“We’ve had a bit of a crisis,” Hughes de Courson told me on a raw Parisian morning last February. I’d found him slumped at a table overlooking the cobblestones of the Place Émile-Goudeau, trying to mollify his much younger girlfriend, Naomie Assana. Courson explained that they had spent the previous night drinking a fair amount of wine in Versailles, and this morning their hostess had asked them to leave, claiming they’d kept her up all night. Exhausted, they had returned to the city and checked into this modest hotel in Montmartre.

Courson, a sixty-nine-year-old with shoulder-length gray hair and an earring, exhibited the louche nonchalance one might expect of a decrepit rocker. A founding member of Malicorne, an electric folk band of the Seventies, he has enjoyed a long musical career that included performing Mozart in Morocco and rewriting the national anthem of Qatar. (“I gave them two versions,” he said, “one very Arabic, one very ‘God Save the Queen,’ and you can guess which one they chose.”) Our meeting, however, had less to do with his résumé than with his connection to literary history through his old songwriting partner, Patrick Modiano.

Modiano, who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014, is considered one of the foremost chroniclers of Paris during the Second World War, but he was barely known outside France before his victory in Stockholm. Even in his home country, Modiano remains an ill-defined figure, an awkward introvert who spends his days thumbing through telephone books from the Forties. Since the flurry of attention that followed his Nobel win, Modiano has rarely spoken to the press, and the interviews he does grant are hardly informative. On camera Modiano appears hesitant and shy; he stammers, waves his long arms, and trails off midsentence. So I was intrigued when I learned that as a young man, Modiano wrote song lyrics, some of which were recorded by Francoise Hardy and other stars of the Sixties. I was surprised by the pop ambitions of a future laureate, and it occurred to me that Modiano’s musical collaborators might prove a more fruitful way to access this elusive writer than traditional lines of inquiry.

An internet search revealed that in 1979 Modiano released a record entitled Fonds de tiroir 1967. Fonds de tiroir means “the bottom of the drawer,” and Modiano’s liner notes explain the offhand title he chose for songs he’d written more than a decade earlier:

Everything ends up in drawers. You just have to open them to find again the lost years, with the dried flowers, the yellowed photographs, and the songs. Someone has said that the best way to relive the passed moments are scents and songs. What are the scents of 1967? I don’t know, but in the meantime I found in the bottom of a drawer a few songs that Hughes de Courson and I wrote in this particular year.

At the hotel in Montmartre, Assana retreated upstairs to nurse a headache, but Courson persevered in the lobby with me. Too distracted for a sit-down interview, he offered a walking tour of his old neighborhood instead. We took the metro south to the Latin Quarter and strolled down the Left Bank, where the booksellers on the Quai des Grands Augustins reminded Courson of a memory from his school days.

“Patrick would always offer the sellers three books,” he said, “and he’d place the book with a forged signature of the author in the middle, as if he didn’t know that he had something precious.” Without a word about the valuable autograph, the bookseller would hastily close the deal, believing he was taking advantage of a distracted young man. But it was the opposite. “With Patrick,” said Courson, “everything is camouflage.”

Patrick Modiano was born in a suburb of Paris in July 1945, to Louisa Colpeyn, a Belgian actress, and Alberto Modiano, a Jewish businessman of Italian heritage. After Modiano’s only sibling, a brother named Rudy, died at the age of nine, he was shipped off to live with strangers and attend mediocre prep schools, from which he tended to run away.

Modiano published his first novel in 1968, when he was twenty-three, and a decade later won the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious literary prize. Until the announcement in Stockholm, however, the Paris literary elite treated Modiano with condescension. Many believed that his novels, structured like detective stories and easily consumed in an afternoon, went down too easily and sold too well.

Modiano has now released nearly thirty titles, but to many readers — and indeed to the writer himself — it seems that each new book is another take on the same story. Again and again, he returns to Paris during the Second World War and its aftermath, as his characters try to find out how an old friend or lover survived the German occupation.

At the start of the war, France was home to 330,000 Jews, more than half of whom had recently emigrated from elsewhere in Europe. In 1941, after the French capitulation, German authorities ordered all Jews over the age of six to wear a yellow star, and a year later the first convoy departed for Auschwitz. With the active collaboration of the Vichy government, more than 75,000 Jews were delivered to the death camps.

Modiano, whose father refused to wear the yellow star and survived by trading with the Germans on the black market, was one of the first postwar writers to question the story of widespread French resistance that had held sway when he was a child. In 1974, he co-wrote the screenplay of Lacombe, Lucien, Louis Malle’s film about a simpleminded farmhand who joins the Gestapo — which was a landmark in the French public’s reassessment of the war’s legacy.

Over the following four decades, Modiano has probed the country’s conscience in novels that squint into the dark corners of the occupation. How did he vanish? Who raped and murdered her? Or, in the case of Guy Roland, the amnesiac detective from Missing Person, Who am I? Modiano is as adept as any crime novelist at planting questions in the reader’s mind, but they are never answered with satisfaction. His obsession with memory — with its seductive slipperiness and, most of all, with its failings — has led many to compare him to Proust, but Modiano conjures the past in a cinematic style that is short on detail and long on atmosphere. “It would soon be the time of night,” he wrote in So You Don’t Get Lost in the Neighborhood, “when the makeup starts to run and you are on the brink of revealing secrets.” Like pulp, his novels evoke a noirish demimonde of hustlers, gamblers, and libertines, where identities are uncertain and allegiances are in flux.

In Honeymoon (1990), as in so many Modiano novels, one mystery leads into another. Over a drink at a hotel bar in Milan, Jean B., a documentary-film maker, learns by chance of the suicide of a middle-aged woman named Ingrid, who had been kind to him as a young man. Rather than return to his project in the Brazilian jungle, he hides out in a cheap hotel on the outskirts of Paris, ignoring his career and floundering marriage to dwell instead on Ingrid’s past. Jean B. imagines that during the war, the sixteen-year-old Ingrid evaded the authorities in Paris and fled with her boyfriend to the south of France, where they posed as newlyweds. (We assume that Ingrid is Jewish, though her religion is not made explicit.) Modiano never reveals why Ingrid killed herself so long after enduring the worst of the occupation, beyond a sense that past traumas had caught up with her, as they had with Jean B., and perhaps with the whole of France.

Honeymoon contains many of Modiano’s persistent themes, which he has described as an obsession with “disappearance, the problems of identity, amnesia, and the return to an enigmatic past.” Born two months after the war’s end, Modiano writes for the generation once removed, whose lives were tainted by events they did not experience yet could not escape. “You were right to tell me,” Guy Roland says in Missing Person, “that in life it is not the future which counts, but the past.”

Modiano and Courson met as classmates at the prestigious Lycée Henri-IV in 1965, when they were twenty and nineteen, respectively. Modiano was six and a half feet tall, pale, emaciated, and high-strung, while Courson was about a foot shorter, a long-haired rebellious imp with a guitar. Courson told me that, like most of his generation, he was addled by sex, rock and roll, and revolution. Modiano, however, showed little interest in any part of that trinity. Instead of the Beatles and the Stones, he listened to prewar singers — Luis Mariano, Irène de Trébert, Reda Caire — and, although his fellow students would soon be storming the barricades, he never attended a demonstration. According to Courson, Modiano was cynical about youthful attempts to reshape the world, and focused instead on securing his own comfortable future.

Modiano’s appetite for luxury may stem from the privations of his childhood. In Pedigree, a bitter memoir that is as elliptical as his novels, Modiano doesn’t see fit to name either of his parents and refers to his ancestry as “dung.” He writes that he felt most like himself when he was out searching for “curiosities.” He and Courson often walked the streets of Paris all night; they hung out in cafés and played pranks, harmless and otherwise.

Courson insisted that Modiano was nothing like the awkward fellow glimpsed in interviews. He told me that Modiano had a wonderful, dark sense of humor, and would often hatch subversive schemes, such as proposing to the director of the boy scouts that they write an explicit new manual called Le patrol rose, which would take the group’s homoerotic undertones two or three steps further.

Starting in their early twenties, however, their favorite pastime was whipping off songs. Modiano could produce complete lyrics as fast as he could jot them down, and Courson composed the melodies almost as quickly. They rarely spent half an hour before arriving at a finished product. How, I asked, did he and Modiano work? Did they discuss ideas, or did Modiano present him with a text? It could be either, Courson said, but it was mostly a matter of turning a poem into a song. “Patrick has no sense of music. I wouldn’t rewrite his lyrics, out of respect for his idea, but sometimes I’d add or trim a few words to create a rhyme or a beat.”

For “Étonnez-moi, Benoît,” the closest they came to a hit, Courson added one word, two syllables. “The idea of the song,” he said, “started with the famous phrase that Diaghilev said to Cocteau — ‘étonnez-moi,’ ‘surprise me,’ so I added ‘Benoît.’ It’s very simple, but it gave some swing to the song.” And, as a French friend told me, the name suggests just the kind of guy destined from baptism to be slighted by girls. “Étonnez-moi, Benoît” demonstrates the cruelty that ensues when one half of a couple holds all the cards:

Surprise me, Benoît

Walk on your hands

Swallow pinecones, Benoît

Apricots and pears

And razor blades

Surprise me. . . .

Surprise me, Benoît

Cut off your ears

Eat one or two bees, Benoît

Be the sun in my life

Make the alarm clock ring

Surprise me

That the young woman’s demands — some playful, others life-threatening — arrive without pattern or escalation is chilling, even more so when we learn that her only motivation is ennui. “Between you and me,” she says, “it’s crazy how boring it can get.”

The pair’s original thought was that Courson would perform their material as a singer-songwriter, but before he headed to an audition at the star-making radio show Europe 1, Modiano insisted on a name change. “Hughes de Courson is not good for music,” he said. “Call yourself David Stern.” Despite the nom de Jew, the tryout was a flop, but Modiano’s mother and her showbiz connections managed to get them an audience with Francoise Hardy, whose own debut album had sold a million copies. Hardy recorded “Étonnez-moi, Benoît” in 1968, the same year Modiano published his first novel. Soon, the song was blasting from radios in the voice of France’s favorite starlet.

Courson estimated that they composed fifty to sixty songs in all. Half a dozen were recorded by icons such as Hardy and Régine, who is credited with inventing disco, and one by the folk singer Myriam Anissimov, who had a brief affair with Modiano. Another nine were included on Fonds de tiroir. Like “Étonnez-moi, Benoît,” the songs on their album are dark but never dreary, invigorated by a macabre wit that often bleeds into cruelty. Rather than love songs — there is no more romance in Modiano’s lyrics than in his fiction — they tend toward character sketches, and the characters tend toward the fringe.

In “La polka des grosses dames” (“The Fat Ladies’ Polka”), André Miguel James de la Serna is a professional dancer, paid to fill the dance cards of plus-size ladies at an afternoon tea. Drowning in their arms, he dreams of the days when he worked in “the most beautiful butcher shop in San Salvador.” “Ma lilliputienne” is based on the true story of a diminutive prostitute who worked in Paris during the war. Le Chabanais, a brothel favored by high-ranking members of the Vichy government, installed her in a low-ceilinged apartment in the attic and appointed the room with miniature furniture. In characteristic Modiano fashion, the story is told by a former client, who spots her decades later in a bar on the Rue de Provence, alone in a booth in front of a whiskey. The years have taken their toll, and the woman is “even more of a dwarf.” Still, the john thrills at the memory of asking the madam for the lilliputienne, riding the silent elevator to the top, and crawling into her scaled-down wonderland.

Courson recorded Fonds de tiroir over five sleepless nights in 1979, taking advantage of studio time he had booked to mix an album for Malicorne. Modiano came to the sessions and was delighted with the result, but by 1983, when Courson proposed rereleasing the album on CD, he’d lost his enthusiasm. Modiano’s reputation had grown in the intervening years, and he accused his partner of exploiting his literary fame. “We had an argument,” explained Courson. “I said, ‘Patrick, I will release this CD even if it prevents you from winning the Nobel Prize.’ It was a joke, but I was relieved to see that it didn’t cost him that.” It did, however, cost Courson their friendship. Modiano hasn’t spoken to him since.

Modiano’s apartment was only a short distance away, on the Rue Saint-Sulpice by the Jardin du Luxembourg. Since he is known to walk in the park with his wife and grandchild, Courson and I headed over, agreeing that we’d feign amazement at the coincidence if we happened to bump into him. On our way, I asked Courson about something that had been confusing me since we began our correspondence. According to my research, Modiano and Courson wrote songs for no more than a couple of years, but Courson’s emails to me suggested a lengthier partnership.

As we approached the park, eyes peeled for a very tall man, he confirmed that the two had collaborated for much longer than anyone knew. “I count my friendship with Patrick in wives, and he has met three, which is about twenty years. All that time we were writing songs.”

In fact, he said, some of the songs on Fonds de tiroir weren’t written until just before it was recorded in 1979, which meant that the notion that the songs were artifacts of another time was a Modiano conceit. So was the drawer, photographed on the album cover, in which they “found” the old lyrics collecting dust among the “dried flowers” and the “yellowed photographs.” And, to gild the lily, Modiano composed those lovely liner notes, which conclude: “Yes, the years are running fast. And what to do to hold the time? Maybe try to rediscover in the bottom of a drawer, a bunch of songs which had been drying there for a dozen years.”

Myriam Anissimov lives on the other side of the Seine, in an old Jewish neighborhood in the Marais, long since overtaken by trendy restaurants and shops. Anissimov, who was born in a Jewish refugee camp in Switzerland, acted in plays and sold vintage clothing at a Parisian flea market before emerging as a writer herself — the author of eleven novels and an important biography of Primo Levi. On my second day in Paris, she welcomed me into her cluttered fourth-floor walk-up and had me sample three kinds of tea before we settled down to talk. Since Courson’s portrait of the calculating and mischievous Modiano was so unlike the one found in the media — and since the bitter end of their partnership inevitably colored his recollections — I was curious to hear from another person who had known Modiano as a young man.

Anissimov met Modiano shortly after the release of “Étonnez-moi, Benoît,” which impressed her as “very sadistic, but lovely.” Smitten by Anissimov’s girlish manner, Modiano wrote a particularly wicked song for her, about a child with “tiny little feet and tiny little steps” who ignores her mother’s admonition to beware of strangers and is abducted by a pedophile. After that unusual flirtation, they began a courtship of taxis and dinners and frequent visits to his family home on the Left Bank.

Modiano’s novels often mention this building, where his mother and his father, who was living with another woman, had separate but adjoining apartments. “It was like a palace,” recalled Anissimov, with “parquet de Versailles, four windows overlooking the river, and for Patrick his own section with a room full of books.” Such a grand apartment seemed to contradict Modiano’s claims of poverty — he wrote in Pedigree that a pair of secondhand crepe-soled shoes had lasted him a decade — but Anissimov suggested that he might have been dependent for cash on his father, whose financial fortunes were as erratic as his generosity. In any case, the impression Modiano’s accommodations made on Anissimov was offset by her reception from his Catholic mother. One day, Anissimov told me, she was waiting for Modiano when his mother asked to speak with her. “We are not Jewish,” she said. “Patrick made his first communion. So you have nothing to do here in our apartment. Leave. We don’t want Jews here.”

Modiano’s meeting with Anissimov’s mother didn’t go any better. About a month into the relationship, she arranged a lunch for the three of them at a Jewish deli in the Marais called Goldenberg’s. Her mother, who owned a clothing shop in Lyon, was in town to replenish her merchandise. Anissimov laughed remembering Modiano’s reaction as he saw his potential mother-in-law arrive lugging two heavy bags, and realized she wasn’t nearly as wealthy as he imagined. All through lunch, he pretended to have a stutter. Perhaps, Anissimov said, refilling my teacup, the speech impediment he adopted that afternoon was a precursor to the verbal hesitancy for which he is now known.

It was the second time that someone had suggested to me that Modiano’s timidity was a smoke screen. Denis Cosnard, who wrote a biography of Modiano, had mentioned over coffee the previous afternoon that there is a “real question” about whether Modiano’s behavior is genuine. The charge seemed all the more credible after I saw a French TV interview from 1970 in which Modiano had no trouble expressing himself.

Why the charade? Courson believes that Modiano’s fabrications were compulsive. “Patrick never tells the truth,” he told me. “He always lies, even when there is no reason.” At times, however, the reasons seem clear enough. Modiano tends to present himself in whatever way appears most advantageous. For decades, he lied about his age — even going so far as to doctor his passport — in order to appear like a more precocious talent. As for the backdated lyrics on Fonds de tiroir, Modiano may have tried to recast his songwriting as an adolescent blip so as not to give skeptical intellectuals any more reason to doubt his seriousness as a novelist. But such straightforward appraisals may underplay the role of deceit in his work. For Modiano, evasiveness is strategic, aesthetic, and personal; he seems to be at once in control of his lies and destabilized by them. With his novels, all part of a vaguely autobiographical project, Modiano refracts himself through his characters so that the contours of identity are lost. “I am nothing,” says Guy Roland in Missing Person. “Nothing but a pale shape.”

“When I first met Patrick,” Francoise Hardy told me, “I thought he suffered from mythomania, the passion for telling lies. Now I know him well enough to know that he does not.” At age seventy-two, after a twelve-year battle with cancer, Hardy was still striking. Dressed in black, she was seated on a sleek leather couch at her home on the staid boulevard that rings the Bois de Boulogne, formerly the royal hunting grounds. Hardy became an immediate, if reluctant, sensation in 1962 with the release of “Tous les garcons et les filles.” She has since collaborated with artists as varied as Iggy Pop, Malcolm McLaren, and Blur, and her songs of adolescent longing still pop up on the soundtracks of Bertolucci and Wes Anderson films. Over the course of our interview, which included references to astrology (“Patrick doesn’t behave at all like a Leo”) and graphology (“His handwriting is very elegant and clear. He is not someone who hides things”), Hardy was protective of Modiano.

I asked whether she was troubled by the cruelty of “Étonnez-moi, Benoît.” No, she said. It just made her laugh. “ ‘Cut off your ears.’ I thought it was very funny.” As for the abruptly aborted friendships, she was disturbed and confused by what I’d heard from the others, and attributed their comments to the grudges of those left behind. “Maybe Patrick was sick of them for a long time and too nice to say it.” She glanced over at a large brass statue of a Hindu goddess that stood nearby. In her own experience, she said, the best way to get rid of people is to move.

Hardy was the only person I spoke with who was still in touch with Modiano, and, perhaps not coincidentally, the only one more famous than he is. As we faced each other in her elegant apartment, she recalled an occasion on which Modiano shared his expertise in misleading interlocutors. Hardy was being featured on a German television show and the producers were pressuring her to serve up an anecdote about her past, so Modiano offered to make one up for her. Following his script, she told the interviewers that she and her best friend had met at the funeral of their common nanny, who had nursed them both as infants. Afterward, whenever Modiano sent her a first edition of one of his books, he signed it, “Your milky brother.”

When I got up to leave, Hardy quoted another songwriting duo, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, as she observed “what a drag it is getting old.” For years, she has lived apart from her husband, the singer Jacques Dutronc, and she suggested that her connection with Modiano was based on a shared understanding of loneliness. “My first success was a song about how ‘nobody loves me,’ ” she said, and remarked that many of Modiano’s lyrics also contemplate solitude and its toll. Perhaps that explained why they got along so well, but she acknowledged, in a phrase that might have come from any Modiano novel, that “it’s very difficult to know anyone.”

The day before I left Paris, I joined Courson for a second early-morning walk. It was the coldest day of a cold week, and he was hatless and underdressed in a loose-fitting overcoat that was stained with makeup and blood from an incident involving Assana and a waiter. We climbed Montmartre and turned left on the Rue d’Orchampt, where the walls of the more imposing homes were covered with graffiti, and made another left onto the Rue Lepic. At the corner, a small poster for the hacker collective Anonymous peered down at us like a discreetly placed camera. Courson said he used to walk here at night with Modiano, who kept a list of the houses with double entrances so that, in a pinch, he could slip in one door and out the other.

“ ‘On sait jamais,’ Patrick would say. ‘You never know . . . if there is a gang and they take the Jews.’ Patrick is not Jewish, because his mother is not Jewish, but he feels Jewish. And at the same time not completely Jewish.”

It seemed like a good time to mention that I was Jewish.

“It’s okay,” Courson said. “Nobody’s perfect.”

Modiano’s contorted relationship to his half-Jewishness is the most provocative thing about him and his work. His focus on the predicament of Parisian Jews during the occupation has earned him a place in the canon of Holocaust literature, yet his characters are rarely identified as Jews, and, for the most part, he doesn’t identify as one, either. Early in his career, before he became Nobel material, Modiano probed his fraught heritage through a fascination with the Gestapo and writers on the French far right, such as Pierre Drieu La Rochelle and the Hussards. Scholars of Modiano in France have written about this fixation, but it’s rarely mentioned in popular reviews of his work, which often acknowledge his father but prefer to tread lightly on such uncertain and uncomfortable terrain. Anissimov described the young Modiano’s obsessions as a kind of mania. “When I met him,” she recalled, “he looked like a disturbed person. We wandered the city all night. He wanted to show me all the places where the Germans tortured people, the Gestapo places. And when he came to the house, he would start speaking German and calling out, ‘Heil Hitler!’ ”

Articles about Modiano often refer to his collection of telephone books from before the war — sometimes a name or an old address provides a starting point for a novel — but according to both Anissimov and Courson, Modiano used those same research tools to place late-night prank calls, which can’t be easily dismissed as juvenilia. One call that still troubled Courson was to a man who’d been involved with the Gestapo and later became a food critic for a local paper. “Patrick claimed he was too much of a coward to do it himself,” said Courson, “so I phoned and said, ‘We found you. We’re going to kill you.’ The guy was a bastard, yes, but it was horrible, very cruel. I’m ashamed of having done that.”

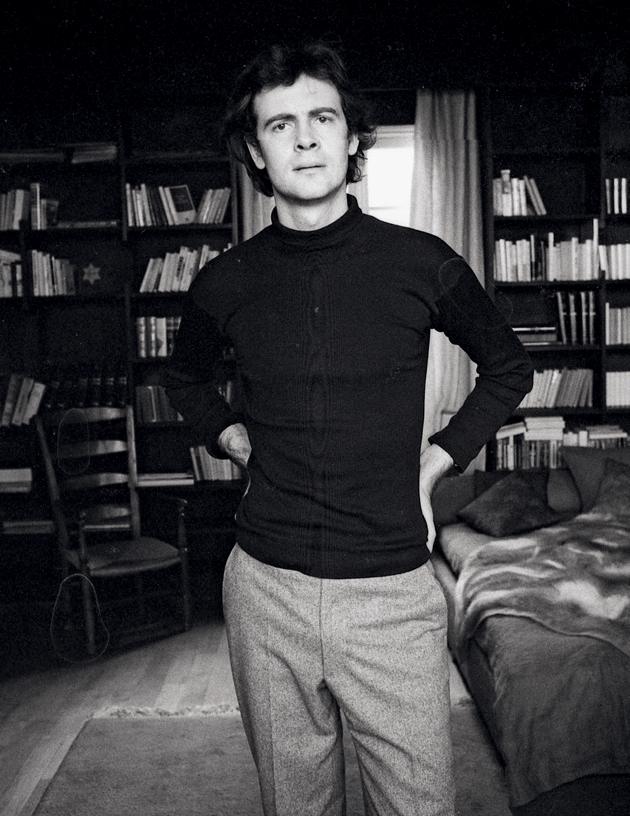

During the 1970 interview, the journalist asks the young Modiano about his “identification with the aggressor.” Modiano, buoyant and handsome in a black turtleneck, replies:

Once there is someone who wants to kill you or hurt you, it is more interesting to try to talk with him and try to distract him by doing a little dance so that he’ll forget his first idea, which was to assassinate you. So you have a little fun with him and little by little you can even talk as he talks . . . and then in the end you might become the best friends in the world.

Such a friendship is on display in La Place de l’Étoile (The Place of the Star), Modiano’s frenetic first novel, whose title refers to both the Arc de Triomphe plaza in Paris and the yellow star that Jews were forced to wear during the occupation. In the book, Modiano works through his conflicted feelings toward his Jewish father in a style that both channels and parodies Céline, giving voice to the most hysterical strains of French anti-Semitism. Raphaël Schlemilovitch, a Jewish screenwriter of the postwar generation, joins the Gestapo in Geneva and becomes Eva Braun’s lover, undergoes reeducation in an Israeli kibbutz, and reconnects in New York with his father, who is depicted in a way faithful to every anti-Semitic stereotype. Schlemilovitch writes a play that ends with a son torturing his father, the son sporting a Gestapo trench coat over an SS uniform and the father in skullcap, sidelocks, and beard. Cosnard notes in his biography that later editions of the book cut passages “to soften attacks” on Modiano’s father, which might be read as “too anti-Zionist.”

La Place de l’Étoile is an anomaly among Modiano’s novels. Soon after its release, he began to move toward the sober, unadorned style for which he is known, and for that reason — as well as the book’s strange familial and religious dynamics — La Place de l’Étoile has not received as much attention as his later works. Its adolescent energy, however, would not surprise someone familiar with the songs — the callous bullying of “Étonnez-moi, Benoît” or the depravity of “The Good Children’s Cocoa,” a lullaby in which well-behaved youngsters are rewarded with packets of cocaine left on their nightstands. Only in La Place de l’Étoile can one glimpse the Modiano that Courson and Anissimov remember, where the light yet vengeful tone of the songs finds a match. Modiano’s lyrics help recover that image of the young author, the mercurial and aggressive protagonist of this early book, and a period of fitful self-discovery that he has deliberately and carefully left behind.

To give ourselves a destination, Courson and I headed toward Modiano’s former home on the Rue de l’Armée d’Orient, and soon stood in front of an imposing three-story house with a private garden — a gift from his wife’s father, Bernard Zehrfuss, a prominent architect who designed the European headquarters of UNESCO. “Patrick always said he had to marry a rich girl,” Courson said with a wry smile. “But he loves her very much.” Near Parc Monceau, where, as young parents, Modiano and Courson walked with their children “like normal people,” he pointed out a large house that he was quite sure was Modiano’s second home, although he conceded it could be another one that looked just like it.

As we circled back toward Montmartre, Courson was reminded of the last song he and Modiano wrote together before they became estranged, called “Ne reviens jamais” (“Never Come Back”). Ironically, it’s a breakup song, whose narrator describes how much she relishes her freedom with her boyfriend gone. Over the years, Courson has considered releasing “Ne reviens jamais” with no name attached to the lyrics, so that Modiano, if he wanted, could contact him to claim credit. Modiano has written that he does something similar in his fiction, giving characters the names of people with whom he has lost touch in the hope that they might reach out, although he says it has never happened.

The early-morning streets were quiet and empty, and as Courson talked about the song, it was clear that he was still hurt and mystified by the sudden end of their friendship. “One day I will run into him on the street and he won’t reject me,” he said, “but he will never answer the phone.”