Discussed in this essay:

Aeneid Book VI: A New Verse Translation, by Seamus Heaney. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 112 pages. $23.

He was, to borrow Yeats’s phrase, the “smiling public man,” who sat with, and was quoted by, world leaders; the recipient of a Nobel and nearly every other prize; and the author of some of the most important and admired poetry of the past half-century. At the same time, he was a beloved father figure — an exemplar and encourager — to generations of Irish, British, and American poets and critics, not to mention writers, translators, and publishers in many other countries, from Poland and Italy to China and Mexico — where his collected poems have just been published. The death of Seamus Heaney, in 2013, left the literary world unmoored and unroofed.

In addition to his three essay collections and twelve books of poetry, Heaney produced many translations. For the stage, he remade Sophocles’ Antigone into The Burial at Thebes (2004) and, earlier, his Philoctetes into The Cure at Troy (1991), to which he added the oft-quoted chorus: “Once in a lifetime / The longed-for tidal wave / Of justice can rise up, / And hope and history rhyme.” He translated Diary of One Who Vanished: A Song Cycle by Leoš Janácek of Poems by Ozef Kalda (2000) from the Czech and Robert Henryson’s The Testament of Cresseid (2004) from the Middle Scots. In a long interview with Dennis O’Driscoll (published in 2008 as Stepping Stones), Heaney downplayed his knowledge of these source languages. His version of the medieval Irish work Sweeney Astray (1984) involved, he claimed, an initial encounter that “was more with the English on the right-hand page” of an earlier bilingual edition “than with the original on the left.”

Translation became a “pleasure and joy” for Heaney (“You get the high of finishing something you don’t have to start”), but it was also a means of oblique political commentary or apologia. The lesser-known stanza that precedes the hope-and-history chorus from The Cure at Troy, for example, talks of hunger strikers and police widows, drawing an explicit parallel between the Troubles in Northern Ireland and civil strife in ancient Troy. In “An Afterwards,” from Field Work (1979), the speaker’s wife condemns “all poets” to the ninth and last circle of hell, where, as “a rabid egotistical daisy-chain,” they will feed off one another’s heads, “like Ugolino on Archbishop Roger” — a reference to the passage from Dante’s Inferno that Heaney translated for the same book:

I walked the ice

And saw two soldered in a frozen hole

On top of other, one’s skull capping the other’s,

Gnawing at him where the neck and head

Are grafted to the sweet fruit of the brain,

Like a famine victim at a loaf of bread.

Heaney said that the passage about Ugolino — who starved to death in jail after betraying the city of Pisa — was meant “to be read in the context of the ‘dirty protests’ in the Maze prison,” in which members of the I.R.A. refused clothing and smeared excrement on the walls of their cells to protest their status as criminals and not political prisoners.

Heaney’s book The Midnight Verdict, which collects his translations of Ovid and the eighteenth-century Irish-language poet Brian Merriman, was in part a response to the critical mauling Heaney and his coterie of male editors received from feminists for their Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (1991), which included very few women. In “The Death of Orpheus,” his version of the opening of Metamorphoses Book XI, the protagonist is playing his lyre when “one of them whose hair streamed in the breeze / Began to shout, ‘Look, look, it’s Orpheus, / Orpheus the misogynist.’ ” A gang of women chase the poet until they catch him and rip him limb from limb.

Heaney’s latest, and presumably final, translation seems less political than personal. According to his preface, Aeneid Book VI is “neither a ‘version’ nor a crib.” Rather, it is “more like classics homework, the result of a lifelong desire to honour the memory of my Latin teacher at St. Columb’s College, Father Michael McGlinchey.” As Heaney explains:

The set text for our A-level exam in 1957 was Aeneid IX but McGlinchey was forever sighing, “Och, boys, I wish it were Book VI.” Over the years, therefore, I gravitated towards that part of the poem and took special note of it after my father died, since the story it tells is that of Aeneas’ journey to meet the shade of his father Anchises in the land of the dead.

The new translation feels like an appropriate coda to his life’s work, not only because Book VI is where Virgil deals with the underworld, with grief and death, but also because it contains many of the motifs and themes that fed Heaney’s imagination over the course of his career.

Heaney was a poet of thresholds, limits, and boundaries. Right from the start, with “Digging,” which opens his first book, Death of a Naturalist (1966), he signaled his intent to unearth the unseen with his pen and examine the present in the light of the past. Many Heaney-objects and Heaney-places — wells, pumps, caves, bogs — are concerned with transitions. His poems often involve a passage from one place to another: a drive around “The Peninsula,” for example, or a trip on the London Tube in “The Underground” and “District & Circle.” But there are frequently other journeys behind these journeys: “The Underground” invokes Orpheus’ hunt for Eurydice in the land of the dead, and in “Crossings,” Heaney and his fellow civil-rights marchers are

herded shades who had to cross

And did cross, in a panic, to the car

Parked as we’d left it, that gave when we got in

Like Charon’s boat under the faring poets.

In Irish literature, a visit to the other world was common enough to have its own genre, the echtrae. One of Heaney’s most well-known poems, based on an episode from the Irish annals, inverts this formula: in the sequence “Lightenings,” a trespasser from the other world visits ours. The monks of Clonmacnoise are at prayer inside the oratory when a ship appears above them and its anchor “dragged along behind so deep / It hooked itself into the altar rails”:

A crewman shinned and grappled down the rope

And struggled to release it. But in vain.

“This man can’t bear our life here and will drown,”

The abbot said, “unless we help him.” So

They did, the freed ship sailed, and the man climbed back

Out of the marvellous as he had known it.

Heaney’s poetry always establishes that “marvellous”: not simply by locating wonder in the ordinary but by throwing that big switch in the last line, when the viewpoint swivels around to the crewman. Moving from one place to another in Heaney is often a figure for crossing the ultimate threshold, that of the self, without which empathy would be impossible.

Heaney began work on Aeneid Book VI shortly after his father’s death, in 1986, and was still tinkering with it in the final months of his own life. His family had a long and careful debate before publishing it, but, according to Matthew Hollis, the poetry editor at Faber and Faber, finally decided that the “typescript that he left behind had . . . reached a level of completion that suggested it would not be inappropriate to share with a wider readership.”

They needn’t have worried: the work more than holds its own within Heaney’s oeuvre. (There’s also an aptness to its incomplete state. Virgil spent a decade on the Aeneid and was far from finished with it when he died in 19 b.c. He left orders that the poem be burned; his literary executors, as literary executors will do, ignored them.) Unlike Heaney’s celebrated translation of Beowulf (1999), for which he created what he called “Scullionspeak” to wrest the Anglo-Saxon into a living vernacular straight out of mid-Ulster, his Aeneid Book VI is not an appropriation. It’s more measured, the diction tending toward the classical, with the odd demotic touch. (Occasionally Heaney uses a syntax — verb-subject-object — that will be familiar to the Ulster ear: “Take you the sword from your scabbard.”)

The book as a whole is instilled with Heaney’s mastery of music — of rhythm, meter, and lineation. It opens with Aeneas, who has by now “foreseen and foresuffered all,” leading his fleet to “ride ashore on the waves at Euboean Cumae.” The rolling, fluid syntax abruptly gives way to a series of short, crisp phrases — “Anchors bite deep, craft are held fast, curved / Sterns cushion on sand, prows frill the beach” — that suggest how the ships come to a floating halt. Sonic effects reinforce the sense of concatenation, of the chains tautening as the rounded sterns settle on the sand. Hard stresses are set mimetically against each other — “bite deep,” “held fast” — and Heaney loads the two lines with rhyme and assonance (“deep”/“beach”; “craft”/“fast”/“sand”; “curved”/“sterns”). The lines, like the cables holding the anchors and the ships, are pulled tight.

As with Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, from which it borrows liberally, Virgil’s poem begins in the middle of the action. Aeneas, the Trojan warrior (he has a walk-on role in the Iliad), is with his fleet in the Mediterranean; Troy has fallen to the Greeks and its citizens are searching for a new homeland. Juno, Jupiter’s wife, is angry with Aeneas because his descendants are prophesied to destroy Carthage, her favorite city. She orders Aeolus, the ruler of the winds, to conjure up a storm, but Neptune, angry that Juno is straying into his realm, steers Aeneas’ ships to shelter on the coast of Libya, not far from Carthage. When Aeneas enters the city, he meets, and charms, Queen Dido. She lays on a feast for the Trojans, and encourages Aeneas to recount the sack of Troy and all that has happened to him since, including his encounter with Helenus, son of Priam, the late Trojan king, who enjoined him to go to Hesperia (modern-day Italy). There, Helenus predicted, Aeneas would found a city — Rome — that would one day rule all others.

Thanks to Juno’s skulduggery, Dido falls in love with Aeneas at the banquet. A few days later, while they are out hunting, a storm forces them to shelter in a cave where, we are left to infer from Virgil’s description of the tempest — in Sarah Ruden’s 2008 translation: “lightning flashed. . . . On the mountaintops nymphs howled” — that love is consummated. Dido takes this as a pledge of marriage, but her illusion is short-lived: Jupiter soon sends Mercury to remind Aeneas that he needs to get going to Italy. He duly leaves, and Dido, heartbroken, kills herself. In Sicily, where the armada makes landfall, Aeneas observes the anniversary of the death of his father, Anchises, with a series of funeral games. One night Anchises’ ghost appears to Aeneas and tells him to go to the underworld, where he will find his father in the luminous fields of Elysium and receive yet another vision of his future.

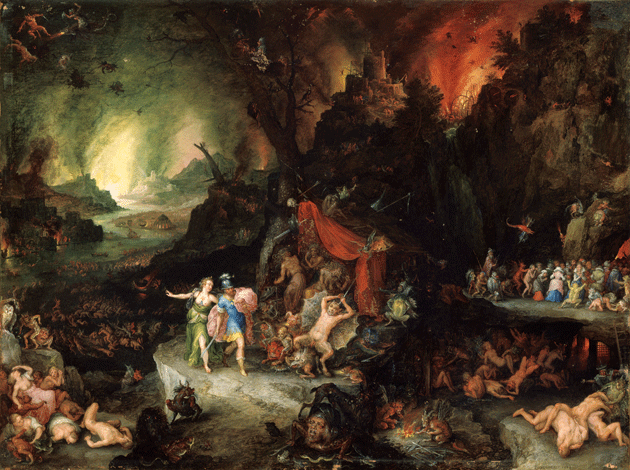

Which brings us to Book VI, the best-loved section of the epic. It’s here that we encounter the Sibyl of Cumae, the golden bough, Charon, Cerberus, the ghost of Dido, the rivers Styx and Lethe, the suicides, the massed souls waiting to be reborn, the gates of ivory and the gates of horn. The influence of Book VI on European literary culture has been profound and diffuse, from Dante’s Inferno to lyrics by such poets as Keats (“Ode on Melancholy”) and Louis MacNeice (“Charon”), but it also provides a number of what might be called deep metaphors — crossings, descents, underworlds — that underpin not just Heaney’s poetry but a great deal of Western literature.

How to review a translation? Compare, contrast; condone, condemn. Virgil wrote in dactylic hexameter — i.e., each line has six metrical feet and as many as seventeen syllables. Even though Latin, like English, is a stress-accented language, its prosody is based not on stress but on syllable length, and since Latin is an inflected language it allows a great deal of compression.

Can you pick Heaney’s translation out of a lineup? Here are three versions of the passage in which Aeneas, guided by the Sybil, confronts Cerberus, the big three-headed mutt — Heaney’s, together with those of Robert Fagles (2006) and Ruden:

1.

These

are the realms that monstrous Cerberus rocks with howls

braying out of his three throats, his enormous bulk

squatting low in the cave that faced them there.

The Sibyl, seeing the serpents writhe around his neck,

tossed him a sop, slumbrous with honey and drugged seed,

and he, frothing with hunger, three jaws spread wide,

snapped it up where the Sibyl tossed it — gone.

His tremendous back relaxed, he sags to earth

and sprawls over all his cave, his giant hulk limp.

The watchdog buried now in sleep, Aeneas seizes

the way in, quickly clear of the river’s edge,

the point of no return.

2.

Enormous Cerberus sprawled there in his cave.

The baying of his three throats filled that country.

The snakes rose on his neck, but then the seer

Threw him a cake of drug-soaked grain and honey.

With his three gaping mouths, in savage hunger,

He seized it, and his monstrous arch of spine

Melted, to stretch his huge form through the grotto.

Aeneas passed the guard, now sunk in sleep,

And hurried from the hopeless river’s banks.

3.

Here Cerberus keeps watch,

Growling from three gullets, his brute bulk couched

In the cave, facing down all comers. But the Sibyl,

Seeing snake-hackles bristle on his necks,

Flings him a dumpling of soporific honey

And heavily drugged grain. The ravenous triple maw

Yawns open, snaffles the sop it has been thrown

Until next thing the enormous flanks go slack

And the inert form slumps to the cave floor.

Thus, with the watchdog sunk in a deep sleep,

Aeneas gains entry and is quick to put behind him

The bank of that river none comes back across.

I realize it’s unfair to pit a poet’s translation of one book against a scholar’s version of the whole, but that is indeed what I’m going to do. Fagles (1), for all his diligence and poetic invention, never says something once when he can say it twice. We don’t need, for example, that “where the Sibyl tossed it”: he’s already told us that the Sibyl threw the dog a sop and that he gobbled it down. Virgil may use “obiectam” in the original (“the cake thrown [him]”) but an English rendering doesn’t need to unpack the grammatical inflections unless they’re required for sense. Similarly, if Cerberus’ back is “relaxed” and he “sprawls all over the cave,” do we need to be told that his “giant hulk” is “limp”? The diction is also uneven: “slumbrous” is both archaic and overliterary, and the phrase “the point of no return” is simply a cliché.

Ruden (2), who opts for line-by-line metrical equivalence, stands up better; her version has the considerable benefit of concision and a nice dry clean diction. There is a modesty to her poetic devices — the iambic backbone, the occasional alliteration — that make her highly readable but also, at times, a little flavorless. Fagles, by contrast, can be overcooked.

Heaney’s translation (3), which also uses a roughly iambic line, contains one or two redundancies (“the sop it has been thrown”) but is, on the whole, a clear improvement on Fagles and Ruden. The surety of the pacing and the heavy alliteration in those opening phrases heighten the tension of the encounter. Two main assonantal ripples run through the passage (“growling”/“seeing”/“flings him”/“dumpling”; “maw”/“yawns”/“sop”/“across”/“form”/“floor”), which is also marked by a submerged verbal playfulness: that the dog is “facing down all comers” slyly puns on his having three faces. The rhythmic control is admirable, too, as when those three hard stresses fall together in “the inert form slumps to the cave floor.” We can almost hear the three drugged heads dropping at the travelers’ feet.

Or consider Virgil’s description of the suicides, whom he refers to as “maesti” (“the sad ones”). Fagles:

The region next to them is held by those sad ghosts,

innocents all, who brought on death by their own hands;

despising the light, they threw their lives away.

How they would yearn, now, in the world above

to endure grim want and long hard labor!

Ruden:

Beyond this, dismal suicides are lodged.

Though innocent, they threw away their breath

In hatred of the light. But now they’d cherish

Hardships and poverty, beneath the sky!

Heaney:

Farther on

Is the dwelling place of those unhappy spirits

Who died by their own hand, simply driven

By life to a fierce rejection of the light.

How they long now for the open air above,

How willingly they would endure the lot

Of exhausted workers and the hard-wrought poor.

Nothing compares well with Heaney’s “simply driven / by life to a fierce rejection of the light.” There’s that propulsive assonance (“simply driven”) and those clear stressed monosyllables, “life” and “light,” topping and tailing the line. Virgil’s Latin states that the suicides “lucemque perosi proiecere animas”: “the light detesting have cast away their lives.” “A fierce rejection of the light” is a fine rendering of the line, warranted by the strength and energy of “perosi” and “proiecere.” At the same time, the choice of “fierce,” which hints at the resolution needed to commit such an act, shows Heaney’s characteristic empathy. Whatever else it may be, he gently insists, to kill oneself requires courage. Throughout Heaney’s work you find this kind of simultaneous study in ethics and aesthetics, and the suggestion that they are in the end the same.

The Aeneid has long been read as a poem in tension with itself. Virgil envisaged an epic that would constitute a founding myth for the Roman Empire and a justification for military campaigns past and present, and yet much of its second half, which depicts the various battles that Aeneas and his men undertake in their quest for a new home, cannot help but register the futility and pity of war. Book IX, in particular (Heaney’s A-level set text), is a relentless catalogue of slaughter. The tone is ambiguous. For example, after the Trojans Nisus and Euryalus have crept into the Latin camp and killed many of their sleeping enemies, Virgil writes (in John Dryden’s 1697 translation):

Nisus observ’d the discipline, and said:

“Our eager thirst of blood may both betray;

And see the scatter’d streaks of dawning day,

Foe to nocturnal thefts. No more, my friend;

Here let our glutted execution end.

A lane thro’ slaughter’d bodies we have made.”

“Discipline” implies admiration for the carnage Nisus has wrought, but other diction works against this reading: he sees himself as bloodthirsty, a purveyor of “nocturnal thefts,” and a glutted executioner. Virgil also humanizes and individualizes Nisus’ victims:

Lamus the bold, and Lamyrus the strong,

He slew, and then Serranus fair and young.

From dice and wine the youth retir’d to rest,

And puff’d the fumy god from out his breast:

Ev’n then he dreamt of drink and lucky play —

More lucky, had it lasted till the day.

It’s hard not to feel for the luckless Serranus. If the work is a celebration of Rome’s imperial dynasty, it’s also a condemnation of it.

“Pious Aeneas,” as he’s described, embodies these contradictions; his destiny, to found Rome by means of violent conquest, seems to go against his essentially decent and charitable nature. In this, we can see yet another way in which Virgil’s poem shaped Heaney’s imagination, for which the conflict between compassion and tribal loyalty, between human understanding and historical exigency, was of perpetual concern. In “Punishment,” from North (1975), the poet empathizes with both the victim of an ancient rite of communal retribution (“I can feel the tug / of the halter at the nape / of her neck, the wind / on her naked front”) and its perpetrators. For all the horror of the imagined spectacle, Heaney knows that he, too, would have cast “the stones of silence,” and admits that he understands “the exact / and tribal, intimate revenge.”

In the Aeneid, the costs of military expansion are not only moral; they are also poetic. Heaney writes in his preface of the “grim determination” needed by the translator to get through the climax of Book VI, where, in several tedious passages, Anchises enumerates the future heroes of Rome. Heaney anticipates our boredom, noting that “the roll call of generals and imperial heroes, the allusions to variously famous or obscure historical victories and defeats, make this part of the poem something of a test for reader and translator alike.” Still, its longueurs notwithstanding, Aeneid Book VI is a remarkable and fitting epilogue to one of the great poetic careers of recent times. We should be glad that Heaney summoned the perseverance to finally finish his homework.