Discussed in this essay:

Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power, by Steve Fraser. Little, Brown and Company. 472 pages. $28.

Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence, by Bryan Burrough. Penguin Press. 608 pages. $29.95.

The Edge Becomes the Center: An Oral History of Gentrification in the Twenty-First Century, by D. W. Gibson. The Overlook Press. 320 pages. $27.95.

For years I lived in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, which was shared by the students and faculty of Columbia University and impoverished Hispanic and black people. When winter turned to spring and the days grew less cold, the sad, timeless division between the poor and the materially well-off made itself apparent in a particularly vivid way. As temperatures climbed into the fifties, you could tell the Columbia people from everyone else by a simple method. The students and professors wore shorts and sometimes flip-flops, while their neighbors kept winter coats and parkas on well into April. They were poor. Their feeling of vulnerability was not diminished by a warm day in spring.

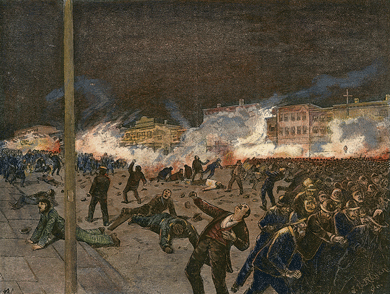

Engraving of a mass meeting in Tompkins Square, in New York City, in support of the Great Uprising of 1877 © The Granger Collection, New York City

One of the peculiar things about economic inequality is that the people who are most articulate about it are not poor, while the poor themselves have said little, at least in print, about their situation. There are exceptions, like Cadillac Man, who wrote essays about his many years of homelessness and then published a book in 2009, but these days most writing on poverty is left to privileged opinion writers and reporters. Of course, you don’t need to have experienced poverty to write about it. What you need is to be injured, angered, or embittered in some fundamental way, to have experienced pain and humiliation. No class is immune to that. From Karl Marx to Dorothy Day, the revolutionary or reformist spirit has often been embodied by materially comfortable people who, by some serendipity of character or circumstance, are preternaturally sensitive to material suffering.

Who writes the accounts of poverty in our time? Who reads them? We are surrounded by fine, noble, sometimes furious discontent. Reports and commentary about poverty proliferate. The quality of investigation and analysis is often superb. Yet it all seems to take place in a vacuum. Last year, Ta-Nehisi Coates published a long essay arguing that America should pay reparations to its black citizens, especially those most impoverished, for the atrocities of slavery and the effects it has wreaked on black life through the generations. Liberals roared their approval, praised Coates for his courage, and then the news cycle turned up something else for them to talk about. It was clear that such people had little or no stake in any of the issues he was addressing. The ones who did were too busy drowning in their circumstances to be aware of it.

Steve Fraser’s Age of Acquiescence is a long but briskly told history of how concentrated wealth gradually made money king, turning owners — of land, houses, and labor — into renters and mortgage holders subject to the fluctuating economic needs of larger entities. It is an old story, going back to Marx’s Capital, but the deep roots are precisely Fraser’s point. The problem, he argues, is that whereas great disparities in wealth and power once gave rise to social dissent and political upheaval, the mass movements of social reform that occur now, such as Occupy Wall Street, are rarely more than fleeting provocations.

Fraser offers a number of persuasive, if unoriginal, reasons for this change, and they are all the more frustrating for being rooted in seemingly immutable historical forces. The most obvious reason is that the momentous upheavals of the past, such as the Great Uprising of 1877 — America’s first nationwide workers’ revolt, and Fraser’s representative instance of organized dissent — occurred at times when older social forms were clearly visible even as they were being swept away by change. During the Gilded Age, the farmers of the late nineteenth century remembered how it had been before the banks appropriated their land and rented it back to them; small tradesmen recalled the modest shops they’d had before they were bought out and turned into workers for hire. Newly emancipated black slaves had gone from bondage in the South to another sort of slave labor in the North, where they were forced to buy food from and pay rent to their employers, who possessed the legal right to jail them if they tried to quit without first paying off their exorbitant debts. White farmers and tradespeople became nostalgic for a time when their material welfare was unmediated by so many third parties — the banks, the company bosses, the lawyers, the agents of one financial service or another — while the recent black migrants to the North remembered when they’d been promised that they could be free.

Occupy Wall Street protesters in front of the New York Stock Exchange, September 28, 2011 © Reuters/Brendan McDermid

Fraser’s other reasons for the lack of social upheaval today are more abstract. One is the prevalence of language and techniques that Herbert Marcuse once referred to as “repressive tolerance,” which exploit personal freedom to keep people in line. In other words, you can now fuck whomever you want however you want; just don’t think you’re going to be able to afford a decent health-care plan or a house anywhere you’d like to live. Fraser refers to the contemporary myth of the financier as rebel, and to the fairy tale of a buoyant stock market that lifts all boats. He speaks of the “ubiquity of market thinking,” the way in which commercial values have colored the emotional and psychological aspects of our lives. In his view, radical causes are inevitably converted into paths toward personal fulfillment or compromises with the status quo.

This is all familiar enough. Fraser complains that “environmental despoiling arouses righteous eating; cultural decay inspires charter schools . . . the break with convention ends up as the politics of style.” Well, so what? We would be lucky if eating healthy food, building charter schools in poor neighborhoods, and making personal statements through clothes and gadgets were the worst problems society had to endure. Would Fraser rather see the poor deprived of material consolations or empowerments that allow them to persevere, in hopes that their desperation would lead them to rebellion? The obstacles to mass economic protest are not the daily ameliorations that enable the poor to feel good about themselves, however tenuous that feeling may be. The obstacle to mass economic protest is the lack of particular faces, names, or circumstances that people can organize their protests against.

In today’s America there is no legalized child labor, no military draft, no explicit segregation. For all of Occupy’s admirable rage against the banks, there is no single egregious economic issue to rally against. Instead, there are about a million subtle degradations in the quality of many people’s lives. Material suffering has become customized. People are up against a dizzying variety of problems. This person struggles under credit-card debt incurred from medical expenses, that person is sinking under student loans. This one’s job has been outsourced, that one has been laid off because of her age. The endless list of economic burdens and barriers makes organizing a mass movement against rising inequality a daunting task. Perhaps the most painful social paradox of our time is that we are able to see through the lies and machinations of power as never before, yet the more we know about this increasingly sophisticated mendacity, the more abstract and diffuse it appears, and the less we seem able to act on what we know.

Causes benefit from centralization as much as reformist governments do. Mass protest movements, even revolutions, usually start with a small, unifying outrage: cruel tax policies in eighteenth-century France, arrogant tax policies in Colonial New England, draconian pay cuts to workers on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in 1877, the murder of three young Freedom Riders in Mississippi in 1964, police suppression of the Free Speech movement in Berkeley, police harassment of customers at a small gay bar in Greenwich Village. You might say that mass protest proceeds inductively from specific events that are clear and concrete in their injustice. Occupy Wall Street certainly captured people’s imaginations, and, as Fraser points out, it may well have fostered the populist sentiment that led to the elections of Bill de Blasio as the mayor of New York and Elizabeth Warren as a Massachusetts senator. But for all its smart and honorable intentions, the movement proceeded deductively, from the premise that the entire capitalist system, whose home was Wall Street, was responsible for our ills — a bit like a biologist announcing that mortality is responsible for death. Occupy’s premise was general, abstract, and tautological. (The bonuses awarded to AIG executives in 2009 were the rotten fruit of the matter, not its root.) Even the name was hard to grasp. Why occupy a physical street when the injustice is hidden by and diffused through myriad legal and semilegal practices and conventions, in thousands of offices, with connections to every part of the country and the world?

Perhaps the most universal, and potentially galvanizing, economic outrage in our society is student-loan debt. A monthly nut of $500 or more is one of the greatest obstacles for young people seeking upward mobility. It binds their plight to that of the poor, whose monthly struggle to meet their financial obligations makes it impossible for them to consider even the most modest community college. Focus on the pain caused by overbearing student loans and the widespread disfunction of our economic system will be exposed: the sham of retail higher education in a supposed democracy; the untenable position of the middle class; the indissoluble bond between money and so-called merit; the tendency of modern American governments to turn to banks instead of taxes for cash. One person’s story would lead to other people’s stories: children burdened by unfair debt would lead to their parents who, for one reason or another, could not afford to pay for college, and on and on. The screws on the poor and the screws on the middle class would be revealed to be turned by the same implacable tools.

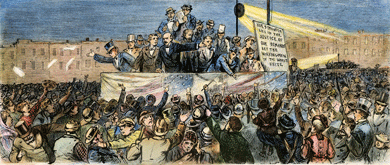

The consequential effect of these stories would depend on how quickly they were spread and listened to. You would think that might be the easiest thing in our digital world. But it’s more complicated than that. Throughout his book, Fraser describes a unified, purposeful stream of free expression that once made social-protest movements possible, though he never explores the nature of present-day public expression. In 1886, he tells us, protesters gathered in Chicago’s Haymarket Square to demonstrate against the police slaughter of six workers who had been on strike against the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. A bomb went off in the square and killed a policeman, after which the police fired on the crowd, killing a handful of protesters and injuring hundreds more. A trial followed that was widely perceived to be fixed; Chicago’s anarchists were blamed for the bomb, and widespread persecution of social radicals ensued.

In response to the violence against labor and its advocates, Fraser writes, a “culture of opposition” was formed. It encompassed “Knights [of Labor], Nationalist clubs, populism, antimonopoly organizations, local labor, and Greenback Labor parties.” The potent and beautiful thing about this culture was its way of “leaping across boundaries of skill, gender, nativity, ethnicity, and race, winning the support of many people whose immediate economic interests did not depend on the outcome.” Fraser is excellent on the decline of the labor movement and of unions, but he doesn’t explain why the culture of opposition appealed to people with no ties to or even sympathy for the labor movement.

Yet the appeal is significant. The culture expressed itself in a flood of essays, pamphlets, articles, and books like Progress and Poverty by Henry George and Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel Looking Backward. Calls for the government to issue paper currency that would amplify the money supply and allow farmers to retain their land, pleas for government-created jobs, demands for an eight-hour workday — these were, first of all, shared by people bound together by a single passion. But they also became a part of genteel literary culture. Educated, cultivated people found that they were being unfashionable if they didn’t familiarize themselves with the new, radical ideas about capital and labor, and if they didn’t profess solidarity, whether sincere or not, with the new values.

In our time, the Internet giveth the impetus for social change and taketh it away. Social media can make a cause go viral and send people pouring into the streets, as the Occupy movement demonstrated. A video filmed on a smartphone — Walter Scott shot in the back by a cop in South Carolina, Sandra Bland violently and wrongfully arrested in Texas — can fasten outrage to a particular injustice. But the relentlessness and instantaneity of the Internet also quickly turn shocking and infuriating incidents into old news — as the Occupy movement demonstrated.

In Days of Rage, his gripping story about America’s violent counterculture in the 1960s and ’70s, Bryan Burrough explains that, contrary to myth, Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers, the leaders of the Weathermen, the violent underground movement, did not “operate from grinding poverty or ghetto anonymity: For much of their time underground, Dohrn and Ayers lived in a cozy California beach bungalow, while the group’s East Coast leaders lived in a comfortable vacation rental in New York’s Catskill Mountains.” Dohrn grew up in an affluent suburb of Milwaukee; Ayers’s father served as the CEO of Commonwealth Edison in Illinois and had a college named after him. Mark Rudd, another member of the Weathermen, and Tom Hayden, who helped found Students for a Democratic Society, hailed from middle-class backgrounds. The same went for Abbie Hoffman, one of the founders of the Yippies, and for countless other members of both the violent and the nonviolent wings of the political counterculture.

Toward the end of his book, Burrough asks former Weatherman Cathy Wilkerson, who was raised in a wealthy Manhattan family, what she thought she and her fellow terrorists had accomplished. She replies that she believes the example of the “choice” they made “to step out of the encasing, protective cover of privilege” inspired others to “armed resistance.” Then she adds, almost mechanically, “Our strategic choices were corrupted by the inherited arrogance of privilege.”

Perhaps it was the arrogance of privilege that made these people turn to violence in the first place. Burrough doesn’t pause to consider the obvious fact that the violence of the Weathermen helped to consolidate the power of the political hard right. American countercultural terrorism also ensured that people were reluctant to organize mass protest movements for fear of being associated with groups like the Weathermen and the Symbionese Liberation Army. (Recall Patty Hearst in her beret, holding a machine gun as the S.L.A. “brainwashed” her into helping them rob the Hibernia Bank in San Francisco in 1974, an incident that set back radical politics, and robbing banks, thirty years.)

Still, Burrough’s book is a useful collection of vivid testimony. Wilkerson’s jarring and irrelevant reference to “armed resistance” notwithstanding, her remark about “stepping out” of her social givens has a deep resonance. What Wilkerson is really talking about is confidence, the faith in a positive future that is one of the blessings of wealth. Such confidence is precious, especially now, when people are beset by a confusing blur of economic hardships, from underwater mortgages to outsourced jobs to draconian punishments for relatively trivial infractions.

It requires a tremendous feat of intellectual violence to imagine yourself in a materially different place from where you were born or grew up. Consider the humbly born Carnegies, Rockefellers, and Fricks, those living examples of Balzac’s observation that behind every great fortune is a crime. Driving rivals into bankruptcy and setting off bombs in public places perhaps have their roots in the same ruthless disregard for other lives. For all their madness, America’s homegrown terrorists made an important addition to the stock of alternatives to American reality. The spectacle of violence, as futile and counterproductive as it was, inspired the idea that social arrangements were not immutable. If an individual could go from rags to riches by an act of brute will, a society might go from poverty to equality by an act of collective will.

We live in an age of atomized economic suffering. As Celia Weaver, a housing organizer in Brooklyn, tells D. W. Gibson in his fascinating oral history of gentrification in New York City, The Edge Becomes the Center, new people moving into poor neighborhoods “maybe don’t have that different of an income than the longtime residents, but the income potential is different. . . . There are race differences, there are age differences, there are social capital, if not actual capital differences.” Some of these gentrifiers are people with the finest motives, who are sensitive to the material ordeals of the people around them. All but those from the wealthiest backgrounds could experience a reversal of material fortune in an instant. The youngest of them, living in cramped apartments with usurious rents, most likely have student loans to repay. They are socially removed from the poor and elderly people they are unwittingly driving out. But they are not that far removed.

Gibson’s book, with its many examples of people fighting the pulverizing power of concentrated wealth, is a somewhat heartening retort to Fraser’s pessimism. Amid all this social instability, the most effective social advocates are often people with the material ballast to keep their balance. Lacking material obstacles, wealth is able to keep an unobstructed view of the future. Gibson writes about forty-year-old Matt Krivich, whose affluent parents divorced when he was young. Krivich spiraled into anger and drugs, ending up addicted to heroin and living on the streets. Now he is the head of the Bowery Mission, in Manhattan, which offers food and shelter to thousands of homeless people every year.

Protesters at a Days of Rage demonstration in Chicago, organized by the Weathermen to protest the Chicago Seven trial, October 11, 1969 © David Fenton/Getty Images

“Money has presented us with an abstract of everything,” Spinoza once wrote. In a sense, these books by Fraser, Gibson, and Burrough are histories of the struggle for what you might call class confidence in the face of abstraction. The villains in all three books — in Burrough’s book, anyway, they appear as the villains for the counterculture — are impersonal forces so elusive that it is difficult to react to them effectively. The violence of the 1960s and ’70s now seems like an attempt to confront the abstractions of money with concrete realities. As for today, society seems to have acquiesced to the domination of concentrated wealth because, to a great extent, we are so inured to change that the idea of radical social transformation seems redundant or impossible. Gibson sums up the resulting state of affairs nicely:

We have settled into the choice to let money frame our relationship to land. This abstract thing called money is, itself, in the process of abstracting land: a patch of earth where a building was constructed and used for work and shelter by one group of people has become an investment for another group of people in another neighborhood or state or country.

You could say the same thing about the impossibly abstract nature of packaging basic human needs like shelter into derivatives, a practice still robust and healthy as ever. In some ways, the gap between rich and poor is really the chasm between people who flourish amid abstraction and are immune to the harsh edges of reality, and people who are deprived of material wealth and depend on matter for assurance that they are safe. In other words, it is the difference between confidence and lack of confidence. It is the difference between wearing shorts in March and a heavy winter coat in April.