On a sweltering day in August 2012, Ana Duran heard dogs barking in the distance. For two days, she and several other migrants had been wandering, thirsty and disoriented, through grassland and spindly mesquite trees in southern Arizona. Now they could see four federal agents running toward them.

Duran, a petite woman in her early thirties, with soft, rounded features and strawberry-blond hair, had fled Guatemala to escape her abusive husband, from whom she had separated two years earlier. Duran had recently sought a formal protective order against him, but he still came to her house, in an industrial suburb of the capital, often under the guise of seeing their sons, aged seven, eight, and fifteen. He would tackle her to the ground, kick her, and punch her in the head. Sometimes he would rape her. That spring, he had slashed a knife across the left side of her chest and threatened to cut her heart out.

In May, her husband had loosened the lug nuts on her car, causing it to veer out of control while her sons were in the back seat. When he was driving, he would sometimes accelerate wildly, proclaiming that it might be a good idea to smash into a wall and “end the party.” (To protect Duran’s family in Guatemala, her name has been changed.)

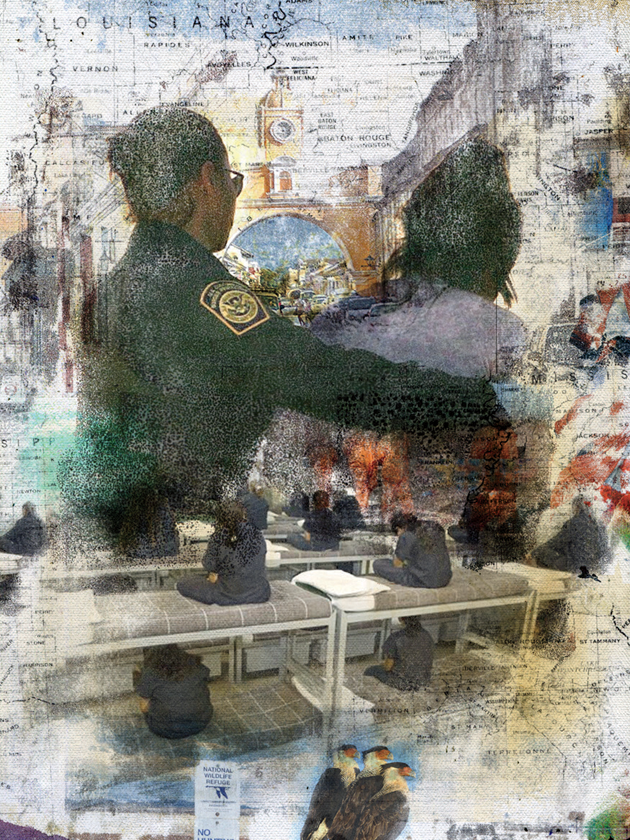

Collages by Brian Hubble. Source photographs: Eric and Jessica Alva © Guillermo Contreras/San Antonio Express-News/ZUMA Wire

Law enforcement hadn’t intervened, perhaps in part because Duran’s husband had friends on the police force. He worked as an administrator at a nearby high school and, according to Duran, routinely falsified diplomas to help aspiring officers enter the training corps. “The police don’t come when you call them,” she said. “They come after the person’s already dead.”

Terrified for her own safety, Duran began to feel that her presence posed a danger to her children too. Her sister, her neighbors, even her mother-in-law urged her to leave the country.

Duran decided to pose as a tourist traveling through Mexico and then cross over to the United States. Before she left, she went to a salon for a haircut and a manicure, and packed light, just a few changes of clothes in a small suitcase, so as not to arouse suspicion from Mexican authorities. She took her children to stay with relatives, telling herself she would need only to reach America and make a little bit of money, and then she could send for them.

The journey through Guatemala and Mexico had been arduous, and when Duran saw the agents approaching, she was relieved. She told them that she feared for her life and needed protection. The agents took Duran to a detention facility in Eloy, Arizona. After a few months, she was loaded onto an airplane and transferred to the LaSalle Detention Center, which sits on ten acres of cleared pine forest in central Louisiana. She remembers riding up a wide concrete driveway toward an arched facade framed by swirls of concertina wire. “It was something ugly,” she told me later.

Despite the bleak surroundings, Duran was hopeful. Her life in Guatemala had been a chronicle of trust betrayed. The husband who beat her, the state that failed to protect her. She knew little about America, but expected for the first time in a long while to get the fair shake she deserved. Before leaving Guatemala, Duran had asked her pastor to write a letter attesting to her character, which she planned to show to a judge. He described her as someone who had suffered tremendously yet had always been a fighter. Now her fighting days seemed finally to be over.

But Duran soon found that she had exchanged one form of confinement for another. At LaSalle, she had trouble sleeping; she dreamed constantly of her husband trying to kill her. A psychologist at the medical center diagnosed her with adjustment disorder and depression. Unable to afford the fees charged by the private company that operated the telephones, Duran couldn’t even call her children. After five months in the United States, she had no idea when she would be let out, much less whether she’d be allowed to remain in the country.

LaSalle is part of America’s vast immigrant detention network, the largest in the world. Over the past decade, this system has held an average of 400,000 people each year. Since 2009, Congress has required the Department of Homeland Security to provide at least 33,400 beds for immigrant detainees on any given day. (In 2010, the quota was bumped up to 34,000, and last summer, Thomas Homan, the acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, announced his intention to expand daily capacity to more than 50,000.)

Since deportation is a civil procedure and not a matter of criminal law, immigrants facing removal from the country have no right to legal counsel. Duran knew she needed help. According to the American Immigration Council, having an attorney makes it ten times more likely that a detained immigrant will win her case, but the representation rate hovers at just 14 percent. Duran’s prospects were worse still. Between 2007 and 2012, judges at the Oakdale Immigration Court, where she would appear, heard 42,521 cases—the majority of Louisiana’s immigration docket—and ordered nine out of ten people deported. A mere 6 percent of detained immigrants had a lawyer by their side.

One day, Duran overheard a group of women speaking rapturously about someone they called Abogada Jessica, who paid frequent visits to the detention center despite its remote location. (Abogada means “lawyer” in Spanish.) This was unusual. Representatives from Catholic Charities in Baton Rouge sometimes made the two-and-a-half-hour drive to LaSalle to hold information sessions about deportation and asylum, but the organization didn’t have the resources to represent more than a few dozen people each year. Visits from private attorneys were virtually nonexistent. Abogada Jessica’s reputation had reached such mythic proportions that she became known simply as La Famosa. She was said to have deep connections with guards and immigration judges. Detainees whispered that Jessica herself was the daughter of an undocumented immigrant, that she lent a sympathetic ear in an otherwise impenetrable bureaucracy. She assured detainees that she would have them out of LaSalle within a month, that she’d even get them work permits. She had thick black hair and impeccable makeup, and she always wore high heels. Duran imagined her as a character from a telenovela. The women at LaSalle told Duran that in order to secure a consultation with Abogada Jessica, she needed to write down her name and Alien Registration Number on a slip of paper, which would be passed on by a current client. If Jessica decided to take the case, she would summon Duran during her next visit.

A week or two later, in January 2013, Duran was called to meet with Jessica, who saw clients in a small room that also held weekly church services. It was hard to say who was more popular: the preacher or La Famosa. On the evening in question, the room was packed with detainees, women in blue jumpsuits and government-issue slippers seated on metal folding chairs, awaiting their turn to speak to the lawyer with the silver tongue. Jessica stood at the front. She raised her hands and spoke in a voice that was high and rhythmic, vowels squeezed by her lilting Texas twang. My friends, my friends, I’m so happy you’re here. I come bearing good news.

Duran had been longing for this moment, when she would finally be able to share her story with someone who could help. She had tried to assemble the details of her abuse into a coherent narrative. She knew it was important to have as much information as possible to convince a judge that she qualified for asylum.

Currently, the US government has five narrow categories under which individuals are eligible for asylum: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, and membership in a particular social group. For years, lawyers had argued that victims of domestic violence constituted a “particular social group” deserving asylum, but rulings were inconsistent until 2014, when the Board of Immigration Appeals established a clear precedent, finding in favor of another Guatemalan mother of three. Human rights organizations have extensively documented the prevalence of domestic abuse in Guatemala. A report from the United Nations’ special rapporteur on violence against women estimated, conservatively, that 36 percent of Guatemalan women who live with a male partner suffer domestic abuse. The country has one of the highest rates of femicide in the world.

That evening at LaSalle, Duran expected to have a meaningful conversation about her asylum claim. But Jessica focused instead on more transactional details. “For her, nothing was complicated,” Duran said. “She told me everything was going to be fine, that I just had to get my brother to deposit a thousand dollars for her to get started on my case.”

When Duran returned to the dormitory that night, she was elated. Several months would pass before she learned the truth, that Jessica was not an attorney at all. That she didn’t even have a bachelor’s degree. That many of her current clients, who Duran thought were being released on bond, were actually being deported. Jessica called Duran’s brother in Maryland and persuaded him to pay the money, and then Duran never saw or heard from Jessica again.

Undocumented immigrants have long been targeted by swindlers who promise shortcuts through the labyrinthine corridors of immigration law. What happened to Duran is most commonly called notario fraud, a catchall term that refers to a scam in which an individual misrepresents his or her qualifications to handle immigration work. The English word “notary” is a false cognate for the Spanish notario; in many Latin American countries, a notario público is a licensed attorney, whereas in the United States a notary is only a witness to the signature of forms. Scammers deliberately exploit the confusion.

Not only do notario fraudsters charge unwitting victims for bogus services, they sometimes make them pay for documents that should be provided for free. Those documents, filed incorrectly or not at all, can irreversibly damage an immigration case. In an overburdened system that offers few second chances, false claims and missed deadlines can lead to deportation. By the time clients realize what has happened, often months or years later, the notario has disappeared. “It’s like a sickness,” said Ramon Curiel, an immigration attorney in San Antonio. “You have an underrepresented and underinformed constituency in a system that’s very easy to manipulate, at least temporarily. If you add some greed and just a little bit of knowledge, you can do a lot of harm.”

Because of fears about their legal status, immigrants are reluctant to report such crimes to the police. It comes as no surprise, then, that experts struggle to measure the extent of notario and other forms of legal fraud. Since Duran met Jessica at the beginning of 2013, the Federal Trade Commission has logged nearly 5,500 reports of immigration services fraud. But the FTC’s figure almost certainly represents only a tiny percentage of the total. Anne Schaufele, a former attorney at Ayuda, an immigrant services nonprofit in Washington, estimates that one out of every ten immigrants who walks through the agency’s doors has been the victim of some type of notario fraud. Schaufele has worked with immigrants who have lost as little as $60 or as much as $60,000. On a national scale, those numbers add up. “It’s tens of millions of dollars per year,” she told me. “Probably more.”

The physical isolation of detention centers creates a distance between lawyers and their clients that can be exploited. Attorneys often send staff members, called runners, to shuttle documents to and from officials and conduct interviews with clients. As Jessica later admitted during a deposition, “people can take advantage.” The runners are the first, and sometimes only, line of communication between lawyers and detainees. Schaufele calls Jessica’s type of scheme, in which runners scam detainees by using the credentials of absentee or unscrupulous attorneys, notario fraud 2.0.

“That’s the new trend,” Curiel told me. “And it’s really hard to prosecute.” As a result of the crime, victims are often removed from the country, further insulating the perpetrator from consequences. “Just imagine what one’s family sacrifices in order to get the money to pay them,” a victim later told state investigators. “And they do not represent you.”

Alegal scam is a confidence game, and notario fraudsters often boast of their connections to the communities they exploit. Jessica grew up speaking Spanish with her father, who came to the United States from Mexico and became a citizen after marrying Jessica’s mother. They lived in Atascosa, Texas, a poor, unincorporated farming community southwest of San Antonio. Jessica married Eric Alva in 1998, when she was just eighteen. In the early years of their marriage, Jessica worked at a marketing agency and then as a Medicaid caseworker; Eric managed billings for a gastroenterology clinic. In 2006, he was accused of pocketing more than a thousand dollars in cash payments made by patients, but the charges were later dismissed.

In 2010, Eric and Jessica started working for Paul Esquivel, a prominent immigration attorney with offices in several cities across Texas. They helped prepare paperwork, answered the phones, and kept the office organized. “I just took it all in like a sponge,” Eric told me. “Jessica and I learned as much as we could.” In 2015, Esquivel was disbarred, and later he was fined $750,000 for running an asylum fraud scheme in which he fabricated stories of persecution so that his clients would be eligible for work visas.

At Esquivel’s office, the Alvas met a young lawyer named Katy Garcia, who had just graduated from the University of Texas Law School. Garcia remembers Jessica as friendly, talkative, and obsessed with designer shoes. “Every time I saw her, she was wearing high heels,” Garcia told me. “The really expensive kind.” Another former employer described Jessica as “highly confident” and also referred to her “expensive taste in fashion,” recalling that she and Eric never seemed to earn enough money to sustain the lifestyle they wanted. Eric was quiet, a broad-shouldered man with a well-trimmed goatee. “Jessica wears the pants in that relationship,” Garcia told me. “He will do whatever she says. If Jessica tells him to throw a cat from a balcony, he’ll do it.”

In the fall of 2011, Garcia decided to open her own practice. Six months later, Eric called to say that he and Jessica needed work. Garcia had only a few cases each month, so she couldn’t afford to pay the Alvas a salary. But Jessica and Eric said they didn’t mind. Looking back, Garcia admits that they “sweet-talked me and flattered my ego,” gushing about how excited they were to work for an honest and ethical attorney who was genuinely interested in helping immigrants. The Alvas agreed to take fees on a case-by-case basis, and pointed out that soon the business would grow and Garcia would be able to pay them more.

And grow it did. “Slowly, my name was getting out in the community,” Garcia told me. She was soon receiving multiple calls each week from friends and relatives of detainees. Because she spent most of her time at home or in court, Garcia would give the detainees’ information to Jessica, whose job was to meet them and relay to Garcia the facts of their cases.

The Alvas quickly realized that they could withhold information from Garcia and handle a lot of the work themselves. Garcia became suspicious after receiving a phone call from the relative of a detainee who said he had paid Jessica for legal services that never materialized. Not only were the Alvas pocketing money that should have gone to Garcia, they were also taking on new cases without informing her that those “clients” existed. “Nobody contacted me. No immigration official said, ‘Hey, we’re told that you’re representing this person, we have your forms here, with your signature,’ ” Garcia said. “Because I would have told them, ‘I have no knowledge of this immigrant, and they haven’t paid me a dime.’ ” (Eric maintains that he and Jessica always acted on Garcia’s behalf.)

Garcia cut off contact with the Alvas and reported them to the San Antonio Police Department, but because her business was based in Helotes, a northwestern suburb, she said they claimed not to have the authority to pursue the case. The murky and knotted levels of jurisdiction in which such crimes unfold make for difficult investigations. Take Duran: She was detained in the state of Louisiana, in the custody of the federal government, in a detention center operated by a private company. Her brother lived in Maryland. The Alvas were based in Texas. Where had the crime taken place?

Garcia started calling all the clients who might have been involved with the Alvas to let them know what was happening. To her surprise, some refused to believe it, and even accused Garcia of trying to pull a scam of her own. “Jessica’s just the perfect con artist,” Garcia told me. “She’ll find out what’s special to you, what interests you, and she’ll zero in and talk to you like you’re her best friend in the world. That’s what she did with these families. She’s very charming. They just fell in love with her.”

In early 2013, Garcia tipped off the Texas attorney general’s office, which began to build a case against the Alvas. Its Consumer Protection Division launched an undercover investigation and sent agents to pose as potential clients. By then, the Alvas had already filed paperwork to register their own business. They leased a small storefront in a strip mall in southwestern San Antonio. On the tinted glass door, they stuck a white decal depicting the scales of justice and a sign that read law office. For this new venture, the Alvas partnered with a lawyer named Jeffrey Garcia (no relation to Katy), whom Jessica had gotten to know while exchanging flirtatious messages on Twitter. Originally from San Antonio, Jeffrey had twice tried and failed to pass the bar exam in Texas, so he moved to New York, where he finally succeeded, and worked there for a number of years. (Because immigration statutes are federal, an attorney can practice immigration law anywhere as long as he holds a license in one state.)

The Alvas paid Jeffrey $1,500 every two weeks to be the “attorney of record” for their clients, neatly reversing the usual relationship between attorney and staff. The state would later allege that Jeffrey was their cover and a last resort should an actual attorney need to appear in court, but the Alvas did almost all the work and collected the payments. According to an office assistant named Seidy Lascon, Jessica would sometimes handle a case for weeks or months before Jeffrey was even informed of its existence. Lascon also said that, at least once, Eric impersonated Jeffrey on a telephone call with a federal judge. Speaking with the undercover investigator in September, Jeffrey referred to Jessica as “an attorney who became his mentor in immigration law.” When later asked why he would refer to Jessica in that way, since she did not have a law degree, he said it was “like a nickname.” In October, during a deposition conducted by state attorneys, Jeffrey estimated that he had around forty or fifty clients. When they asked whether he would be surprised to learn that he might have more than two hundred, he responded, “Little bit, yeah.” (Eric claims that he and Jessica never misrepresented themselves, but acknowledged that some clients might have been confused about their role. “We never tried to take advantage of anyone,” he said. “I couldn’t live with myself if we had.”)

When investigators from the Texas attorney general’s office deposed Jessica about her immigration business and precisely how Jeffrey fit into it, Jessica said that she and Eric enlisted Jeffrey because they thought he was a good lawyer. But Lascon, also deposed, contradicted that notion. She said the Alvas thought he was an idiot.

In April 2013, an asylum officer decided that Duran had established a “reasonable fear of persecution” in Guatemala, which allowed her to apply for protection and appear before a judge. After weeks of attempting to contact Jessica, Duran enlisted a fellow detainee who spoke some English to help her fill out the necessary paperwork. In careful block letters, the detainee wrote that Duran’s husband was violent, that just before she decided to leave Guatemala, he had cut the gas line running into her house in an attempt to kill her and the children. i have fear, the statement read. i am concerned of my safety my life. the safety and lives of my kids.

The evening before her court date, Duran was summoned by a guard to meet with her attorney. Expecting Jessica, Duran was stunned to see an unfamiliar man on the other side of the visitation booth: Jeffrey Garcia. He seemed panicked. According to Duran, he said that he had just become aware of her case that day, when an immigration judge told him about her upcoming court appearance.

Source photographs: © Spencer Platt/Getty Images; © Paul J. Richards/AFP/Getty Images

Typically, asylum applications require days, if not weeks, of preparation, but although Duran’s brother had been paying Jessica for months, it appeared from what Jeffrey said that nothing had been done to advance her case. The next day, Duran waited for someone to take her to the courthouse, but no one ever came, and she never saw Jeffrey again. She soon learned that he had withdrawn her application for asylum. In essence, she had requested her own deportation.

Duran began to warn other women to stay away from Jessica. But it was often too late. “So many got deported,” Duran told me. “They thought they were getting out. Nobody understood. In the end, after Jessica got the money, she would just say the person is requesting to end their case.”

Even in the rare instances when law enforcement has collected clear evidence of wrongdoing, scammers like the Alvas can evade real accountability. Because there is no federal statute that criminalizes notario fraud, many states rely on civil enforcement mechanisms meant to stop fraudulent business practices. These typically involve fines, but no jail time. Texas has been particularly aggressive about pursuing notario fraudsters in this way. In December 2013, after a months-long investigation spurred by the tip from Katy Garcia, the Texas attorney general filed suit against Jessica and Eric for violating the state’s Deceptive Trade Practices Act.

According to court documents, immigration filings, and my own interviews, the Alvas worked with six immigration lawyers over five years. Using doctored paperwork to gain access to detention facilities in at least four states, and sometimes impersonating their employers, Eric and Jessica met with hundreds of detainees, promising that the money procured from their families—hundreds of thousands of dollars in total—would pay attorneys who were working diligently on their cases. According to bank records subpoenaed by state investigators, they were at one point depositing as much as $80,000 per month into their bank account.

Jessica spent lavishly. Receipts appended to court documents show a charge on March 10, 2013, of $4,595 for Louis Vuitton “leather goods” and Prada handbags. Two months later, on May 23, Jessica spent almost $7,000 on handbags and shoes at Saks Fifth Avenue. The next day, she bought $625 pink Louboutin pumps with a three-inch heel. The summer before, Eric had sent a pair of $900 Louboutins to Jessica with the note, “For My Baby, Sorry it’s taken so long but I wanted to find you the right gift. I hope you like it. Love, Eric.”

The state’s case against the Alvas settled after a year. Although the couple was assessed $1 million in civil penalties, that amount was abated by 98.5 percent to just $15,000. Jeffrey Garcia’s penalties were abated by 86 percent. Katy Garcia was livid. “These two had no conscience. It wasn’t just one immigrant, or two, or three—they did it to hundreds. They made so much money, and just a slap on the wrist? You really think they’re going to stop?”

As part of the settlement, the Alvas were prohibited from providing services to anyone involved in an immigration matter; representing, directly or by implication, that they would procure such services; or accepting any money for doing so. They were also forbidden to enter any federal immigration detention facility for two years, though it was unclear how that would be enforced. ICE does not maintain a list of people barred from detention facilities as a result of state-level enforcement. Civil injunctions don’t even show up on the routine background check conducted before a visit. Moreover, the judgment included a mystifying provision, which stipulated that as long as the Alvas found a new attorney to employ them, none of the prohibitions applied at all.

The Alvas took advantage of this exemption and quickly found work in new law offices. But it didn’t take long for them to slip into familiar habits. By the summer of 2015, they had violated the terms of the judgment at least seventy-nine times.

In June, the state of Texas filed a motion to hold the Alvas in contempt, after discovering that they had committed, according to Valeria Sartorio, the lead prosecutor, “basically the exact same fraud they had been doing earlier.” They were accused of impersonating an attorney in court hearings, forging documents, and diverting client payments to themselves. The abatements were canceled, which meant the Alvas had to pay the full monetary penalty, and they were sentenced to eighteen months in county jail. They were released five months early, and very little of the money has been collected. Sartorio told me the state could potentially use the judgment to seize future assets, but at this point the Alvas have exhausted most of their funds. Many of the Alvas’ luxury purchases, including an emerald ring, diamond stud earrings, a green BMW, and a black 2006 Mitsubishi Galant, were seized and auctioned off by the state.

Notario schemes are typically treated as a type of small-claims consumer fraud, because the amount of money at stake in any individual case tends to be low, but I spoke to a dozen attorneys in several states who felt such penalties were not commensurate with the damage inflicted. When a mechanic upcharges you on a car repair, for example, you don’t get deported as a consequence. “It’s more than just economic harm,” said Curiel, the lawyer from San Antonio. “These scams devastate people and their families. The penalties are simply not harsh enough.”

As early as 2013, state lawyers had shared evidence from the case with several federal immigration agencies, but it can be difficult to persuade US attorneys to prosecute notario scammers at the federal level. Notario busts lack the career-making glitz of nailing smugglers or drug traffickers. It’s not until a scammer has been working successfully for a significant amount of time—often years—that the monetary losses are substantial enough to draw the attention of federal prosecutors. The Alvas had already been operating for three years when, finally, in the summer of 2015, the US Attorney for the Western District of Texas brought federal criminal charges against them, which included conspiracy to commit wire fraud and aggravated identity theft.

In March 2017, the couple took a plea deal for the conspiracy charge. They were fined $3,000 and given six months in federal prison. “So little,” Duran said when she learned of the sentence.

Late one afternoon last October, I met Jessica at Don Pedro’s, a family-style Tex-Mex restaurant on San Antonio’s south side. She had selected a location seemingly calculated in its wholesomeness. When I arrived, a mariachi band was playing under a faux-colonial archway, and a cluster of helium balloons hovered near the ceiling. Tables arranged into long rows bore plates of refried beans, small dishes of red and green salsas, and skillets sizzling with carne asada.

Jessica was seated in a booth toward the back. She wore a gold cardigan and a long necklace with glass beads. She was on the phone, and gestured for me to sit down as she wrapped up her call. “That was Eric,” she said solemnly. He was calling from prison. (The court had arranged for them to serve separate sentences so that one of them would be free to care for their teenaged daughter. Jessica’s sentence began in March; she is due to be released this month.)

I had been warned that Jessica would try to convince me that I was, as Katy Garcia had put it, “her best friend in the world.” Jessica laughed in deep, languorous bursts and pitched her body forward before speaking, to close the gap between her face and mine, as if everything were a secret. When she remembered an important fact, she snapped her fingers. She was by turns charming and evasive, treating me like a prospective client—“You’re a smart guy, I can tell that!”—then like a prosecutor deposing her—“No, sir, I never told them I was an attorney.” She swore that her days in immigration were behind her. After prison, she was thinking of opening a novelty shop that would sell anime comics and trinkets—anything that would allow her to own her own business. “I don’t work for anyone,” she said.

I asked whether she remembered Duran. Till then, she had made near-constant eye contact, but now she looked up, brow furrowed. “You know what, I really don’t,” she said. I felt a sharp jab on my left shin. Her face turned down with worry. “Oh, my gosh, I’m so sorry, did I just get you with my heel?”

Jessica told me she’d be available the following week to talk again. She shook my hand, smiling brightly, and said she hoped I would enjoy the rest of my stay in San Antonio. I tried to reach her several times after that, but she never returned my calls.

Duran remained in detention for almost three years. In March 2015, in exchange for her cooperation in the investigation against the Alvas, she was released under deferred action, a discretionary benefit that essentially pauses the government’s efforts to pursue deportation. As part of the deal, Duran was granted a work permit. Federal agents drove her to the airport in Alexandria, Louisiana, so she could join her brother in Maryland. “I cried and cried,” Duran told me. “One of the agents asked, ‘Why are you crying? You should be happy.’ I didn’t know why, but after so many years in that place, I just couldn’t stop.”

At LaSalle, Duran had earned four dollars a day preparing breakfast in the kitchen. In Maryland, she found a job cooking for a detention center, where she earned three times that in an hour. “When I’m cooking, I often relive my experience in Louisiana,” she told me. “Everything I cooked with there—the serving dishes, the platters, the utensils, even the can opener—is exactly the same.” Still, it was a good job, and she began to chip away at the debt to her brother, who had fronted money for Jessica and various other legal expenses during her detention.

After a year, however, her work permit expired. The government has the power to renew it, but the investigators involved in the Alvas’ case have stopped communicating with Duran. “If she gets picked up, she could be deported in two weeks,” Heather Benno, her current attorney, told me.

Benno believes that Duran should be eligible for a U visa, a special visa for individuals who assist law enforcement in an investigation or prosecution. Created as part of the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, which Congress passed in 2000, U visas are intended to protect victims of traditionally underreported crimes and encourage them to come forward. The visa provides a path to permanent legal residency.

To qualify, a victim must be “certified” by a law enforcement agency. Notario and legal services fraud are not included among the examples of “qualifying criminal activity” in the law, though advocates have argued that notario fraud often involves one of the crimes that do appear on the list, such as perjury. “When somebody works with law enforcement to prosecute a crime that involves lying to federal courts, that needs to be certifiable for a U visa, and that person should be protected,” Benno says. “There has to be a strong enough benefit associated for someone who is living in the shadows to feel like it’s in their interest to do so.”

Benno is mounting a new legal challenge to reopen Duran’s asylum case on the basis of a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. But Duran’s trust in the system has been deeply shaken. She has been robbed, passed from lawyer to lawyer, and persuaded to testify by state and federal investigators by whom she feels completely abandoned. “I’m a woman of faith,” she told me. “I try to remind myself that something good will come of this. . . . But sometimes I get very upset about everything that has happened.” Even if the case is reopened, Duran’s path to asylum has become much less clear. In June, Attorney General Jeff Sessions overturned the precedent that established survivors of domestic violence as a “particular social group,” writing that the category should not be “ ‘some omnibus catch-all’ for solving every ‘heart-rending situation.’ ”

For now, Duran maintains a simple routine. She works seven days a week. “It helps me, the work, staying busy,” she told me. She rents a small apartment and lives alone. Other than traveling to and from work, she tries to limit her time on the road, afraid of being stopped by police. “I know my circumstances,” she said. The evening is the highlight of her day, when her boys—now thirteen, fourteen, and twenty-one—call after school to give her updates about their lives, what they’re studying, what they plan to eat for dinner. “Always pizza,” she lamented. “I have to tell them, ‘No, you can’t eat like that all the time! You have to eat something healthier.’ ” But all she can do is tell them. The oldest has applied to study English on an exchange program in New York. If he is approved, Duran hopes to visit him there. It would be the first time she would see any of her children in person in more than six years.