I was present when someone asked the poet Sophocles: “How’s your sex life, Sophocles? Can you still make love to a woman?” “Shush, man,” the poet replied. “I am very happy to have escaped from that — as happy as a slave who has escaped from an insane and heartless master.”

— Plato, Republic

Bergama, that autumn afternoon. We walked through the sort of streets that tourists don’t usually see, the sort of streets where noisy schools are and no one notices the lemon trees.

That is where it started, this episode. In Bergama.

I am sixty-two years old, a professor of philosophy at a famous university.

You are fifty-eight and also a member of the faculty, the author of several works on the terminology of Plato.

We have known each other for many years.

You are a widow.

Your husband died two years ago — or is it three now? Two or three.

Since then, since he died, we have holidayed together a few times. And they have been very pleasant, those friendly holidays we have taken together. Aquileia and the Venetian hinterland. (That was the first, not so long after your husband’s disappearance in the sea, and sometimes I found you in tears, sitting on a bench under cedar trees.) Walking in the Alps. (That day, above the Lauterbrunnental, that we saw the Brocken specter . . . ) And now here — the Aegean shore of Turkey, and the Greek islands lying off it, lying there in the sunset every evening. It was your idea to come here. I did not question it. You used to come here often, I know, with your husband, and if I wondered what he might have to do with it, I did not ask. We do not usually talk about that sort of thing.

We flew to Istanbul and, after a day or two there, set off down the shore of Asia Minor, stopping to see the major sights.

And so we came to Bergama.

We were accustomed by then, since our Alpine walking trip, which had included stays in several rustic berghütten, to amicably sharing a room. It saved money, and it seemed silly not to. What we had never done, until that night, was share a bed. So when the man led us up the narrow stairs of the only passable hotel in Bergama to what he said was the only vacant room he had, there was, naturally, some hesitation, some umming and ahhing.

Finally you said, “I don’t mind. The bed’s big enough.”

“Okay then,” I said.

And the man handed me the key and left us alone.

We had dinner in a local restaurant a few streets away, under harsh fluorescent lights and a television showing a soccer match.

And then back to the hotel, and up the stairs to bed — and strange to go to bed in the same bed, but no mention made of this.

Reading in silence.

And you just said, “Night, night,” and turned over.

And I lay there reading for a while (a new translation of the Symposium that I was supposed to be reviewing) and then turned off the light.

I did not sleep well that night.

There was a fan heater blowing tepid air that kept stopping and starting. You were lying there silently. And I was very aware of you lying there — more aware than I had anticipated. I was able to feel the warmth of you, which somehow stopped me from falling asleep for a long time, and when I finally did it was a light sleep from which I often woke with a strange tense feeling, aware of your warmth and weight, and then I would slip under again, and wake again and momentarily forget where I was and that you were there, and that kept happening until finally light started to define the small windows — one yellow, one blue. They slowly filled with light. The whole room slowly filled with light, and then you were sitting on the edge of the bed staring sleepily at the light-filled room, and taking your watch from the table and looking at it to see what time it was, and yawning.

“What time is it?” I asked, to show that I was also awake.

“Seven,” you said.

We decided to stay another night in Bergama. You were something of an expert on the Hellenistic civilization whose wreckage was strewn on the hillside there. The previous afternoon we had taken only a quick preliminary look at ancient Pergamum. Today we would study it properly. You would be my guide, you said. We were having breakfast downstairs in the hotel. I took a sip of gritty coffee and nodded. “Sure,” I said.

At that point the hotelman came up to our table and told us that he had a twin room free now, if we wanted to move to it. There was no question of us not moving, of course. Why would there be?

You made the arrangements while I sat there spooning honey onto some bread.

The twin was downstairs and darker and damper. The walls in a constant cold sweat. The bathroom cavelike where I masturbated miserably late that afternoon, for the first time in I don’t know how long, while you were at the women’s hammam.

When you got back, still flushed and glowing, with a damp towel in a plastic shopping bag, I was sitting there with my book.

“How was it?” I asked.

“Very interesting,” you said, and you told me about the talkative local women you had shared the hammam with, and the way they had shaved themselves so unselfconsciously while they asked you about yourself, where you were from, what you were doing there, who you were with. You said you were there with a friend. A friend? they asked. A woman? No, you said, a man. They laughed skeptically at that, you told me. A man? they said. How can you be friends with a man?

I just smiled.

Your hair was wrapped up in a sort of turban, which you now unwound. You had dressed while your body was still hot, and patches of sweat, I noticed, were visible on the smoke-blue fabric of your shirt.

The next day we went on to Ephesus.

And yes, something was troubling me. I kept thinking about the night we shared a bed in Bergama. Something about that. It had started with an almost imperceptible whisper of disappointment when the hotelman had told us, the next morning, that he now had a twin available if we wanted it, and you had looked at me with this look that said, unequivocally, “We want it, right?” And I, putting down the coffee cup and taking up the honey spoon, had nodded slightly, and you had started making the arrangements while I spooned honey onto my bread.

I was able to dismiss the feeling while we walked around the ruins that day, but it was there again when we checked into a modern hotel in Izmir the following afternoon — a twin room, high up, with windows that wouldn’t open. We had spent the day at Ephesus and were tired. While you showered, I sat on my bed and listened to the teasing sound of the shower and to the muted hooting of the traffic far below. It had by then started to seem to me that in letting that night in Bergama pass so uneventfully, I might have in effect been telling you something — something that possibly wasn’t true.

That was not how it had felt at the time. Only later did I start to wonder whether I had been somehow not entirely straightforward. I mean in the way I had kept so scrupulously to my half of the mattress, in the way I had shared the bed with you as I would have shared it with a man — taking pains, that is, to avoid any kind of even accidental physical contact, no matter how slight and insignificant. That, it seemed to me now, still thinking about it as we waited the next morning in Izmir for the lift down to the lobby, had not been entirely sincere, that apparent actual aversion to physical contact.

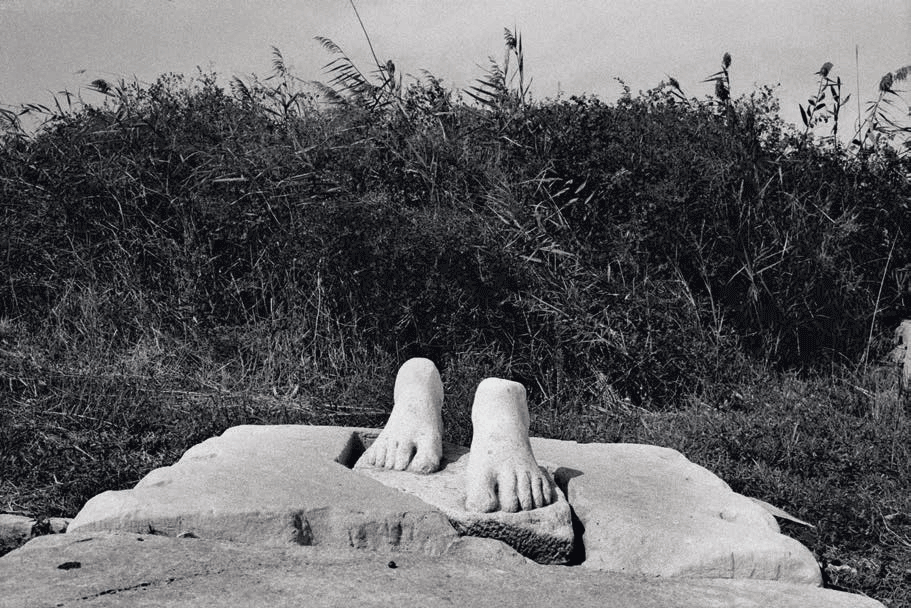

Over the course of the day, these feelings developed further. It started to seem to me that I had let that night in Bergama somehow slip away — hardly sleeping, lying next to you, I had let the whole night slip away, until the light appeared in the windows in the morning and you were sitting on the edge of the bed with your hair loose and looking at your watch and seeing that it was seven o’clock. Yes, I had let it slip away. And would there ever be another like it? Another night of such physical proximity. Another opportunity to express the desires I seemed to have, to be at least less insincere about them than I had been then — though whether I had even had, in Bergama, the desires that I seemed to have now, as I walked with you through the archaeology museum in Izmir, looking at the greenish bronze bodies of boys and girls, I could not really remember.

What I wanted, more than anything, was another chance, another night like the one in Bergama.

In the meantime, I tried to enjoy our holiday — to take an interest in the streets of Izmir or the Temple of Artemis — though that was becoming more and more difficult, since I was now very preoccupied with the sleeping arrangements. Each new twin room was a secret disappointment.

And what seemed extraordinary to me, as the days passed, was how little I had valued that night in Bergama at the time. It seemed uniquely precious now. And I had failed even to know it for what it was.

We decided to leave Turkey and spend some time in the Greek islands of the eastern Aegean. You knew them well. You had been there many times with him — your husband. We would take a ferry, we decided, from Kusadas? to Samos.

It was already evening when we arrived in Kusadas?, so the plan was to spend the night there and take the ferry in the morning.

There was an unpromising little hotel near the ferry port — that seemed to be the only option. We went in. The woman told us that she had only one vacant room. She took us to it. Narrow corridors painted dark blue. “Okay?” she said tiredly, as we peered in from the doorway.

We both sort of nodded.

Nothing was said about the double bed as we brought in our bags.

I had noticed, that night in Bergama, that you sleep mostly facing left, and I deliberately took the left side of that bed in Kusadas? so that we would sleep facing each other. Did you notice that?

Of course you didn’t.

You were unpacking, putting your things in the dingy bathroom, with its plastic sliding door.

Later we had drinks on the roof terrace. There was a roof terrace, with candles and fig leaves and views of the harbor. I was unfortunately too nervous to enjoy those things. The night loomed. And suddenly all the promises I had made to myself since the night in Bergama, of what I would do if I somehow had another opportunity, seemed almost insane, and I felt only this kind of numb void inside me where I had thought definite desires had been. We were sitting in low chairs. A single candle flame glowed on the table, surrounded by shadows. You were talking, asking me things. I must have seemed very distracted, as though my thoughts were far away.

And the whole evening passed like that.

And then I was in the dark, overwhelmingly aware of your presence, your warm physical presence, lying near me on the smallish double.

The clock of the wall-mounted TV shed a faint orange light.

You were asleep, I think.

I lay there.

I lay there.

And every second that passed was me thinking, I’m just lying here. I’m just lying here.

At first the night seemed endless.

And then it was nearly over.

It was dawn, the windows were starting to appear, as they had that night in Bergama, and in a state of total nervous exhaustion and in fact despair, as this night, like the night in Bergama, seemed about to slip away forever and irrevocably, I put my hand on you. Turning over, as if asleep, I tore my arm out from under the quilt and let my hand fall onto you, somewhere near your hip, I think. You were lying on your side facing away from me and, my heart thudding insanely, I let my hand fall onto you, and left it there.

When it first fell onto you, you seemed to try and twitch it off, but then you let it lie there, as the minutes passed, one after another, and the light hardened in the windows and my heart thundered away. You let it lie there. That’s what I thought, in that state of almost hallucinatory agitation and fatigue — that you were aware of it and allowing it to lie there on your hip.

And that was enough for me.

I did not have any illusions that anything more would happen, not that night anyway — that my hand lying on your hip would lead to anything more. I did not think it would. And it did not. It was, in that sense, an end in itself. And I had had to force myself to do even that. I had had to force myself, with a painful, despairing act of will, to put my hand on your hip, because pushing against the desire I had to touch you and not to let the night simply slip away as I had in Bergama was something equally powerful — something more vague, more profound than mere fear of rebuff: an immense and mysterious sense of prohibition, in the face of which that diffident and deniable hand felt like something hugely significant.

Yes, I’m sorry to say that that was how it felt to me, lying there in the pale gray light.

Like something hugely significant.

Later that morning, downstairs in the hotel dining room, I was not as sure as I had been at dawn, lying perfectly still in the bed with my eyes open and my hand on your hip, that anything of significance had happened.

It did still seem possible, though, that something significant had taken place — that you had allowed my hand to lie there, for half an hour, and that that was not without meaning.

I tried to hold on to that possibility.

Your extreme normality, however, worked to undermine it. The more normal you were — and you were very normal, leafing through your Rough Guide to the Greek Islands over the olives and sheep’s cheese and yawning — the more normal you were, and the less your demeanor suggested that anything significant had taken place, the more taciturn and irritable I became, until we found ourselves making our way to the ferry port in an atmosphere, I thought, of froideur and tension, though of so subtle a kind that it was impossible to say whether or not I was just imagining it.

We did not speak much anyway.

We embarked for Samos that morning in silence.

And arrived two hours later at the little harbor — which was as one would picture it, tucked into a kink in the island’s shore, very pretty, white houses on hillsides. The air was warm and the sky hazy.

We had a very late lunch in one of the few restaurants that was open, with our luggage next to us. I picked at squid and deepened my sleepiness with sour white wine.

When we left the restaurant the afternoon was already well advanced, and we started to look for a hotel. You had spent most of the meal turning the pages of your book, your Rough Guide to the islands, and had found one you wanted to stay in.

We looked for it. There was, very palpably, a feeling that the season was over. A somnolent quiet over the whole settlement. We found the hotel and were shown a room.

Twin beds.

I said I didn’t like it.

I wanted another double, you see. I had come to the painful conclusion, as the day went on, that very probably nothing significant had happened the night before, that you had been asleep the whole time and had not even noticed my hand on your hip. So I wanted to do something like that again. I wanted something significant to happen.

You were still surveying the twin room we had been shown. Fortunately it was not actually very nice — though you would have taken it, I think, if I had not been so against it. You were tired and just wanted to settle somewhere, to put down the suitcases and have a shower.

“I don’t like it,” I said again, in a firm voice, ignoring the fact that the woman who was showing it to us was standing there.

I turned away.

You sighed and apologized to the woman and said we would look at some other places and maybe come back later.

She said she didn’t know if any other places were open.

We left the hotel and started walking again, pulling our suitcases, along the waterfront. Most of the hotels were not in fact open. And you were now impatient to find somewhere. You were almost stroppy.

Finally we found another place, quite an elegant, expensive-looking place, slightly up the hill, among mature cypress trees.

In the lobby I said to the smart young man that we would like a room, “with two beds if possible.” You were standing there — I had to say it. It was what you always said, when you did the talking, and it was what you thought I wanted, too.

The smart young man said he only had doubles. At this my heart started to thump more quickly. “Ah,” I said. “Well . . . ”

And then he offered, to my dismay, to put a second bed in one of them.

As soon as he said that I went from very much wanting to stay there to very much not wanting to stay there. Looking for a way out, I asked him the price, and when he told me, I immediately said it was too much. He said he might be able to do something on that, and insisted we look at the room. I started to tell him, again, that it was too expensive, and then you said, speaking at last, “We might as well look at it.”

We followed him to it, and it was lovely. There was a fireplace, and he told us that a fire would be made if we took the room.

We stood there looking at it, in the diffuse daylight of the autumn afternoon.

And then you asked again whether it would be possible to put in a second bed — you made sure that that was possible, you made absolutely sure — and when you had established that you said, “I think we should take it then.”

And I said, suddenly in pain, suddenly in a sort of darkness as I understood definitively that what had happened the night before had had no significance whatsoever — or not in the way that I had hoped it had, perhaps in another way, the opposite way, and I said, hating that place now, the site of my bleak realization, that romantic room, “I think it’s too expensive.”

And the smooth young man, still standing there, lowered the price.

And you said, impatient now, “Fuck it, let’s just take it.”

And I said, without enthusiasm, in pain, “Okay.”

There was something about the way you had insisted on the second bed — insisted on it. It made me think that perhaps you had not actually been asleep the night before, as my hand lay on your hip. It made me think that you had been awake, and aware of my hand, and not welcoming it, trying to ignore it, not wanting, having tried initially and instinctively to twitch it off, to make an actual incident out of it perhaps, or thinking innocently that I was asleep and unaware of it myself, and you just lying there, waiting for me to move it, and hoping I would do so soon, and very much not wanting anything like that to happen again.

I was in the bathroom — I needed to be alone with my misery — when the second bed arrived. And I heard you say, “No, not there,” to the man who wanted to put it next to the canopied double that the room already had. I heard you say, “Over there,” and heard him pull the folding cot across the floor to the farthest corner of the room, where you were directing him to position it. I heard it all. Standing in the bathroom, I heard it all. And it was as though you knew that I was listening and were trying to hurt me — or that is what I felt at the time.

When I emerged, the man was gone and you were in possession of the double, writing in your diary.

I sat on the sofa so desolately that you said, after a while, looking up from your diary, silencing for a moment the quiet scraping of your pen, “Are you all right?”

I was very obviously not all right, and totally unable, for once, to hide it.

“What’s the problem?” you said.

And unable to tell you the truth — how could I tell you the truth? — I said I just didn’t like it there and wished I were at home.

You stared at me for a moment or two, sort of coldly. Then the scrape of your pen started up again.

I said, a few minutes later, “Don’t worry. I don’t really wish I was at home.”

And you said, “I wasn’t worried.” And then, “I don’t worry about your state of mind. I don’t want it to infect me, that’s all.”

We were drinking whisky — the Glenmorangie we’d found for sale in the duty-free shop of the tiny ferry terminal in Kusadas?. I was swilling it down, taking it for the pain, while you sipped yours.

And you had somehow, through some question you asked, provoked me into saying that I thought that life in this world was just a miserable, lonely struggle, and then it was over. There was no such thing, I said, as love . . .

“You don’t believe in love?” you said, sounding no more than vaguely interested as you sipped your whisky.

“No, I don’t,” I said. “Why are we so obsessed with it? Why do we think it’s impossible to be happy without it?”

“Is that what we think?”

“Isn’t it?”

“Are you happy?” you asked.

I said that I didn’t know anyone who was happy. “Do you?”

“It depends what you mean.”

“Do you?” I insisted.

And I saw the shadow pass over your face.

I downed the whisky in my glass — a dinky tumbler from a shelf over the sink, a shelf with doilies and a bar of soap wrapped in shiny paper.

He was happy, wasn’t he? Him. Who drowned. Never found. That was what you were thinking. He was happy. Yeah, Mr. Happy.

You looked down, lowered your face.

I love you, I wanted to say.

Never found.

Shhh.

“Don’t listen to me,” I said, drunk now. “I’m just depressed.”

You were writing again. “Okay,” you said, without looking at me.

And then a man appeared, smiling, to light the fire.

And if I had said, “I love you,” what then?

What would you have said or done?

You might have laughed, from the sheer shock of it. From the sheer I-don’t-know-what-to-do-with-that-ness of it.

“Oh,” you might have said.

And then what?

After the silence, the shock, after you had told me not to say that, or not to be silly.

You would have said, probably, that we ought to have separate rooms then. Or even that you thought perhaps that we ought to end this holiday, since it wasn’t what you thought it was.

I sloshed more Scotch into the mini tumbler and snuck a furtive look at you. You had stopped writing, your pen had fallen silent again. Your head was still bent over your diary. The end of the pen was in your mouth. I knew whom you were thinking of, sitting there in the shadows of the canopy bed. (The light from the window was muted and bruised. The afternoon was darkening. Rain clouds, swollen and purple, were gathering over the island.) You were thinking, still, of him.

When I was divorced, nearly ten years ago, already well into my fifties, I had hoped that I would never have to feel things like this again. That I would never again have to experience, as I entered the autumn of my life, this sort of desire. This sort of helpless perplexity. This madness.

When will it end, this madness?

Is there an end to it?

We spent only a day on Samos.

There did not seem to be a lot to see on that island. We were unable, anyway, to muster much enthusiasm for it. I felt a sort of listless indifference for everything, that day. Apatheia. We looked at the ferry timetable. There was a boat to Patmos in the early afternoon. You suggested we take it.

We waited on the windy quayside.

You looked tired, as if you hadn’t slept well.

The ferry, arriving from Chios, was late, and when we finally embarked we found it nearly empty.

It is hard to imagine anything more dated, more superannuated, than the interior of that small ferry, where we spent several hours sitting on plastic seats surrounded by chipped wood-effect veneer and the ingrained odor of decades-old cigarette smoke. The windows were milky. The toilets discolored. The door to the deck croaked when I hauled it open. We had spent most of the voyage inside because of the rain that was coming down steadily in the eastern Aegean that day.

Now, as we neared Patmos, I ventured out and found myself in a fine drizzle as the boat blustered through the green waves.

(You had fallen asleep, nodded off half-curled-up in one of the plastic chairs, your head leaning against the veneer, with your book still held precariously in your hands.)

I stood on the deck, blasted by the wet wind. The island was visible.

Just a shape, a silhouette.

That clarified, eventually, into austere hills.

I watched them for a while. Windswept moorland was what they looked like, without obvious beauty, sloping undramatically from the sea, like the highest points of an otherwise flooded landscape.

The ferry docked and we disembarked.

We took an apartment for two nights — two bedrooms, and a living room with some kitchen things in one corner. From the bedroom windows you could see the sea. I had experienced, as we trudged up the stone steps behind the woman who was showing us the place, a flutter of the tension I was so used to at those moments — the sleeping arrangements, what would they be? So when she said, “There are two bedrooms,” I was surprised to feel something more like relief than disappointment. Two bedrooms. That did seem like the best arrangement, though they were pretty bare, those bedrooms — designed for summer, not for this autumn weather.

The next morning it was raining again, tipping it down with a biblical intensity. At about ten, we took a taxi up to the Monastery of St. John the Theologian — that’s the attraction here, that’s what there is. The Monastery of St. John the Theologian. Visible from all around, it looks like a fortress on the island’s highest point.

The interior of the taxi was warm and damp. The seats felt spongy, and the windows steamed up as the machine struggled with the steep roads. I was sitting in the front next to the driver, the meter ticking untrustworthily near my knee. You were sitting behind me, and I was able to see you in the wing mirror sometimes, the way you stared out the window through the bright beads of rain.

Up at the monastery there was, needless to say, no one about. No tourists except us. Only the odd hirsute monk, skulking in a black gown on the fringes of the public areas — the drenched courtyards, the rooms full of artifacts in glass cases, the cavelike chapels that were almost cozy with hundreds of burning candles illuminating the faces of stern-looking saints. Almost cozy, but not quite — the doors stood open, and the sound of rain on stone trickled into the candlelight, and drafts scattered the weak heat of the massed little flames.

A young monk was standing on duty in one of the chapels we looked at, keeping an eye on it like a museum attendant. He was extremely young, hardly into his twenties, his beard very much a work in progress. I wanted to ask him what he was doing there at his age. I didn’t ask him, of course. He noticed me looking at him and seemed embarrassed. I nodded and left, stepped out into the courtyard as a bell started up somewhere close by, clanging raucously. I had lost you. We had gone into the chapel together and you must have left without my noticing.

I found you in a room full of medieval silverware and Byzantine Bibles. You were standing at one of the arrow-slit windows and looking at the sea, spread out grayly under the sky. Flecks of white flickered on the surface of the water, which seemed to be in motion, to be traveling, to be endlessly on the move, in search of something.

Not wanting to take you by surprise — you had not noticed me — I started to look at the stuff on display.

And then you were there, standing at my side.

“Should we go?” you asked.

We phoned for a taxi — there was a number stuck to the hood of a pay phone just outside the monastery entrance — and a few minutes later the same brown cab that had taken us up there reappeared and took us down again, through the rainy villages to Skala. We decided not to stop off at John’s Cave, where the author of Revelation is said to have had his visions. Instead we sat in a taverna near the harbor and had lunch and then walked back to the apartment.

It had stopped raining.

The light was white and clear and quite cold.