucking happened? That’s not even the question, I thought. How is that the question? How do you answer the unanswerable? To say what happened, the mere facts, the disposition of events in time, would come to seem like a kind of treachery.

Why are so many veterans telling the same kind of war story? The authors of these books share something else besides military service. The editors of Fire and Forget met in NYU’s Veterans Writing Workshop. Michael Pitre studied creative writing as an undergraduate. Kevin Powers, Ross Ritchell, Jesse Goolsby, and Phil Klay are all M.F.A. graduates. (The authors of War of the Encyclopaedists split the difference: Gavin Kovite is a former infantry-platoon leader; Christopher Robinson has the fiction degree.) Nearly all recent war writing has been cultivated in the hothouse of creative-writing programs. No wonder so much of it looks alike.

This, at least, is the suggestion that Eric Bennett makes in his new novel A Big Enough Lie, the first satirical treatment of contemporary war fiction and the classroom politics that produce it. Bennett is himself a graduate of the oldest and most revered of these programs, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and he earned a Ph.D. studying the history of writing programs after World War II. His articles and the forthcoming monograph built from them, Workshops of Empire, make for a fascinating complement to his novel. As with most polemics against M.F.A. culture, they carry a whiff of personal grievance that helps animate the critique.

Bennett’s account goes like this. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop began in 1936, but it wasn’t until the end of World War II that it and a few other programs rose to prominence. The G.I. Bill flooded universities with repatriated soldiers, and many of the earliest workshop enrollees were veterans. Several programs had a distinctly military feel. Iowa’s classes were held in Quonset huts along the Iowa River. Wallace Stegner, who founded Stanford’s writing program in 1946, sought to replicate the camaraderie of an Army squadron, and he hoped to apply his students’ military discipline to the craft of writing.

But what did this craft entail? Bennett contends that the guiding force behind the “workshop method” that we know today was Paul Engle, the Cold Warrior poet and administrator who directed Iowa’s writing program between 1941 and 1965. Engle had a keen business sense — he attracted the support of wealthy donors like the Rockefeller Foundation by convincing them that the writers’ workshop was a significant staging ground in the culture wars against fascism and Communism. The program, he argued, would foster literature that opposed demagoguery and collectivism and celebrated individuality and self-expression — “the singular, the personal, the anomalous, and the particular,” as Bennett puts it.

Ernest Hemingway was Engle’s paradigm. Bennett cites a 1929 letter by the poet Allen Tate that, in praising Hemingway, extolled precisely the qualities that Engle hoped would define the discipline of creative writing:

Whether or not you like the kind of people he has had to observe, the very fact that he sticks to concrete experience, to a sense of the pure present, is of immense significance to us. Hemingway, in fact, has that sense of a stable world, of a total sufficiency of character, which we miss in modern life.

Hemingway’s fiction was grounded in the immediate perceptions of his characters. It was anti-institutional, and subordinated broad ideas to finely described moments. Engle’s workshop pedagogy therefore elevated small, glistening gems of subjective experience over sprawling, panoptic structures such as John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy and Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. As Bennett writes, “Universities privileged the particular over the universal, the sensory over the ideational, the concrete over the abstract.”

Whatever the political origins of the modern writing program — Bennett traces funding from the State Department and the CIA — the aesthetic he describes is spot-on. Engle’s preferred style found confirmation in Writing Fiction (1962), an influential student handbook by R. V. Cassill, a onetime Iowa professor and the founder of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs. The self, Cassill said, remained the first and best source for a writer’s material:

As soon as we have learned something about our craft we are tempted to turn from concentration on our own experience to the public world of great events — to write about spies and congressmen. But the first commandment is to go back stubbornly to our own fields.

From such an ethos emerge the well-worn axioms of the creative-writing program: “Find your voice.” “Write what you know.” This pluralism remains foundational to the workshop philosophy, which produces writers dedicated to exploring their own personal stories. These tend to be rooted in identity — social class, ethnicity, a defining childhood crisis, or anything else from an author’s background that seems to set them apart. For veterans, military service unquestionably constitutes that distinguishing characteristic.

Tim O’Brien is by far the most important of the type. His debut novel, Northern Lights, from 1975, is a pastiche of The Sun Also Rises, but in later work O’Brien applied Hemingway’s precision and concreteness to the psyche, making explicit the thoughts and emotions that Hemingway had left implied. Along with the physical objects enumerated in “The Things They Carried,” the best-known story to come from the Vietnam War, O’Brien’s soldiers shoulder their hopes, their fears, their guilt, and their remorse. This expanded sense of interiority was partly a response to the abstract nature of combat in Vietnam. O’Brien has said that he encountered the Vietcong only once during his tour of duty: “All I saw were flashes from the foliage and the results, the bodies.” With the forms of battle now faceless and remote — sniper fire, booby traps, air strikes — and the intentions of the war either forgotten or discredited, O’Brien burrowed inward to locate the bedrock of the real. His descriptions of the Vietnamese jungle frequently blend together with his soldiers’ dreams and fantasies, and he seems less interested in the specifics of the fighting than in the catharsis of the telling. His much-anthologized “How to Tell a True War Story” is regarded as both a sensitive and self-aware classic of war fiction and a useful tool for writing instruction.

In developing his technique, O’Brien also carved out a niche. In The Program Era (2009), a shrewd and acerbic study of postwar fiction, Mark McGurl suggests that war writers had become a distinct “minority culture” by the time of Vietnam. O’Brien, he writes, is a “Veteran-American writer, in the sense that the psychic wounds inflicted on him in his year of combat have become foundational to a career in the same way that [Philip] Roth’s Jewishness has.” The demotion of war writing to a discrete subgenre reflected the increasingly remote role the military had come to play in most people’s lives. But McGurl suggests that the tendency to define writers by their identities had another ironic and insidious effect — it prompted greater homogenization. Although the subjects of program writing were superficially diverse, the narratives became ever more uniform. Story after story concerned an individual’s attempts to overcome adversity, to pass through the pain and isolation of his circumstances and arrive at some universal understanding. For a time, focusing on “biographical singularity” was a way to rebel against institutions like the military or the middle class, Bennett writes. “But what happens to the rebel if everyone follows him?”

Bennett’s A Big Enough Lie is a disgruntled send-up of exactly this kind of identity politics. It focuses, of course, on a would-be writer, John Townley, whose artistic and romantic ambitions lead him into a bizarre masquerade. As a student in a fictionalized version of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he pretends to be a disabled Iraq War veteran. To fill out this persona he purloins the stories of a childhood friend who fought in the army. More audaciously, he borrows details from the life of an American soldier who is presumed dead after a nationally reported kidnapping in Babylon. The shocking memoir Townley fabricates — its chapters intersperse Bennett’s narrative — is championed by an Oprah-like talk-show host, who transforms him into a celebrity and makes it all the more probable that he’ll be exposed as a fraud.

There’s a clever two-way game going on here. On the one hand, Bennett gets to smuggle his own first-person war narrative into publication, despite his lack of military credentials. On the other, he is able to assail the fetishization of authenticity among publishers and readers, and the patronizing celebration of books that conform to our preconceived expectations about suffering and heroism. Throughout the novel, Townley expresses a frustrated yearning for a literature that offers more than a confirmation of lived experience — he wants conceptual or philosophical or visionary fictions that can access something other than received opinions. “What if there are truths we can absorb only through hypothesis and imagination?” he thinks. “What if there are powers of sympathy exercised only by exposure to the untrue?”

“A novelist is an artist, and an artist is somebody with a certain relationship to the world, an imaginative one, a subversive one. A clever one,” says another of Bennett’s characters. “He plays hypothetical pranks and has all the freedom in the world to do so.” Bubbling throughout A Big Enough Lie is an exhortation to reconsider the qualities we have been trained to value in literature. What if invention and exploration were more esteemed than testimonies of personal struggle? What might the novel be capable of — aesthetically and politically — if it broke out of its obsessively curated pigeonholes of first-person experience?

Yet Bennett, too, struggles to escape the hall of mirrors that turns every novel into a study of itself — this is, after all, a book about someone frustrated with M.F.A. programs written by someone frustrated with M.F.A. programs. The workshop doctrine of self-expression is hard to shake off.

If veterans played a crucial part in the origins of the writers’ workshop, the workshop has since returned the favor. Dozens of programs created specifically for veterans, like the one at New York University where many of the contributors to Fire and Forget first met, have emerged in recent years. Many veterans have reported finding the workshops more helpful and inviting than the group-therapy sessions provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs. In an age when the isolation of returning soldiers is more pronounced than at any time in American history, it’s proved to be an effective, and necessary, service.

There is an important distinction between writing for yourself and writing for the public. Yet the difference between private, therapeutic writing by recovering veterans and the recent spate of published war fiction often feels like one of degree rather than of kind. Individually the depictions of war presented by these latter books can be moving, but their cumulative effect has been to create a pitiable image of American soldiers that generates a condescending kind of sympathy but rarely any respect: bewildered, ineffectual, cynical, destructive, incapable of distinguishing between civilians and the enemy, and intensely preoccupied with their own sense of victimhood. In the most plaintive of Phil Klay’s short stories, “Prayer in the Furnace,” a company chaplain is approached by a Marine who shows him a photograph of a small Iraqi child setting down a box:

“That kid’s planting an I.E.D.,” he said. “Caught in the fucking act. We blew it in place right after the kid left, because even Staff Sergeant Haupert didn’t want to round up a kid.”

“That boy can’t be older than five or six,” I said. “He couldn’t know what he was doing.”

“And that makes a difference to me?” he said. “I never know what I’m doing. Why we’re going out. What the point of it is. This photo, this was early on when I took this. Now, I’d have shot that fucking kid. I’m mad I didn’t.”

The equivalence between American soldiers and helpless children runs throughout contemporary war fiction. But whether or not it’s an accurate depiction, the narrative possibilities offered by the analogy are extremely confining. If a soldier kills a non-combatant — an event that occurs in many of these books — the story rarely explores the larger meanings and ramifications of that act. The emphasis inevitably narrows to the soldier’s ability to come to terms with his pain.

There are signs that veterans themselves are growing frustrated by these conventions. In an essay published this January in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Roy Scranton, one of the editors of Fire and Forget, threw a few sharp elbows at fiction that colluded in what he called the “myth of the trauma hero,” a story arc that traced an idealized soldier’s journey from innocence to trauma to recovery. Writers, he argued, had become attuned to the myth’s marketability and sometimes seemed “eager to capitalize on the moral authority it offers.”

The workshop model, with its reverence for small, human moments of inner transformation, doesn’t allow for many other storytelling options. “Write what you know” is a difficult mantra when you know so little. In a prescient essay from 1973, Alfred Kazin asked the question that continues to bedevil war literature:

But what to do when individuals at war are no longer interesting, when the only real protagonist at war is the nation-state, the war-state, the war-leaders . . . ? The contemporary novel, haunted by the power of impersonal structures, still has no practice in employing wholly impersonal characters. General Westmoreland, no doubt in disgust with American troops, anticipates a time when war will be completely automated.

The automated war is nearly upon us, and it threatens to make the fiction writer’s classroom lexicon anachronistic. Today, Hemingway’s “pure present” is mediated by technology. “Concrete things,” which to Wallace Stegner were the alpha and omega of human truth, have been replaced by virtual images. When enemies are seen at all, it is through night-vision goggles or computer screens that make them look like video-game avatars. Drones do most of the killing, but drones don’t write confessional, first-person novels to tell us what it’s like.

Fortunately, the novel is an adaptable art form. Attending to the singular and the personal — to what Henry James called the “present palpable intimate” — is only one of the things it can do well. It can also place individuals within larger structures of meaning and operate from impersonal, godlike distances. It can create earthy social networks, as in the work of Dos Passos, Mailer, and Elsa Morante. It can unspool philosophical theses, as in Tolstoy and Vasily Grossman. It can be political, allegorical, panoramic, kaleidoscopic, and epic. Contra R. V. Cassill, it can even be about spies and congressmen — spies and congressmen being an integral part of the world.

One obvious route out of the cul-de-sac of personal experience is to inhabit the perspectives of America’s enemies or allies. The liveliest writing in Pitre’s Fives and Twenty-Fives comes in the sections devoted to an Iraqi interpreter, whose ambivalent and somewhat bemused relationship with the U.S. infantrymen casts the American misadventure in a sardonic light. In Green on Blue, Elliot Ackerman, a former Marine Corps Special Operations team leader, chose to concentrate almost entirely on the Afghans with whom he served. The novel is about an Afghan soldier who joins an American-funded army division in order to avenge his brother, who was wounded in a Taliban bombing. The plot allows Ackerman to frame the nebulous global war on terror as a local conflict defined by the tension between family and community loyalties.

Long-proscribed concepts like loyalty, honor, and courage reemerge in the Indian-born writer Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya’s The Watch, which reprises the story of Antigone at an American military outpost in Afghanistan. Roy-Bhattacharya did not fight in the war, and he grants himself powers of omniscience that many veterans seem reluctant to claim, moving confidently between the points of view of American soldiers, local Afghans, and a Northern Alliance translator. The author’s deft manipulation of a large dramatis personae reinforces the sense of classical tragedy and stops the novel from being sucked toward the abyss of subjectivity.

Without this sort of complex and imaginative approach to the experience of war, American fiction is in danger of settling into the patterns of complacency that smoothed the path to the Terror Wars in the first place. The publishing status quo, which rewards soldiers who chronicle their pain with book prizes and extravagant blurbs, bears an unsettling resemblance to a volunteer army that allows the public and the intellectual classes to outsource their accountability and guilt. Proclaiming that veteran authors have transformed war into Homeric masterpieces filled with timeless truths is a way of excusing our own indifference. Extolling literature for its healing properties after a period of national trauma looks a lot like congratulating ourselves for having gotten through a bad time with minimal unpleasantness. Meanwhile, the relationship between the public and the military is more remote than ever, and our memory of the reasons we launched wars against Afghanistan and Iraq has grown correspondingly thin. One of the jobs of literature is to wake us from stupor. But in matters of war, our sleep is deep, and the best attempts of today’s veterans have done little to disturb it.