The Ohio River runs through C. E. Morgan’s second novel, THE SPORT OF KINGS (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27). It’s a “hungry current,” a “sucking current,” a “swamping weight” whose black surface moonlight cannot pierce. It cleaves the green, fertile karst of Kentucky and the choking industrial cities of the North, a time-made path, wending through time. To swim across it, a runaway slave named Scipio kicks a drowning stranger in her pregnant belly rather than be dragged to death fathoms below. A hundred and fifty years later, toward the end of the twentieth century, Scipio’s great-great-great-great-grandson Allmon Shaughnessy sits at the riverbank and peers over at “the staunch antebellum houses glowing in the coming evening.” Allmon’s preacher grandfather warns him against crossing over, but warnings are beckonings, and history swallows its tail. Fatherless, impoverished, hardened by a stint at the state penitentiary, and hungry as the current, Allmon takes a job as a groom on the old Forge plantation, unaware that he has returned to the very family Scipio fled. That name, Forge — oh! Too many meanings to spell them all out here. Suffice it to say that rich, racist Henry and his withdrawn daughter, Henrietta, are queer birds gone mad for horses. They’re inbreeding Secretariat’s kin in a quest for genetic purity and the Triple Crown, because while The Sport of Kings is prodigious, magisterial, erudite, and aureate, it is never, ever off message.

Equal parts earnest social novel and multigenerational American melodrama, the book opens in the 1950s with young Henry under the thumb of his tyrannical father, a gentleman corn farmer who ties the boy to the old slave whipping post when he’s bad. Henry’s mother is loving and weak, the first of three women in the book who are unable to protect their children from the abuses of the world. What follows is a more or less straight downward trajectory for everyone involved, but the prose unfurls in sonorous digressions, unusual breaks in perspective and shifts of voice, and evocations of places as diverse as the cellblock and the breeding shed. Morgan, who is from Kentucky, lushly describes its landscapes. “Is all this too purple, too florid?” she asks at the end of one throbbing sequence. “Is more too much — the world and the words?” It was, at times, for me.

The Sport of Kings traces today’s socioeconomic injustices to nineteenth-century crimes, and the book is itself a curious mélange of nineteenth-century literary legacies. Morgan foregrounds the mighty gears of her machinery, proudly drawing attention to the book as a Novel with a capital N; she has no compunction about killing off a woman in childbirth or conjuring up a deus ex machina. The plot ultimately buckles under the weight, like Henry’s prized filly — bighearted, fat-assed Hellsmouth, who fractures her leg in the Laurel Futurity Stakes. A moral tale becomes a sentimental one. Did Morgan have to gild Henry’s lily-white villainy by making her inbreeding zealot commit actual incest? She can’t stick the landing, either. What might have been a delirious and haunting Pyrrhic victory, a spectacular scorched-earth finish, is undone with a lame epilogue.

The novel form arcs toward death, measuring consequences in lifetimes and generations. Some novels emphasize chance, or imagine humans as captive to destiny; others attend to problems of consciousness or moments of choice. But all make claims about cause — why lives turn out the way they do. These enduring preoccupations are posed explicitly by Morgan’s characters: Who am I? How is my life bound up with other lives? Is it possible to change my course? To that last question, Morgan offers a resounding “no.” For while she shares George Eliot’s fervor for connecting every detail of the plot, she is as dedicated as Zola to the fatedness of inheritance and the determining power of temperament and environment; with few exceptions, her characters are less responsible agents than they are the embodied forces of history and genealogy.

What was it that other Southern writer said? Something about the past? In The Sport of Kings, the past isn’t dead or undead — it’s an epitaph for the living. Henry becomes his own personal nightmare: his father. Henrietta wretchedly concludes: “You could never escape the category of your birth.” Allmon wears his circumstances like chains, living out a script “written in black blood on white paper” until a magical jockey named Reuben Bedford Walker III, an “imp, raconteur, pissant, tricky truculent slick,” a black man who knows the “cant of the Kaintuckee,” admonishes him: “Learn your history! . . . Your only choice was no choice!”

The great nineteenth-century characters are strivers and parvenus who maneuver in a world where wealth and position are established by birth. Time, alas, marches on. We moderns have no need for Balzac. We have sociology — longitudinal studies, to be precise. Taken in toto, their findings indicate that moving up the economic ladder today is about as easy as Rastignac’s conquest of Paris.

Helen Pearson’s THE LIFE PROJECT: THE EXTRAORDINARY STORY OF 70,000 ORDINARY LIVES (Soft Skull, $17.95) is a spry, if breathless, report on the history of five key British studies, which tracked cohorts born in 1946, 1958, 1970, 1991, and 2000–2001. You can learn a lot by following individuals over time. It’s thanks to cohort studies that we know that smoking causes lung cancer, that education causes women to delay childbirth, and that what you consume while pregnant can affect the health of your grandchildren. Cohort studies helped shape the British welfare state, including the National Health Service and early-childhood-education programs. Over and over they have confirmed the correlation of health, education, and success to parental income and class. What politicians do with the data, however, is not always predictable: “Cohort work showed so convincingly that people with a university degree earn more over their lifetime,” Pearson writes, “that it helped to convince the government to introduce tuition fees for university in 1998.”

The values and methodology are different, but the cohort study resembles the novel in being at once grandly nation-building and stodgily quotidian. Both seek to pinpoint the causes, the decisive moments, and the choices that shape the lives of “ordinary” people. (Is it merely a coincidence that the British played a decisive role in the history of the novel and of the cohort study?) Yet unlike the Up documentaries, which check in with individual lives periodically in the manner of a high-school reunion, cohort studies are broad and statistical. Early sweeps focused on education and home life and asked participants to keep diaries; now they resemble genetic data mining and rely on placentas, baby teeth, and blood samples. In the 1990s, silly fights over the cause of chronic disease — was it behavior? or fetal programming? — were finally resolved when epidemiologists concluded that multiple factors influence a person’s health. They call it “the life course model.” They could have learned it in English class.

“Yes, my dears,” wrote Nadezhda Aleksandrovna Lokhvitskaya, otherwise known as Teffi, addressing her fellow White Russian exiles in 1919. “There’s not much you can do about it.” Whether they had fled because of what the Bolsheviks stood for or because of what the Bolsheviks did, the result was the same. “You’ll all die together. Some from eating, some from being eaten. But ‘impartial history’ will make no distinction. You will all be numbered together.” She likened her generation to the Gadarene herd that stampeded off the cliff in the New Testament — the swine possessed by devils, the sheep following the swine. “They’re running after a way of life that is itself on the run.”

“The Gadarene Swine” is a highlight of TOLSTOY, RASPUTIN, OTHERS, AND ME: The Best of teffi (NYRB Classics, $14.95), a collection of remembrances and stories. Teffi can be folksy and corny (to prove how punctual she is, she writes, “When I was invited to a ball, not only did I not arrive late — I was a whole week early”), as well as dark and penetrating. She is a humorist and an eviscerator who sketches the spirit of the age in neat anecdotes, such as one concerning a wealthy actress who asks for a receipt after donating to the proletarian cause — she wants something to show to any revolutionaries who come around to rob her. Teffi wrote poems, feuilletons, plays, and fiction, and was so popular that candies and perfumes were named for her. She was a favorite of both Tsar Nicholas II and Lenin, though her description of the latter in an essay on her stint with the newspaper New Life is less than admiring:

Lenin didn’t even seem to look on himself as a human being — he was merely a servant of a political idea. Possessed maniacs of this kind are truly terrifying.

But, as they say, history’s victors are never judged. Or, as somebody once said in response to these words, “They may not be judged, but they do often get strung up without a trial.”

Tolstoy has many charms, but it is decidedly F.T.C.O.: For Teffi Completists Only. For everyone else, the book to start with is MEMORIES: From moscow to the black sea (NYRB Classics, $16.95), her witty and mournful memoir of the journey into exile. She left Moscow in 1918, intending to give a few readings in Kiev; she would never return. Published in Paris in installments between 1928 and 1930, Memories tracks a confusion of railway cars, rented rooms, steamships, and desperate, frightened nights. It has the feeling of an album of snapshots, though it is, of course, painstakingly crafted. Click: a former baroness, “squatting down and examining the floorboards with distaste through a turquoise lorgnette,” listlessly mopping with “a scrap of wet lace.” Click: Teffi’s “squint-eyed” impresario Gooskin, “slowly circling around” a German soldier “like some bird of prey” at the border to Ukraine. Click: the gallows of Kislovodsk, “against the backdrop of a scarlet evening sky — a finely etched black swing with a stub of rope,” where a “bold, gay, young, beautiful,” and “always chic” anarchist named Ksenya G was hanged.

Memories is a story of disappearance, a report on a vanishing milieu. Women clinging to their dignity make dresses out of medical gauze; landowning men refuse to help haul coal onto the Shilka, which has no crew. (“If you prefer all this socialist nonsense and labor for everyone, then what are you doing on this ship?”) Daily life is absurd, and apparel is a barometer of fortune. “We all knew that it would be impossible to buy anything when we next went ashore, so we were saving our everyday clothes for later. We were wearing only items for which we foresaw no immediate need: colorful shawls, ball gowns, satin slippers.” Horrors creep around corners: arrests, searches, shootings, torture, illness. The gray band on a black dress is revealed to be made of lice.

The book ends aboard a steamer as it sails to Constantinople. A woman wails belowdecks, and Teffi looks back across the current. “I have turned into a pillar of salt forever, and I shall forever go on looking, seeing my own land slip softly, slowly away from me.”

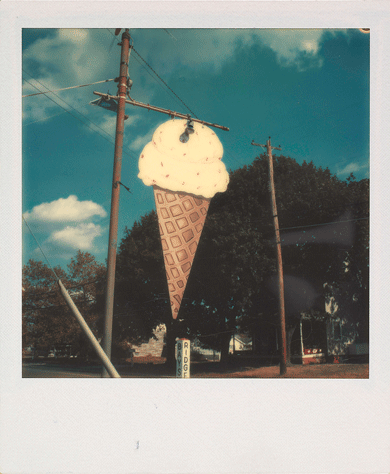

We often think about photography in the context of memory. Frozen snapshots accrue meaning over time, and we look back, as frozen as Teffi and Lot’s wife. But as Peter Buse argues in his smart and engaging THE CAMERA DOES THE REST: HOW POLAROID CHANGED PHOTOGRAPHY (The University of Chicago Press, $30), amateur picture taking was originally conceived as “a form of play.” Early advertisements for Eastman Kodak stressed “the sheer pleasure and adventure of taking photographs,” and the first mass-market camera, the Brownie, was sold as a toy. Polaroid, which debuted its Swinger in 1965, was tied to fashion, novelty, and fun. Like the nickelodeon, it is part of the history of American attractions. These were party cameras.

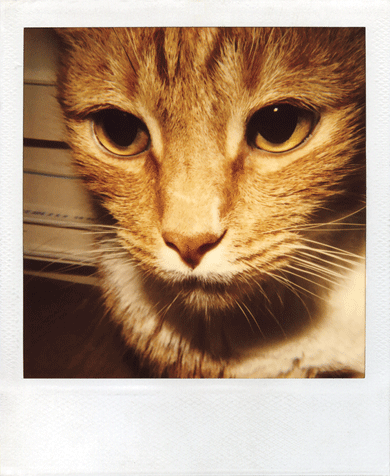

Polaroid by Walker Evans © Walker Evans Archive/The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource, New York City

Polaroid’s “prestige status was always fragile”; the company sat at the intersection of luxury and mass-market, art and utility. Whether you had a Spectra System Portfolio Gift Set from Bloomingdale’s or bought your SX-70 film at the drugstore, the appeal of the technology had as much to do with how the picture was taken as with what it looked like. The developing process invited its customers to get up close and experiment. There was a culture of scratching on Polaroids, painting on them, sticking them in toasters and freezers. Shooting a Polaroid was also an intimate act. The camera spit the image at the person who had been photographed, or held it out like a gift. (And then there were all the dirty pictures you could take in private . . . ) You could save a Polaroid in an album, but they were more likely to be cached or secreted in drawers. They carried something illicit, and precious.

The fundamental innovation of photography had to do with reproducibility: from one negative came infinite copies. Polaroid defied this. One action, one image, one object. Looking at a Polaroid is unlike looking at any other picture because a Polaroid has that which a photograph is supposed to lack: an aura. That’s not to say that there aren’t a lot of them. By 1976, there were 15 billion Polaroid pictures in existence, and that was before the cameras really caught on. The numbers are boggling, sublime. How could there be so many? Billions and billions of white-bordered, high-flash greetings. Billions and billions of faces, legs, birthday cakes. Billions of good nights and bad decisions. It’s another way to gauge time. Each shot is singular, unrepeatable; each life, a story; each image, a measure of hungry, sucking time.