In Havana, the past year has been marked by a parade of bold-faced names from the north — John Kerry reopening the United States Embassy; Andrew Cuomo bringing a delegation of American business leaders; celebrities ranging from Joe Torre, traveling on behalf of Major League Baseball to oversee an exhibition game between the Tampa Bay Rays and the Cuban national team, to Jimmy Buffett, said to be considering opening one of his Margaritaville restaurants there. All this culminated with a three-day trip in March by Barack Obama, the first American president to visit Cuba since Calvin Coolidge in 1928. But to those who know the city well, perhaps nothing said as much about the transformation of political relations between the United States and Cuba that began in December 2014 as a concert in the Tribuna Antiimperialista.

The arena, which sits next door to the U.S. Embassy, was long the venue for strident anti-American demonstrations. After the revolution, the embassy building was formally taken over by the Swiss, who hosted the U.S. Interests Section of the Embassy of Switzerland — the de facto U.S. embassy before the reestablishment of diplomatic relations. The area around the Tribuna and the Interests Section became the site where the U.S. and Cuban governments were most openly derisive toward each other. In 2004, the Interests Section posted a ten-foot sign emblazoned with 75, the number of political dissidents who had been arrested by the Cuban government the previous year. Cuba responded by putting billboards around the Interests Section with graphic images of U.S. human-rights violations at Abu Ghraib. The Interests Section later mounted a digital ticker along the fifth floor of its building, with five-foot-tall LED letters visible to everyone driving along the Malecón, the seaside highway that runs along much of Havana. The ticker streamed messages about freedom and democracy, rising up against slavery and overthrowing oppression — a less-than-subtle encouragement of antigovernment activity. Cuba then installed 138 posts flying immense black flags in front of the building. The number was said to represent the Cuban deaths attributed to the U.S. government — ranging from Bay of Pigs casualties to the victims of terrorists such as Luis Posada Carriles, a Cuban exile convicted in the bombing of Cubana flight 455, which killed seventy-three people.

After President Obama took office, the billboards started coming down and the ticker quietly went dark. And two weeks before Obama’s arrival, in one of the most telling expressions of optimism and hospitality, the Tribuna Antiimperialista — against the backdrop of the newly reopened embassy — hosted a free concert by the electronic-music trio Major Lazer. Some 400,000 Cubans filled the Malecón to see three Americans play exuberant dancehall music.

When I spoke to friends and colleagues in Havana at the time, the hope and excitement was palpable. But there was also considerable anxiety about Cuba’s future. Most Cubans have seen little improvement in their economic opportunities since the thawing of relations began. Food prices rose dramatically last year, and there has been limited improvement in the availability, or the affordability, of consumer goods. Amid the festivities and the flood of celebrities, it would be easy for Americans to miss that the central plank of the long-standing cold war against Cuba — the economic embargo — remains very much alive and well.

In the American imagination, the embargo serves mostly to deny us access to Cohibas and Havana Club rum, but its damage to the Cuban people has been, and continues to be, pervasive and profound. It affects their access to everything from electricity to video games to shoes. It has prevented Cubans from buying medical supplies from American companies, from buying pesticides and fertilizer, from purchasing Microsoft Word or downloading Adobe Acrobat. It has restricted how much money Cuban Americans can send to their families on the island. Americans have been prosecuted for selling water-treatment supplies to Cuba and threatened with prosecution for donating musical instruments. Unlike federal regulations, which can be changed by executive decree, the embargo’s most severe and far-reaching provisions are based on a patchwork of legislation that only Congress can repeal, something it has given no sign that it plans to do.

The embargo — which Cubans call el bloqueo (“the blockade”) — has been in place since 1960. It was initially imposed because of Cuba’s ties to the Soviet Union. After the Soviet Union’s fall, it was rationalized as a punishment for Cuba’s support for revolutionary movements elsewhere in Latin America. But that support ended years ago. Since then, the embargo has mostly been framed as a response to human-rights violations by the Cuban government.

Outside the United States, however, the embargo itself is widely seen as flouting international norms. Every year, Cuba introduces a resolution to the U.N. General Assembly, maintaining that the embargo contradicts the U.N. Charter. In 1992, fifty-nine countries supported the resolution, while the United States, Israel, and Romania opposed it, and the rest of the member states abstained. Support has grown steadily each year since. Last fall, the vote was 191 to 2 — that is, apart from the United States and Israel, every country in the United Nations believes that the embargo is illegal and has joined with Cuba in denouncing it.

Most Americans have views along the same lines: according to the Pew Research Center, nearly three quarters of Americans support lifting the embargo. This includes such Cuban-American hardliners as the sugar magnate Andres Fanjul, billionaire Mike Fernandez, and Carlos Gutierrez, the secretary of commerce under President George W. Bush. Even many of the most prominent anti-Castro dissidents, such as Vladimiro Roca, a human-rights activist, and Juan Carlos Cremata, a filmmaker, have called for an end to the embargo — ironically, in interviews with Radio Martí, a broadcast funded by the U.S. government.

Although in many ways Cuba is a highly developed country — there is nearly 100 percent literacy, and the infant-mortality rate is comparable to that of the United States — it is also very poor. Housing is perennially scarce, and consumer goods are difficult to obtain. In Havana, a city of 2 million people, there is an astonishingly small number of stores, and their goods are often limited in selection, cheaply made, and very expensive. On any given day, you could scavenge every store in Havana looking for Scotch tape, dental floss, or lightbulbs, and simply find none, anywhere.

Much Cuban conversation involves the word “resolver” — to find a workaround when every solution is expensive, circuitous, or illegal. For most Cubans, daily life for the past quarter-century has been consumed by resolviendo the continual problems of educating children in the absence of paper and pencils; repairing a roof or a toilet without tools or materials; or looking for a distributor cap and spark plugs for one’s 1985 Lada, a Fiat manufactured in the Soviet Union, when there was a Soviet Union.

During the Cold War, the effects of el bloqueo were quite limited. Cuba traded with the Soviet bloc on generous terms, benefiting from oil subsidies and exchanging sugar for everything from tractors to canned goods, which largely compensated for the lack of access to U.S. markets. Cubans remember the Eighties as a period of economic security, if not quite prosperity. The libreta — the ration book — provided beans, rice, cooking oil, eggs, laundry detergent, soap, even gasoline and cigarettes, at highly subsidized prices. Schools and medical clinics had enough supplies to meet the needs of students and patients. At the same time, there was a parallel market where Cubans could easily afford to buy bread or milk, as well as the occasional leg of lamb.

During the Cold War, the effects of el bloqueo were quite limited. Cuba traded with the Soviet bloc on generous terms, benefiting from oil subsidies and exchanging sugar for everything from tractors to canned goods, which largely compensated for the lack of access to U.S. markets. Cubans remember the Eighties as a period of economic security, if not quite prosperity. The libreta — the ration book — provided beans, rice, cooking oil, eggs, laundry detergent, soap, even gasoline and cigarettes, at highly subsidized prices. Schools and medical clinics had enough supplies to meet the needs of students and patients. At the same time, there was a parallel market where Cubans could easily afford to buy bread or milk, as well as the occasional leg of lamb.

That abruptly came to an end with the fall of the Soviet Union, when 85 percent of Cuba’s trade evaporated overnight. The government responded to this crisis by rapidly restructuring the economy and reaching out to new trading partners. It rejuvenated Cuba’s tourism industry with investment from the Spanish hotel chain Meliá; developed nickel mining in partnership with the Canadian resource company Sherritt; and built on the country’s strength in biomedical sciences, ramping up development of biotechnology and pharmaceuticals.

Two years into this recovery effort, the U.S. Congress passed the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992, introduced by Robert Torricelli, a congressman from New Jersey, and signed into law by President George H. W. Bush. Among other things, the act extended the reach of the embargo by applying it to foreign-based subsidiaries of American companies, entities that international law views as nationals of the countries in which they are incorporated. The law effectively imposed American control over foreign companies doing business with foreign countries, an act of “extraterritoriality” that was harshly criticized by the international community.

In 1996, Congress added the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, sponsored by Senator Jesse Helms and Congressman Dan Burton. This tacked on further extraterritorial provisions, such as exposing foreign companies to lawsuits in U.S. courts for using any property in Cuba that had once belonged to Cuban landowners who were now U.S. citizens. In response, Canada and other U.S. allies passed retaliatory “clawback” legislation, and the European Union brought action against the United States before the World Trade Organization.

As Cuba developed new initiatives to revive its economy, the embargo targeted each in turn. This included Cuba’s leading exports: nickel and sugar. Nickel is used in the manufacture of stainless steel, and Cuba is among the world’s largest producers. The Helms–Burton law makes it illegal to export any metal object to the United States if it contains even trace amounts of Cuban nickel. The same is true of sugar — any company that sells candy in the United States may not include even tiny amounts of Cuban sugar in its products. In effect, the embargo means that any company that wants to do business in the United States has to boycott Cuba, or lose access to American markets themselves.

In the late 1980s, Cuba invested heavily in biotechnology, establishing more than fifty research centers in areas ranging from biopesticides for agriculture to medical and pharmaceutical products addressing diseases found in the developing world. The burgeoning industry was viewed with great pride in Cuba, and was becoming increasingly important to the economy. So the Cuban Democracy Act specifically prohibited U.S. companies from exporting to Cuba any equipment or materials that could be used in marketing or developing Cuba’s biotech products.

This double blockade — the end of Soviet patronage combined with the tightening of the U.S. embargo — was devastating. Cuba had few funds available to buy fuel, inputs for agriculture and industry, or equipment to maintain infrastructure. Without gasoline or repair parts, tractors were replaced by oxen. City buses disappeared, and thousands of Flying Pigeon bicycles were imported from China to provide public transportation. Cuba struggled to increase crop yields without the pesticides and fertilizers that were now unaffordable. For the first time in many years, there were serious food shortages. Potatoes, vegetables, and pasta were taken off the libreta; soon after, even such basic staples as beans and rice were not always available. Some of Cuba’s economic problems were rooted in the sluggishness of its bureaucracy and the state’s ambivalence about implementing economic reforms. But the embargo also had a huge impact.

The worst years of the economic crisis, from 1990 to 1995, were a time of profound desperation. Young women with university degrees turned to prostitution. A colleague told me that she had traded a pair of shoes on the black market for a piece of chicken for her elderly mother. At the home of a friend, a five-pound bag of tomatoes was the only food for a family of three adults, for two days. There were rolling blackouts throughout Havana. Families could go without electricity for days at a time; they might wait until midnight for the cooking gas to come on or wait most of a week for water to run through the pipes. Living in a twenty-five-story building became a nightmare when there was no power to run the elevators.

The hardship became a source of dark humor. “Did you hear about Luis?” a friend asked me. “He had arranged to swap apartments with a neighbor, when the neighbor’s elderly father passed away. The father died during a blackout, and Luis had to help the neighbor move the body. They couldn’t use the elevator, so Luis and the neighbor had to carry the father’s body down fourteen flights of stairs, in the dark, trying not to drop it.”

The worst of the crisis ended in 1995, but the embargo undermined Cuba’s efforts to develop new markets, find partners for joint ventures, and establish new trade links. Meanwhile, infrastructure continued to deteriorate. In 2004, there were fewer buses in Havana than there had been a decade earlier. Gasoline was unaffordable for most people; no one could get spare parts or do any sort of decent repairs on trucks or cars. On annual research trips to Havana, I saw motorcycles with sidecars being used as delivery vans; two men loading a washing machine onto a bicycle taxi; and ancient, enormous Chevys from the Fifties, called boteros, driving up and down the main streets, offering rides to Cubans for ten pesos each. Tourists would take pictures, chuckling and marveling at Cuban ingenuity. In reality, these were desperate attempts to compensate for an urban transportation system’s near-complete collapse.

Partly in response to international criticism of the humanitarian impact of the embargo, Congress passed the Trade Sanctions Reform and Export Enhancement Act in 2000, which permitted U.S. companies to sell food to Cuba. But the T.S.R.A. permitted even those sales only on adverse terms. When Cuba buys food from American companies, it must pay in cash, and in advance — punitive terms for a cash-strapped country. This means that buying food effectively worsens Cuba’s debt crisis.

While the core of the U.S. embargo is statutory, regulations provide its machinery, and the administration has considerable discretion to shape them. Thus, the president can do a good deal to mitigate the embargo’s effects — or exacerbate them. In 2004, the Bush Administration severely cut — from $3,000 to $300 — the amount of money Cuban Americans could bring to family members when they visited Cuba. Bush also implemented a three-year rule: Cuban Americans could visit their family on the island only once every three years; no exceptions were made even for humanitarian need, such as the death or illness of a loved one. When Cuban Americans did travel to Cuba, they could spend only $50 a day.

Soon after taking office, President Obama lifted the three-year rule and permitted American travelers to spend about $170 per day in Cuba, which was at least enough for a hotel room and meals. But most of the other restrictions remained in place until this year, and while the Bush Administration was more bellicose in tone toward Cuba, the Obama Administration actually enforced the embargo much more aggressively for most of its tenure. One set of regulations, the Cuban Assets Control Regulations, is enforced by the Treasury Department. These rules affected all of Cuba’s international transactions. Cuba could not buy or sell anything in U.S. dollars, and Cubans could not have bank accounts denominated in dollars, the global reserve currency. If a foreign bank opened an account or executed a wire transfer for a Cuban national, it was subject to massive fines by the Treasury Department. For most of his presidency, Obama kept these rules in place. The Treasury Department has only recently authorized American banks to open accounts for Cuban nationals and to process so-called U-turn transactions for Cuba, in which both parties to the sale are outside U.S. jurisdiction. Yet foreign governments and companies remain wary, as the legal boundaries of these reforms have not been tested and the next president could decide to roll them back in six short months. Most American banks and financial companies continue to be reluctant to have any dealings with Cuba, citing the sanctions.

There is no question that the Obama Administration and the Cuban government have done much to normalize U.S.–Cuban relations since the accords of 2014. There have been talks to develop more cooperation between Washington and Havana on counternarcotics efforts, environmental practices, the prevention and treatment of transmissible diseases, and migration. Last December, the two countries announced a pilot program for direct postal service. While in Cuba, Obama announced that the “100,000 Strong in the Americas” project — which aims to encourage student exchange between the United States and the rest of the Western Hemisphere — will be available to Cuban universities. In the future, scholarships and educational grants will also be available to Cuban students.

There is no question that the Obama Administration and the Cuban government have done much to normalize U.S.–Cuban relations since the accords of 2014. There have been talks to develop more cooperation between Washington and Havana on counternarcotics efforts, environmental practices, the prevention and treatment of transmissible diseases, and migration. Last December, the two countries announced a pilot program for direct postal service. While in Cuba, Obama announced that the “100,000 Strong in the Americas” project — which aims to encourage student exchange between the United States and the rest of the Western Hemisphere — will be available to Cuban universities. In the future, scholarships and educational grants will also be available to Cuban students.

Along with the reestablishment of diplomatic relations, one of the most important developments has been the State Department’s removal of Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. While not strictly part of the embargo, the terrorism designation deeply affected Cuba’s ability to do business. The State Department added Cuba to the list in 1982 because of its alliance with the Soviet Union. Up until last year, the designation persisted on the grounds that Cuba provided a safe haven to Basque separatists and Colombian rebels. Even though it had been many years since Cuba actively supported revolutionary movements, many companies, especially banks, were hesitant to do business with the country when it was on the terrorism list, forcing Havana to pay higher prices and to deal with questionable business partners. The removal of Cuba from the list has made international companies more comfortable conducting trade.

The regulatory changes make life easier in other ways for the U.S. enterprises allowed to do business in Cuba, which can now hire staff and have storefronts, warehouses, and offices. There have also been a number of modifications to U.S. regulations, though they fall far short of ending the embargo. Many of them only reverse the harsh measures imposed by the Bush Administration more than a decade ago, in effect restoring the terms that were in place during the Clinton era, such as increasing religious visits and educational trips. While such measures contribute to normalizing relations, none of them will help Cuba’s economy as much as one significant change: Cuban Americans can now send as much money to their families in Cuba as they would like. Family remittances, estimated to total about $2 billion each year, are a major source of revenue for the Cuban economy.

The T.S.R.A. still prohibits American tourism to Cuba, which is defined as any travel outside of family visits, journalism, religious activities, and professional research. But travel to Cuba has become much easier for U.S. citizens fitting these categories. Until this year, most eligible travelers had to apply for a specific license, a process that typically took months. The Treasury Department was often vague about what it required in order to grant the license, so churches, universities, or nonprofit organizations had to submit applications again and again, sometimes providing hundreds of pages of documentation, only to have the license denied the week before the trip. Other kinds of travel needed only general licenses, which were simply an authorization of travel, without requiring a specific application in advance. At different points in recent years, there were general licenses for academic researchers, full-time professional journalists, and Cuban Americans visiting family members. Perhaps the most significant change the Obama Administration made in regard to travel limitations was that several of the categories that had required specific licenses are now allowed to travel under a general license. A church group going to Cuba for religious activities must still comply with the regulations, but now it can travel without applying in advance. The same is true for people-to-people educational trips. Organizations can bring a group to see Cuban art, for example, without having first to obtain the approval of the Treasury Department for planned meetings and events on their itinerary. And in March, the regulations were loosened further to allow individuals to travel on educational trips.

As a result of these changes, the number of Americans visiting Cuba in 2015 reached 161,000, a 77 percent increase from the previous year, which does not include the estimated 400,000 Cuban Americans who made family visits. Marazul Charters, one of the major U.S.-based agencies handling Cuba travel, reported an increase of another 45 percent (not including family travel) as of this April, in addition to a 15 percent rise in foreign visitors. (Travelers from the United States still make up only a small portion of Cuba’s international visitors, which hit a record 3.5 million in 2015.) The United States and Cuba have also signed an agreement to start operating commercial flights between the two countries. More than a dozen U.S. companies are vying for approval for 110 daily flights.

The new regulations also allow Americans to use credit cards in Cuba, at least in theory. This would make travel far easier and more secure. The embargo long prohibited wiring money, sending traveler’s checks, or sending currency in any other form, so American travelers have had to carry cash for everything they buy, and for any emergencies. For a class of college students visiting Cuba for a week, their instructor would need to bring $10,000 or $15,000 in cash to pay for meals and expenses. The possibility of using credit cards would not only make life much easier for American travelers but would increase Cuba’s retail sales considerably. This new development, however, is of little use as yet, since Cuba lacks the infrastructure to collect payment on credit-card purchases.

For all this, most components of the embargo remain well in place. U.S. statutes still require officials to actively block Cuba’s membership in or access to the major international financial institutions — including the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank. The United States continues to withhold part of its dues to the United Nations in order to compromise funding for U.N. programs operating in Cuba. And any medical export to Cuba’s public-health system still requires on-site verification of its proper use, making medical sales virtually impossible.

But one of the most significant difficulties is the chilling effect of the Treasury Department’s enforcement, which has continued to be very aggressive this year. Two foreign subsidiaries of Halliburton paid penalties for their oil-drilling work with Cuba Petróleo in 2011. CGG Services, a French company, paid a $600,000 penalty for providing equipment in 2011 to vessels that were operating in Cuban territorial waters. A British company paid $140,000 in fines for providing design services in 2010 for a hotel project on a small resort island off the Cuban coast. Even though President Obama has announced a new era of increased openness and trade, the recent prosecutions — for relatively small violations that took place years ago — make international companies wary of doing business with Cuba.

Meanwhile, Cuba is doing what it can to strengthen its economy. In 2014, the government approved a law to dramatically reduce taxes for foreign investors and streamline the approval process for new projects. In 2014 and 2015, the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Investment announced more than 350 new investment opportunities, totaling some $8 billion, in areas ranging from tourism and construction to health care and renewable energy. Brazil has been a major investor in the development of the port of Mariel as a shipping hub and economic-development zone. Last December, Cuba reached an agreement with fourteen creditor countries in the Paris Club to forgive $8.5 billion of its $11.1 billion debt. In March, after two years of negotiations, the European Union adopted a common position to normalize relations with Cuba and lay the groundwork for expanded trade.

Cuba’s economy, however, is still struggling. Runaway inflation has led to the return of price controls on some staples. Cuba has seen an average annual growth of less than 3 percent for the past five years. Venezuela, which had been a major trading partner and investor, is facing its own political and economic difficulties, and is unlikely to continue offering Cuba aid. None of the changes introduced by President Obama can reverse the congressional legislation that prohibits the direct or indirect sale of most Cuban products to U.S. buyers and prohibits the sale of most goods to Cuban state enterprises. While Cuban Americans send more funds to their families on the island, and there are some circumstances under which it is possible for Americans to invest in small private businesses, these will not generate direct revenue for the government, which still employs 75 percent of the workforce and provides education, medical care, and most of the population’s housing.

“This is a new day — es un nuevo día — between our two countries,” President Obama announced in March to journalists assembled at the Plaza de la Revolución. But for all the improvements in U.S.–Cuban relations over the past two years, that new day will not really come until the embargo is lifted in its entirety. “We Cubans want this story to end,” one woman, who runs a guesthouse in Havana, told me during my most recent trip. “The conflict is senseless.”

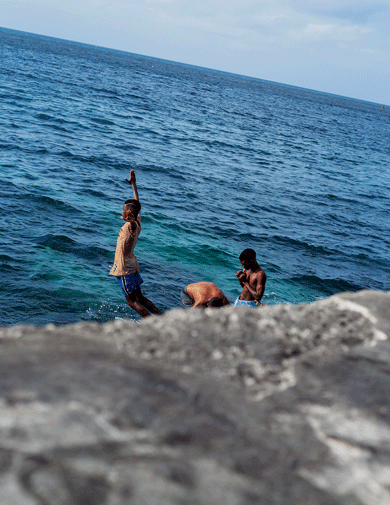

Certainly the embargo has left deep scars. It has continued for more than half a century, doing its worst damage at times when Cubans were at their most vulnerable, with aggressive enforcement that in critical ways continues to this day. Yet Cuba remains a remarkable place. In Havana, the buildings may be in a terrible state of repair, but in many ways the city is quite beautiful. If Americans could travel freely to Cuba, they might find that there is no better way to spend an evening in Havana than sitting in the lush tropical garden behind UNEAC, the union of artists and writers, sipping rum and listening to a concert of boleros. They may find themselves thinking that there is no fruit sweeter and more delectable than the spotted yellow mango, after the first rains have come. They may discover that there is no place more spectacular to be at dawn than on the Malecón, watching the sun rise behind Morro Castle.