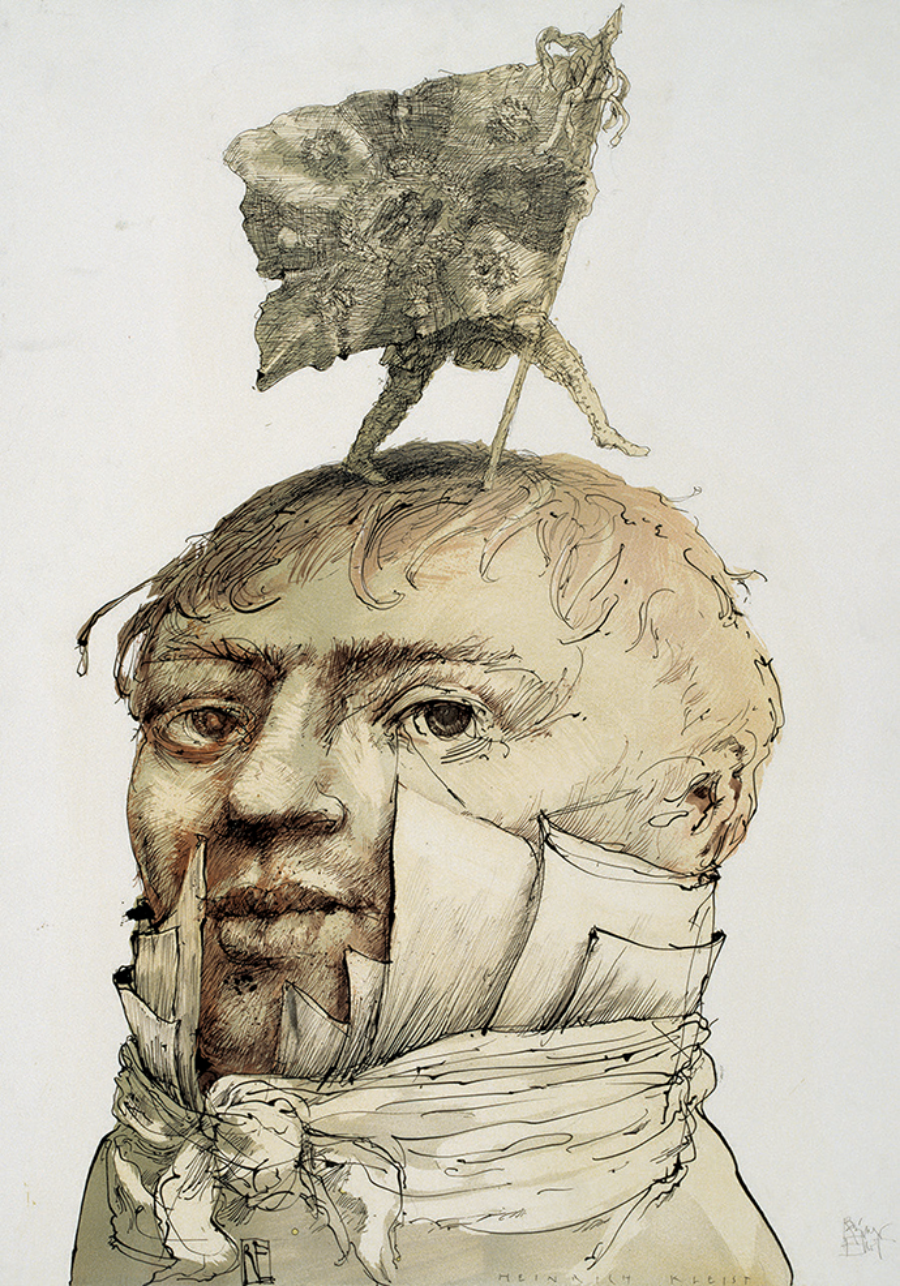

Heinrich Kleist, by Rainer Ehrt © The artist/akg-images

Discussed in this essay:

Michael Kohlhaas, by Heinrich von Kleist. Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann. New Directions. 144 pages. $14.95.

There is no cult so fervent in contemporary fiction as the cult of voice. Voice is easily confused for, but importantly distinct from, style. Where style is manufactured or arch, a mask that distances, voice, despite being performed and constructed, is a tool of immediacy and intimacy. Voice is inherently contemporary, the node of an interlocking web of other contemporary values: authenticity, personality, identity, speaking one’s truth. To encounter real literary style is almost always to encounter the past, because style itself is a remove, an art of arrangement that puts the tale and the way it is told before the person telling it. To encounter style in a time of voice can be shocking: it has the authority that our age, and our literature, reject.

In the middle of the 16th century there lived on the banks of the Havel a horse dealer by the name Michael Kohlhaas, son of a schoolmaster, at once one of the most righteous and appalling individuals of his time.

So begins Michael Hofmann’s marvelous new translation of Heinrich von Kleist’s novella Michael Kohlhaas, first published in 1810. Put it next to the first sentence of The Trial, written more than a century later, and you will see why Kafka considered Kleist one of his “true blood-relations.” Their eccentric and all-encompassing styles alter everything they touch while deflecting attention away from the narrator and toward the subject of the story. No one beginning either book could ask, Why am I reading this? You are reading it because Michael Kohlhaas was one of the most righteous and appalling individuals of his time. He is not a quiet everyman who can shed light on the issues of the day. He is the issue of the day.

The paragraph continues:

Until his thirtieth year, this unusual man would have been accounted the very model of a good citizen. In the village that still bears his name, he owned a farm that provided him with a comfortable living; the children his wife gave him he brought up in the fear of God, to be hardworking and loyal; there was not one among his neighbors who hadn’t benefited from his charity and his fair dealing; in sum, the world would have blessed his memory, if he hadn’t followed one of his virtues to excess. His sense of justice led him to robbery and murder.

Kleist’s prose is nested with clauses that move swiftly from action to action, simultaneously suggesting logic and a lack of reason; time and situations are condensed; coincidences proliferate, and events pile up like accidents. He almost never wastes time with description of a landscape or a face. There are no metaphors in the first paragraph of Michael Kohlhaas, no figures of speech—just the dispassionate accounting of existential suspense.

Kleist, a Prussian-born figure of nineteenth-century tragedy who died in a murder-suicide pact at the age of thirty-four, was the author of five feverish plays (and one fragment), a handful of essays, and eight prose stories that paired analytic rigor and restraint with plots that were shocking or even lurid. I have heard the good advice that if you dress in boring clothes, you can get away with bad behavior. But it is not correct to say that Kleist’s prose style is merely plain or reportorial, that it measures the distance between wild interior life and repressive social forms; rather, it takes the reportorial to the extreme, showing it as a form of grotesquerie. In the words of Stefan Zweig, Kleist “pushes sobriety to excess and talks to the reader through clenched teeth.” This combination of passion and soldierly reserve horrified his contemporaries. In his own lifetime he was appreciated by few, and he managed to alienate, through deed or art, those who tried to support him. In a time of rational humanism and Enlightenment optimism, he laid down in polished rows a vision of life that was chaotic and inscrutably tragic. “With the best will in the world toward this poet, I have always been moved to horror and disgust by something in his works,” wrote Goethe, “as though here were a body well-planned by nature, tainted with an incurable disease.”

The combination of “righteous and appalling” in the first sentence of Michael Kohlhaas is more appalling still because of the matter-of-fact tone. You could write the novella’s opening lines today and they would come off as a mannered pastiche. Contemporary literature does not value summation. We are not capable of or interested in condensing a life with such brutal concision, reducing it to its most essential and yet obscure movements. Today we want self-examination, autopsy, a bringing of things to light. We want to drill down into causes, locate the smoking gun, the sin of the father, the trauma. Whence came Kohlhaas’s hypertrophied virtue? To what childhood event can we trace this defect? What does being the son of a schoolmaster have to do with anything? For Kleist, “why” is irrelevant. He tells the story not because it has wisdom to offer us, but because it is a kind of sensational news report (novella means “news”) about the nature of the self. The first paragraph of Michael Kohlhaas tells us everything we will ever know; it speaks with the impersonal authority of death.

The style may be authoritative, but the world lacks some essential cohesion. In Kleist’s plays and stories, characters careen from misunderstanding to misunderstanding. Supernatural elements intervene and are hard to interpret. “The desolate loneliness of all human beings, the hopelessly opaque nature of the world and all that occurs in it,” noted György Lukács, “this forms the mood of the Kleistian tragedy, both in life and in literature.” In one story, lovers escape death in an earthquake, only to be killed by an angry mob; in another, a man who seems to lose a duel in fact wins it, when the scratch he inflicted on his enemy turns into a festering wound.

Kleist came from a long line of generals. He was born on October 18, 1777, or possibly, as he claimed, on October 10; as his biographer Joachim Maass noted, “the long list of contradictions, obscurities, and enigmas characteristic of his whole life story begins with his first day on earth.” He showed no early indication of literary greatness. As a child in Frankfurt on the Oder he made an agreement with a cousin that they would commit suicide together if “anything unworthy” should befall them (the cousin shot himself when they were teenagers). After his father’s death, Kleist was sent to Berlin to be educated; he entered the army as a corporal at the age of fifteen, but military service was not to his liking. After seven years, he was granted a discharge so that he might pursue philosophical study, the first of many decisions that disappointed his family, reduced his income, and led to his eventual estrangement from the sister, Ulrike, with whom he was closest. While tutoring some neighborhood girls in Frankfurt, he became engaged to Wilhelmine von Zenge, a daughter of a regimental commander. Wilhelmine’s parents requested that Kleist secure some suitable employment before marrying; instead, he decided to travel.

Of Kleist’s lifelong peregrinations, at least one of which involved him disappearing from the historical record for months, Zweig wrote, “He changed one town for another as a man in a fever changes one pillow for another.” In the course of his flight from Wilhelmine, Kleist journeyed to Würzburg, where he saw a doctor who treated him for a sexual dysfunction. The exact complaint is not known, but following the treatment, he enthused in a letter to Wilhelmine, “Then I was not worthy of you; now I am . . . Then I was tormented by the realization that I was unable to fulfill your most sacred needs, and now, now—but hush!” Some commentators believe he was impotent, but considering the intense friendships Kleist enjoyed with men, and the letters he wrote to male friends—“How often, when you were stripped to bathe in the Lake of Thun, have I looked at your beautiful body as a girl might contemplate it!” or “You brought back into my heart the age of Hellas, so that I should have liked to sleep with you!”—one wonders if desire rather than ability weren’t at issue.

While studying in Berlin, he suffered what is known as the “Kant crisis,” concluding, as he wrote to Wilhelmine, that “we cannot determine if what we call truth is really truth or whether it only seems so . . . My sole, my highest goal has been destroyed, I no longer have one.” The meaning of this crisis is difficult to parse, but what matters most for the reader is, as the critic Robert Helbling put it, Kleist’s “general disillusionment with man’s rational powers and the reliability of ‘appearances.’ ” Kleist clung to the idea that people could survive the deceitfulness of reality with “an indestructible inner bond” whose currency was absolute trust. In his work, this trust regularly fails. In his life, he forsook marriage as one such bond, while regularly beseeching one friend or another to commit the ultimate act of trust and end their life with him.

In 1801 in Paris—a city he detested for its frivolity—Kleist accepted his incapacity for “any conventional relationship to the world” and began to write his first play, The Schroffenstein Family. Over the next ten years, he completed the small body of work that is the sum of his huge achievement. He also coedited an unpopular literary journal (in which some of his writing was first published) and, toward the end of his life, served as editor (and writer) of his own daily newspaper. For all his resistance to settling into a respectable career, he remained, in his soul, an uptight Prussian officer with a rabid hatred of Napoleon. He was detained four times on suspicion of being a Prussian spy; once he spent months under arrest, until the Treaties of Tilsit were signed. Zweig says that Kleist “inspired dislike and even repulsion,” but he seems to have been attractive to women; he was forced to find new lodgings after the daughter of one house grew too attached to him. His confidante and sponsor Marie von Kleist (a relation by marriage) called him gentle, kind, loving, and honest. In the end, Henriette Vogel, the wife of a tax collector, agreed to die with him. She had advanced uterine cancer. In 1811, he shot her and himself on the banks of the Kleiner Wannsee.

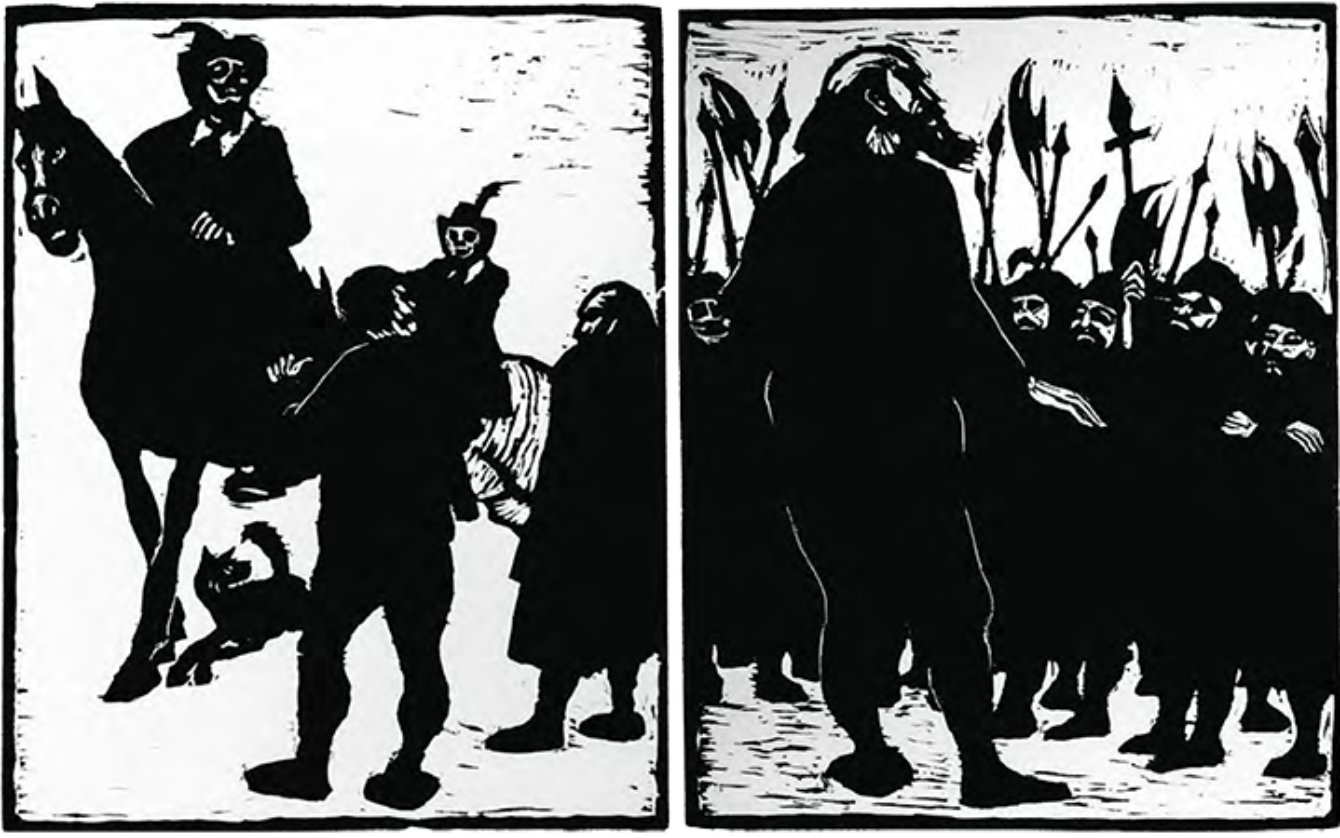

Woodcuts by Jacob Pins for an edition of Michael Kohlhaas published by the Jerusalem Print Workshop © The artist

After the opening paragraph of Michael Kohlhaas, we are presented with the key incident. While traveling from Brandenburg into Saxony on business, the titular horse dealer comes to a bridge he has crossed many times before. The former occupant of the castle overlooking the bridge has died, and the property has been taken over by a new Junker, Wenzel von Tronka. Tronka’s man demands first a fee, then a permit. Kohlhaas, attempting to meet the extortionary demands, leaves behind two fine black mares and goes into the city, where he confirms his suspicion that no permit is necessary to cross the bridge. He returns to find that his horses, and his servant Herse, have been horribly abused. The Tronkas are well connected, and Kohlhaas’s attempts to seek legal redress fail. The courts and Kohlhaas’s own lawyers advise him to fetch the horses and forget it.

Instead, Kohlhaas makes arrangements to sell his home and send his wife, Lisbeth, and children away. Lisbeth proposes to make a personal appeal to the Elector of Brandenburg on her husband’s behalf. She comes home having been injured by the butt of a guard’s lance and dies a few days later. Here is how Hofmann introduces the episode: “But of all the unsuccessful steps [Kohlhaas] had taken in his cause, this expedition was perhaps the least successful.” His is the only translation that dares to use “perhaps” in this sentence. “Perhaps” is the spirit of Kleist blazing through: the subtle, sick joke of an ostentatiously neutral chronicler.

Kohlhaas sends a letter advising Wenzel von Tronka that he has three days to return the mares and personally feed them back to health at the horse trader’s own stables. When the time expires, Kohlhaas gathers his servants, attacks the castle, brutalizes whomever he finds, and gallops off to torch several towns in search of the Junker, who escaped the rampage. Kohlhaas’s army grows, and he becomes increasingly megalomaniacal, signing edicts and decrees and, in a Protestantism run amok, rejecting all but God’s authority. Martin Luther gets involved. The powers that be offer Kohlhaas safe passage in exchange for hearing his case, whose merit they can no longer deny. Kohlhaas’s demands remain steady throughout: the return of the horses in their prior condition, financial redress for what Herse suffered and the goods he lost at Tronkenburg. Through some unfortunate events that are no fault of his own, the tide turns against Kohlhaas, and he is placed under house arrest. Eventually his case is heard and is found in his favor, his demands are met, and—icing on the cake—the Junker is sentenced to two years in prison. Kohlhaas, whose “deepest wish on earth had been satisfied,” is executed for his crimes against the state.

No translation could ruin Michael Kohlhaas, whose interest is so much in the dramatic piling on of ever more outrageous events. But Hofmann makes many choices that, in the aggregate, give us a sharper and more stylish book. His improvements begin with the first sentence. Where previous translators of Kleist have rendered the original rechtschaffen as “upright,” “fair-minded,” or “honorable,” Hofmann gives us “righteous,” emphasizing not any particular virtue, but the idea that Kohlhaas is inherently just. More significantly, where previous translators give entsetzlich as “terrible,” Hofmann chooses “appalling.” He foregrounds the public’s reaction to Kohlhaas, and the reader’s to Kleist, rather than the character’s internal contradictions. The meaning of the story is thus clarified: not to pass a judgment on the rightness or wrongness of the actions, but to be provoked by them, to feel awe, dread, dismay, and wonder at the transformation of respectable virtue into terrorism.

In Kohlhaas as in his other stories, Kleist indicates rich subjective complexity but insists on remaining on the objective ground of plot or event. He writes characters who are, in Helbling’s words, “condemned” to be themselves; who battle “to achieve personal coherence,” but whose battle excludes understanding, for themselves or the reader. The reason that attempts to film Michael Kohlhaas have failed so resoundingly is that directors try to fill in the background with pointless “lifelike” mise en scène, and actors vainly attempt to animate the characters, to inhabit what is only expressive. (In his essay on marionettes, Kleist admired the way that a lack of self-consciousness makes a wooden puppet dance more gracefully than a human. A puppet never “strikes an attitude”; it moves, dead and without striving, from its center of gravity.) On YouTube there is a ten-minute video of Michael Kohlhaas performed by Playmobil action figures, and for all its silliness it is true in spirit to the novella, because it emphasizes action over character and is accompanied by a breathless voice-over. Kohlhaas is a story to be told and heard rather than seen. (Kafka urged Felice Bauer not to read it herself, because he would read it to her.) Éric Rohmer succeeded in filming Kleist’s Marquise of O because he found an appropriately rigorous style—minimal camerawork, static shots, a purposefully theatrical presentation, and characters whose actions seem outwardly determined rather than internally motivated.

The two major literary homages, J. M. Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K and E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, don’t shed any particular light on Kleist—they use Kleist in the way of a prompt, to get somewhere else. (Is there something about Kleist, that he attracts men who go by their initials?) Coetzee respected the unknowability of Kohlhaas’s nature while making his own desire to know more part of his book’s plot. But understanding that the character of K is connected to Kohlhaas is extra credit; it doesn’t fundamentally change the experience or meaning of the text. Doctorow turned Kohlhaas into Coalhouse Walker Jr., an African-American man who is a victim of a racist attack. But by explaining so much, Doctorow explained away. It is important that at no point can we say, while reading Kleist, “Well, torching Leipzig was the next best step; I see how I, too, would do it.” Kohlhaas is not a representative figure of revolution but a man in the grip of his temperament, similar to the eponymous protagonist of Kleist’s tragedy Penthesilea. In that play, when a priestess asks why the Amazonian queen Penthesilea doesn’t flee her battle with Achilles when there is “no external / force to hold her here, no hand of fate, / but only her own foolish heart—,” another character interrupts.

But that’s

her fate! You think iron bands can’t

be ripped apart, am I right? But still,

it’s not

outside the realm of possibility

that she should break such bands—

yet not the feeling

you deride.

I began by opposing the style of Kleist to the voicey narrators of contemporary fiction. But we might say that today’s writers depart from the same place as Kleist—from a suspicion about what it is possible to say about the world. Today we no longer believe it is possible or worthwhile to speak about the world except insofar as we experience it partially, let alone to speak about or on behalf of other people. Our answer is to reveal, revel in, or further obscure the self. Kleist, who also doubted appearances, who also eschewed a belief in progress, took a different path. It was, as Zweig put it, his “fiendish delight to force others to accompany him into a region of intense sensations” on the page. What he was after, wrote Thomas Mann, was “a ‘confusion of affects.’ This holds true even of his most charming and delightful version of Molière’s Amphitryon.”

Amphitryon is—what else to call it?—a rape comedy, not the only one that Kleist wrote. In it, the god Jupiter disguises himself as Amphitryon in order to sleep with Amphitryon’s wife, Alcmene; much of the play concerns her being confused over whom she slept with, and then grilled by Jupiter on who is a better lover. (He is.) Kleist offended the readers of his literary journal with The Marquise of O, which begins with a Russian count heroically saving the Marquise from a sexual assault. Some time later she begins to suspect she is pregnant, but does not know how it could have occurred. The count returns and insistently proposes to her; the Marquise, unsuspecting, says no; when the pregnancy becomes undeniable, she puts a notice in the paper asking the father of her unborn child to come forward. In the end, it is revealed that the very count who was her “angel” was also her “devil,” taking advantage of a fainting spell that overcame her after the interrupted assault. She marries him grudgingly, but over time they fall in love and have more children together.

Commentators on Kleist have the unfortunate habit of describing the Marquise as being “impregnated in her sleep”; Coetzee at least uses the word “rape,” but doubts the Marquise’s guilelessness, asking, “Is it possible not to know whether one has had sexual intercourse?” A stranger lacuna in the criticism occurs regarding “The Betrothal in Santo Domingo.” This story concerns Toni, a fifteen-year-old mixed-race Haitian teenager who helps her mother and other black revolutionaries entrap and kill whites. One night a white man named Gustav comes to their home looking for help. He and Toni have a sexual encounter that leads to their engagement and causes Toni to identify herself as white. Although Toni tries to save Gustav, he suspects her of betraying him and kills her. When he realizes his mistake, he kills himself. On the one hand, it’s a love story; on the other, we are left with the strong impression that Toni has been raped into whiteness.

What happened next need not be told, since everyone who gets to this point in the tale can guess. Rousing himself afterwards, the stranger had no idea where the impetuous thing he’d done would lead him . . . Seeing her lying there on the bed with her arms crossed beneath her, crying her eyes out, he did his best to try and comfort her.

Kleist uses violence—specifically sexual violence—as an epistemological tool, one that withholds or grants vital knowledge related to one’s identity. He understands knowledge not as an ennobling good, but as a catastrophe of desire that befalls the powerless.

Here is how Kohlhaas ends: We learn, more or less out of nowhere, that the horse-dealer has for a long time been wearing around his neck a scrap of paper that was given to him, a few days into his campaign of terror, by a fortune-teller who strongly resembled his dead wife. This paper reveals the manner in which the Elector of Saxony will lose his hold on power. When the Elector realizes that Kohlhaas is in possession of this knowledge, he offers Kohlhaas, who has been sentenced to death, his life in exchange for the paper. Kohlhaas refuses. The Elector’s aide hires a beggar woman to pretend to be the fortune-teller and attempt to extract the paper, but the beggar woman turns out to be the actual fortune-teller. The fortune-teller, who we now understand to be the incarnation of Kohlhaas’s dead wife Lisbeth, urges him to think of the children and use the paper to save his life. But Kohlhaas is by now “jubilant at the power that had been given him to wound his enemy mortally in the heel even as he made to trample him in the dirt.” When he glimpses the Elector in the crowd at his execution, he rips off the necklace, reads the paper, swallows it, and wordlessly submits to his beheading.

Most readers do not overly admire this series of events. Kleist’s biographer Maass complained that “the hard logic of the plot is diluted by this excursion into the irrational.” Even Kafka, who adored the story, called the ending “rather weak, in part carelessly written.” As much as it pains me to be on the wrong side of Kafka, I think it’s a great ending, for it hammers on what Michael Kohlhaas is all about. This is not a story about the obligations of the state to the individual or the making of a terrorist or a theory of justice. This is a story about the transformation of righteousness into spite. Kleist produces a miracle, a chance at salvation, only so that his hero can reject it. Kohlhaas is kin to the merchant Piachi, who, in Kleist’s story “The Foundling,” refuses absolution at the gallows:

I do not want to be saved, I want to go down into the deepest pit of hell, I want to find Nicolo again—for he will not be in heaven—and continue my vengeance on him which I could not finish here to my full satisfaction.

“For Kleist and for the people Kleist created,” Lukács noted, “death is an omnipresent abyss that is both enticing and at the same time makes the blood run cold.”

And so we come to Kleist’s own end, the infamous murder-suicide. “The decision that flared up in her soul to die with me has drawn me—with what ineffable and irresistible force!—to her bosom,” Kleist wrote of Vogel, to Marie von Kleist. “Do you remember that I have several times asked you to die with me?—but you always said no.” This man who, it is likely, never had a fully consummated romantic relationship, was all his life drawn to death but unwilling to die alone. What is the meaning of such a fixation? Was it power over another he sought, or absolute kinship of the soul? Suicide is hardly a hero’s exit, but in the planning of his death Kleist seems to have found the camaraderie and sympathy that so eluded his characters. “May the heavens give you a death even approaching mine in joy and ineffable serenity,” he wrote to his sister Ulrike. “That is the most fervent and heartfelt wish that I can summon up for you.”