A motley crew steers Anne Carson’s FLOAT (Knopf, $30). There’s Edmund Husserl, Jean-Luc Godard, Joan of Arc, Pablo Picasso, mad Hölderlin, Hegel, a chorus of Gertrude Steins, and Carson’s noble, demented uncle Harry, not to mention the usual Greek suspects: late-arriving Odysseus, howling Cassandra, and a rather tetchy Zeus. What else would you expect from Carson — renowned classicist, translator, and polymath? The book is actually a collection of twenty-three chapbooks of poetry, drama, and mental peregrinations stacked in an acetate case; most have been published or performed before, but a few are new or expanded. Whether one skims or dives, there are treasures to be found. The two playlets of “Uncle Falling” plumb family tragedy; “Powerless Structures Fig. II (Sanne),” about the death of Carson’s brother’s wife, is a heartbreaker; “Eras of Yves Klein” and “Good Dog I, II and III” are goofy fun; and from the essay “Contempts,” I learned a new way of looking at Brigitte Bardot’s bottom. Still, the question arises: twenty-three chapbooks?

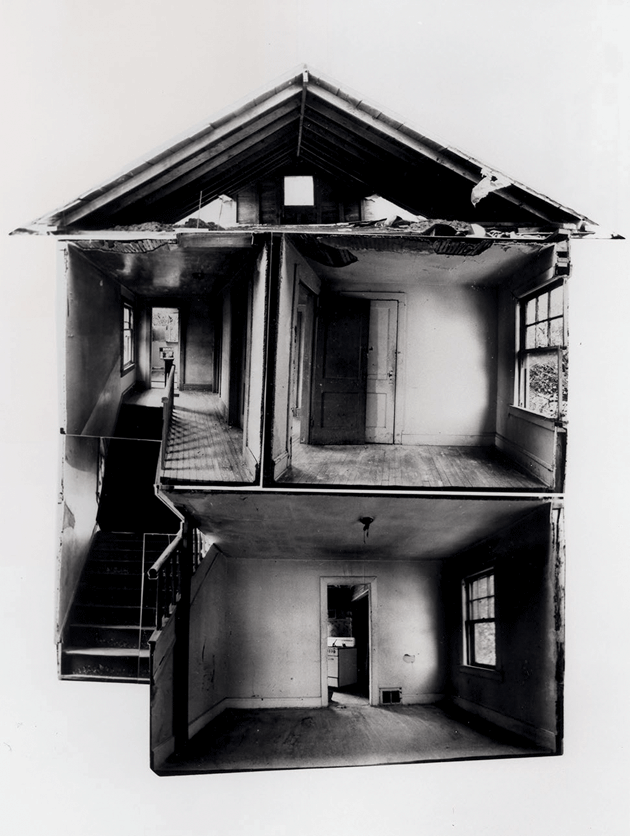

“Splitting,” 1974, by Gordon Matta-Clark. Courtesy the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark; David Zwirner, New York City/London; and Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

Perhaps Carson and her publishers simply felt it was time for another book, and this was the material they had on hand. It’s doubtful anyone would cry foul if one of the sheaves went missing and another appeared in its place, but the whole coheres. The tether is Carson herself — her interests, erudition, and autobiography; the way she thinks, and writes, and, occasionally, rhymes. As Gordon Matta-Clark, another artist who surfaces in Float, once put it, “You are the measure.” That was a play on Protagoras, the pre-Socratic philosopher who declared that “man is the measure of all things.” Indeed, replacing universal, abstract “man” with a particular individual is as essential to Carson’s project as the Greek language itself — a language that, had it not been for the ministrations of a “bored high-school Latin teacher” and a free lunch hour, she might have missed learning altogether. “My entire career as a Classicist is a sort of preposterous etymology of the word lunch.”

“Preposterous etymology” is not a bad term for the kind of argumentation she favors. The critic Dan Chiasson has noted that although Carson has a reputation for difficulty, she is in fact didactic, a simplifier and hand-holder who spells it all out. Float sinks when it becomes overly insistent on associations that rub out meaningful distinctions. “I started to think about bodies falling,” she writes, citing Achilles’ horses dropping their manes to the ground, her father parachuting into combat in World War II, humans going into their graves, and a baby “falling . . . from between the knees of its mother.” (I thought they were pushed out.) Nor can I catch her awe for the untranslatable. Her question “What else is one’s own language but a gigantic cacophonous cliché?” rings with disdain for the beauties and games of ordinary language.

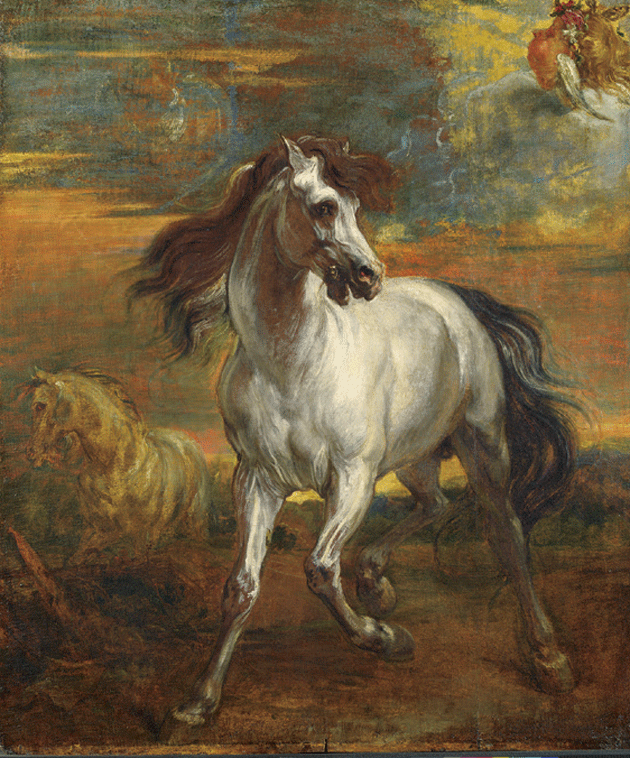

The Horses of Achilles, c. 1650–1725, in the style of Anthony van Dyck © National Gallery, London/Art Resource, New York City

“If words are veils,” she writes, “what do they hide?” For Carson, words most definitely are veils, and the mystery they cover is “our whole way of knowing the truth.” “Cassandra Float Can” veers from the scene in Agamemnon in which the Trojan prophetess erupts in perfect Greek to Matta-Clark’s “splittings” — houses that he literally sawed in half. She is enamored of fissure, disruption, “the action of cutting through surfaces to a site that has no business being underneath.” It is true that when Matta-Clark split a house open, he transformed space. But what he found underneath the surface had, strictly speaking, all the business in the world being there: it was more house. A little mundanity can be a tonic, and sometimes the view is clearer if one steps aside and peers over Carson’s shoulder, rather than through her periscope.

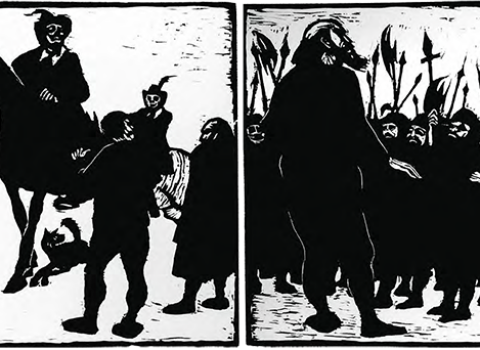

An author who would do best to get out of the reader’s way completely is Sarah Glidden. Her graphic memoir ROLLING BLACKOUTS: DISPATCHES FROM TURKEY, SYRIA, AND IRAQ (Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95) documents a trip she took in 2010 with editors from the Seattle Globalist, an online news outlet, to report on Iraqis who had been displaced by the American invasion and its aftershocks. Recent portraits of Syrian Kurds by Molly Crabapple and Olivier Kugler are humane and urgent, crowded with the words of the refugees themselves. Glidden’s clean, spare cartoons take a behind-the-scenes approach. Readers expecting a book about the region and its recent history may be surprised at how many pages are taken up with heartfelt conversations on the theme, “What is journalism?” Most curious is the role played by one of the editors’ friends, Dan, a former Marine (he ran convoys out of Ramadi), who has also tagged along on the trip; while Dan makes a video blog, the Globalist editor fails to provoke him into admitting that ousting Saddam Hussein was a mistake. Dan contains multitudes — he protested against the war, then enlisted — but what’s really notable is how his journalist friend can’t hear what he’s trying to say.

A panel from Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches from Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, by Sarah Glidden. Courtesy Drawn & Quarterly, Montreal

The book comes alive when the Americans recede from the frame. Glidden draws excellent grimaces, arched eyebrows, and narrowed eyes; her smiles are good, too, but she has less cause to use them. We meet Momo and Odessa, art students who had to leave Baghdad when their friendship with American soldiers put them at risk; Hiba, who volunteers at a women’s center; and assorted middle-aged professionals who have fallen into poverty. The Americans spend several days with Sam Malkandi, a footnote to The 9/11 Commission Report. Malkandi fled to Iran during the Iran–Iraq War, later registered as a refugee in Pakistan, and — after lying on his asylum application, a common practice — was resettled in the United States in 1998. He allowed a man he met at a mall in Seattle to use his address on a medical form; the man was later identified as a bin Laden operative. Malkandi, who denies any foreknowledge of the 9/11 attacks, was deported in 2010 on immigration charges. The Globalists are on the case. “It can’t just be random. It can’t just be terrible luck,” the editor cries, eyes bugging, cigarette cocked. “There’s got to be some sort of explanation!”

It was not so long ago that Syria was a refuge. “You see people on the street here and everyone seems happy,” Dan unwittingly prognosticates, “but I’m sure you could find something that would make them all pick up guns and kill each other.”

The global village comes in for European treatment in David Szalay’s ALL THAT MAN IS (Graywolf, $26), a story collection that could have been titled Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, if that weren’t already taken. Each of Szalay’s nine narratives involves a male protagonist adrift — sometimes on a yacht or treading water in a pool; other times simply out of place, bouncing from city to city, staying in uncharming hotel rooms, drinking in cheap bars or at seedy seaside resorts. The stories begin in medias res, often with an unidentified “he” who slowly comes into focus, and break off without resolution. Short sentences and one-line paragraphs create an effect that is collaged, not choppy.

Female minor characters are on hand to catalyze male existential crisis. There’s a dead mother, a horny Czech landlady who beds a British teenager while her husband is away, a Hungarian sex worker, a Polish TV newscaster who refuses to get the abortion her medievalist boyfriend is gunning for, and an obese mother–daughter pair of English tourists who screw the same French loafer on consecutive days in Cyprus.

The book is a wreck of intimacy issues, second choices, and cheap Ryanair flights. “This is my life” is the shared, stunned epiphany of the men. Even those who have made it in worldly terms are unable to feel satisfaction. “I’m very proud of what I’ve achieved,” thinks an elderly Englishman holed up in his villa outside Ravenna (Tuscany was too expensive):

Which is true. Even as he says it, though, he is aware of how weightless, how intangible, how even strangely fictitious, his achievements feel — even the ones he is proudest of, like his minor part in negotiating, over many years, the expansion of the European Union in 2004. Something, he is not sure what, seems to nullify them.

The Brexit moment gives this passage extra pathos, but it hardly needs history to have an impact. What captivates Szalay is a hopeless attitude unmoored from any circumstance. The most memorable characters are the biggest losers, such as the unemployable Murray, who has moved from the U.K. to a shabby Croatian village to stretch his savings and subsist on kebabs and local lager. His interior life is not so different from that of the Russian oligarch who made his fortune in iron ore and lost it in miscalculations.

He had nothing left to live for. He had devoted his whole life to something, and it had failed.

What else did he have left to live for?

Nothing.

It was over. That was it.

Cruel, vacant masculinity has its place in SUITE FOR BARBARA LODEN (Dorothy, $16), a little gem by Nathalie Léger, translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon. Assigned to write the entry about Wanda (1970), Barbara Loden’s art-house movie, for a film encyclopedia, Léger let herself get lost. The result gracefully melds criticism, fiction, and autobiography, and is a powerful example of how summary, channeled through the most personal of perspectives, can be a form of art:

They drive around in silence, he is clutching the steering wheel, tense and irritable, like a husband and father who’s been ruined and is considering the idea of collective immolation at the next service station; she sits the way my mother used to sit next to my father, upright, short, alert, holding her breath, just waiting to be murdered.

In the character of Wanda — a lethargic housewife from Pennsylvania coal country who gives her ex-husband custody of the kids and, by a sheer accident of timing, is taken up by a desperate lowlife she calls Mr. Dennis — Léger sees a refraction of Loden, the film’s writer, director, and listless, fragile star. Loden had been a lonely teen model who danced at the Copacabana, and became the second wife of Elia Kazan; Wanda was the first and only film she directed before dying of cancer at forty-eight. “As she lay dying all she said was, Shit, Shit, Shit, then she spat out some tiny stones — it’s the liver, the nurse said — and died.”

Although feminists hated the passivity of Wanda — imagine the agony of Jeanne Dielman but without the knife — Loden wasn’t trying to make a statement. The film is pure atmosphere. It provides no answer to the mystery of what went wrong in Wanda’s life, why she became a drifter. Something has wounded her, but maybe it was just the times. “The typical 1970s woman,” Léger writes memorably,

is a woman who’s wondering what she’s actually going to be able to do with the freedom that everyone keeps telling her about; a woman who wonders what new lie she’ll have to make up now, how she’s going to pretend to be cool, so that all these men will finally leave her the hell alone.

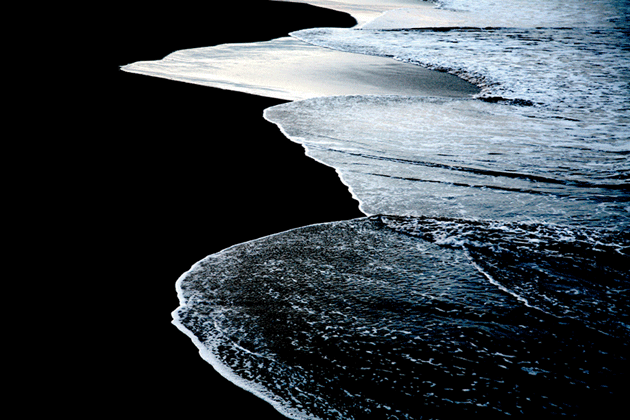

Wanda loses everything, but she can’t get free. The last scene shows her in a bar, blankly pressed up against loud merrymakers. Léger paraphrases Louis-Ferdinand Céline: “When you’ve reached the very end of all things, and sorrow itself no longer offers an answer, then you must return to the company of others, no matter who they are.” Everyone washes up on some shore.