This is how you get a cow to stand still: round up the herd, then urge them into a chute. Some chutes begin as wood, but all end as metal, with what is called a headgate. Today’s chute, in north-central Iowa, is inside a large barn, which protects against the November chill. In single file, the cattle pass through the chute, whose far end faces open doors. As each cow nears daylight and seeming freedom, the farmer pulls a lever to close the headgate, leaving the cow’s head poking out the end of the chute and her body immobilized inside. A veterinarian named Renee Bertram administers injections in the muscle around the left shoulder. Her boss, Zach Vosburg, meanwhile steps into the chute behind the cow, his right arm encased up to the shoulder in a latex glove. He has just applied lube, and as a farmhand lifts the cow’s tail, the thirty-four-year-old vet slides his fingers into the animal’s rectum.

“Come on, darlin’, let me in.”

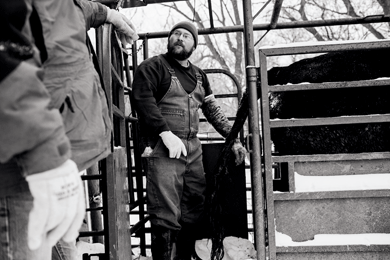

Photographs and border photographic details from Franklin County, Iowa, February and June 2015, by Lance Rosenfield. All images © Lance Rosenfield/Prime This page: Cattle at a farm in winter

The cow hardly flinches. Vosburg gazes into space as he feels around inside: he’s hoping to discern the shape of a calf’s head through the walls of the intestine and the uterus. All human eyes are on him, awaiting the verdict.

“She’s bred,” he finally declares. “Nice big calf in her.” A pause. “Four and a half, five months.” Vosburg has an educated hand, can judge the age of a fetus by the size and position of the head.

On his clipboard, the farmer notes the good news and the number on the cow’s ear tag. Vosburg withdraws his manure-stained arm. The farmer opens the headgate and the cow bounds out. Next!

A couple of months earlier, in August of last year, things had been slow. The Hampton Veterinary Center, which Vosburg bought in 2012 with his wife, Alexis, is a mixed-animal practice. “Anything can walk through that door,” as he puts it, and household pets come through it all year round. (Farm animals actually enter the clinic through large overhead doors in the back.) But a surge of farm work begins in the fall, when cattle need vaccinating and preg checking, and continues through the spring, when cows calve, horses foal, and goats kid.

Vosburg has two full-time and five part-time employees, all of whom need to be paid whether the work is there or not. Their presence imparts a healthy bustle to the clinic — yet the business of being a country veterinarian is increasingly precarious. The heartland has been emptying of large-animal vets for at least two decades, as agribusiness changed the employment picture and people left the region. Many vets simply close shop when they retire; private practice is too hard a way to make a living. Meanwhile, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service has become the nation’s largest single employer of vets, most of whom work in meat and poultry plants, where they oversee not animal husbandry but slaughter.

Today’s vet-school grads, about 80 percent of them women, head overwhelmingly to jobs in cities and suburbs, to work with pets. The reasons are easy to understand. For one thing, their fees aren’t tied to the market value of the animal; people spend more on critters that share their homes. With food animals, a farmer’s decision to summon the vet necessarily involves a calculation of profit and loss. In addition, the hours are better for an urban vet. A large-animal practitioner is usually on call twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week — and typical days involve a lot of highway driving. Maggie Hess, who is Vosburg’s office manager, told me that her boss was one of a vanishing breed. “There aren’t so many left. They become afraid of getting hurt. Or waiting forty days on their money.”

Waiting for clients to pay their bills is only one part of the squeeze. In 2012, when Vosburg was working for Richard Flickinger, the previous owner of the clinic, a Des Moines bank strung him and Alexis along for months as they prepared to buy the business. (Their application was denied at the eleventh hour; a bank in Hampton ended up extending the necessary credit.) Husband and wife also had student loans and, in Zach’s case, almost $100,000 of debt from veterinary school at Iowa State. They gained some relief in 2013, when he won an award of $75,000 from the USDA’s Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program. Under the program, the government pays off $25,000 of debt each year for three years if a practitioner relocates or extends his practice to an underserved area. To meet these guidelines, Vosburg agreed to serve the residents of Butler County, just east of Franklin County, where his clinic is located.

He was, in other words, sticking close to home. Vosburg guesses that only a handful of the 103 members of his graduating class at Hampton-Dumont High School got four-year degrees and then returned to the small town of 4,400. Right out of Iowa State, in fact, Vosburg had landed a job at a prestigious horse clinic in Utah. The place was flush, he recalls, spending more than his annual salary on maintenance fees for its digital radiology machine. Leaving was a tough decision, on many counts. It meant sacrificing not only a lucrative career track but prestige: in his profession, changing your focus from horses to cows is like working on buses instead of BMWs. But after a little more than a year, he and Alexis headed home to Hampton. There his parents live a quick drive away, on their own farm, and both his sister’s family and Alexis’s are also close at hand.

“I wanted my kids to be able to know their grandparents the way that I knew mine,” says Vosburg. But he also takes great pleasure in being part of “the two percent” — the sliver of the U.S. population that lives outside cities and produces the food that everyone eats. The personal, professional, and regional impulses are inseparable, and Vosburg manages to combine the heartland pride of John Mellencamp with the rural house-call ethos of the veterinarian-memoirist James Herriot. He is well aware that caring for all creatures great and small places him in a marginal position. Still, by “working smarter” and following his motto, Semper Gumby — “Always be flexible” — he hopes to succeed as a newfangled old-fashioned vet.

Vosburg’s unprepossessing clinic sits on the main road connecting Hampton to Interstate 35, which in turn connects Minneapolis to Des Moines. Town is a mile and a half away; corn is all around, sprouting from Iowa’s famous dark soil. When clients and patients enter the waiting room, you can often hear them from the big shared office, which is adjacent. Some of the clinic’s longtime clients, typically farmers who have known Vosburg for years, drift into the office through the open door, chatting everybody up, checking out the plate of brownies a staffer brought in, or leaving a gift of a dozen eggs or a sack of potatoes. “How’s the harem?” a farmer might shout at Vosburg, who smiles back: he’s the only man on staff. The office cat, Muggles, has a cushion next to a computer and seems to enjoy the music piping quietly from the speaker. (“She likes Enya,” says Jolyne Edwards, the inventory manager.)

A Monday morning in September of last year brought some problems that had materialized over the weekend. There was an overweight golden retriever that had been throwing up (diagnosis: probably too many snacks), a pit bull that had run into a barbed-wire snare in the woods and had gashes around its neck and shoulders, and a homeless kitten with an open wound on its tail that was infested with maggots.

Veterinary medical instruments, pens, blood-collection tubes, a utility knife, and a winter hat and gloves in the console of Vosburg’s pickup truck

Renee Bertram and another young vet, Krystal Ranes, deal with these cases while Vosburg fields calls from farmers who want him to stop by and attend to a pony with a sore hoof, a ram with an infected scrotum, and a cow that died unexpectedly. He listens to their problems, restates them in his own words, offers some thoughts about what might be happening, and then summarizes. He never hurries, and he spends a lot of time listening — some of the calls are long ones. A ringing telephone is the sound of a healthy practice; after the slowness of summer, it is reassuring. Vosburg explains that early fall in Iowa is “combine season,” with farmers working around the clock to get their crops in. As autumn progressed, though, more and more calls would come in for big “chute jobs” — vaccinating, castrating, even preg checking entire herds of up to a hundred cattle — which might take many hours and require more than one veterinarian.

“The day the first call for a chute job came in?” says Bertram, referring to a gig in late August. “Zach was so happy, he was singing and dancing.”

Vosburg is planning to head out after lunch to visit the farm clients, but first there is a donkey to attend to. Donkeys come in different sizes; this one, a “standard,” is nearly as tall as a horse. A man in town borrowed his friend’s horse trailer to transport the patient to the clinic, where it is standing outside the big door to the back room. For the moment, that is as far as the donkey will go.

The man, who says he bought the animal for his girlfriend and has kept it in his back yard as a pet, needs to move it somewhere for the winter. The problem is that none of the farms where it might board will take an intact male donkey, or jack. As Vosburg points out, such a donkey “will try to mate with everything” and can be very disruptive. So the animal is here to lose its massive testicles, but only if we can get it inside.

Vosburg grabs a stout rope and hands me one end. We loop it behind the donkey’s butt and, standing on either side of the beast, we pull. The donkey edges forward. Its owner pitches in, leaning hard against the butt; another inch. It takes us about fifteen minutes to get the animal inside, after which we’re all breathing heavily. Later, Vosburg will speak of the animal’s famously “resistant nature,” and his father, Don, an amiable and iconoclastic farrier — that is, an expert on horse hooves and shoeing — will observe that nowadays few donkeys are anything more than “field ornaments.”

Vosburg had already moved a giant gym mat to the center of the floor. The donkey is tied up nearby and anesthetized with an injection; slowly it collapses onto its side. The deed is done, and the next job is helping the donkey to wake up. It wants to stand before it’s quite able, and Vosburg doesn’t want it to fall and hit its head. We position ourselves once more on either side of the big jack as it steadies itself in what Vosburg calls a five-point stance — four legs and a nose resting on the floor. Then we stay at the ready as the donkey finally staggers to its feet, swaying from side to side. It leaves the clinic readily enough. Outside, though, it prefers not to enter the trailer. Here we go again.

I didn’t really understand what I was looking at around Hampton until my third trip: I couldn’t grasp how it was changing. From the road you see fields, farmhouses, barns, sheds, and the occasional grain silo. You don’t understand, unless you’re from the area, that this farmland, with its epically rich soil, some of the most productive on earth, sells for up to $10,500 an acre, and that a person who owns some of that land is possibly quite wealthy. I had driven back and forth a dozen times past a large poultry shed set a couple hundred yards off the road before I understood that this was the face of industrial agriculture: not something with belching smokestacks, just a bland metal building with a lot of square footage and thousands of chickens inside.

Similarly, I missed the hog barns — or CAFOs, concentrated animal-feeding operations — until Vosburg noted that they were right in front of me, about every three miles. These were long, low sheds of recent vintage, unexceptional to look at but fairly momentous to ponder once you realized that each was packed with a thousand or more hogs that could weigh up to 300 pounds apiece. I’d expected corporate signage and vast parking lots, but Vosburg straightened me out. Rather than occupying separate industrial parks, he said, the facilities (he avoids the word “CAFO”) were more like add-ons to existing farms.

Until the 1970s and 1980s, hog barns were modest structures of brick or tile block, containing between fifty and a hundred inhabitants. A few of these, now repurposed or abandoned, can still be seen in the area. But in recent decades, the CAFO has transformed agriculture. A row-crop farmer wanting to maximize the value of his property will often enter into an arrangement with a big food company. Sometimes the company helps the farmer secure a loan to build sizable sheds by promising to buy his hogs for the next ten years. It is the farmer’s job to manage the CAFO — but the corporation spells out the terms of its operation, which tends to be highly automated, requiring few employees. The corporation also supplies the animals, feed, water additives, and veterinary care.

The waste materials from CAFOs are a growing problem in Iowa. Liquid manure collects under the sheds in massive lagoons (pigs poop directly into them) and can leak into the soil and groundwater, and pollute the air. Once treated, the slurry can be used by the farmer to spray over his fields as fertilizer. Dead hogs, too, are sometimes ground up and spread on the fields, a practice I discovered when I asked Vosburg and his father about the large birds of prey circling overhead.

“Those are bald eagles. They didn’t used to fly all the way over here,” Don said. He explained that the birds are more commonly seen along the Mississippi River, one hundred miles from Hampton — but when the weather gets cold, they start showing up. “We’ve turned them from fish eaters into carrion eaters,” he said. “In wintertime, they’re out there feasting.”

This style of agriculture has been hugely productive and hugely profitable — and it is hugely vulnerable. A virus known as porcine epidemic diarrhea swept through Iowa in May 2013 and went on to kill more than 10 percent of the nation’s pigs within a year: as many as 7 million animals. Farmers also worry about swine respiratory disease and are embracing elaborate biosecurity measures to keep it out of hog barns. A visitor to these facilities essentially needs to scrub in and out like a surgeon — one local worker described changing and showering seven times a day as he went from building to building. When I asked to peek into a CAFO one day after we finished a chute job, Vosburg told me it would be impossible: the farmer was too scared of infection.

Years ago, Dr. Flick (as everybody called Flickinger) made a big part of his income tending to hogs. That’s all changed. These days, despite living in the nation’s number-one pork-producing state, Vosburg earns very little money on pigs. The corporations that control the CAFOs supply their own veterinarians, who are specialists. Vosburg has heard that the best-paid veterinarian in Iowa is such a person. Bertram and Ranes, who both grew up in the area, know others from Iowa State who took that route; they dress for the office instead of the barn, and “bring their laptops home at night,” as Bertram put it. It’s more money. But it’s a different life.

For the most part, Vosburg’s clinic exists on the edge of this corporate economy. The food animals he tends to are mainly cattle. Apart from veal calves, cattle usually grow up outdoors. Typically, in the Midwest, they are adjunct sources of income on mom-and-pop farms that raise corn or soybeans. A farmer might have from forty to 120 head of cattle, and use his or her own grain and alfalfa to feed the animals.

Lately, beef prices have been high. When your herd of a hundred cattle is worth as much as $200,000, you will gladly pay a veterinarian to keep them healthy, and that’s been a boon to Vosburg. “We’re doing business like we’ve never done before,” he told me. “But to a certain extent, all it does is make up for times when things weren’t so good. We’re riding the wave up, and at some point that wave’s going to break and we’re going to crash.”

Vosburg is round and short but not fat. He looks like a muscular hobbit with glasses, and he knows it; just like a hobbit, he jokes, he enjoys a second breakfast. He likes to laugh. He does not have an ironic sense of humor, and a riddle he told in the staff room went like this: How do you catch a unique rabbit? You neak up on it!

A country vet needs a good truck, and Vosburg’s is a newish, black Ford F-150 Lariat pickup with an extended cab and a big pile of boots, clothes, and magazines in the back seat. Permanently installed in the bed is a large white chest: his traveling medicine cabinet. It has a built-in heater so that medicines won’t freeze in the winter. Vosburg spends a lot of time in the truck, puts many miles on it, and he tells me that road accidents are almost inevitable. Dr. Flick, he says, saved the tailgates of all the pickup trucks he rolled and wrecked over the years: “I think there were five or six.” (So far Vosburg has rolled and wrecked a truck only once, when a deer jumped onto the road in front of him.)

He is chatty, an unusual trait in country veterinarians. At a farm we visit one September morning, whose owners are known as Big Vic and Little Vic, Vosburg keeps up a constant stream of repartee as he vaccinates the Angus cattle and affixes tags to their ears. Big Vic’s wife, Julianne, stands by with a clipboard, and eventually she quips: “The only time Zach don’t talk is when he has a tag in his mouth.” In this respect he is the polar opposite of Dr. Flick, she says. “The guy before would say maybe ten words in an entire morning.”

Little Vic has an active breeding program, choosing promising calves to keep intact as bulls. The rest of the males, however, he wants castrated. Farmers over the years have seen the benefits of this practice for herd management: intact bulls are aggressive and can injure other cows. Castration is accomplished with a tool that places a rubber band around the top of the scrotum. Once the first of Little Vic’s bulls is restrained in the headgate, a neighbor holds its tail up, which keeps it from kicking with its rear legs, and Vosburg reaches in, grasps the scrotum, and ratchets on the rubber band. This stops the flow of blood; in a few weeks, the gonads will simply fall off.

The job goes smoothly. Everything was prepared before we arrived, the cattle rounded up and ready to be herded into the chute. Big Vic and Little Vic work well together, funneling animals into the chute while leaving the operation of the headgate to Vosburg — a good idea, since he does it day in and day out. The atmosphere is cheerful. Arriving back at the clinic that afternoon, spattered with mud, Vosburg happily asks the staff if they like his hair with “manure-colored highlights.”

A visit to another farm, in November, presents a different picture. It’s a frigid day, for starters, just above zero. Nobody is waiting for us outside, but Vosburg knows where to go: he climbs down from the truck, opens a gate, and parks inside a pasture near the chute. It’s clear that the setup hasn’t been used for months. (“Probably a year,” says Vosburg.) The chute itself is overgrown with dead weeds, some as tall as we are. I set to work clearing it out while Vosburg lowers his tailgate and begins setting out the tools and medicines he’ll need, starting with the jug of Ivomec — an antiparasitic medication that gets poured along the animal’s back — and the vaccination guns. He has brought a Styrofoam cooler filled with warm water; after placing it on the open tailgate, he drops the vac guns into the liquid, needles first, to keep them from freezing. (Some of the needles will freeze anyway.) The bottles of vaccine he keeps in a plastic lunch container, in the back seat of the truck.

After fifteen or twenty minutes, the farmer appears with a neighbor, and they finally begin herding the cattle toward the chute. I’m not sure whether the animals are more ornery or the cattlemen less talented, but it’s a slow process with many setbacks. Several cows are determined to keep their distance, despite concerted hooting and arm waving. At one point, the farmer and his neighbor pick up a section of metal fence in order to block off the escape routes for these intransigents. One cow, however, chooses to crash directly into it, throwing the neighbor flat on his back. He is slow to pick himself up, thinks he might have broken a rib. Vosburg, meanwhile, decides to get started with the animals that have already been caught.

The headgate is rusty but functional, and progress is made. The preg checking is hard on Vosburg, because he has to take off his coat and expose his bare arm in the bitter cold. Inside the cow, of course, it’s warm — but he’s usually not in there for long. He asks me to pour fresh Lubiseptic onto his latex glove now and then, but expresses little gratitude: “There’s nothing I hate quite so much as cold lube on my arm on a cold day.” Presently his glove gets a tear; we can tell from the green layer of manure inside. He does a couple more preg checks and then rinses and retires to the truck cab to warm up while the farmer gathers the bulls to be castrated.

This time Vosburg uses a Henderson castrating tool (essentially a clamp attached to an electric drill) for what he refers to as “open castration.” It’s faster and cheaper than the other technique, in part because it doesn’t require a tetanus shot, as banding does. The process begins when he reaches down, cuts opens the scrotum with a knife, and pulls out the testicles. Then he takes the Henderson tool, clamps the cords that join the testicles to the body, and spins them around until the twisting snaps the cords and the testicles fly off. They drop onto the frozen ground alongside the chute, where two farm dogs greedily grab them and run off. Over the next hour or so they devour, I think, sixteen testicles.

It’s difficult to tell how much this hurts the bull. Most cattle locked in the headgate will moo; some of the animals getting preg checked or castrated seem to moo a little louder. They swish their heads and stamp their feet. As one poor steer-to-be brayed in the gate, a big cow we’d already vaccinated (Vosburg guessed it was his mother) came back over from the field and studied the animal from up close. To me, that looked a lot like a social response to pain.

Many veterinarians, including Vosburg, say that castration is important for reducing aggression and violence among cattle. It also improves the flavor of the meat. Turning bulls into steers, Vosburg likes to say, “makes it a better world.”

Renee Bertram listens to the breathing of a dog that is receiving anesthesia before surgery at Hampton Veterinary Center in Hampton, Iowa

But he acknowledges that procedures like castration and horn removal probably cause pain. The workarounds, he says, take time and therefore cost money. In other words, anesthesia could be administered before such procedures, by running each animal through the chute twice — but farmers don’t want to pay the additional costs. Nor do consumers, says Vosburg, floating the prospect of “twenty-five dollars a pound for ground round.” He’s not against such measures, should the law eventually change. He believes that such a change might be in the offing, since more and more municipalities are regulating practices such as feline claw removal or the tail docking of dairy cows. He also concedes that there might be compelling medical reasons to help the animals cope with pain. The instructors at a recent continuing-education course, he recalls, “proved that recovery will be faster and smoother with pain control. It’s not necessarily that hard to do.”

But getting too far ahead of the professional consensus on matters like pain control may have its costs. Jim Reynolds, a veterinarian focusing on bovine medicine, has chaired the animal-welfare committees of both the American Veterinary Medical Association and the American Association of Bovine Practitioners. In 2009, he testified before the California State Senate in favor of restrictions on tail docking. According to Reynolds, this testimony contributed to the loss of his job as a clinician at the University of California, Davis. “The dairy industry is a major funder of research at land-grant colleges in California,” he told me. (The university insists that Reynolds “received strong support and encouragement” throughout his career at Davis. He now teaches at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California, where, he said, “I am allowed to express my views.”) He sees tradition as the biggest culprit in the toleration of animal pain. “Vets working with livestock tend to do what they saw done a long time ago. They get trained by older veterinarians, and for some reason they tend to rationalize the procedures.”

There is no question that pain occurs, he says, but vets have learned to ignore it. “It’s bad medicine,” Reynolds insists. “I completely believe that the veterinarian wants to do the right thing. I’m certain that same veterinarian would not perform a procedure on a horse or a dog or a cat without pain medication. As a profession, we have to get past saying that it doesn’t really hurt the animals — because it does hurt them. They have the same neurotransmitters, the same response, the same pain that we do.”

Hans Coetzee, a specialist in bovine pain management at Iowa State, has spent years conducting studies that measure the level of pain in cattle, partly in order to provide the FDA with the evidence it needs to approve a veterinary drug that can alleviate it. “I was absolutely amazed there are no drugs that are labeled for analgesia by the FDA,” says Coetzee, a native of South Africa who also worked in the United Kingdom for six years. He was reluctant to speculate about why his fellow vets were not more committed to such measures, but did report the kind of rationales he had heard from farmers: “Pain relief doesn’t make me money, it takes time to do, it’s expensive.”

A key factor in the status quo, Coetzee told me, is that “the majority of consumers are blissfully unaware that we don’t provide pain relief when we do these procedures.” If consumers knew what the animals went through, he suggested, things might change. Farmers, he feels, “need to see that there’s an upside to them for doing this.” Which is to say that sooner or later, consumers in search of ethically raised food may wish to avoid not only hormones and antibiotics but also needlessly inflicted pain.

Not all the pain belongs to the animals. Soon after my November visit, Don Vosburg wrote to tell me that a cow in a chute had swung its head suddenly, smashing his son’s hand against a bar. Zach’s hand swelled to the size of a melon for a week, making it impossible to do preg checking and other work.

The hand is back to normal in March, when I return to Hampton. It’s a regular Monday at the clinic, with Bertram and Ranes looking at pets in the examination rooms and Vosburg, in the back, vaccinating and rubber-band-castrating calves. Usually the clinic’s chute is an ideal place for him to do this: he is indoors, has all his tools at hand, and can otherwise control the environment. But not, as it turns out, today.

He has stepped into the chute behind a bull in the headgate when Karen Symens, his receptionist, walks into the room to ask him a question about scheduling. It is, he will decide in retrospect, neither a good time for her to ask a question, nor for him to answer; he has just squeezed the bull’s scrotum. Perhaps the farmer in attendance, holding up the tail, has also been distracted, and let it down a notch. In any event, the bull kicks, and its hoof catches Vosburg on the left cheek, not far from his eye. Symens looks on, aghast.

“What can I do?” she asks.

“See if you can find my glasses,” he says. She finds them on the floor of the chute and gives them back to Vosburg, who finishes the job, then goes to the clinic’s freezer for an ice pack. Easier to use, he decides, will be a liquid pack of mixer for a Bahama Mama cocktail. He had bought it to celebrate the completion of a particularly difficult job, involving the vaccination and preparation of horses for export to a resort in the Bahamas. The assignment had become a bureaucratic nightmare, and now the celebration would have to wait until his head felt better.

At lunch, chewing his sandwich is painful. He asks Symens to reschedule all his afternoon appointments except one, which he knows to be truly urgent, and delegates me to drive his truck so that he can hold the ice pack to his head.

Even then, he keeps chatting. Vosburg tells me it is the second time he has been kicked. The first time, he was working for Dr. Flick — in fact, it was one of his first days on the job, and a disaster all around. He had failed to properly attach the trailer hitch on the mobile headgate that he was towing behind his pickup truck, and en route to the farm the trailer disconnected and rolled twice, end over end, a total loss. Getting kicked in the head a couple of hours later added insult to injury — or perhaps the other way around. When the job was over, he drove himself to the ER, where they told him he had suffered a mild concussion.

Vosburg, though young, already has other wounds. His exit from his mother’s womb resulted in nerve damage and Erb’s palsy, which left his right arm angled slightly away from his torso. “It basically has forced me to be ambidextrous, because I can’t turn my right hand over. If you look at my left forearm, it’s almost double the size of my right.” More interesting to look at, actually, are his hands, which are covered with scars from hooves, fences, claws, teeth, and even a scalpel that he dropped during surgery. (Bertram sewed up that cut for him.)

“Hey, don’t cry for me,” he says as we discuss his situation. “I’ve got two arms that work.”

As for getting kicked in the face, it was fairly common. Moving the ice pack up to his eye, which has nearly swollen shut, he asks if I remember the veterinarian we met in September at an equestrian event in Mason City. The man had a big scab on his upper lip and a red gash on the bridge of his nose, near where his glasses rested. “Kicked in the face?” I ask. Vosburg nods.

But none of that was as bad, he says, as a YouTube video his vet-school classmates at Iowa State had passed around. It shows a man being kicked in the chest by a horse he’s branding. The blow lands with such force that the man’s body flies out of the camera frame. “We’re told he died,” Vosburg said.

Despite its sizable staff, Vosburg’s clinic is very much a family business. Don Vosburg plays a vital if somewhat hard to define role. He takes care of the family’s horses (he and Zach have a herd of about twenty-five) and mules (he has several). A former agriculture journalist, he likes to photocopy pertinent articles and distribute them to the staff — the last one was about pit bulls, from Esquire. He listens to NPR. He’ll use the term “CAFO,” which others shy away from, he’ll tell you that Iowa’s strict ag-gag laws are harebrained, and he’ll complain about crop dusting, which sends pesticides drifting into the houses of his children and grandchildren.

Father and son are exceptionally close. Don was the best man at Zach’s wedding, and they eat breakfast together every Saturday at the 7 Stars Family Restaurant. More frequently, Don can be found sitting at Zach’s desk, using the fast Internet connection to check out advertisements for horses and making himself available for equine house calls. In those cases, he accompanies Zach, and the client gets the benefit of his expertise for free.

Don had once thought of becoming a veterinarian himself. Back in the 1970s, he says, when he first considered applying, schools of veterinary medicine were extremely selective, taking about one in ten applicants. By the time Zach entered Iowa State, admissions standards had relaxed somewhat, and Don’s dream reawakened. He took some required courses, applied again, and, to his amazement (and that of Zach, who was entering his third year), he was admitted to Iowa State.

The school was intrigued by the father-and-son act. Don showed me a souvenir of those days: a copy of the university’s alumni magazine with a full-page photo of the two, wearing white lab coats and stethoscopes and kneeling next to a big mutt. calling dr. vosburg, dr. vosburg, read the headline. The story was almost too good to be true — and, indeed, it didn’t last. Don pointed out a vein visible on his forehead in the photo. “That’s from the high blood pressure I had,” he said. During the spring semester, his mother died, his coursework piled up, and the stress of finals overwhelmed him. Beset with hypertension, Bell’s palsy, and plummeting grades, he was forced to withdraw.

Zach says that being enrolled at the same school as his father was “the coolest thing we’ve ever done. We used to cook together, study together. We’d come home once a week to feed the horses.” He also allows that it was “probably my biggest heartbreak — an absolutely beautiful nightmare.”

Both Vosburgs now teach classes at a nearby community college, Don on farrier science and Zach on basic veterinary medicine. Don is a fixture at the clinic and around Hampton. He owns several old Buicks, borrowing from one to fix another; sometimes you’ll see one of his fleet parked in town, a bale of hay tied atop the trunk. He’s bald and bearded and big and Zach reports that his father, who can toss a bale with a single hand, wants his epitaph to read exceptional upper-body strength.

In his books about working as a veterinarian in rural Yorkshire, James Herriot wrote less about animals, more about people. There was the wealthy woman with the coddled lapdog, the farmer’s uncle dispensing advice while the vet struggled with a colicky horse, the invitation to supper in a warm kitchen after hours in a freezing paddock.

Some of the time, daily life at the Hampton Veterinary Center seems worlds away from what Herriot described. When Bertram finally gets a call to work with hogs, it’s just to certify the cause of death for insurance purposes: around seventy-five animals died in a CAFO when poisonous gas leaked up from the sewage lagoon underneath. Their corpses were a dark-purplish color, and Bertram doesn’t really want to talk about the nightmarish scene.

Seventy-five is a tiny number, of course, compared with the millions of hogs that have died from porcine epidemic diarrhea, or the 30 million poultry euthanized over the past year in Iowa as a result of the avian-flu scare. The latter disease is almost unbelievably contagious, Vosburg tells me one morning at the clinic: if just a single chicken in a big operation is found to be infected, “they eradicate every living bird on that farm.” He gestures at the two dozen eggs that Big Vic and Little Vic had dropped off as a gift earlier that day. “We may be relying on backyard flocks for a while,” he says.

When I comment on how frequently these epidemics seem to be hitting Iowa, Vosburg suggests taking a longer view. Such events are not unique to the Midwest or even to the United States, he notes. In 2001, during an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease, every veterinarian in the United Kingdom was working all day, every day, to euthanize cattle. An earlier outbreak of the same disease, in 1967 and 1968, led to the slaughter of nearly half a million cows and sheep, many with pistols.

Still, despite the great livestock epidemics swirling outside, life inside the Hampton Veterinary Center more often resembles a prelapsarian scene from the 1940s — something that Herriot would have recognized in an instant. One day a farmer brings in an aging black dog, and I join Bertram as she lifts the old boy onto the examination table. The dog mainly lives in a doghouse, says the owner, who does electrical work to make ends meet, often not arriving home to feed the animals until after dark. That’s why he hadn’t noticed the sores spreading over the animal’s body, hadn’t looked closely until the dog stopped eating.

Bertram looks closely now. She sees sores on the dog’s lips and gums, more on its toe pads, others peeking through its fur. The room smells bad, and Vosburg comes in to look. “May be pemphigus,” he says, and Bertram nods. They discuss how to treat the dog: if you give it steroids and the infections are fungal, that can make them worse. Bertram takes a urine sample, and the dog is moved to a stall in back so that the exam room can be mopped and wiped down with Clorox.

The dog’s condition and prospects remind Vosburg of a black Lab he’d had to put down recently, and the anguished response of the owner. “You know, the guy we worked with,” he reminds me, mentioning a farmer we had visited for a chute job. It’s hard for me to picture this particular man getting emotional, but Vosburg recalls that the whole family came to the clinic to say goodbye. They gathered around the dog on the carpeted floor of the main office and recounted episodes from his life: for example, how he had learned to swim across a creek with one end of a rope in his mouth to deliver it to the farmer’s son on the other side. It was very tearful. Then the family left and Vosburg euthanized the animal. It was horrible, he says. “Academically, you know it’s right. But here,” he says, touching his heart, “it’s all torn up. I feel someday I’m going to have to answer for all the animals I put down.”

As for the black dog with the sores, it was suffering from blastomycosis, a systemic fungal infection. Bertram sent it home with medication, but the animal ended up dying.

Death is hard on the veterinarians, and fatigue is hard. To relax at the end of the day, Zach feeds his own animals. In March, I followed him as he made the rounds in the barns behind his house. He fed three cats and a rescue bunny, two elderly horses (one named Jimmy, toothless, that he’s owned since high school), five goats named after characters in The Lord of the Rings, a new bucket calf named Pikachu (fed with a bottle), and last year’s bucket calf, Buddy. (“Pretty soon we’ll eat it.”)

Then it was on to a dozen or so big horses kept outside, whose hay Vosburg carried from the barn. “It’s my mental health,” he said as they milled around him. It was a relief to do work that was not at the behest of a paying client — and horses simply made him happy. One of the best smells, he told me, was that of a hot horse that had just been ridden, and he liked to quote the proverbial line, “There’s something about the outside of a horse that’s good for the inside of a man.”

During the shorter days of winter, it would be dark out by the time Vosburg finished these chores. He’d have supper with Alexis and the boys, help put them to bed, then stay up for a while, typically in a big recliner in front of the TV, watching and dozing until eleven o’clock, when he would call it a night. “That’s about when the last farmers check their stock,” he said. If they hadn’t found a problem by then, it would wait until morning.

In birthing season, however, all bets were off. A lot was at stake financially for farmers between February and April, and Vosburg wanted them to know that the clinic was there for them. He rotated on-call duty with Ranes and Bertram, but sometimes he was summoned even when it wasn’t his turn: two emergencies might arise at once, or one of the vets would call with a “situation” — he had told them not to hesitate in such cases.

On my first night back in town in March, I join a family dinner on a Sunday night at Hampton’s Chinese restaurant. Vosburg arrives late and can barely keep his eyes open: the weekend had been one “cow OB” call after another. They did not all have happy endings. He had attended to one prize cow whose calf was stillborn; the farmer had been very upset, though not at him. Immediately after, Ranes had called from the site of another labor: she had reached into the cow’s womb and felt the calf, she reported, but her hand had passed between two ribs. “It’s dead,” Vosburg confirmed. “Pull it out anyway.” While Ranes was doing that, she got another call: a breech birth. Rotating a backward calf in the womb takes muscle, so she called Vosburg again. He was in the southeastern part of the clinic’s service area and the cow was in the northeastern, but he took the call.

I am keen to see a cow OB myself, but of course Vosburg can’t control their timing. The closest we have come so far is a prolapsed uterus. A cow that had given birth successfully just kept pushing, until her uterus hung down from under her tail. “Picture the biggest garbage bag you ever saw,” Vosburg had told me by way of preparation. After nearly an hour of wrestling with the organ, he succeeded in stuffing it back inside.

At the end of that week in March, though, we are called out to a farm where a cow named Buttercup is having a difficult labor.

“Really?” I say. “They really named it Buttercup?”

“I know,” Vosburg responds. “Most places, it’s 15-01-A or Red 45. But this place, it’s Buttercup.”

The scene at the farm is vintage Norman Rockwell. The farmer, his kids, and his grandkids are all resting on or looking through a wooden fence at Buttercup, whose new calf is about five minutes old. Buttercup licks her, and she tries to stand. The sun is just setting; it lights the inside of the shed with a golden glow as the calf staggers to her feet, umbilical cord dangling between her legs.

“Guess we can’t show you one after all,” Vosburg says, as we head back to the truck. I tell him that I’m the opposite of disappointed.

Still, when my phone wakes me up a little before midnight, I am excited. “Cow OB at the clinic,” says Ranes. “Pick you up in five minutes?”

I go down to the lobby of the motel — which, incidentally, has a canoe that Vosburg built hanging on the wall. (He’s not thrilled by this homage, because the owner of the motel seems to have drilled holes through the bottom of the canoe in order to mount it.)

At the clinic, the farmer and his daughter help run the cow through the chute, and Ranes closes the headgate. She scrubs up, puts a latex glove on her arm, and reaches into the uterus. “Good position,” she announces to the farmer. Then she looks at me. “Want to see?” By which she means feel — and I do. My own gloved hand soon encounters the front hooves, just a few inches inside the womb, and beyond that, the calf’s head. Touching the head — the face — is an unexpectedly powerful sensation. The previous fall, after a morning of preg testing, Vosburg told me that he never tired of feeling a calf’s head and “holding God’s creation in the palm of my hand.” It struck me as sort of corny at the time, but now I understand. This fetus is minutes away from becoming a calf.

Ranes gets the calf jack and attaches it to the wall of the chute behind the cow. She loops two little chains around the hooves, which are still inside the womb. Then she begins to tug gently on the jack handle. With every motion, the calf advances half an inch or so into the world. Click-click, click-click is the sound of an assisted cattle birth. First the tips of the hooves appear. Then some leg, more quickly. Things slow down as the head squeezes through, but then speed up again, and Ranes catches the emergent calf at the last second, slips off the chains, and carries it around to the floor in front of the headgate. The mother immediately begins to lick the pale wet baby, and the pale wet baby comes to life. The floor is concrete and the light fluorescent, but the result is the same as I’d seen earlier that day, at dusk: a new calf.

The farmer and his daughter stand back, letting Ranes and the cow tend to the newborn. I finally notice them, and remember that they have a stake in the proceedings.

“So, what do you think?” I say, by way of making conversation.

The farmer treats it like the silly question it is. “What do I think? Hey, I’ve got a living calf. What could be better?”