Until the U.S. government got wind of it, the sharpest critic of the Mormon practice of polygamy was Joseph Smith’s legal wife, Emma. But as Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explains in A HOUSE FULL OF FEMALES: PLURAL MARRIAGE AND WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN EARLY MORMONISM, 1835–1870 (Knopf, $35), a lot of Latter-day Saints didn’t cotton to the idea at first — not even Joseph.

John Taylor said it made his flesh crawl. Lucy Walker compared it to “a thunderbolt” and said every feeling of her soul “revolted against it.” Brigham Young claimed it was the first time in his life he had ever desired the grave. Lorenzo Snow testified that Joseph, too, resisted the revelation until an angel “appeared before him with a drawn sword threatening him with destruction unless he went forward and obeyed the commandment.”

Obey he did. In my Father’s house are many mansions, and the prophet needed them all. At the time of his death, in 1844, he was married, or “sealed,” to more than two dozen women, who may or may not have known about one another; fourteen years later they still flocked to the temple to unite with him by proxy. Most polygamous families, however, could make do without building an addition. By 1860, 40 percent of Utah’s men, women, and children lived in a household with more than one wife, but two thirds of these were shared by only two wives, and another fifth had three. (The men with larger harems tended to be church leaders.) The terms of these marriages varied. Some were entered into for earthly life; some were “celestial,” or for eternity. It was possible to have children with one man that would be with another man’s family in paradise.

Photograph of four prominent Mormon women, July 16, 1867, by Edward Martin © Intellectual Reserve. Courtesy Church History Library, Salt Lake City, and Alfred A. Knopf

O pioneers! Ulrich stitches together diaries, poems, meeting minutes, and quilt designs into a fascinating history of women’s lives. Tough doesn’t begin to describe it — they drove wagons across the frozen Midwest, bore and buried children, spoke in tongues, farmed, and organized relief societies while the men traveled on missions. (They drank and danced too.) Even the women who disliked polygamy defended it — or, like Emma, used it for leverage. When she threatened divorce, Joseph gave her the deeds to a steamboat and sixty city lots in Nauvoo, Illinois.

Ulrich suggests that Emma may have wanted something to fall back on, a reasonable desire given how persecuted the Mormons already were. Plural marriage increased the ire. Newspapers compared Mormons to Turks, Africans, and Indians; the Republican Party platform of 1856 likened polygamy to slavery. In 1870, faced with the Cullom Bill, which threatened to claim Mormon property and jail Mormon men, the wives rose up. Twenty-five thousand women attended fifty-eight meetings across the territory, and their fury bled into calls for suffrage; Utah granted women the right to vote that year, half a century before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Integration into the political system did not result in the preservation of religious tradition. Caught between the federal whip and the sword of the angel, the Mormon Church repealed the doctrine of plurality in 1890.

This is her first scholarly book on the Latter-day Saints, but Ulrich, herself a Mormon, has been thinking about what she calls “early Mormon feminism” for a long time. Fifteen years ago, she published an article in the Journal of American History in which she lionized nineteenth-century Mormon women as a “model for religious commitment, social activism, and personal achievement.” Anyone else in need of reassurance that family, faith, and intellect can live together need only consult her biography. In addition to rearing five children, Ulrich has taught at Harvard, run the American Historical Association, written several field-defining books, won a MacArthur and a Pulitzer Prize, and coined the phrase “well-behaved women seldom make history.” “I was raised to be an industrious housewife and a self-sacrificing and charitable neighbor,” she wrote in that journal article, “but sometime in my thirties I discovered that writing about women’s work was a lot more fun than doing it.”

Women who entered into plural marriages were often vulnerable: young, fatherless, poor, or foreign. Still, one does well to recall Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s remark after a visit to Salt Lake City: so long as women were not working for their own money, being a monogamous helpmeet was hardly less oppressive than being one of several spouses. It wasn’t difficult to break up a marriage in the nineteenth century — unless there was property at stake, one party usually just left town — but plural marriages were even easier to dissolve. That’s because Mormonism imagined marriage in modern terms, as an institution to foster mutual happiness, and allowed a woman to abandon one arrangement for another at whim. It reminds me of the old custom of wife-selling in England, which women used to escape abusive or unsatisfying relationships or leave a husband for a lover.

Although Smith does not seem to have enjoyed biblical knowledge of many or even any of his wives other than Emma, Utah’s population explosion of the 1860s indicates that subsequent practitioners dedicated themselves to procreation. For the women, this meant distributing childbearing and child-rearing labor into “reproductive collectives.” For the men, it was pure sex work. The Saints “simultaneously glorified reproduction and urged sexual restraint. . . . A man who married multiple wives in order to indulge his lascivious impulses was as guilty of adultery as a monogamist who strayed from his marital vows.”

Lascivious impulses are everywhere in Ottessa Moshfegh’s fiction, but nothing as vanilla as God-glorifying polygamy. Her deviants are turned on by strangulation, shoving fingers in mouths and up assholes, taking laxatives, smelling their own genitals, and the intoxicating abandonment of decency. “I wanted to be ruined,” says one narrator in the story collection HOMESICK FOR ANOTHER WORLD (Penguin Press, $26). “I let her do whatever she wanted to do to me that day in the cabin,” says another. “It wasn’t painful, nor was it terrifying, but it was disgusting — just as I’d always hoped it to be.”

The person speaking in that story has a wife. Who knows why he can’t enjoy his disgusting fantasies with her? Maybe he doesn’t care enough about her to show her his underbelly. (Nietzsche: “One beats the dogs one likes best.”) In Moshfegh’s world, strangers, not intimates, permit behavior that is both savage and unaccountable. A different narrator speaks of the “odd coincidence of lonesomeness and availability” that drove her into a relationship with a man she met at the Good-Time bar. Once he introduces her to the “zombies” at the bus depot, the two forget the sex and become drug buddies; the powder “blotted out all our feelings for each other.” The malcontents of Homesick like to get high, but what really gets them off is contempt, for themselves and for others. They never stop insisting on their perversity, though one would have to have a fairly limited view of normalcy to find them shocking.

Sentences looped and pulled into perfect slipknots: Moshfegh’s ear is original, and her command of form, expert. I would read anything she writes. But while the individual stories sting, in the aggregate they buckle a little under the senselessness of her vision. Some of her characters are drunks; others stumble about committing cruelties for no clear reason. This tendency to the arbitrary is most obvious in her novel Eileen, a clunky thriller whose plot hangs on an undermotivated crime. (That Eileen was celebrated as “Hitchcockian” only shows how little people understand Hitchcock, whose crimes are always psychologically overdetermined.) Moshfegh’s best characters are those who are frantically burrowing toward some crumb of self-knowledge, in one case literally: the narrator of the novella McGlue nearly kills himself trying to dig his fingers into his own brain.

“A Better Place,” the last story in Homesick for Another World, reads like a fairy tale. The narrator is a little girl consumed with thoughts of returning — somewhere. We don’t know anything about where she thinks she’s from, except that it is far away, and can be arrived at only by either murdering the right person or committing suicide. “Why is it, Waldemar,” she asks her brother, “that when something here is so beautiful, I just want to die?” He answers, “Because it reminds you of the other place. . . . The most beautiful place of all.” The girl recalls

an old lady who lives between the cans of garbage behind the market. . . . She seems to be making the most of her time on Earth, though, doing as she pleases. She doesn’t work or have a crying baby to tend to. Nobody is going to get near her. Nobody is going to make her black and blue and bloody. She smells like so many toilets. But she does as she pleases. She is a grown woman.

The gutter, Oscar Wilde knew, is a good place to look at the stars. What Moshfegh’s characters are dreaming of, as they lie there smelling like toilets, is freedom — a negative freedom, a horrible freedom, but the only one their view affords.

Stargazing in your own filth sounds like the perfect occasion for a smoke. Gregor Hens’s NICOTINE (Other Press, $16.95), translated from the German by Jen Calleja, is a satisfying wisp of an essay about tobacco, addiction, first cigarettes, last cigarettes, breathing, kissing, hypnosis, literature, memory, and marking time. He came by his love of the drug honestly. When he was a mere tot, strapped in the back seat on a road trip, his parents chain-smoked with the windows rolled up. “I’d push open the door, shuffle out breathing stertorously with an overly acidic stomach, and stagger sleepy and thirsty and strangely excited towards the rented chalet.” His mother gave him his first cigarette, a Kim, one thrilling New Year’s Eve when he was five or six years old. He used the tip to light a bottle rocket, then helped himself to a drag. “Life was no longer composed of individual moments. . . . In this manner, I was offered for the very first time an experience that was narratable.” Hens felt “an inner world” open up. He’s given up inhaling, but he still thinks and works in half-hour chunks.

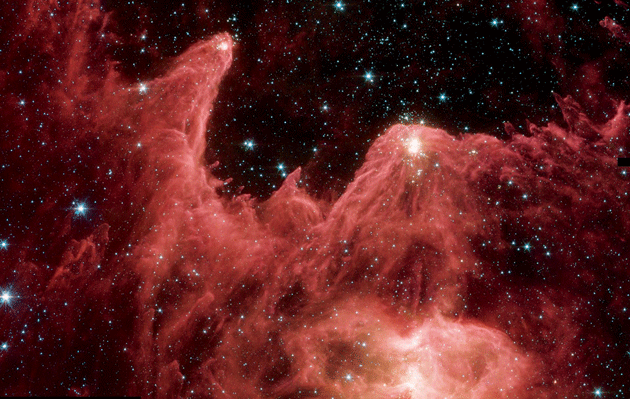

A false-color image of the Cassiopeia constellation, taken by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. The mountainous pillars are where stars are born. Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/Harvard-Smithsonian/ CfA/ESA/STScl.

Nicotine is a smoke ring, blown perfectly in a single puff, or — better? — a wafting trail of vapor. Will Self contributes a foreword, a rapid monologue punctuated with vigorous little twists, as though he were grinding out a stub with yellow-stained fingers. “It’s the way a smoking habit is constituted by innumerable . . . incidents — or ‘scenes’ — strung together along a lifeline,” Self writes, “that makes the whole schmozzle so irresistible to the novelist.” Italo Svevo’s Zeno Cosini loved the ritual of the last cigarette (L.C.), and enjoyed it a hundred times. Hens prefers the relapse cigarette: “I’ve always smoked the last cigarette because I could already sense that a new first one was awaiting me at some point in the future.” He quotes a scene from the movie Blue in the Face, in which Bob (Jim Jarmusch) visits his tobacconist friend Auggie (Harvey Keitel) to smoke his L.C. Bob “voices the natural fear that not smoking after sex could be especially difficult. Auggie doesn’t understand: You’re giving up sex too because you can’t smoke afterwards?” There’s one problem the Mormons don’t have to deal with.