Samuel Donkoh had just turned ten when he began to slip away. His brother Martin, two years his senior, first realized something was wrong during a game of soccer with a group of kids from the neighborhood. One minute Samuel was fine, dribbling the ball, and the next he was doubled over in spasms of laughter, as if reacting to a joke nobody else had heard. His teammates, baffled by the bizarre display, chuckled along with him, a response Samuel took for mockery. He grew threatening and belligerent, and Martin was forced to drag him home.

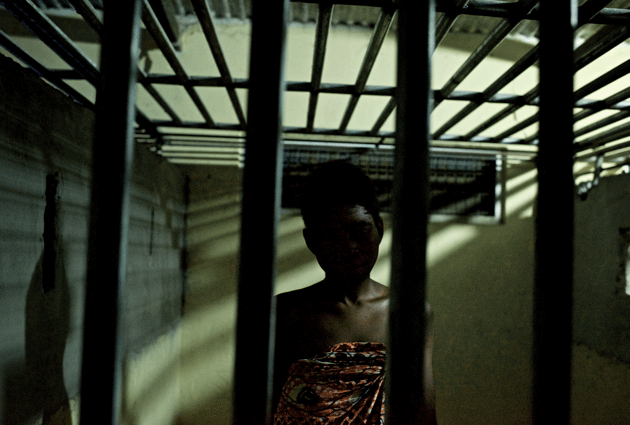

Samuel and Martin Donkoh at the Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital, in Ankaful, Ghana. All photographs by Robin Hammond/NOOR

The episode marked the onset of a frightening metamorphosis. Martin couldn’t understand what was happening to his brother, for although he had seen many abodamfo (“mad” men and women, in the Twi dialect) on the streets, the conventional wisdom was that such maladies afflicted only those who deserved it — excessive drinking or drug use was a popular explanation — or were otherwise spiritually or morally compromised. Samuel, the sensitive, well-behaved son of devout born-again Christians, did not fit that mold. Yet over a few short weeks, without any apparent cause, his condition devolved into ever more unsettling and erratic behavior, punctuated by drastic mood swings and hallucination-induced fits of anger. Martin looked on helplessly. Satan’s demons, he concluded, had seized his brother. He pleaded with God to bring Samuel back.

That was in July 1998. The boys, who lived with their family in Tema, an industrial port city in southeastern Ghana, were on holiday from school and were almost never apart. “Before Samuel fell sick, we were doing everything together,” Martin told me when I met him last summer. They read books together, did their homework together, went to church together, and stayed up late together to watch their favorite soccer team, Manchester United, on television. They looked strikingly alike: both skinny, on the shorter side, with earnest, serious eyes. On those rare occasions when one ventured out alone, into town or to the crowded market where their mother, Agnes, worked as a petty trader, he was often mistaken for the other. Later, after the illness struck, Martin sometimes found himself the recipient of taunts and epithets intended for his sibling.

Samuel suffered worst at night. He would wake up screaming, pointing to venomous snakes and rats that weren’t there, yelling at the voices he said were tormenting him. Soon they were goading the ten-year-old to hurt himself. Their father, Anthony, a supervisor at a nearby textile factory, believed that the outbursts could be disciplined out of his son. “He was very quick-tempered,” Martin said. “Whenever he became harsh with Samuel, my mom had to intervene to stop him.” When the symptoms were most acute, Agnes would cradle her son and recite Psalm 35:

Contend, Lord, with those who contend with me;

fight against those who fight against me.

Take up shield and armor;

arise and come to my aid.

Lord, you have seen this; do not be silent.

Do not be far from me, Lord.

Awake, and rise to my defense.

The martial language was not incidental: Samuel, as terrified and confused as the rest of the family, was plainly under some sort of attack.

When the holiday concluded, Martin returned to school by himself; Samuel’s education was effectively over. Agnes stopped working so she could care for her son at home. But it quickly became clear that this arrangement was not sustainable. The Donkohs lived in rented rooms in a large compound house, whose kitchen and bathroom facilities were shared by all the tenants. The close quarters seemed to exacerbate Samuel’s agitation; it wasn’t long before he was destroying their neighbors’ property, disappearing into town, even defecating in the house’s common areas. Word crept out about a dangerous boy at loose in the neighborhood.

His parents, fearing eviction and worried about his safety, tried keeping him inside. But he still managed to escape. One evening, a group of men approached the house, dragging Samuel, crying and badly beaten, behind them. The men demanded reimbursement for a windshield they said he had smashed to pieces. Samuel, for his part, couldn’t grasp why the men had hurt him.

What was to be done? The approach advocated by members of the Donkohs’ church — prolonged fasting and that brand of combative, focused prayer known as spiritual warfare — had brought little respite, but pursuing a medical route seemed fraught as well. Two of Agnes’s aunts had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, and repeated stays at Ghana’s largest mental hospital, in the capital, Accra, had not helped them. Infamous for its chaotic atmosphere and rampant abuse, the hospital, built in 1906 by the British colonial regime as an asylum for the criminally insane, had rather aggravated their situation. One aunt died alone, a vagrant outcast; the other subsisted on the margins of her hometown. Agnes resolved that a similar fate would not befall Samuel.

A family friend suggested a drastic course of action. He urged them to seek treatment at Nazareth Prayer Centre, a distant religious retreat, or “prayer camp,” renowned as a place where people struck with madness could be cleansed of the demonic forces holding them captive. Spurred by the Pentecostal revival that swept West Africa during the 1990s, these rural camps — some of which allowed families to stay for months or even years on end — had come to serve as alternative sites of care in a region where health services, particularly mental health services, were notoriously scarce and underfunded. The camp seemed to promise the two things Samuel needed most: a spiritually intensive form of treatment, on the one hand, and protection from his self-destructive impulses, on the other.

Agnes balked at the friend’s advice. Moving to Nazareth, located in Akim Akroso, in Ghana’s Eastern Region, would require uprooting not only Samuel but her other children too — potentially costing them their friendships, their stability, their educations. She kept trying to manage at home, until, in early 1999 — almost eight months to the day after Samuel’s first attack — her eldest daughter, Philomena, a shy, mild-mannered twenty-year-old, who had recently apprenticed to become a seamstress, plunged into a similar state. The malevolent voices, the hallucinations, the strange, often combative inclinations: there it was all over again, like a virus spreading from one member of the household to another.

“We wondered if God forgot about us — if he’d forsaken us,” Martin said. Some relatives, conscious of the social disgrace and financial burden of mental illness, recommended a quick solution: take Samuel and Philomena to the hospital, leave false contact information with the staff, and move on with their lives. For Agnes, abandoning her children was inconceivable. Yet continuing to look after them at home had become impossible. She traveled to a regional medical clinic, hoping for guidance, but the doctor she saw had little to offer. He referred her to the psychiatric institution in Accra and provided no further assistance or instruction.

On August 18, 1999, Agnes and her children left behind their lives in Ashaiman and departed for Nazareth.

When Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s founding prime minister, assumed office in 1957, he had ambitious plans for his country. A number of his grandiose designs for an “industrialized socialist society” came to fruition, but most did not. Among the discarded projects was the Pan-African Mental Health Village, a cutting-edge experiment in a kind of therapeutic collectivism. Outfitted with a cinema, a supermarket, and a surgical theater, the village was conceived as a tranquil place where the mentally ill and their families, free from societal strains and prejudices, could live and work alongside leading clinicians. But Nkrumah was overthrown in 1966, and construction was halted. At the time of his death, six years later, the quarter-finished Mental Health Village was already falling into decrepitude.

For the succeeding generation of mental health advocates, these crumbling, deserted buildings represented all the shortcomings of Ghana’s psychiatric system. J. B. Asare, the country’s former chief psychiatrist, described the discarded project to me as just one of a “series of unrealized dreams.” Any prospect of improvement was thwarted by an ensemble of political and economic woes. In the Seventies and Eighties, while Europe and North America were being flooded with new drug therapies and shuttering their psychiatric hospitals in the name of community mental health, Ghana suffered three military coups and several financial crises. Medical professionals left the country in droves. Under austerity constraints imposed by the World Bank and other foreign creditors, Ghana’s government had neither the will nor the capacity to invest in a public psychiatric system.

Twenty-five-year-old Odeneho Samson, restrained by the leg at Nazareth, being prayed over to remove the spirits believed to be causing his mental illness

By the time Samuel and Philomena fell sick, the country’s circumstances, as in much of West Africa, were manifestly grim. A mere 2 percent of Ghanaians with serious mental health needs had access to treatment of any sort; the relative few who were hospitalized were routinely subjected to involuntary injections, electroconvulsive therapy without anesthesia, and overcrowded, unsupervised wards. Not for nothing were Ghana’s government-run asylums popularly perceived as places where you went to die.

In the 1990s, as the new Pentecostal churches sought to fill the vacuum left by the state’s retreat from providing social services, the prayer camps began proliferating. Drawn by reports of sensational miracles, supplicants flocked to the mountains and forests in the south, where most of the camps were located. Some grew into enormous settlements as big as towns; others were ramshackle operations with little more than a signboard and a plot of land. (Healing therapies were also offered by traditional shrines and, in the north, a handful of mosques.) The pastors and healers, prophets and prophetesses running the camps typically lived on site, where they were sustained by tithes, offerings, and consultation fees (and sometimes by farming and business initiatives). Several had close ties to major Pentecostal churches and denominations. Others refused to accede to any authority, or “anointing,” but their own. Those visiting the camps were equally diverse, in terms of both the predicaments that brought them there — disease, financial problems, difficulty getting pregnant — and their class and social backgrounds. At the larger, more established camps it was common for the poorest of the poor to find themselves praying and fasting alongside Ghana’s political and business elite.

Soon numbering in the hundreds, these secluded healing centers evolved to be as heterogeneous as the Pentecostal movement itself. But they shared a few basic convictions. First, that God had promised his people not just life but life “abundant,” as it says in the Book of John. And second, that sickness and misfortune were the result of one’s true reality having been blocked or thwarted — by the Enemy and his agents, by human foes, by one’s own transgressions. Whatever the circumstances, the camps were there to identify such threats and help eliminate them.

When Martin arrived at Nazareth Prayer Centre with his mother and siblings, he was shocked by the dingy, primitive appearance of the place, and also by its size: an unending series of run-down buildings, constructed in the traditional mud-and-thatch style, separated by a maze of muddy pathways. The family fell into a routine organized around twice-daily prayer services, revival meetings, extended healing and deliverance sessions, weekly Bible study, and consultations with Prophet Tawiah, the camp’s founder. Martin went to school as Agnes looked after her two young daughters, Veronica and Dorcas, and ensured that Samuel and Philomena stayed safe. (Her eldest son was attending secondary school and had remained behind with Anthony.) Several months passed. By the end of their first year at the camp, their resources had dwindled, and Agnes was struggling to feed the six of them. Martin dropped out of school and began working on a local cassava farm. Anthony was becoming less and less a presence in their lives, and his support, financial and otherwise, grew scarce. “Now and then he came around on the weekend,” Martin said. “If he had money in his pocket — thirty cedis, forty cedis — maybe he would give it to my mom.” Beyond that, they were on their own.

Philomena seemed to benefit from the camp’s structured, communal environment, but Samuel’s symptoms steadily intensified. One afternoon, Agnes was preparing a large cauldron of soup on an open fire, and Samuel ran over and shoved it violently. As Agnes and a neighbor scrambled to contain the flames, Samuel hurled stones at them. Agnes screamed for help. The pastor who arrived demanded a severe but not unusual measure: that Samuel be shackled to a tree outside the family’s room. The pastor explained that, lacking more sophisticated methods of restraint (injections, locked isolation rooms, padded leg or arm cuffs), this was the only sure way to protect both Samuel and the other residents as they waited for God to heal him. It was not a form of discipline, Martin told me. It was an act of desperation. What if Samuel ran off into the forest? Or killed somebody, or himself?

The sight of his younger brother chained was almost too much for Martin to bear. Whenever Prophet Tawiah came to pray for him, Samuel writhed and struggled, begging to be released. Sometimes they did free him, but inevitably he would be chained again. Many nights, especially during thunderstorms, Agnes left her bedroom to lie beside Samuel on his mattress under the tree. Martin could hear her singing to him, trying to calm him, intoning the same psalms she used to pray over him in his bed back home.

The Donkohs were not alone in their hardship. The camp housed a number of families who had arrived at Nazareth after years of shuttling from one clinic, hospital, or church to another. They’d done everything they were told to do, gone everywhere they were told to go. Some had incorporated medicine, such as they could, into the otherwise spiritual treatments they’d received; a number of them had traveled as far as Togo or Nigeria to seek healing. Yet here they were. While wealthy Ghanaians had at their disposal private residential facilities and rehabilitation centers, behavioral therapies and imported drugs, those at Nazareth had none of these. Most were extremely poor, their expenses offset by the donations of more affluent parishioners. The exhaustion, the destitution, the shame at a situation in which having your son or daughter shackled could come as a relief — Agnes recognized all of it in her fellow caregivers. But perhaps their most significant shared experience was the one hardest for them to talk about: the rejection they had undergone at the hands of neighbors, former friends, co-workers, church leaders, even immediate kin.

In Ghana, and throughout sub-Saharan Africa, the stigma of mental illness is profound. Once branded, individuals and their family members — as well as, in some instances, the nurses or hospital staff who care for them — can find it impossible to secure employment, housing, or a spouse. In fact, before many Ghanaian households will agree to a potential marriage, they will investigate the suitor’s background to make sure that there are no rumors of madness among his relations. Nazareth offered a shelter from this discrimination. Amid the hundreds of pilgrims who had arrived for some other reason, who could come and go as they pleased and whose circumstances, however dire, did not make them pariahs, there existed a fragile, largely hidden enclave — a community for those who had no community.

But as a refuge it had its limits. On an unusually hot day in the middle of the dry season, Agnes was walking home after a morning service when a group of kids told her that her daughter was being attacked. With Veronica and Dorcas trailing behind her, Agnes arrived outside the modest home of a middle-aged pastor and his wife, for whom Philomena worked doing small chores. She found Philomena, stunned and bleeding, cowering in the dirt as the pastor’s wife hurled slurs — mad girl, lunatic. Philomena had been caught trying on her employer’s jewelry; claiming that the earrings and necklaces belonged to her, she refused to take them off.

In the following days, Philomena’s more florid symptoms reappeared, and she was chained to a tree stump just out of reach of her brother. She remained shackled for several months, until late 2004, when Prophet Tawiah sat Agnes down to talk. “He told her it would be better for us to go somewhere else,” Martin recalled. “Samuel and Philomena were still in bad shape. He said there was nothing else he could do for us.”

The family wandered first to one prayer camp, then another, and then another and another: nine camps over the following twelve years. They sought assistance at hospitals, they received medications and two diagnoses of schizophrenia, and Agnes’s oldest son, now a primary-school teacher, sometimes sent money, but a vicious circle of poverty, unstable housing, and chronic sickness made lasting relief elusive. In 2007, Anthony died, the result of a liver disease. In 2011, Agnes’s youngest daughter, Veronica, experienced her first psychotic episode; eventually she, too, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Then Philomena’s health began to deteriorate. She had developed diabetes — a metabolic effect of the antipsychotic drugs she’d been taking on and off since leaving Nazareth — and, in February 2012, unable to maintain her insulin regimen and a proper diet, she started showing signs of diabetic ketoacidosis. One night, Martin and Agnes were awoken by the sound of Philomena vomiting and gasping for air. They rushed her to a local clinic, but she stopped breathing before they got there. She was thirty-three.

“If you remember, in the Bible,” Martin reflected, “there was a short way to the Promised Land. But God took his people through the desert. And during the journey, a lot of them perished — most of them suffered.” Still the Israelites persisted. “That’s what we had to do,” Martin said. “We had to keep moving.”

In July 2016, I accompanied Stephen Asante, a thoughtful, soft-spoken psychiatric nurse, on a trip to Edumfa Heavenly Ministry Spiritual Revival and Healing Centre, where the Donkohs were now living. Born and raised in southern Ghana, the twenty-nine-year-old Pentecostal had been stationed for the past couple of years at an outpatient clinic in the predominantly Muslim north. Asante believed, like many of his colleagues, that it was the widespread illiteracy, or magical thinking, or just plain superstition of the citizenry that had caused places like Edumfa to multiply over the past two decades. As he saw it, the crisis of mental health stemmed from the fact that so many would-be patients were seeking treatment at these dangerously unregulated establishments. The camps could be rendered superfluous, he was convinced, if only people would comprehend the true — that is to say, the biological — nature of mental illness. Lately, he’d been asking God to expand his work beyond the confines of the clinic, and he sensed that he was being led to this particular place for a reason.

A patient in the restraint home at Edumfa, where those considered violent or at risk of running away are caged

It was raining as our taxi passed under an arch with the heavenly ministry etched in peeling block letters across the top. Covering dozens of acres of dense tropical forest near the popular tourist beaches of Cape Coast, Edumfa — one of the biggest prayer camps in West Africa — was a vast expanse of low cinder-block buildings and kiosks and neat dirt roads that could have been mistaken for an army barracks were it not for the gold-painted pillars and the garish murals of a white, bearded, long-haired Jesus: Jesus performing miracles, Jesus ascending to Heaven, Jesus addressing his disciples. Residents clutched plastic bottles filled with a dark reddish liquid — water mixed with the powdered bark of the Tree of God, an enormous Alstonia on the property that was said to have curative powers.

Beyond a guarded gate stood the office of Apostle Emmanuel Blessed Bedford, who ran the camp with his wife, Prophetess Rebekah Nhyirah Bedford. The circular, glass-walled office was an ostentatious take on the traditional Ghanaian summer hut, furnished with a broad wooden desk, a computer, two white leather couches, and, in the center, an ornate thronelike chair on which sat the apostle, a heavyset man with short hair and a trimmed gray beard. When we came in, he glanced up from a pile of papers on his lap and, without saying a word, nodded to the couch. At the computer, a teenager was entering a huge stack of prayer requests into a database; to his right, on the other couch, an older man in an ill-fitting suit thumbed through the Oxford Picture Dictionary.

Fifteen soundless minutes passed. Suddenly, an instrumental flute version of “Amazing Grace” issued from the apostle’s iPhone. “Yes?” he answered on speaker. Into the room exploded a female voice, screeching and making guttural noises. “The woman has a demon,” Asante whispered to me. The apostle brought the phone to his ear and conducted the rest of the call privately. We could hear him speaking in tongues. When he hung up, he went on ignoring us.

The cool reception was to be expected. In October 2012, Human Rights Watch had released a scathing exposé, Like a Death Sentence, in which Edumfa and a handful of other prayer camps were singled out for their methods of treating the mentally ill. Likening the camps to prisons for the disabled, news outlets ran lurid summaries of the report, culminating in a 2013 inquiry by Juan Méndez, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture, who denounced the conditions at these facilities as degrading and inhumane.

Ghana’s politicians and business leaders were shocked, not so much at the harrowing content of the investigations — many of them, after all, had frequented the camps themselves — as at the negative press their country was receiving. Since the early 2000s, Ghana had managed to transform itself into an African success story, a beacon of stability in a region rent by dysfunction. President Obama made it his first official trip to sub-Saharan Africa, in 2009, and U2’s Bono summed up the general view of the country in a New York Times op-ed: “Quietly, modestly — but also heroically — Ghana’s going about the business of rebranding a continent.” In short, this was a nation more accustomed to partnering with the U.N. than to being reprimanded by it. Not surprisingly, then, the persistent demands that Ghana’s government crack down on the camps — and, if need be, criminalize and shutter them — began having an effect. Today there is talk of tribunals and other legal measures.

When at last the apostle turned to us, he said that he had become suspicious of outsiders visiting. So many lies, he said. Now they’re trying to shut us down. The humanitarian groups were less concerned with the well-being of the people than with pushing their own agenda. He didn’t elaborate on what that was, but he did say that recently, a British woman in a wheelchair had come to Edumfa with a film crew. Granted access, the woman and her companions proceeded to the restraint home — the building where some of the “mentally disturbed” residents were housed. It turned out that the group was with the BBC. Their story, “The Country Where Disabled People Are Beaten and Chained,” appeared online a few months later.

In the end, whether because he believed us when we said we had no intention of deceiving them or because he felt there was nothing left for us to uncover, he gave us permission to stay.

The yard outside the restraint home, where Veronica and Samuel resided, looked no different from any other part of the camp, except for a set of empty chains and leg irons fastened to a nearby tree. Like the rest of the derelict building, the wooden threshold of the men’s quarters (the women resided in a separate room) was low and rickety, and we had to be careful not to hit our heads as we stepped inside. Then two sensations, intertwined: a sweaty, sooty darkness, and the smell — feces and urine and rot. And voices, lots of them. “Obruni, how are you?” A row of cages, each one maybe four feet wide by six feet deep by five and a half feet tall, stretched from one end of the room to the other, separated by floor-to-ceiling concrete dividers. Every cage held a man or a child, some partially clothed, others completely naked. Mosquitoes swarmed; a line of red soldier ants advanced up the blistered, scabbing leg of a young man splayed out on the floor. Asante tried, largely without success, to engage those awake in the kind of interview he might conduct with a patient at his clinic. Some appeared to be in the grip of unmedicated psychosis; others, he learned later, suffered from untreated epilepsy or had developmental disabilities. It wasn’t long before Asante, dazed and overcome, excused himself.

Outside, the building’s caretaker, a rail-thin man wearing baggy trousers, flip-flops, and a sweat-stained undershirt, explained that he had once been a resident, and had volunteered to stay on when — as he put it — his healing came. He was going into his seventeenth year at Edumfa.

“I know it’s terrible, really terrible,” he said. “We should be giving them a better environment. The relatives do their best to make it comfortable, but they don’t have the resources.” He described how various journalists and delegations had visited the restraint home, taking notes, conducting interviews, snapping pictures. And every one of them left “without giving us so much as a mattress or a bag of rice, not even a single cedi to make things better here.”

“That room,” he continued, “is not a punishment. What are we supposed to do?” He lifted his shirt to reveal a collection of fresh bruises on his torso, accumulated while trying to prevent a young man from running away. “Do you think we like the cages? If the human rights people want something else, they should come and build it for us.”

Dusk was falling, and residents were setting off toward Jericho — an immense, unfinished structure towering above the forest on the outer reaches of the camp. Originally intended as a grand cathedral, the skeletal edifice had been repurposed as a site of pilgrimage. Each day at sunup and sundown, everyone who was able marched around the concrete complex seven times, commanding the walls in their lives to come tumbling down. Some blew horns or trumpets or banged on hand drums or tambourines; some carried cutlasses or machetes, swiping at their spiritual enemies as they walked. The ritual was vital for the families of those confined. It’s when their prayers, they believed, were at their most potent, most efficacious pitch — when God was most likely to hear their cries.

In March 2012, Ghana’s parliament passed an ambitious piece of legislation intended to overhaul the country’s mental health system. Vigorously championed by the World Health Organization and other advocacy groups, the Mental Health Act promised to deliver, in the words of one British consultant, “high-quality, accessible, affordable, and sustainable mental health care,” with a strong emphasis on patients’ rights and on moving away from an institution-based model of treatment. For more than a century, those struggling with mental disorders had often been left to their own devices; in many instances, they had been rounded up and forgotten about. No longer would that be the case. “It is my expectation,” the director of Accra Psychiatric Hospital gushed on the day of the bill’s passage, “that five years from now there will be no mad persons roaming the streets of the country, since they will be effectively treated and integrated into society.”

There was only one problem. The Mental Health Act was not backed by a legislative instrument detailing how its protocols would be put into effect, or — most crucially — how its initiatives would be financed. Peter Yaro, the executive director of BasicNeeds Ghana, the nation’s leading mental health advocacy organization, chuckled darkly when I asked him to explain this gulf between rhetoric and action. “In Ghana, we are good at making laws,” he said. “Unfortunately, we are poor at implementing them.”

Five years and counting after the bill’s adoption, the quality of mental health care in the country, by every available measure, has actually declined. A 2016 study conducted using the W.H.O.’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems presents a bleak picture of the situation. With a dearth not only of basic medicines but also of trained providers (there are a mere sixteen psychiatrists nationwide to treat an estimated 2.7 million people with mental and substance-use disorders), this is a country whose treatment gap has, if anything, widened in the period since the Donkoh children first fell sick. Medications are unavailable — and even when they can be found, patients and their relatives, obliged to pay out of pocket at overpriced pharmacies, must often forgo them anyway. Public hospitals, which supposedly offer treatment to all, are able to care only for those who can pay. And local primary-care providers, the linchpin of any effort to reach those in rural areas, are reluctant to offer services related to mental health, since the National Health Insurance Authority has been unwilling to reimburse them.

But the most striking evidence of Ghana’s predicament has come from Accra Psychiatric Hospital, the country’s flagship institution. When I visited in August, an uneasy quiet hung over its deserted yards and barely half-full wards. An administrator told me that the Ministry of Health had forsaken its fiscal responsibilities to the hospital, and now it owed nearly $1 million to its suppliers — who were halting the delivery of everything from bedsheets to bandages and toilet paper. Admissions had been discontinued, and many of the hospital’s five-hundred-plus occupants were reportedly discharged en masse. (Officials later denied these accounts.) The nurses were incensed that it was precisely the most at-risk people who were being sent away. “These patients needed help,” said Sandra, a veteran nurse in the female ward, pointing to a row of empty beds. “A lot of these people, they were here because nobody wanted them.”

By late October, the hospital’s employees had gone on strike, and even its outpatient operations were suspended. Those patients who remained faced a shortage of food and medicine. As word leaked out, some commentators seized on the story as a prime example of government negligence under President John Mahama, who was up for reelection in December; during his tenure, he had overseen such state-financed ventures as the building of West Africa’s largest luxury mall, with the reported price tag of $93 million, while claiming a lack of funds for public services like health care and electricity. (The administration of President Nana Akufo-Addo, who replaced Mahama in January, has said little about mental health since taking office.)

To be sure, such problems are by no means unique to Ghana. Nor is this “failure of humanity,” as the Harvard psychiatrist Arthur Kleinman has referred to it, exclusive to the so-called developing world. Peter Yaro of BasicNeeds remarked that turning a blind eye to the most vulnerable and marginalized members of society is a habit common to policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic. And donor agencies like USAID, he added, strongly influence Ghana’s actions. “Believe me,” Yaro said, “if mental health were a priority for your country, it would become a priority here in Ghana.”

One could argue, in fact, that Ghana is simply following the lead of Europe and the United States where the abandonment, or worse, of its mentally ill population is concerned. When President Kennedy ushered in the process known as deinstitutionalization with the signing of his Community Mental Health Act, in 1963, it was with the aim of emptying out the asylums and state hospitals in favor of community care. Writing in this magazine in 1975, the author and physician Mark Vonnegut was already offering an autopsy of this “lovely vision” that never became more than that.

Four decades later, prisons and jails are America’s de facto mental health facilities, warehousing, often in solitary confinement, upwards of 383,000 men and women with severe and chronic mental disorders — or more than ten times the number of patients in all of the country’s psychiatric hospitals combined. And then there’s the estimated 169,000 homeless individuals with mental illness, and those living in for-profit residential centers and nursing homes. “Here, ecologically separated and isolated from the rest of us,” the sociologist Andrew Scull observes in Madness in Civilization, “the most useless and unwanted segments of our society can be left to decompose, quietly, and, save for the occasional media exposé, all but invisibly.”

When Asante and I headed down to the restraint home to meet with Agnes and her children, we found her preparing breakfast and tidying up the grounds along with the other relatives. Some of the men and women who had been confined yesterday were now scattered throughout the courtyard, eating or huddled with their family members.

Veronica was perched alone on a low brick wall, her knees pulled up underneath her chin, a threadbare white nightgown covering her legs and feet. She showed no awareness of our presence when we went to greet her. Agnes, who never seemed to stop looking in Veronica’s direction, smiled and shrugged. As she and Martin arranged a semicircle of plastic chairs, Samuel hovered behind them, trying to help. He was beaming and affable, but efforts to elicit conversation were futile. When Asante asked him a series of gentle questions (“Have you eaten today?” “Do you know where you are?”) he repeated the words back verbatim, or offered otherwise opaque replies. He and Veronica, as well as a couple of other patients, had a pale dustlike substance covering their scalps: powdered bark from the Tree of God. We took our seats. “You are welcome,” Agnes said in the customary manner of a hostess inviting visitors into her home.

Asante asked whether her children had ever been seen at a hospital. The answer, he assumed, was no. Agnes said a few words in Twi and shuffled into a nearby building. “She wants to fetch something from her room,” Martin explained. When she returned, she was clutching a pair of bulging, time-worn manila folders. It was the aggregate mass of her children’s dealings with Ghana’s health system.

As Martin began recounting the family’s saga, Asante pored over the documents, only half listening. Then he cut in, uncharacteristically upset. “Please, can you tell me if Veronica has had any trouble with medications?” He held a note from a hospital visit in Kumasi two years earlier. It was written by a psychiatric nurse. “Reported with mother, complains of being aggressive both verbally and physically. Insomnia. Destructive. Talks to self. Picks waste items from floor.” Under plan, it read: “Educate on condition and importance of adhering to treatment.” It was this last part that shocked Asante. The nurse had ordered a dangerous dosage of three antipsychotic drugs (chlorpromazine, modecate, and haloperidol) to be taken in concert, a combination that could result in terrible side effects.

The document shed light on a painful mystery. After Veronica started taking the pills, she began suffering violent seizures. Agnes, who regretted having pressured Philomena to take the medications that she believed ultimately killed her, saw the terrifying convulsions as a warning. By the time we met at Edumfa, she was no longer giving Veronica the drugs, saving them for Samuel instead. (He tended to respond better to medication.) The problem, Asante realized, was not that Agnes had failed to follow the treatment plan. The problem was that she had adhered to it. Agnes’s decision was understandable. Better to see Veronica in a cage than to see her dead.

Before the camp’s evening service, Asante took some time alone to pray and write. The situation with Veronica and Samuel — the overdosage, the seizures, the restraint home, the seeming intractability of it all — was weighing heavily on him. His discovery of the flawed prescription had shaken his confidence in the system to which he’d dedicated his life.

Akwasi Osei, Ghana’s leading psychiatrist and the chief executive of the government’s Mental Health Authority, had no such qualms when I met with him at the M.H.A.’s plush headquarters in Accra the following week. Osei replied with a single word to the question of why so many families turned to the prayer camps: “ignorance.” The solution, he said, was straightforward: “Our people need to be educated about mental health.” Like other public health emergencies in West Africa (the recent Ebola outbreak being the most dramatic example), Ghana’s mental health crisis, in this view, was a product less of neglect or misguided policy than of primitive epistemology.

Asante no longer shared this perspective. He was convinced that the antipsychotics themselves were not to blame, and that a proper treatment plan, if diligently overseen, would allow Veronica to get better. Yet he was also cognizant of a hunger for answers that, in some cases, even the most sophisticated medicine could not provide. The Donkohs’ plight had taken him back to his own past. As an adolescent, he had witnessed his father die of alcoholism. The years before his death had been filled with trips to numerous prophets and healers, all-night prayer meetings and exorcisms, as Asante and his mother and older sister — and his father, too — held to the conviction that freedom from the disease lay just over the horizon. They knew, he told me, that it was a chemical dependence. But why did it afflict his father in particular? Other fathers drank, but only his had become a slave to it. Even with his training and medical proficiency, Asante was certain that there was a “spiritual aspect” that needed to be addressed but wasn’t; he was also confident that his father would still be alive if he’d had access to cognitive behavioral therapy and antidepressants. In the same way, he could see that Agnes had accepted that what beleaguered her children was in fact a medical disorder. But this knowledge hardly helped in extracting meaning from it.

If all maladies are difficult to make sense of, mental illness, particularly schizophrenia and psychosis, may be especially inscrutable. It had been hard over the years for Asante to hear his mentor, the sole psychiatrist in the northern part of the country, tell countless men and women that they would likely bear their burden for the rest of their lives. A self-described freethinker with little patience for unfounded hope, Mohammed Soori (who passed away in October 2016) felt it his duty to convey the harsh truth of chronicity to those in his care. Severe psychiatric disorders were not sicknesses just like any other — nor, in most cases, could they be cured. They were infirmities that, at best, could only be managed. The medications he gave his patients would merely alleviate their symptoms; they wouldn’t heal the underlying disorder.

“Honestly, it’s a very hard life,” Timothy Debrah, the head nurse at Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital, just outside Cape Coast, told me. “We’re always pleading with them to stay away from the camps. But can we fault them for going?”

It’s with this question in mind that some experts have begun advocating a rapprochement between the prayer camps and Ghana’s formal health system. A recent article coauthored by a group of scholars from Yale, Harvard, and the University of Ghana noted that nearly all the pastors and prophets they interviewed were amenable to the idea of partnering with biomedical-care providers, and open to modifying even their most fundamental practices to accommodate treatment (for example, allowing a family member to fast on the patient’s behalf while he or she was on medication). These calls for collaboration are premised on the argument that existing sociocultural realities — family support structures, religious sensibilities, lay conceptions of illness and recovery — should be integrated into the provision of psychiatric care. They stem also from a recognition that the prayer camps will be a fixture in Ghana for some time to come. A 2016 report sponsored by the U.K.’s Department for International Development found that the sixty-five “faith-based facilities” it surveyed were together accommodating 9,150 people with mental illness. Multiply this by the number of camps operating in Ghana and neighboring nations, and the figure is staggering.

As Asante saw it, the promise of community mental health — the explicit aim of Ghana’s Mental Health Act — would go unfulfilled so long as the country’s psychiatric establishment remained unwilling to engage with communities such as prayer camps. Partnering with the camps, he suggested, could take a variety of forms, running the gamut of medical and psychosocial services: administering medications and closely monitoring adverse side effects, such as those experienced by Veronica and Philomena; helping to calm episodes of acute aggression or agitation; seeking assistance from outside institutions (NGOs, universities, churches, government agencies); or working with camp leaders to ensure restraints were used sparingly and with a minimum of discomfort. “We could be doing so much more,” Asante told me. “Really, it’s not complicated.”

But of course it is complicated. If medical engagement with the camps is to extend beyond its current sporadic, cursory, severely underfunded form, it will require broad support from both international aid organizations and Ghana’s Ministry of Health, in particular the Mental Health Authority. Such support, however, does not appear to be forthcoming. When I spoke with Osei at the M.H.A. office, he acknowledged that collaboration with the camps was important, but in the end he seemed more preoccupied with reeducating, and, if necessary, censuring their leaders. In part this had to do with an ideological resistance to permitting religion (“faulty belief systems,” as Osei referred to them) to impinge on the rightful jurisdiction of biomedicine; in part it had to do with entrenched views of what the proper delivery of mental health care ought to entail. As the anthropologist Ursula Read points out in the journal Transcultural Psychiatry,

The idea that Africa might develop its own models of health care, rather than pale imitations of those in [Western] countries, seems to have fallen out of favor in the drive for standardization.

Yet there’s another, simpler explanation for this absence of engagement with the camps: it would look bad. In the well-intentioned but bizarre reasoning of powerful organizations such as Human Rights Watch, associating — much less collaborating — with the prayer camps would be tantamount to endorsing them. You don’t partner with purveyors of torture and “inhumanity,” they’ve made clear to the Ghanaian government. You expose, denounce, and, if necessary, punish them — even if this means, as with the visiting delegations of humanitarian observers, leaving those languishing in the camps in exactly the state you found them.

The dilemma haunts Peter Yaro and other local advocates, many of whom have spent their careers trying to improve the lot of the mentally disabled and their caregivers. When I asked Yaro why BasicNeeds — which has a direct line to the Ministry of Health and is funded by European and American donors — hadn’t done more to offer assistance to families residing in camps like Edumfa and Nazareth, he was quiet for a moment. “I would like to make things better for them,” he finally said. “I really would. We could easily drill a hole for water, or bring in supplies and medicine. But we can’t. It would be like we were giving these places our stamp of approval.”

Toward the end of my stay in Ghana, I received a call from Martin. In the background, I could hear the amplified din of worship music emanating from an auditorium near the Edumfa restraint home. We spoke about what the immediate future might hold for his family. In 2007, after his father passed away, Martin had applied for a scholarship from an NGO, Plan International, which allowed him to resume his education. Now he was in his final year of nursing school at the University of Cape Coast, not far from the camp. He found it challenging to keep up with the coursework. Reluctant to leave the prayer camp for more than a few hours at a time, he spent most days assisting his mother, and often felt too depleted to study. He was intent, however, on finishing his degree. His hope was to become a psychiatric nurse.

As promised, Asante had visited them again before returning to the north. He’d started Samuel and Veronica on a new drug regimen, and he assured the family that before long they would see improvement. Soon, Asante said, the cages would be unnecessary.

Still, much remained frightening and uncertain. Martin worried that the home his mother longed for, that she so deserved, might never materialize. He was scared that Samuel and Veronica might never recover, that Philomena’s fate could be theirs as well. That he might someday fall sick himself. That the stigma of mental illness would prevent him from marrying or having children. For solace, he turned to a verse in Ecclesiastes, given to him by a pastor when he was young. “I try to remember,” Martin said, paraphrasing the scripture, “that God can make all things beautiful in his time.”

Before saying goodbye, Martin added that earlier, for the first time, his brother and sister had accompanied him on his nightly trek around Jericho. He’d needed to hold their hands, and in the dark they had to move very carefully. But they persisted. Seven times they circled the walls together, the sound of the prayers and trumpets rising into the sky.