Shota Rustaveli, Vephkhistqaosani (The Knight in Panther’s Skin) (ca. 1190)(K. Vivian transl. 1977)

On the rim of the Biblical world, in the mountains of Eastern Anatolia to the northwest of Mount Ararat, rises the river Kura. It winds its way into the Kartlian plateau becoming muddy and green, coursing past the ancient stone city of Mtskheta with its eleventh century cathedral, where the mighty river Aragvi increases its volume, then the hilltop monastery of Jvari with its crenelated roof, associated with the introduction of Christianity to the region in the fifth century. The river is framed by dramatically peaked hills covered in the early summer with lavender and wildflowers. It takes several wide bends before coming to the great Caucasus metropolis of Tbilisi with its curious architecture of overhanging upper floor verandas and its great fortress and then it turns to the south east past the city of Rustavi, once charming and rustic, now grim and industrial, before turning to the plain of Shirvan on its final sprint towards the Caspian Sea. It is one of the most hauntingly beautiful places on earth. It cast spells on a generation of Romantic poets—men like Mikhail Lermontov, who was so obsessed with the scenery that he took to painting it in landscapes to escape it. This is the land of Shota Rustaveli—whose name means “lord of Rustavi”—the great medieval poet of the Georgian language. They call him the Georgian national poet. But indeed, there is nothing particularly “national” about Rustaveli. He is more a poet on an endless journey, an inward-bound journey, whose writing points far beyond nations.

The first thing that is bound to strike his reader is that Rustaveli hardly seems constrained by such a narrow view of what constitutes “home.” Rustaveli is a writer of the twelfth century, of the Middle Ages. But his world covers a vast territory—from England to China. It’s hard to understand how a man of this period could have amassed such a prodigious knowledge of the earth, for surely this is not to be found among his contemporaries.

We know very little about Rustaveli’s life. He was orphaned at an early age, it is said. Was he raised in a Greek monastery in the Aegean, perhaps at Mount Athos? That’s possible. Georgia’s ties to Greece are profound (this is the land described in Jason and the Argonauts after all), and Georgian aristocrats in the Middle Ages liked to send their children to be educated and raised in monasteries in the Aegean islands. In any event, Rustaveli speaks Greek, quotes Plato and the Neo-Platonic philosophers at will (with and without attribution), and has an impressive command of the theology of the Greek Orthodox Church (though at times it’s something he very cleverly evades).

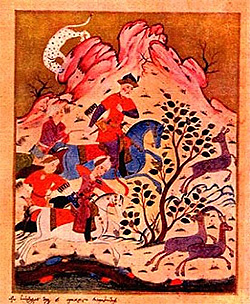

Was he a crusader? Georgia today is awash with the romantic imagery of the Crusades, and the nation has resurrected as its national banner the five-cross flag of St. George that Georgians carried into the Crusades. Rustaveli had a strong emotional connection to Jerusalem, where he went to spend his final years and died, at the Monastery of the Cross. He commissioned a series of frescos for the monastery, and one gives us our only contemporary glimpse of Rustaveli, from the years just before his death (it’s reproduced along side of today’s quote). His writings suggest he knew Jerusalem from an earlier period, and he would have been of military age in 1187 when Saladin (Salahuddin Al-Ayyubi) defeated Guy de Lusignan and captured Jerusalem – and indeed this is the approximate time of composition of his epic, The Knight in Panther’s Skin. In any event, Rustaveli knows Arabic, has a solid grounding in Arab literature, and presents the Arab warrior as a noble and romantic figure – the hero of his tale is in fact, not a Christian like Rustaveli, but an Arab knight and a Muslim.

He also knows Persian and Persian literature, which is not surprising for a Georgian noble. Throughout much of history, Georgia was in an existential struggle with Persian-speakers—and that threat lead Georgians around 1800 to accept the protective embrace of their Russian co-religionists.

Rustaveli seems to have a very deep understanding of, and respect for Islam. But it’s not just any Islam. It is specifically Sufi mysticism, and the book is filled with it. “Listen,” he intones more than once, the Sufi invocation. At the core of the story is a tale of unrequited love – at times it is the courtly love of the trouvères, but then many of the most majestic passages sound remarkably like Rumi and his talk of “the beloved.” He speaks many times of an ideal called “youth,” again a Sufi metaphor, and one leading to the central meaning of his story. So Rustaveli’s images are almost identical to Rumi’s. Did Rustaveli know Rumi? There is some overlap, though Rumi comes exactly one generation after Rustaveli. Never the less, Rustaveli is clearly well trained in the Sufi thinking and knows and uses the forms that Rumi mastered, and they are also geographically very proximate – the Seljuk realm that was Rumi’s home wrapped right around Rustaveli’s Georgia.

And beyond this, Rustaveli gives us some of the most remarkable accounts of the great oasis cultures of Central Asia that the Middle Ages produced. He talks about the commerce of the caravans that traversed the Silk Road, the “rubies of Badakhshan,” and the fabled production of cloth-of-gold that marked the high point of the civilization of Sogdiana (recently the subject of a magnificent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). Key scenes of his epic are played out in the khanate of Khwarezm, then rising to its historical apogee. And Rustaveli reaches beyond this world as well, to China and India, though his portraits of the Chinese and Indians are not enough to convince the reader that he’s actually been there.

To a Western reader these aspects of the Oriental world will perhaps not be so apparent as the tradition of the West that is repeated here. The Knight in Panther’s Skin was crafted more or less at the same time as the Nibelungenlied, as Tristan and Parzifal in the Germanic world; as the writings of Chétian de Troyes (especially Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to which it is bears some striking similarities) and the Roman de la Rose. Rustaveli manages the curious feat of spanning these traditions perfectly. Both scholars of the Christian epic of the Middle Ages and of Middle Eastern writing of the same epoch would see his work as being squarely in their traditions. How is this possible?

Rustaveli’s is the romance of the quest. It is not what one loves that matters so much as that one loves. It is not the object of the questing, but the quest. Rustaveli’s quest appears only on the surface to be a quest for a loved-one, or more specifically, inspired by a love one. His internal quest has an overpoweringly humanistic character to it. That is, a quest for the common ground between the warring cultures that existed all about him. Rustaveli’s adversary is intolerance, it is the tendency of man to look at another and see an enemy on account of differences in language, custom and confession, and not to see the same essential man.

He praises the gallantry of the chivalric tradition, he lauds feats of arms, but he condemns the needless slaughter because of difference. “Since God forgives our misdeeds, it is fitting for you, likewise, to show mercy to the vanquished.” (ch. 16)

Rustaveli’s knight does not demonize his adversary. Indeed, as in the story of Avtandil and Tariel which forms the work’s centrepiece, the man once an enemy, who sheds of the blood of friends and fellow soldiers, may soon be transformed into the closest friend –the “beloved.” This transformation comes through the recognition of the common objectives in quest. “A man who has lost heart can no longer act like a man—he is an outcast from humankind… He who does not seek a friend is his own enemy,” he writes (ch. 29).

For Rustaveli, the ultimate power of the quest is its ability to unite those who were once foes. “We are sworn brothers, he and I. He would give his life for me, and I am consumed with longing to devote myself to him. Devotion to a friend must know no bounds.” By contrast, in religion he sees both a fearsome power to unite and to divide. “God in Godhead, he in an instant can create unity from a hundred, but then also hundreds out of one.” (ch. 26).

Rustaveli’s technique is curious. Like a Russian matroshka he presents a seemingly endless sequence of tales within tales. At first glance they seem like a row of mirrors, each one reflecting its predecessor. Rustaveli tells a tale of a knight, who in turn tells tales of other knights, who in turn relates tales of their own chivalric exploits. In each an element of lost love appears. There seems a striking similarity in content in these tales. Yet they are different, reflecting different cultures, ages and faiths. In a sense, Rustaveli’s structure contains his message: that underneath superficial differences fundamental similarities are to be found.

Rustaveli was a warrior, and a poet, but also a man of state. He writes near the apogee of the medieval Georgian state, under Queen Tamar (the Georgians actually call her “King Tamar”) and the prologue contains a dedication to her and her consort. He held the office of state treasurer. Some of the most intriguing passages of the epic are of a political character. Consider, for instance, this charge delivered by a departing king to his designated successor, his daughter:

Be tireless in well-doing in great matters as in small, as the sun shines equally on roses and noxious weeds. Free men are bound by generous deeds, and those who are in bondage submit of their own free will. Let your beauty flow out like the tide of the sea, and like the tides return to you. Munificence is as fitting in a monarch as a tree in the Garden of Eden, and will turn even traitors into loyal subjects. We benefit from eating and drinking, not from hoarding up good things. What you give away remains your own, but what you keep is lost! (ch. 1)

Strange words for a minister of finance! And yet so typically Georgian. It helps one understand the country’s fiscal woes over the last decade—which are alas slowly being brought under the control of a very unforgiving tax regime.

And elsewhere he offers a series of curious prayers to the “seven stars” to enhance his abilities in governance: “He prayed to Mushtar (the planet Jupiter) supreme judge and arbitrator between heart and heart, not to be guilty of judging wrongly, and always to show mercy.” (ch. 32) Righteousness is the critical trait for a ruler, and justice is the essence of good government.

The message I see at the heart of this work is, however, one of a divine cord that unites humankind. It draws on the language of the Neoplatonic philosophers, but it also copies words of the Sufi poets, like Rumi, as they write of tauhid (“oneness”). It draws on the symbol common to Socrates and Rumi in making this point, namely, the sun:

“Oh Sun,” he prayed, “who have been called the image of a sunlit night, one in essence, timeless in the realm of time, whom the heavenly bodies obey to one iota of a second: do not change my fate, I entreat you, until she and I have come together again. Sun, whom the philosophers of old call the image of God, aid me who have become like a prisoner in chains!” (ch. 29).

“Sunlit night”? “Timeless in the realm of time”? What on earth does this mean? Over this chapter, he put as a motto: “The sage Dionysius revealed that which was hidden: that God made only what is Good, He creates nothing evil, but reduces ill to the duration of an instant and causes the good to endure, perfecting and not marring Himself.” This appears to come from the writings of the Pseudo-Dionysius now known as Areopagite. And it provides the key to understanding this most mysterious but critical passage. In “sunlit night” and “timeless time” we have the reconciliation of opposites which are critical to the Neoplatonic idea of the divine. But Rustaveli presents them also as a statement of what Rumi would call tauhid, the doctrine of oneness. He has found a point of confluence: between the philosophy of antiquity, adopted to Christianity, and Islam, as expressed by the Sufi mystics. A man overcomes the chains of perception only when he appreciates the hidden cord that unites men, one to his fellow man. The essential on which the focus must always remain is commonality, not distinctions. This is a path to inner and spiritual peace, but also peace among nations.

And understanding this, the curious conclusion of the epic also becomes clearer.

The three sovereigns did not forsake their friendship, but visited one another as often as they pleased. Gloriously they reigned, increasing their renown, suppressing insurrection and enlarging their domains. Their bounty like snow levelled inequalities, enriching the poor and bereaved so that none had need to beg. They were the bane of evildoers—not a lamb could steal another’s milk under their rule, and the wolf and goat would graze together. (ch. 52).

For Rustaveli and his religion-obsessed contemporaries, there would have been little hesitancy about what was intended with the selection of “three sovereigns”—this would immediately be understood as a reference to the three faiths “of the book,” namely Judaism, Christianity and Islam. The quest upon which Rustaveli embarked, the truth which his poetry seeks is the universal truth at the core of these religions. Rustaveli’s life was marked by the torment and horrors produced by faith-based conflict. His sweet vision is for reconciliation. It is a vision of no less power to us today than to Rustaveli’s time.